News

Iron Man

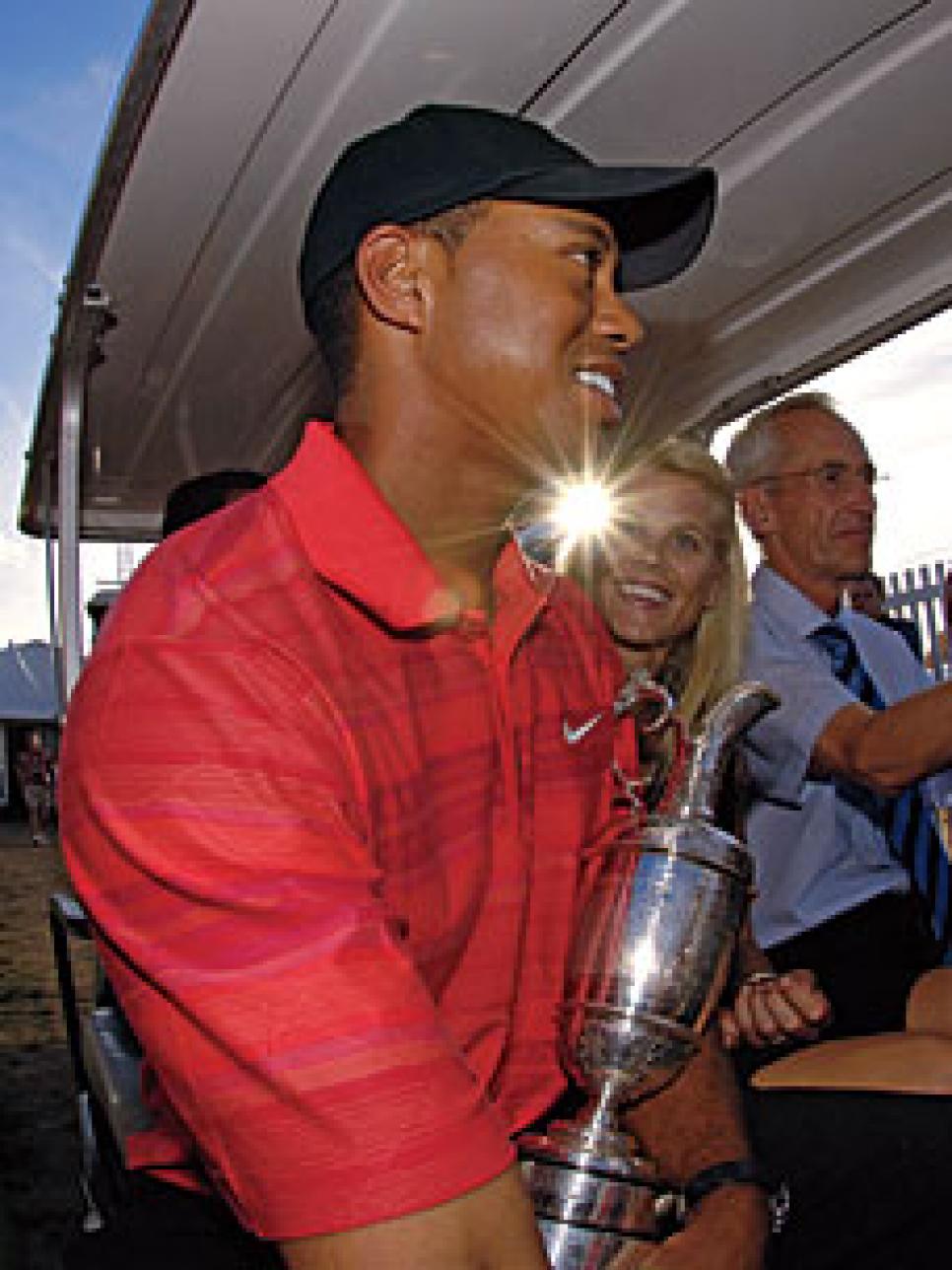

Done deal: In charge after 54 holes, Woods locked up his 11th major title with an air-tight, closing 67.

Think of his 11th major title as an amalgam of qualities borrowed from the third, fourth and seventh of those triumphs, which isn't to say Tiger Woods is running out of fresh ideas. The near-flawless iron play bore a (ball) striking resemblance to that mind-blowing performance at the 2000 U.S. Open. A week in Great Britain without visiting a fairway pot bunker? It's just a slightly modified sequel to the sand-free safari at St. Andrews one month after he had pulverized Pebble Beach.

As for Woods' ability to drop an anvil on the hopes of every big-name contender on a star-stacked leader board, one might refer to the 2002 Masters, when five of the game's top seven players turned what should have been a memorable Sunday afternoon into an audition for the role of Wile E. Coyote in the old "Road Runner" cartoons. Tiger's success in protecting 54-hole leads—he is 11-0—is nothing short of amazing. So is his habit of turning formidable foes into hapless cartoon characters.

For all the recurring themes and busted dreams, however, the 135th British Open forged more than enough of its own identity to avoid classification as a cheap imitation. Let's start right where it ended: Woods sobbing uncontrollably in the arms of his caddie, Steve Williams, the stream of tears merging sadness and joy like few moments in golf history. More than our first look at the game's coldest-blooded competitor surrendering to such emotional vulnerability, what made Tiger's weeping so powerful was the swiftness in which it happened.

Not five seconds after tapping in for par and a two-stroke victory over Chris DiMarco last Sunday evening at Royal Liverpool, Woods would have melted on the 18th green's dead grass had Williams loosened his grasp. Their hug seemed to last forever, which wasn't long enough. From there, Woods moved directly to his wife, Elin, and an entire universe of golf fans witnessed another unedited scene of reality TV. For one unforgettable minute, the world's best golfer—maybe the best ever to walk the earth—was just a boy who wanted his daddy.

You didn't get that at the '02 Masters.

So Woods is back, forever at a loss since the May 3 death of his father, Earl, forever a champion after this latest how-to-win clinic. "I wish he could have seen it one more time," Tiger said of the man who articulated his vision in myths and made his son a legend. "I was pretty bummed out after not winning the Masters because I knew it was the last major he was ever going to see. That one hurt a little bit."

A little history never hurt anyone. Woods' third claret jug tied him with Walter Hagen for second place in career professional major victories, a feat that may take a while to sink in. He became the first player to win back-to-back British Opens since Tom Watson (1982-83), took the lead on the PGA Tour's 2006 money list, and officially rinsed away the aftertaste of that missed cut at last month's U.S. Open.

What shouldn't get lost in all the bookkeeping is that Woods led the field last week in driving accuracy, which is like Fred Flintstone winning an Oscar for Best Actor. Tiger missed just eight of 56 fairways. Of course, he used his driver just once in 72 holes—on the par-5 16th in the first round—which only prompted the game's political extremists to decry the notion that someone could shoot 18 under par at a major championship without the aid of the club that usually accounts for about 60 percent of a venue's overall length.

It's a foolhardy rant. Woods is influential, but he didn't petition Mother Nature for an unusually dry month leading into this tournament, nor did he advise architect Donald Steel on where to reposition the bunkers in the "modernization" of Royal Liverpool that led to its hosting this Open. Besides, Tiger wasn't the first to try it (see Jack Nicklaus, 1966 British Open, or Seve Ballesteros and others, 1983 U.S. Open), just the first to do so and dominate in the process. "I have never seen anyone, even him, strike long irons the way he did this week," Williams marveled. "It was unbelievable. It was like he walked his ball out to the yellow dot [a fairway yardage marker] and just dropped it there."

Employing a consistent diet of 3-woods and 2-irons off the tee, Woods basically forced himself to play an 8,000-yard golf course. He didn't set foot in any of Royal Liverpool's fairway landmines because he didn't hit enough club to reach them (Tiger did play from three greenside bunkers). The strategy left him with more 180- to 225-yard approaches than he has had at a tournament since the age of 5, but Tiger hit 58 of 72 greens in regulation, more than anyone but Michael Campbell (59).

Swing coach Hank Haney scoffed at the idea that Woods was afraid to hit his driver because he rarely knows where it's going. "He drove it better at the Western Open than he has in five years," Haney said of Tiger's last start before the British. "The long [second] shots don't bother him, [and] most guys can't hit their 2-iron as far as he does. He ends up with a 4- or 5-iron [approach]. The shorter hitters are looking at a 3-wood from the same spot. They have no choice but to take on the bunkers [off the tee]."

For the record, One-Driver Tiger played Royal Liverpool's par 5s in 14 under. Among his most notable pursuers, Chris DiMarco was nine under on the same holes. Sergio Garcia checked in at eight under, Ernie Els at 10 under. If those numbers don't silence the fanatics, nothing will. "He had a game plan and stuck to it," Els said. "At times I didn't think it was the right plan because he's so long off the tee—he could be hitting very short irons into some of the holes. But he stuck to his plan and it worked out for him."

Els sighed. Some stuff does get old. "You know, he knows how to win these things," he added. "It's going to be tough to beat him now."

Not that it ever wasn't. Losing to Woods means different things to different people, depending on how many major trophies you have in your living room, where you start play on Sunday, and at what point you lose sight of the guy in the red shirt. Let's start with the good news: DiMarco did more than anyone to infuse the final round with some competitive electricity. As Woods neared completion of a ridiculously efficient front nine, stretching his one-stroke lead to three and looking like he would win by six, DiMarco took it upon himself to offer some resistance.

Paired with Els in the group just ahead of Woods and Garcia, the 2005 Presidents Cup hero rolled in an 18-footer for birdie at the 13th just as Tiger was missing his first fairway of the day on No. 11. Woods saved par there, but he missed the 12th green left, chipped to 15 feet and two-putted for bogey. His advantage was down to one, which might not have meant as much if DiMarco hadn't holed a 60-footer for par at No. 14, then knocked his tee shot to 12 feet at the par-3 15th.

Ladies and gentlemen, today's rout is officially canceled. "Whatever I did, I couldn't drop [another] shot and give Chris any more momentum," said Woods, who was fully aware of DiMarco's charge. But just as quickly as things got tight, Tiger regained control. DiMarco missed the 12-footer. Woods lasered his 191-yard approach at the 14th to eight feet, converted the birdie attempt, then went pin-hunting again. His tee shot at the 15th left him seven feet. It might as well have been seven inches.

After three three-putts (34 putts overall) and a third-round 71 to match the score of final-group partner Els—Garcia shot a 65 to earn the pairing/death sentence alongside Woods on Sunday—Tiger rolled his ball extraordinarily well on his last lap around Royal Liverpool. "Sometimes his shoulders get a little open [aiming left]," Haney explained. "I saw it before he teed off Saturday and kicked myself because I didn't say anything. Sometimes Tiger takes the advice, sometimes he doesn't, but then he goes out and three-putts three times. I was pretty annoyed with myself."

Long before the back-to-back birdie conversions that put his third jug on ice, Woods avoided trouble early with several outstanding long putts. Every 40- to 60-footer stopped within four feet of the hole, leading to stress-free pars that had everything to do with his jarring a 25-footer for eagle at the par-5 fifth. Tiger's speed was exceptional, which takes us to Garcia, which takes us to the bad news. As has been the case several times in recent years, Sergio crippled his elusive chase of a major title with an ultra-tentative stroke, the most notable example having occurred while paired with Woods in the final round of the 2002 U.S. Open.

This time, Garcia flinched over a five-footer for par at the second after his drive left him 112 yards in. He then flubbed a 3½–footer for par at the third. When Sergio's drive at No. 5 suffered a head-on collision with the eight-foot wall flanking the back end of the left fairway bunker, he was as done as done gets. "One of these days, everything is going to go my way and nobody is going to touch me," he said, seemingly allergic to the theory that champions make their own breaks and losers dwell on them. "I can't even count how many good putts I hit that didn't go in."

Alas, there is some good news. Sergio will live to play another day. "I can only control myself," he added. "I'm not going to kill myself over this."

The same could be assumed of Els, who opened with rounds of 68-65, then stumbled to a pair of 71s on the weekend. This was another opportunity lost, no doubt about it, but Els' slow return to form after knee surgery last summer cast this solo-third finish in a positive light (see sidebar).

Both Els and Jim Furyk (solo fourth) began the day in excellent position—Els trailed Woods by one, Furyk by two—then removed themselves from serious contention early. For Furyk, it was a bogey-bogey start. Els, meanwhile, birdied just one of the first 13 holes and drifted backwards after holding a share of the lead on the sixth tee. At the par-5 10th, Els dumped a 6-iron into the right bunker, hit a great recovery, then struck an unsightly push from five feet that cost him a must-have birdie.

We keep waiting for guys like Els and Garcia to step up, hunt down Tiger on the back nine of a major, then redefine their careers with some clutch play down the stretch. Whether both men suffer from an accumulation of competitive baggage is something best discussed around the water cooler, but as the years go by and Woods continues to execute at a level that seems to drive his quasi-rivals into submission, it's getting tougher and tougher to argue against the premise.

Sergio started making putts as soon as he had fallen far enough behind Woods to not feel any pressure. Els' first birdie of the back nine didn't arrive until the 14th, by which time only DiMarco had a realistic chance. "Chris birdied and Tiger bogeyed, and it was down to one shot," Furyk said. "And the next thing you know, Tiger birdies the next three holes. If you put a little heat on him, he goes and makes three straight birdies. That's tough."

That's the point—it's always Tiger and only Tiger who seems to rise to the occasion. As tenacious as DiMarco is, he doesn't have the talent of Els or Garcia. So we keep waiting. And waiting. "It's so hard to win these things," Haney offered. "You think about how well Tiger played. He missed three shots all week. He holed a 4-iron for eagle [Friday at the 14th] and made a 60-footer for birdie [eighth hole, same day]. He putted beautifully on three of the four days, broke par in every round and still only won by two."

In retrospect, it does seem like such a small margin of victory for such an airtight performance, especially against the backdrop of a final round in which so many of the usual suspects could be found in all the usual places. When Woods arrived here to begin preparation of his title defense, it took him no more than two holes in his first practice round to realize that hitting his driver would produce too much risk and not enough reward.

Royal Liverpool? Talk about oxymorons. The old English mutt better known as Hoylake was browner than a Texas muny, dehydrated by a dusty summer and as linksy as a links course gets. Its broad fairways were yielding outrageous roll, its burned-out rough not presenting much of a deterrent, its greens no quicker than medium-fast, at least until the weekend. And everybody loved the place—it was as if Hoylake's 39-year absence from the British Open rota only made hearts grow fonder.

By week's end, after a major-championship record number of players (67) broke par in the first round, after the one-under cut marked the first time since 1990 a player had to shoot in red numbers to qualify for the weekend, after three days of abnormally high temperatures and not enough breeze to scare anyone, the world's best player won somewhat comfortably with a strategy so conservative no one else seriously considered it.

Maybe that should tell us something. Shoot, if Tiger Woods had hit his driver, he might have won by eight. That would have made his 11th major title look more like the first, third and fourth … but honestly, don't they all seem to follow a certain pattern?