News

Right At Home

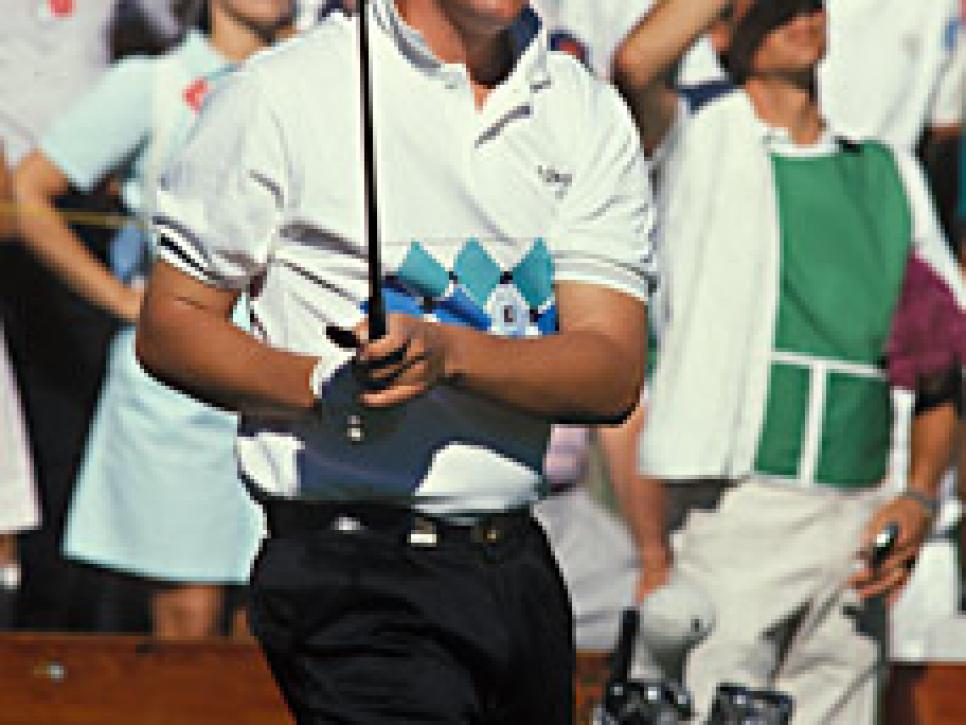

Boy wonder: Mickelson with the spoils from a 1980 San Diego junior event.

As Barbara Peters was saying, yes, it's quieter around the house now. Her children are grown, as have those of their longtime San Diego neighbors. But back in the day, there were times when the kid next door would try to circumvent the tangerine or lemon tree in his backyard and one of his practice swings went awry and an unguided missile didn't quite land softly, or upon yonder putting green.

"It's not like it happened often," she recalls, "but when it did, even if you didn't hear the crash, you saw the evidence on the floor of our den. A golf ball."

"Mrs. Peters would then phone and ask for my mother," confirms Phil Mickelson. "I would ask whether everything was OK, and Mrs. Peters would ask for my mother again. (Pause.) It seemed like it took me forever to pay for those windows."

Little did Barbara Peters, or her husband, Dr. John the obstetrician, realize then that the baby boy he delivered in 1970 would become rich and famous at this vocation. But Mickelson knew, probably even before he could verbalize his passion, and with the U.S. Open at Torrey Pines next week, the popular left-hander to whom every tournament seems like a home game can't wait for a chance, on his old stomping grounds, to seize his first national championship.

"I'm really excited to see it in Southern California," says Mickelson, "and I'm really glad that it will be on weekend prime-time television on the East Coast. It's scheduled to finish at 10 p.m. Sunday, right? That's great for the sport."

He doesn't miss much, in case you hadn't noticed. For a recent interview, this unthinking reporter showed up in a shirt bearing the logo from Winged Foot, 2006. "You had to have that on to talk to me, didn't you?" Mickleson jabbed playfully. "You didn't have anything else to wear? One of the biggest screw-ups in my career, and you've got to remind me." Mickelson is a different player now than then. Yet on the enthusiasm meter, he is only an adult version of the tyke who got hooked on golf before he could walk. "He's still Philip to me, because Phil is his dad," says mother Mary. "Anyway, late afternoon was fussy time for Philip when he was still crawling. So while I cooked dinner, Phil took Philip outside to keep an eye on him. Phil would putt or chip, and Philip would watch."

But not for long. Soon the son had to participate, and even after he was set-up by his right-handed father, Philip would swivel around to the left, completing the mirror image burnished in his fertile young mind. "Rather than change him because the mechanics of his swing were so sound," says Dad, "I took his club to my tool shop and turned it into a left-handed club."

I was no country club kid. We never lacked for anything, but it wasn't silver spoon, either.'

--Phil Mickelson

By 3½, Philip was too far gone. He begged in vain to join Dad at a real course, so Philip, not surprisingly, took matters into his own hands. "I packed my Flopsy stuffed animal and a bunch of balls into a suitcase, put my clubs over my shoulder and 'ran away' from home," he says. "I asked another neighbor directions to the first tee and she told me to take four lefts. That brought me back home, where my parents were waiting."

Impressed, dad brought his son to Balboa Park, where the starter reluctantly sanctioned an ecletic foursome that included Phil's grandfather on Mary's side, Al Santos. "Phil hit the ball, ran after it, and hit it again," says Dad. "He didn't slow up at all until the 18th hole, which he suddenly didn't want to play. I thought he was finally tired. No, the reason was Phil knew, if we played the 18th hole, it was over. No more golf for the day."

Phil the father eventually upgraded and that makeshift practice area became manicured with a bunker, shrubbery and assorted other hazards. Philip pounced on it, but the parents who at first slipped him a quarter for every chip-in had to lower the stakes to dimes, then nickels. By age 8, Philip took a job at Navajo Canyon, gathering range balls in exchange for playing privileges. Then, armed with his first set of real clubs -- a reward, after he won his first trophy -- Philip moved on to Stardust, where his Dad took out a membership. "I worked there, too," says Philip. "I was no country club kid. We never lacked for anything, but it wasn't silver spoon, either."

Indeed, Phil the son's forays into junior golf and his older sister Tina's gymnastics cost money. "We figured out Philip's trips one summer, and it came to maybe $5,000," says Mary, who took a job to make ends meet. Phil the father, who had to retire as a commercial airline pilot at 45 because of diabetes, was vested enough to secure non-revenue tickets for family members. "That helped," says Philip, "but I still got bumped when there were no seats, so I spent a few nights in airports. Memphis, Detroit, Minneapolis."

There was actually a dress code then, and when Philip arrived for one flight in Levis, he was rejected. "So," says Dad, "he traded pants with one of the employees. Phil's were way too large, but he's always thinking creatively, our son. On and off the course. Even when he had a girlfriend in high school, she was on the golf team."

Phil and Mary constantly fretted that Philip's obsession with golf would affect his studies. "Whenever I asked him about his homework, he would always say, 'Mom, I've got it under control,' " Mary remembers. "Knowing him, does that surprise you? But when we would go to a parent-teacher conference, expecting the worst, everything was fine. His grades were good." Even when Philip would be caught staring at a classroom floor, imagining how a ball might break across the linoleum.

On a family houseboat vacation, Philip took to hitting wiffle balls from the top of the boat into the water, to be retrieved by younger brother Tim, now the golf coach at the University of San Diego. At trip's end, Mary noticed gouges in the roof. "I said, 'We couldn't have done that, could we?' " Mary recalls. "Philip piped up and said, 'Oh, yeah, we could have.' " The boat owner repaired all divots with a fresh coat of paint.

Thanksgiving, 1985, was another matter. Informed that golf would give way to a family gathering that day, Philip dutifully resisted. "We weren't going to eat turkey in the morning," he reasoned. "So I called Chris Peters, our neighbor's son. I couldn't drive yet. He was older, so I paid him $5 to take me to Stardust. I didn't bother paying him for the return trip, because I knew I'd be covered, if you know what I mean. Well, I hooked up with some guys and played maybe three holes. Then I looked up and saw my parents. I shook hands with my group and wished them Happy Thankgiving. 'Time to go, fellas.' My parents were furious. But on the drive home, I remembered an old line from Ben Hogan. 'Every day I don't practice is another day longer before I become great,' I said. 'If you don't take me to the golf course, I'll just have to find another way.' Mom and Dad just looked at each other. They never said a word."

... Then, like now, he would try difficult shots rather than safety-first. Most of the time he pulled them off.'

--Dave Thoennes

No punishment ensued. Philip -- establishing a path he still pursues -- was not so afflicted by dimples on the brain that he was oblivious to other worldly endeavors. Unlike many teens, he never developed a taste for beer, but he socialized, although he missed his share of parties and dances. "Golf wasn't cool then," he says. "And golf fashion, you didn't dare wear to class what you wore to play. I wasn't a golf nerd, but I still did my thing. I could walk from school to work at the course. First tee time on weekends at Stardust was 6:50 a.m., so I had to be off no later than 6:45." At Mary's behest he took a music appreciation course. He memorized composers by golf clubs. "A strong, bold symphony was a driver," she says, laughing. "Something lighter and softer was a 9-iron."

Philip also dived into other sports. "He did everything well," says Paul Hubka, then the athletic director at Blessed Sacrament grammar school. Hubka now is a San Diego police officer who walked inside the ropes during last January's Buick Invitational at Torrey Pines, where the left-hander referred to him as "Coach." Baseball, football, volleyball and basketball occupied Philip when he wasn't submerged in golf. "I even played soccer," he says. "Didn't run very fast -- I know that amazes you -- but I could kick, which I also did in football, along with being quarterback. Right-handed, like everything else. Broke my arm. That's this scar here."

When Mickelson graduated to University of San Diego High, a Catholic school of about 1,200 students, he was an instant linchpin on Dave Thoennes' golf team. "I was there for 33 years," says Thoennes, 70, now retired. "But he knew more about the game and what the ball did than I ever knew. Phil was obviously gifted physically, but he had the mental side of the game down, too, which is unusual for that age."

The "Uni" squad played nine-hole matches at Torrey Pines, and when the opponent was an inner-city school with competitors who weren't quite steeped in technique, Philip would pause while playing to give adversaries lessons. "But when we were up against our bigger rivals," Thoennes recalls, "Phil didn't offer any help. He concentrated on winning, which he did almost all the time."

During a practice round Mickelson notched a double eagle on a par 5 -- "The only one I've seen to this day," says Thoennes. Another time, a foe shot even par and Mickelson crushed him by eight strokes with a 28. "Phil was our No. 1 guy for three of four years, just a shade ahead of Manny Zerman," says Thoennes. "Phil didn't really need a coach. He was a leader and even then, like now, he would try difficult shots rather than safety-first. Most of the time, he pulled them off. I didn't think it was my job to restrain him, because he was so talented, and so confident."

Thoennes also taught a typing class, and Philip was conscientious there, too, not that he considered sportswriting as a backup plan. There was no backup plan for this young man, although he did stray every once in a while.

When Mickelson secured his driver's license and his first car, he and Zerman -- whom Mickelson would defeat in the 1990 U.S. Amateur final -- decided to explore nearby Tijuana, Mexico. Unfortunately, Mickelson's Kharman Ghia got swiped by another driver, and there went midnight curfew. "All Philip had to do was call us," says Mary. "But he didn't. And he wasn't supposed to go to Tijuana, either. At midnight my husband locked the door to our house. Philip had a key, but Phil put the chain up too. I could see Philip through the peep-hole, just sitting on the front step, and I wanted to at least give him a blanket. But Phil said no, this is going to be a lesson for our son. So Philip slept there all night. We were probably stricter than we had to be because there just weren't many times when Philip did wrong. But we can look back at it now and laugh."

The Mickelsons do a lot of that now because they always have. Phil and Mary encouraged a fun-first objective for their son's golf, and he embraced the game accordingly, with a caveat from above. "We knew Phil had a special gift," says his dad. "But we always wondered, what will happen when he gets older and meets up with other people with special gifts? That's why we always stressed education and why we always held it over him that if he didn't do his chores, we would take his clubs away."

Philip listened. "Because of my parents," he says, "I learned that golf was a reward, a privilege, not a requirement or something I was entitled to."

Mary remembers a day when Philip played with a gentleman who had just graduated from a top university. "He told Philip he would be a top player who would make a lot of money someday," she says. "And in order to manage it and do what's right for his career, he had to go to college. If we had concerns about Philip turning pro after high school, they ended. Philip came home that day and told us, 'I'm going to college.' "

When Philip won the 1991 Northern Telecom Open on the PGA Tour while a junior at Arizona State, his parents braced themselves. "I had [super agent] Mark McCormack right here on my couch," says the father. "He couldn't talk to our son because [Phil] would have forfeited his eligibility. McCormack talked about how Phil's marketability would never be greater and so on. I told McCormack I thought any corporation would be more impressed by a young man who finished what he started, college, than by a young man who won a golf tournament. I didn't want to speak for my son, but that's the way [Philip] felt too, and it seems to have worked out."

Attention, attention, all ships at sea. Beware of unidentified flying objects. After this U.S. Open the entire Mickelson family is planning another houseboat vacation.