News

6 Things You Didn't Know About Torrey Pines

1. It is named for a rare pine tree.

The namesake Torrey Pine is a remnant of a prehistoric mountain range now submerged in the Pacific. The tree was discovered in 1850 by Dr. Charles Parry, who named it in honor of his mentor, Dr. John Torrey, a botanist from Columbia University. Unlike other white pine varieties, the Torrey grows in irregular fashion, with clusters of five pine needles that can reach nearly a foot in length. Its pulp is pliable, so the trees get gnarly and twisted in strong winds.

In all of North America, the tree is found only on the Torrey Pines mesa, locale of the 36 holes of Torrey Pines and adjacent Torrey Pines State Reserve, and on Santa Rosa Island south of Santa Barbara (the north end of the submerged range). It is against the law to cut one down. It can only be transplanted. So during the recent clean-up of the South Course, while hundreds of other trees were removed to open up vistas and improve turf conditions, 30 Torrey Pines were carefully relocated, and all survived.

2. The site was formerly an army camp.

In 1940, fearful of a Japanese invasion, the federal government leased 710 acres of the Torrey Pines mesa from the city of San Diego for $1 per year, as well as 500 adjacent acres from private landowners, to create an artillery training camp. Camp Callan opened in January 1941, 11 months before Pearl Harbor and the American entry into World War II. It became a city of 15,000, with paved streets and nearly 300 buildings, including three theaters and five chapels.

Less than three months after the Japanese surrender in August 1945, the camp was declared surplus and the lease terminated. The feds then sold all the buildings to San Diego for $200,000, a princely sum at the time.

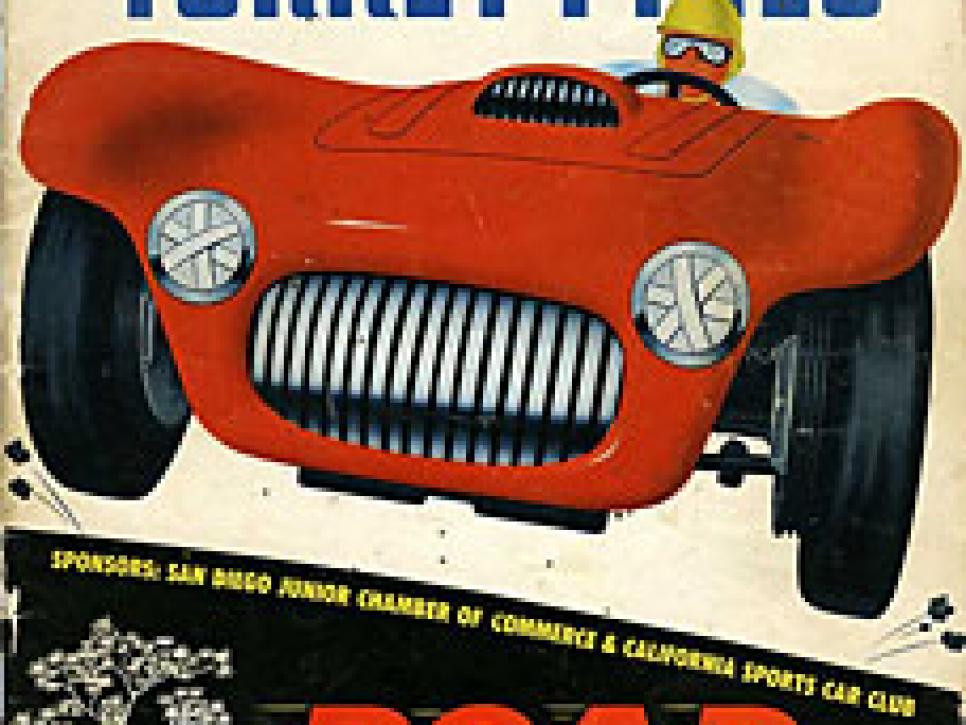

3. The site then became a race course.

After the buildings had been razed, the streets of Camp Callan remained, and with the use of some rubber cones and hay bales, it became the Torrey Pines Race Course in 1951, a twisting, turning 2.7 mile circuit on which both sports cars and grand-prix racers competed. There is nothing left of the race course today, but old-timers recall the start-finish line somewhere in the vicinity of the eighth green of the South course. Drivers headed north, turned left (across what is today the sixth fairway) on a loop that headed toward the ocean, then away from it (east on the first fairway of the North Course). Turning north again, the race track soon made two right turns to head south on a long "straightaway" (which had a couple of jogs in it) parallel to the Pacific Coast Highway (now Torrey Pines Boulevard). Today, that straightaway is occupied by a small practice range, parking lots, the Torrey Pines Lodge, a Hilton hotel and many office buildings. The final loop crossed somewhere along the ninth and 15th holes.

In 1955 it was decided to convert the raceway into 36 golf holes. Its last race was conducted in January 1956, an endurance contest of six hours, about the same amount of time needed for a weekend round at Torrey Pines these days. Some guy named Woods won the race. Pearce Woods, not Tiger.

4. The city credits the wrong guy with the course design.

Near the Torrey Pines golf shop, a series of plaques honors those responsible for present-day Torrey Pines. One gives credit to William P. Bell Son as original architects. That's wrong. The son, William F. Bell, designed the two courses. His father, William P. Bell, had been dead for four years at the time construction started.

Here's how the confusion occurred. In November 1950 the city of San Diego signed a contract with William P. Bell and Son, "a co-partnership," to submit a plan for an 18-hole golf course "suitable for construction on city-owned land in Torrey Pines mesa."

Through a series of delays (and his father's death in 1953), Willam F. Bell didn't receive approval for his final plan—which called for 36 holes, not 18—until 1955. Out of respect for his father, Bell had retained the company name. The city's contract was with "William F. Bell, golf course architect of Pasadena, Calif., doing business as William P. Bell and Son, Golf Course Architects." The plaque got the corporate name right, but not the actual guy.

5. In the beginning the courses weren't very good.

The Bell family dominated golf design in California between the 1920s and the 1950s. The father, William P. Bell, had worked with the legendary George C. Thomas Jr. on the the Riviera, Bel-Air and Los Angeles CC layouts.

Where his father dealt in quality, the son, William F., dealt in quantity. He mass-produced courses the way others churned out houses and automobiles, efficiently and inexpensively.

Apparently, before Bell started Torrey Pines, the city had the pavement bulldozed and buried, atop which he unwittingly built some tees and greens. Bell himself discovered this, but not until years later. Subsequent architects who have chopped into those greens have never hit concrete. But there are still piles of it out there somewhere. The unusual knob on the second hole of the South, short of the green, could well be concrete covered with turf. Beneath the South are also miles of sewer pipes. Rees Jones, in his 2001 remodeling, unearthed at least one manhole cover.

Bell's routing was suspect. The North had nines returning to the clubhouse, but the South did not. Some have questioned why he didn't finish both courses out on a cliff's edge, à la Pebble Beach. One can only conclude the city wanted the parking lot and clubhouse as close to the highway as possible. Critics have also questioned Bell's decision not to play holes over the deep canyons that cut through the site, or even play a hole or two down into and back out of one. That criticism is easy to rebut. The mesa was originally deeded to the city by the state, which retained ownership of all the canyons.

__ 6. The South got remodeled long before Rees Jones. __

The San Diego Open moved to Torrey Pines in 1968 and was renamed the Andy Williams San Diego Open. Golf Digest ranked it among America's 100 Most Testing Courses, but it really wasn't. It was windy and wet when the pros played there, so it played long, and its greens were impossible, sopping wet in front, rock hard on the back edges.

By 1973 the city realized it had to rebuild. Norrie West, who ran the Andy Williams event from 1969 to 1979, recalls that Jack Nicklaus, then a budding architect, was interviewed. "But Jack wanted to bulldoze the whole place and start over," Norrie says. "We turned him down.C

Instead, the contract went to local hero Billy Casper, who then had a design partnership with golf architect David Rainville. Rainville says it took them four years to rebuild all tees, bunkers and greens on the 36 holes.

"We'd start just after the tournament each year," he says. "We'd create temporary greens so they could keep running people through. Then we'd tear up one green per nine, get it rebuilt, get it back into play, then repeat the process."

Most of Rainville's reconstruction has since been swept away by the massive 2001 remodeling by Rees Jones. One major Rainville contribution that remains is the pond in front of the 18th green. PGA Tour officials suggested the hole needed beefing up, so Rainville dug the pond, using the dirt to create a new, elevated green.