News

The Magic Kingdom

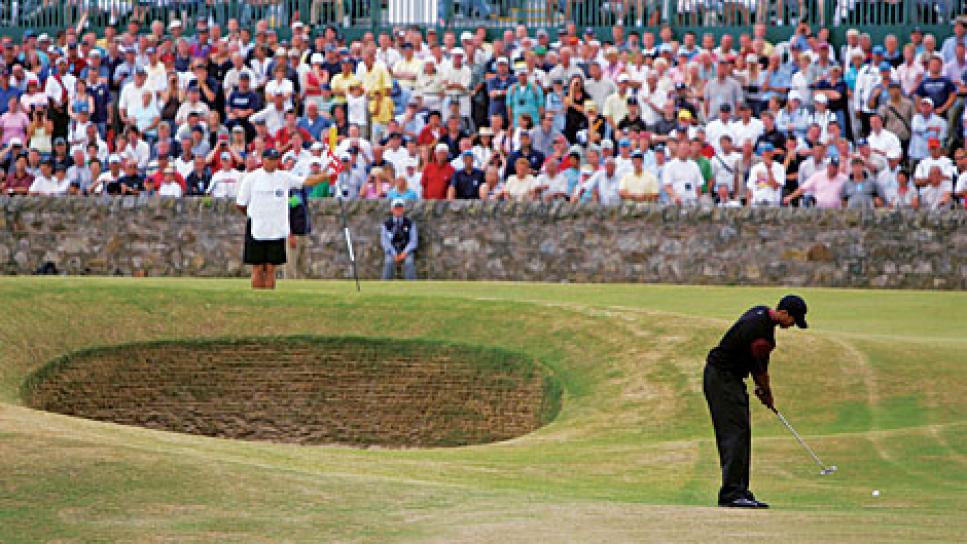

The Old Course, ringed by the white path, stood up to new demands.

Two hours after Tiger Woods had putted out at the Old Course, people wandered contentedly about the first and 18th fairways, making practice swings, running with their children, taking in how the green expanse is so wondrously framed by an extended wall of craggy architecture. Cooled by the calmest of zephyrs amid the gentle light, they seemed in silent agreement that somehow the ground they stood on was magical.

That St. Andrews, in its 27th hosting of the oldest major championship, would once again emerge as not only the most romantic but arguably the most competitively compelling venue in the game was, frankly, amazing. This was to be the year that would finally prove the Old Course was too old for big-time golf. Apparently marginalized at the 2000 championship, where Woods achieved a record score of 19-under 269 with hardly an uncomfortable moment, the old girl was teed up to get bombed back into the bygone age of balata.

"To be honest, I had a bit of that fear," RA chief executive Peter Dawson confided after the championship. "I did expect the record to be challenged or broken."

The litany had been building since the completion of last year's championship at Royal Troon: The players are too strong, the driver heads too big, the ball far too hot, the links ground too firm. A longer-than-ever Woods, not to mention Ernie Els, Vijay Singh and Phil Mickelson, would reduce the Old Course to a pitch-and-putt. The only defense would be a high wind and, perhaps, unavoidably silly conditions reminiscent of another course that proved too short for the modern game, Shinnecock Hills. Everyone silently braced for a royal and ancient embarrassment.

Well, the wind didn't really blow—at least never more than 20 miles per hour—and the RA, to its credit, didn't go off the deep end on its setup. And yet the Old Course not only held its own, it produced yet another classic championship.

Let's count the ways. As has happened at St. Andrews too often to be an accident, the best player in the world won. Indeed, the last seven times the Open has been held at the Old Course, the winners have been Jack Nicklaus, Nicklaus again, Seve Ballesteros, Nick Faldo, John Daly, Woods and Woods again. Throw in predecessors that include Bobby Jones, Sam Snead, Peter Thomson and Bobby Locke, and you have the greatest list of champions any course has ever produced.

The leader board was similarly representative. Among those finishing in the top 15, nine were former major champions, seven of them at least twice. "She separates the wheat from the chaff," said Thomson, who won there in 1955. "If you play well, you will be rewarded. If you don't, it slaughters you. It's the best course that has ever been."

Even in relatively benign conditions, no new milestones were set. David Frost tied the 18-hole championship course record of 65, but even as 59 of the 80 finishers were under or at par, there were only 16 scores better than 68 all week. And only one player, Woods, finished double figures under par. How did it happen?

First, give the RA credit. The 164 yards of added length—bringing the total to 7,279 yards, the par remaining at 72—was intelligently applied. The stated purpose—to put the course's 112 bunkers more into play—was achieved. According to the British and International Golf Greenkeepers Association, the field found more than a third as many bunkers as it did in 2000. Woods, who famously missed them all in 2000, hit into four.

By all accounts, the RA's excesses were relatively few. There was some noise about the tee on the 480-yard fourth hole being pushed so far back that some players couldn't reach the fairway, but it was muted. Fred Couples called the new tees "fantastic." And a mistake was made by placing deep hay to the right of the 17th fairway. It was the first time long grass had been grown in an area that had always been the reward for the aggressive, hotel-hugging line off the tee. RA chief Dawson later conceded that the extra growth was "probably not the smartest thing," but fortunately it did not play havoc with any of the contenders. In the end the 17th, always the hardest hole at St. Andrews, actually played easier than it had in 2000, with a 4.63 average compared to 4.71.

Meanwhile, the course's four drivable par fours, Nos. 9, 10, 12 and 18, weren't substantially changed. With the wind down or usually favoring, they were driven more than ever, often with 3-woods. But as short par 4s have become accepted as some of the most exciting holes in big-time golf, rather than being dismissed as Mickey Mouse, the length and daring of the shots brought an element of excitement to the championship. As Dawson pointed out, the holes are "separators" where more talented players can apply their skill to gain a tangible advantage.

While no one would argue that a steady diet of such holes would be appropriate at most courses, their preservation at St. Andrews fits the timeless nature of the venue. For that matter, the two par 5s, the 568-yard fifth and 618-yard 14th, were regularly hit in two with irons—also mostly because of downwind conditions. Saturday, the shortish-hitting Brad Faxon drove three par 4s and hit both par 5s in two. "That doesn't happen to Brad Faxon too often," he said.

Statistically, the Old Course got taken apart. Woods led the driving stats with an average of 341.5 yards, while the field average was 312.7; in fact, only three players among the 80 finishers averaged less than 300 yards. The field hit 74.1 greens in regulation, a figure which would lead that category on the PGA Tour most years. Scottish amateur Eric Ramsey, used to the links bounce, missed only 10 greens all week.

But where St. Andrews gives, it also takes away, and in a way that makes it more resistant than other courses to the effects of technology. As a counterbalance to the length the ball traveled, the hole locations became the course's best defense. The Old Course's immense greens provide myriad possibilities, and in conditions Nicklaus described as "bouncy" even for links golf, pins were placed where no conventional approach could get within 20 feet. But perhaps conditioned by the experiences of Shinnecock Hills and—most recently—Pinehurst, there were almost no complaints. "The RA did a great job with the pin positions and the way they set up the course," said Sergio Garcia, who finished T-5. "They should be proud of it."

More than ever at St. Andrews, solid putting from distance and sure holing became the order of the day. Although the greens never got quicker than 10.6 on the Stimpmeter (while the ninth and 10th fairways were measured at 11), the championship was in many ways a marathon putting contest. Woods tied for the fewest putts with 120, a figure which would never lead at any other major venue, while the field average was 129, which would have been dead last at the U.S. Open.

What is almost unquantifiable—at least until ShotLink makes its way to Fife—is the confounding nature of a St. Andrews eight-footer. Between wind, grass irregularities and the subtle breaks, the feeling over these crucial putts is often one of uncertainty. For all his wonderful ball-striking, it was Woods' will and focus within this zone that was the biggest contributor to his winning. If he had putted nearly as well last month at Pinehurst as he did last week on the Old Course, he would be going for the Grand Slam at Baltusrol.

"This week the great putters are shining," said Tom Watson, who finished a credible T-41 while ranking 56th in putting. "When you play St. Andrews and there is not a lot of wind, that putter is the one stick that is going to win you the golf tournament."

Making the big putts is in concert with the other great challenge at St. Andrews, the weight of history. Bobby Jones' statement that no career is complete without a victory at St. Andrews always weighed on Nicklaus' mind, and even Woods seemed more inward and tense than usual. "It's the greatest stage in golf, the major of majors, and we all know that," said Ian Baker-Finch, who led after three rounds in 1984 at St. Andrews. "Everyone wants it too much and tries too hard. The great champions find a way to get it done under the great pressure." Last week, of the 18 players who started the final round within six shots of Woods, only one, Bernhard Langer with a 71, broke par.

No wonder it has so often taken a big player, physically and mentally, to win there. Langer, who tied for fifth, knows how often physical power can sometimes negate the otherwise capriciously firm conditions, and he saw it again in Woods.

"The course suits the long hitter and probably somebody who spins the ball a lot, too," said Langer, whose Sunday run was undone when he chili-dipped a short pitch into a pot bunker on the 15th. "Tiger has the option to stop the ball extremely quick, which you need on some of these greens which slope away from you and the wind going with you. I think it's his short game that is the major key. He putts very well, chips well, has good imagination. It's the right combination around here."

But St. Andrews runs too fast and is too fraught with danger to simply be overpowered. Brawn has to be tempered with brain in terms of judgment, nerve and improvisation. Because each shot along the bouncy hollows is unique, no one gets dialed in at the Old Course. "So many intricacies, you never really understand it," said Baker-Finch. "It demands art, not science." And to Thomson's mind, it's the reason the course so consistently identifies greatness. "Every [golfer] who has ever won at St. Andrews has been a good thinker," he said. "That's all I ever really had as a player. Tiger in particular is a wonderful thinker. He just has a brilliant golfing brain."

Of course, St. Andrews has the ultimate advantage in getting the benefit of the doubt. Sure it's awkward, bouncy and blind, but the quirkiness is somehow endearing. We will forgive it almost anything, because after all it is the original course. The sheer fun of it, and why it's so many players' favorite, is that it just is. "Any course I've played in my life, I've never hit it over a building," said Kenny Perry. "But it's OK." Or as Woods himself said after playing St. Andrews for the first time 1995, "I thought it was the coolest place on earth."

And judging by 2005, a place that will hold more magical Opens.