News

Knockout Punch

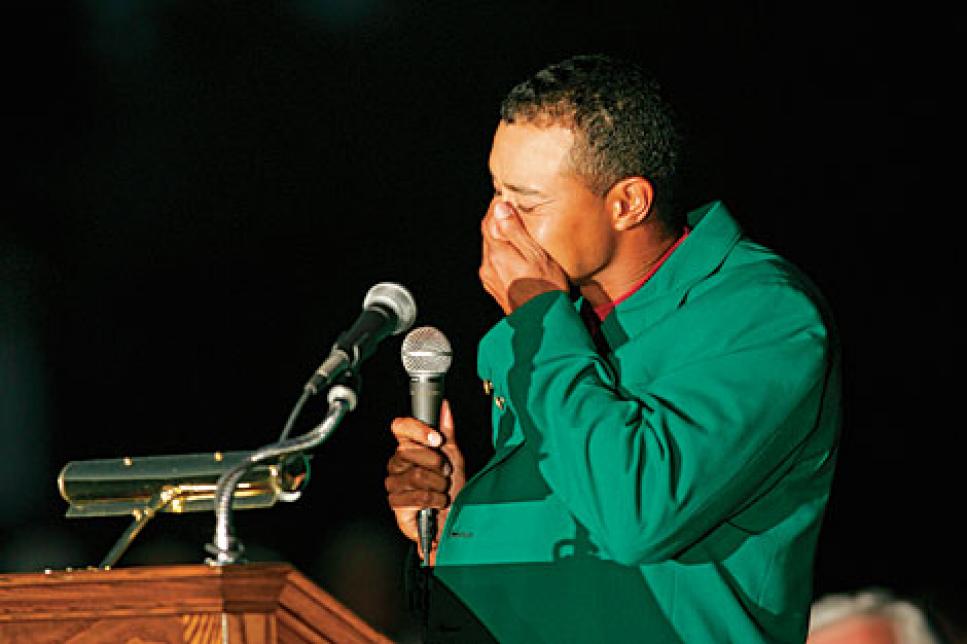

Showstopper: Woods capped Sunday's drama with a 15-foot birdie in the playoff.

The cakewalk days are long gone, the double-digit victories a memory as distant as those ridiculous gaps between first and second place. His dominance now comes and goes: seven consecutive birdies here, an all-over-the-ballpark 74 there. And nobody drops three strokes during the first-tee handshake anymore. Not to a guy who had picked up his last major title 34 months ago, a guy whose pursuit of immortality no longer qualifies as a mere formality.

Even in victory last Sunday evening, Tiger Woods looked vulnerable. Back-to-back bogeys on the final two holes of regulation, one of the greatest shots in Masters history nullified by a blast 30 yards right of the 17th fairway, to which swing coach Hank Haney shrieked, "We're going to fix that friggin' driver." His lead down to one on the 18th, Woods' famous door-slamming skills were compromised in uncharacteristic fashion by a push-sliced 8-iron approach, leaving him with a bunker shot you couldn't get close with a large bucket of balls and a month's worth of lessons from Dave Pelz.

Perhaps this green jacket should include an elbow patch on each sleeve. And a reversible bib. "Interesting finish," Tiger called it. "Even though I was throwing up on myself the last couple of holes, I sneaked one out."

Not before losing at least one finger in a mighty battle with the grinding Gator better known as Chris DiMarco, which is to say Woods didn't claim his fourth Masters triumph and ninth major crown a moment too soon. A 15-foot birdie putt on the first extra hole—the same 18th he had bogeyed 20 minutes earlier—earned the greatest player of this generation a two-month pardon from the oversize expectations that have dogged him the better part of three years. As if he needs it, Tiger's third win of the year made him another $1.26 million, which loosely translates into two Buick commercials and one American Express spot.

More importantly, it bought Woods some valuable real estate—a perch exactly halfway up Mount Nicklaus, which stands 18 professional majors high (see page 49) and has proven particularly treacherous since Tiger's win at the 2002 U.S. Open. Asked last Sunday if Jack's 1995 prediction that he would eventually win 10 or 12 Masters provided any incentive for the only long-term goal that matters, Woods suggested such lofty praise makes for better comedy than motivation. "Just wondering what he was smoking," Tiger cracked when reminded of the comment.

It's easy to joke around when you begin Masters Sunday trailing by four strokes with 27 holes to play, wipe out the entire deficit by 9 a.m., build your own four-shot cushion, then spend every penny of it before reminding everybody about your allergy to losing. Without question, Woods played some of the best golf of his career in the second and third rounds of this Masters—a dazzling 15 under par in a 30-hole stretch, with many of the birdies coming on putts your Sunday partner could have made.

As brilliant as DiMarco was for the first 21/2 rounds, darkness fell Saturday night with the wrong guy in his rearview mirror. "A bogey and a birdie is two shots," he pointed out after touring the back nine in 41 strokes on an otherwise gorgeous Sunday morning. "I certainly wasn't trying to [be cautious]. I was trying to make birdies and extend [my lead]."

Whatever DiMarco did, it didn't work. He resumed his third round on the 10th tee and promptly rifled his approach into a bush right of the green. Double bogey. One group ahead, meanwhile, Woods picked up right where he had left off, adding four consecutive birdies to the three he had made the previous evening, matching Steve Pate's tournament record, which occurred in 1999 on the same seven-hole stretch (Nos. 7 through 13). When Woods safely reached the 14th green in a swell of a.m. sunlight, he was nine under for the round, scaring every flag and looking a lot like a guy who might turn Augusta National's 18-hole scoring mark (63) into a Sunday morning cartoon.

Without any forewarning, Tiger three-putted the 14th, then plugged his 6-iron approach in the hill of the hazard fronting the 15th green. He would sign for a 65. It's worth noting that Woods shot the lowest score in the field in two of four rounds but still needed extra holes to get out alive. If nothing else, DiMarco's tenacity matched Tiger's inconsistency.

So it obviously wasn't pretty. Not that it has to be. "He didn't miss a shot left all week," said Haney, whose watery eyes reflected the satisfaction of a man who has been maligned simply for working with Woods. Reminded of the drop-kick hook Tiger managed to move 100 yards off the second tee Friday morning, Haney pointed out that Woods began the hole like a 22-handicap but finished it with a par. "When I really wanted to see his best swing, which was in the playoff, that's what he had," Haney added. "Both of them."

In the final analysis, that is what decided the 69th Masters. For all the ugly shots Woods has hit since dominating golf from late 1999 through the middle of '02, this was by far the clearest validation of the work he has put in with Haney—not just physically, but in terms of swing philosophy. He proved to himself that the changes will work under extreme pressure, however flawed they were at the end of regulation, and that his ability to turn into Superman with the game on the line is still what separates him from everyone else.

He is the best player in the world. Even at 80 percent.

Returning to the 18th tee for the playoff (previous sudden-death playoffs started on the 10th hole, but in 2004, Masters officials switched to the 18th hole, because of issues involving sunlight and crowd control), Woods ripped a 3-wood down the middle and found himself with another 8-iron in, only this time from the fairway instead of the left rough. "Two of the best golf shots all week," he said of the combo, which left him directly above the front-left pin with a putt similar to the one Phil Mickelson holed to win last year's Masters.

As he had done to force sudden death, DiMarco saved par with a superb chip from the run-off area short of the green. All day long Woods had smelled blood, only to stop and sniff the azaleas. With the sun sinking fast and perhaps allowing for just one more hole of daylight, with DiMarco behaving like a dog that could chew on Tiger's leg well into next week, Woods put an end to a tournament drenched in trauma and drama.

"He's a fighter, a wonderful competitor," the champ said of DiMarco. "He drives the ball extremely straight, and you know he's going to be in your face all day." Not for nothing, DiMarco shook off that horrid back nine Sunday morning to fire a closing 68, which would have been absolutely spectacular if he had trailed Woods by fewer than three after the third round.

DiMarco's solid finale was even more impressive when you consider he had to deal with a broken driver on the eighth hole—a point in the tournament when he still was three behind Woods. After hitting his tee ball, DiMarco noticed the epoxy that holds the head and shaft together had come loose, twisting the head. Under the rules, he was allowed to replace the disabled club.

"Thankfully I had another one with me," said DiMarco, who normally travels with just one driver. "I put the one I was using in on Wednesday and I had four or five others in my locker. They brought [the backup] to me on the ninth tee so I didn't miss a drive."

Not since Tom Watson (1978 PGA Championship and 1979 Masters) has anybody—not even Greg Norman—lost playoffs in back-to-back majors. "I went home and changed shirts because the other one was no good," DiMarco said, explaining his Sunday afternoon revival. "I went back to the black shoes instead of the white and tan, changed my belt, changed my socks, and I was like, 'OK, new start. That's over with. Let's go back.'

"I went out and shot 68, and 12 under is usually good enough to win," DiMarco said. "I was just playing against Tiger Woods."

Tiger is Tiger because he does stuff like chip in for birdie at the par-3 16th, which is fast becoming golf's official home for miracle shots, unforgettable putts and the occasional hole-in-one. Woods added his special touch in the twilight, clinging to a one-stroke lead but in serious danger after DiMarco parked his tee shot 14 feet below the flag. Woods pulled out his 8-iron and flew it over the green. When he arrived at his ball, he found himself with a mysterious 10-yard play from where the tightly mowed apron meets the rough.

Davis Love III had holed out from a similar spot on the 16th six years earlier, but not with the game on the line. "It's one of the best shots I've ever hit because of the turning point involved," Woods said. "If Chris makes his putt and I make bogey, all of a sudden I'm one back. I remember Davis chipping in from over there, but I wasn't necessarily thinking about making it. I just wanted to throw the ball up on the [slope], have it feed down there, and hopefully get a makable putt."

Woods picked out a spot maybe 20 feet left of the pin and nailed it. His ball did as it had been told, even sliding left toward the hole after moving right most of the way. It stopped on the edge of the cup, thought about going in, then gave Nike about three seconds of free advertising before disappearing. Even in the Tiger Woods School of Suspense, this was as good as it gets.

Elin Nordegren, known since last October as Mrs. Woods, leapt into the arms of Tiger's agent, Mark Steinberg. Haney, a man who doesn't get worked up unless the subject is fellow swing coach Jim McLean, began celebrating like a schoolboy. DiMarco missed his birdie try, and Tiger was back up by two, seemingly capable of playing the final holes with a pool cue and still finishing the job.

There was just one problem: Nobody told DiMarco to roll over. He made a five-foot comebacker for par at the 17th after Woods bogeyed. And he hit a good chunk of the cup on his first chip at the 18th, saving par again from five feet. "This would hurt if I gave it away, but I didn't," DiMarco said. "I really didn't. I played him as hard as I could down the stretch, birdieing a bunch of holes and putting it on him, really. If I'd gone out and shot 41 on the back nine [Sunday] afternoon, I would be very disappointed, but I put that behind me."

The victory celebration in the Woods' camp was as emotional as any other in his professional career. Woods and his caddie, Steve Williams, shared at least three exuberant bear hugs before Tiger exited the 18th green. Behind the scoring hut, he was embraced by his mother, Kultida; his wife, who bestowed a rare (for this couple, anyway) public kiss on her husband's lips; Steinberg; and Nike official Greg Nared. Throughout, the happiness on Woods' face was as genuine as Tim Herron's at Thanksgiving dinner.

At the awards ceremony, Tiger was more somber—probably at the sense of relief that came with the end of his 10-major drought, certainly at the absence from the tournament grounds of his father, Earl. The elder Woods was in Augusta last week, but so weakened by chemotherapy treatments for cancer he had to remain at the family's rented home throughout the week. At the podium, his fourth green jacket hanging loosely on his slumped shoulders, Tiger tearfully thanked his father. When the champion returned to the house later, his last and most meaningful hug of the night went to Earl, who told the group, "We may have seen the awakening of a sleeping giant. We caught a glimpse of what his swing can be, and it's awesome."

In 20 years or so, we'll have a better idea whether this Masters marked not only the awakening of a sleeping giant, but the final appearance of a revered one, Nicklaus. After rounds of 77-76 left him five strokes beyond the cut, Jack really, really sounded semi-certain this would be his last competitive appearance at Augusta National, saying, "This is not a celebrity walkaround. This is a golf tournament, a major championship, and if you're going to play in this championship, you should be competitive."

It's all relative, Jack. Nobody came close to keeping up with Woods and DiMarco. Not former No. 1 Vijay Singh, who hit a tournament-high 58 greens in regulation but needed 129 putts—more than anyone who made the cut. Not defending champ Phil Mickelson, who hung around into Sunday morning but missed a pair of eagle putts inside 10 feet near the end of his third round—opportunities he couldn't afford to squander.

Not the rain, which delayed the start of the 69th Masters by 51/2 hours, then limited play to less than three hours Friday. Nor tournament official Will Nicholson, who seemed to be the only one who didn't know that it was Phil Mickelson's spike marks Vijay Singh complained about during the second round (see page 44). Not even the confusion at the start of Saturday afternoon's third round, when a computer crash forced officials to work out pairings and starting times by hand. A bit rusty at the process, organizers made mistakes, leading to players starting off the wrong tee, with the wrong playing companion, at the wrong time—as if those who barely survived the cut had been instructed to simply make their own game on the putting green and head out.

"Kind of like back in high school," one veteran smirked.

Not that anybody will remember that. Woods' ninth major title began as an exercise in futility. Other than the putt he rolled into Rae's Creek at the 13th, the flagstick that spat his ball back into the bunker at No. 1, the tree he hit on No. 8, the rules infraction somebody called in on him at the 14th—Woods was quickly cleared on charges that he stood directly astride his ball on a tap-in—and the tough-toenails break on the par-3 sixth, where his ball landed six feet from the hole, rolled down the slope and eventually required Woods make a 15-footer to save bogey, his first round went exactly as planned.

Oh, well. All's well that ends well. "I've won seven majors with my other swing, now this one with a different swing the first time around," the winner said. "So it did all right."

Indeed, Tiger, but that's eight majors with the old swing and one with the new swing. Not that anybody's counting.