News

Drivable Par 4s

Seductive yet substantial, Riviera's 10th offers many options and might be the tour's best short par 4.

Locked in a compelling Presidents Cup duel last fall with Canada's Mike Weir, Tiger Woods stepped onto Royal Montreal's 14th tee with the honor. Having whittled an early three-hole deficit in their Sunday singles match to one, Woods faced the water-guarded green just 292 yards away from a tee constructed especially for the event with exactly this scenario in mind: creating uncertainty in the minds of the world's best golfers.

"He's tempted!" NBC's Johnny Miller practically shouted into his microphone, gleeful to witness a rare moment of indecision from one of the game's most strategically resolute players.

Woods laid up and won the hole with a hard-fought par, while Weir made a clumsy bogey after laying up. Although the hole already had secured its place in golfing infamy the day before when Woody Austin attempted to drive the green and splashed his way into 200,000 YouTube replays, the actions of Woods and Weir on the hole were indicative of a more noticeable and dramatic trend in competitive golf: the drivable par 4 and the challenges -- both physical and psychological -- it presents to the world's best players.

In an age of 350-yard drives that reduces the number of "do-I-go-for-it?" decisions on par-5 holes, the drivable par 4 has become the place where serious golf fans -- whether from behind the gallery ropes or from their living-room couches -- delight in the spectacle of watching the game's best weigh the pros and cons of a tantalizing shot as they also recall past performances and consider their place on the leader board.

"It's pretty simple in terms of what makes the best short par 4s so great," says Davis Love III. "You have to make a decision instead of just banging it out there. [Those situations] are just exciting to watch." The appeal of drivable par 4s on the PGA Tour can be credited as much to TV executives (who love the drama of scenarios such as the Woods-Weir dilemma) as it is to course architects and tournament setup officials. The increase in interest of this type of hole has been so meteoric that they are now an expected twist in almost every tournament course, both for entertainment and examination purposes.

"In this day and age of guys bombing it so far, the short par 4 offers the ultimate defense of getting the big hitter in trouble if he happens to not drive it well," says NBC announcer Dan Hicks. "And if you can bring more middle-of-the-pack guys into a short par 4, where they have to make the same decision as a guy like Vijay or Tiger, it makes it that much better to watch."

Thanks to a 20-yard driving distance increase on the PGA Tour since the late 1990s, more short par 4s are within reach of the world's best while decision-inducing par 5s are practically obsolete. Diminutive two-shotters -- any par 4 less than, say, 350 yards -- often are the only holes in tournament golf offering a perfect blend of options, including the most tantalizing choice of all: a chance to drive the green and register a round-altering eagle.

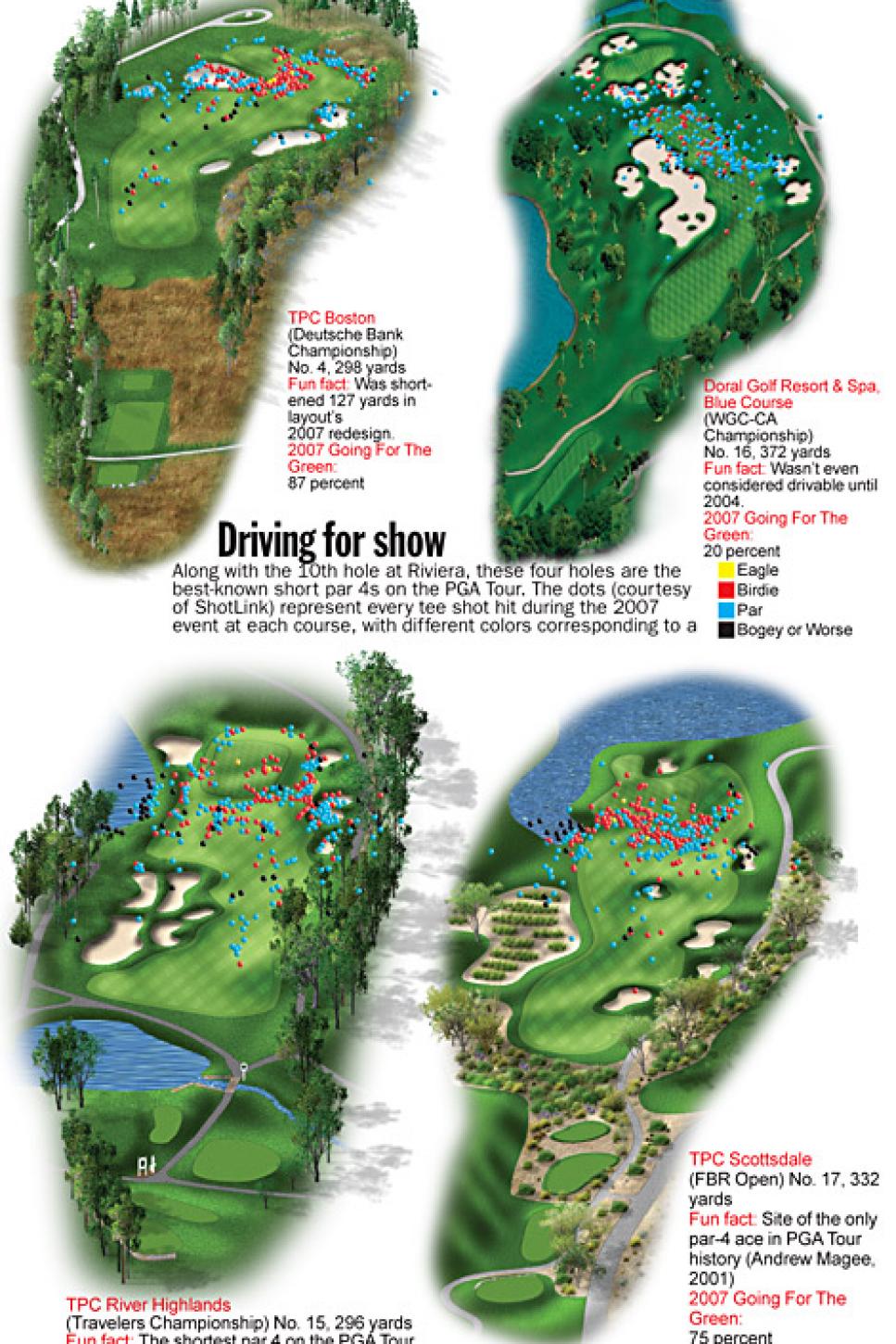

Short par 4s have long been part of the golf architect's palette, from the earliest links courses to the noted finishing holes at long-time major championship sites Olympic Club and Inverness. But few competitors -- if any -- try to hit those greens from the tee. Starting in the early 1990s, golf fans and players discovered a renewed appreciation for par 4s that were legitimately drivable -- with Riviera CC's historic 315-yard 10th (see page 26) and the TPC Scottsdale's wily 332-yard 17th the best-known examples.

But the actual birth of the current drivable par-4 movement probably took place at The Belfry, the much-maligned Sutton, England, layout that hosted four Ryder Cups from 1985 to 2002. The 10th hole at The Belfry is a short par 4 with a tiny, banana-shaped putting surface wrapped around some trees set just beyond a small creek. For the first three Ryder Cups played there (1985, '89 and '93), European captains Tony Jacklin and Bernard Gallacher set the tees so the hole measured 287 yards -- short enough that players on both teams could attempt to drive the green, provided they wanted to risk tangling with tree branches and a water hazard.

The strategy worked brilliantly. The Belfry's 10th emerged as a fan favorite on an otherwise forgettable modern design as tormented Ryder Cuppers agonized over the decision to lay up with as little as a 7-iron or go for the green with their drivers or 3-woods. Matters were made even more dynamic by the crowd's influence.

"When a player would reach to pull out his driver, the fans would cheer. When he reached for an iron, they'd all boo," recalls NBC golf producer Tommy Roy. "It made for great drama."

(When the Ryder Cup returned to The Belfry in 2002, European captain Sam Torrance, trying to play to his shorter-hitting team's strength, stretched the 10th hole to 311 yards and shifted the tee-shot angle to make going for the green less tempting. It was an unpopular decision among fans and even the players themselves. "It was the perfect match-play hole," Woods lamented. "You could make 2 or you could make 6. That's what made it so much fun.")

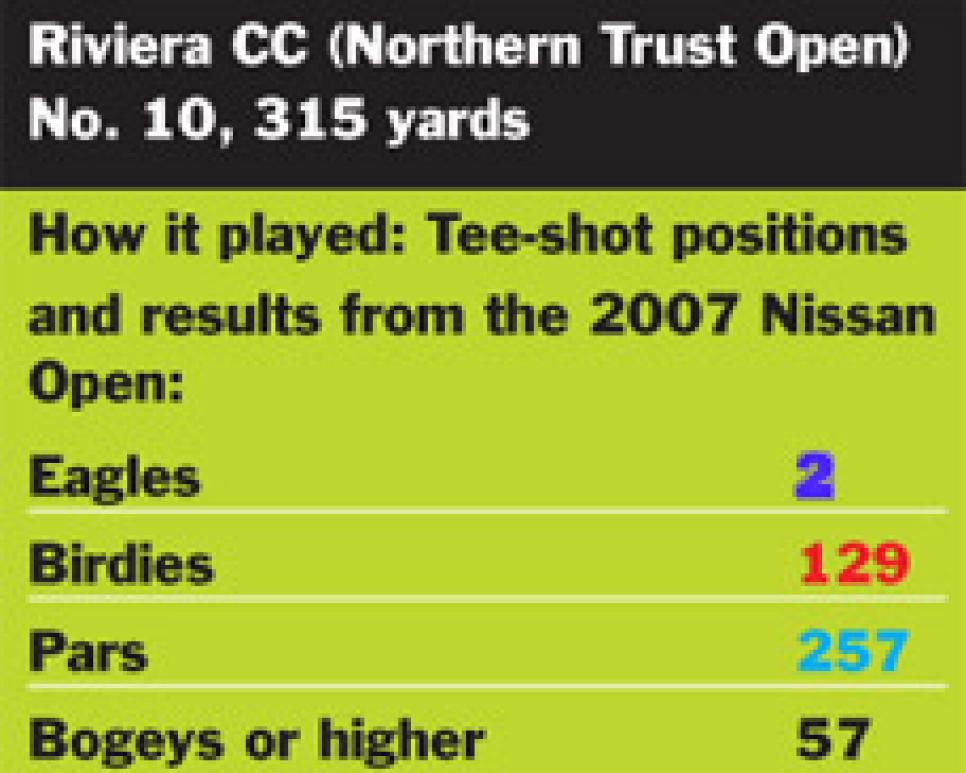

While The Belfry's 10th is considered among the first of the modern era's drivable par 4s, many players consider Riviera's 10th -- which will confound PGA Tour veterans once again at this month's Northern Trust Open -- the best. "It's such a supreme example of a short par 4," says Geoff Ogilvy. "It really doesn't have many peers."

Playing from a slightly elevated tee to a massive fairway, the tee shot offers several options: Lay up left, for the ideal angle into the bowling-pin-shaped green protected by deep bunkers. Or lay up right, leaving a shorter pitch but from a tougher angle, with the green at its shallowest and sloping away from the direction of the approach.

Or the third option: Take your driver and go for the green.

"When a short par 4 is done properly, it favors no one, and No. 10 at Riviera is the poster child for short par 4s," Arron Oberholser says. "A long hitter can hit driver, but if you miss it an ounce right, you're dead. And if you lay up left, you have to lay up just far enough so that you're hitting straight into the throat of a tiny green. It's a 300-yard hole that plays like a 450-yard hole."

The best quality about Riviera's 10th, says Ogilvy, is it is so seductive. "You know if you lay up all four days you will have a great chance of beating the guys you are playing with," says Ogilvy. "Yet even though you are aware of that, sometimes you still can't lay up. [And] when you don't go for it, and the two guys you're playing with do go for it, you walk down the fairway wondering, 'Why did I lay up?' Whichever play you choose, you can also be just as easily annoyed at it. That's the measure of a great short par-4: how uncomfortable it makes you on the tee."

The drivable par 4 era isn't just a result of golf architecture, but of the boom in power. Advances in technology and equipment have allowed PGA Tour players to take cracks at greens they couldn't reach 20 years ago, such as Doral's 372-yard dogleg 16th, where Phil Mickelson and Tiger Woods put on a heroic display during the 2005 Ford Championship.

The number of holes shorter than 350 yards on PGA Tour courses actually has dropped in recent years, from a high of 41 in 1994 to 32 in 2007. However, on the short holes the players face, they are choosing to hit their drivers more often. In 2002, the first year the PGA Tour's ShotLink database tallied its "Going for the Green" stat, 43 percent of tee shots attacked short par-4 greens. By 2007 that number had increased to 50 percent.

A further look at the stats suggests the evolving strategy is the right one -- more players are succeeding at conquering the short par 4s than ever. In 2002 players who tried to attack those holes from the tee were a cumulative 718 under par; those who laid up were just 145 under. Last year the difference was even more pronounced: 1,415 under to 241 under, in favor of the gamblers.

Even major championships are getting into the drivable par-4 act. Augusta National famously shifted its third tee forward during the final round of the 2003 Masters, inducing a shocking double bogey from Tiger Woods, who was in contention. The PGA of America and the USGA also have started to maximize the potential of drivable two-shotters during their major championships.

The 2006 U.S. Open featured a drivable par 4 on the front nine (Winged Foot's 321-yard sixth hole), and the outcome of last year's national championship was influenced greatly by Oakmont's 313-yard, par-4 17th. USGA set-up man Mike Davis is said to be already lamenting that this year's U.S. Open host, Torrey Pines, lacks a classic reachable par 4.

His counterpart at the PGA of America, Kerry Haigh, has been utilizing the short par-4 option as far back as 1995 (Riviera's 10th). Haigh requested a special tee be built for the sixth hole at Oakland Hills (356 yards), which he used to torment players in the 2004 Ryder Cup (that tee survived Rees Jones' recent redesign, so watch for its use at August's PGA Championship). Haigh also is eyeing Valhalla's unforgettable 13th -- a downhill 352-yarder to a green built on a rocky island in the middle of a creek -- as a possible 2008 Ryder Cup equivalent to The Belfry's 10th. (He has the blessing of American captain Paul Azinger, who still doesn't expect many players to take a shot at the green.)

"From the 17th at Oakmont to the sixth at Winged Foot to the 16th at Doral, they're all so different and each has its nuances," says Hicks. "I still don't think there are enough of them. Every good golf course should have one sprinkled in there because it's such a great departure."

RIVIERA'S 10th: NOT ALWAYS PERFECT

Revered for creating Riviera CC's 10th hole, the golf architecture duo of George Thomas and Billy Bell actually envisioned a slightly different hole when the course opened in June 1927.

The original design featured a crowned, bunkerless green that amateur greats Bobby Jones and Charlie Seaver were able to drive in Riviera's pre-Kikuyu grass days. Prior to the 1929 Los Angeles Open at Riviera, Thomas outlined the addition of four bunkers carefully installed under Bell's supervision: a new far-left bunker that players still try to lay up short of to secure the best approach angle and three small greenside bunkers guarding the middle and rear hole locations.

The new hazards immediately established the 315-yard hole's ingenious demands. A golfer who overcomes the instinctive desire to play straight toward the hole, and instead takes the slightly longer route to the left still consistently secures the best approach angle. Riviera's 10th also disproves the theory that to be interesting, a hole must be narrow and feature dramatic elevation change or even extravagant natural hazards. Sure, the fairway bunkers are impressive in scale, but the hole drops just 15 feet from tee to green and the largest fairway bunker is not in play for most golfers.

Over the years, encroaching Kikuyu and exploding bunker sand reduced the size of the putting surface and deepened the greenside bunkers. In 1993 Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, as part of their redesign of the course, went to work on the 10th. Working with superintendent Jim McPhilomy and Riviera's then-director of golf, Peter Oosterhuis, the group restored the fairway to its original width, which returned the "sucker" option of laying up down the right side. Also restored was a tight grass chipping area that collected most approach shots that rolled off the putting surface.

Prior to the 2007 Nissan Open, architect Tom Marzolf added new bays (the peninsulas of grass weaving in and out of the sand) to the large fairway bunker, shifted the left lay-up bunker a few yards and eliminated the greenside chipping area Coore and Crenshaw had restored. The result was a 20-percent increase in players going for the green with their tee shots.

On top of its many fascinating design elements, Geoff Ogilvy suggests that No. 10's place in the round adds to the its brilliance.

"The eighth and ninth holes are very hard, but you know that the 10th and 11th [a reachable par 5] offer a couple of birdie or even eagle chances. So it sits in the round at the perfect time," says Ogilvy. "It's definitely a much better hole than it [would be] if you teed off there to start your round when the dynamics just aren't nearly the same."