News

No Laughing Matter

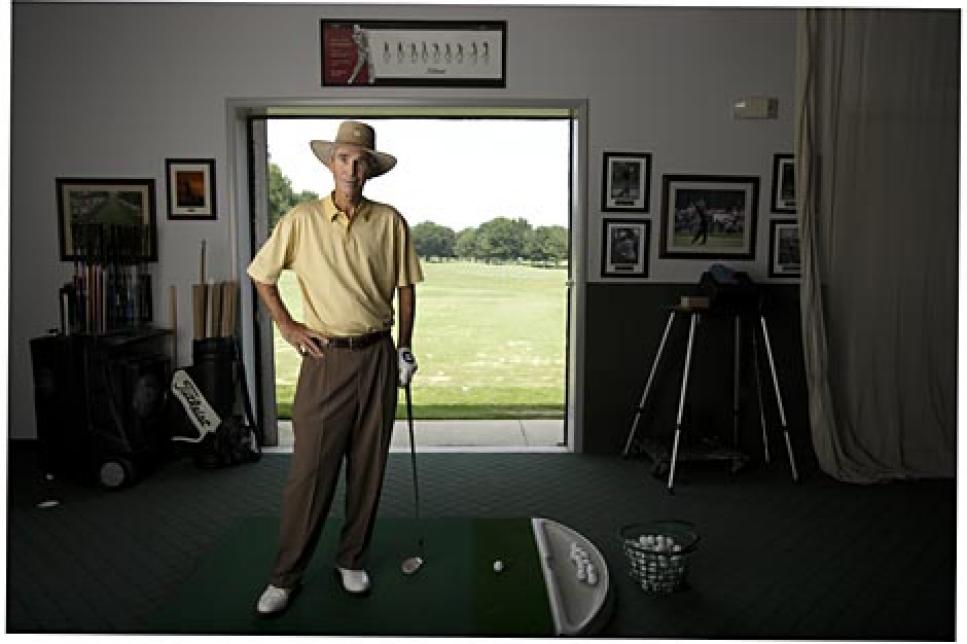

Green doesn't play much competitively, but still works on his game at Birmingham (Ala.) CC.

Thirty years later, Hubert Green wanted to talk about what he didn't want to talk about when he won the 1977 United States Open with a death threat hanging over him.

"Looking back, I didn't think it was worth talking about," he says. "Other players have used the press to their advantage. But not talking about it then was better than me saying what a great guy I was playing under this terrible threat and all that stuff. That's not me. Believe me, other players have had death threats. Tiger has had 'em."

But no other golfer ever had a death threat demanding a convoy of armed police in riot helmets or white pith helmets over the final holes of a major, as Green, in his green slacks and green-black-and-white shoes, had that Sunday at Southern Hills CC in Tulsa, Okla., where the 89th PGA Championship begins next week.

"It's a shame it had to happen, but it did," was about all he said about the threat that day. "I don't think it bothered me, but I didn't care to have my caddie too close to me, and I didn't walk with Andy Bean," the other golfer in his pairing.

Then and now, that's Hubert—quick wit, quick wisecracks, quick smile to go with his quick swing. At 60, still weakened from what he has described as his "dance with oral cancer" in 2003, he plays the Champions Tour (where he won four times) only occasionally, but in an era with Jack Nicklaus, Tom Watson, Lee Trevino, Raymond Floyd, Johnny Miller and Hale Irwin, he won 19 PGA Tour events, including the 1985 PGA Championship—more than Julius Boros, Curtis Strange and Tom Weiskopf. On three Ryder Cup teams he had a 4-3-0 record, including 3-0 in singles. With his Nov. 12 induction into the World Golf Hall of Fame, his stature is secure.

"Life's good," he says. "Got two grandkids now. Second one was just born; can't talk back yet."

Green always talked back, even when he was informed going to the 15th tee at Southern Hills that Sunday that an unidentified woman had phoned the Oklahoma City office of the FBI and claimed that three men were on their way to Southern Hills "to shoot" Green while he was putting on the 15th green. The threat was relayed to Frank (Sandy) Tatum, then the chairman of the USGA Competition Committee.

"Obviously, we had to take it seriously," Tatum recalls, "and Hubert had to know."

Tatum conferred with Lt. Charles Jones, the Tulsa police officer supervising security who commandeered the ABC television cameras to surveil the gallery. "But the security chief," Tatum says, "was convinced it all was a hoax, a gambler's hoax." Tatum didn't want to risk the worst. "I told him, Let's assume it's not a hoax, and let's assume that Hubert is shot and paralyzed, and let's assume that when he's paralyzed and sitting in a wheelchair, he asks us, Why didn't you tell me?' I think that persuaded the chief." And when Green, leading the Open by one stroke, walked off the 14th green, Tatum and Jones motioned for him to join them in the nearby trees.

"The chief hesitated," Tatum recalls, "then he said that the men wanted to hurt' Hubert, and I said, Wait a minute, it's not hurt' you, it's shoot' you.' And when we told him that a woman had phoned to tell the FBI this, Hubert said, Shee-it, you don't suppose that's somebody I've been taking out, do you?' "

There's that Hubert humor again. Talking to reporters later that day, all he said after being told about the woman caller was that he had reacted with a joke he wouldn't repeat except to say that "it came off." When asked recently what the joke had been, he said, "I have no idea. I wasn't thinking about jokes. I was thinking about trying to win the U.S. Open for the first time. I've been known to say the wrong thing at the wrong time, so it's better I've forgotten." The joke aside, he still had to decide whether or not to continue the round.

According to Tatum, Green was given two choices: keep playing or withdraw. But according to Green, he had other options.

"They told me," he says, "one, they would clear the course and continue to play. Two, they would stop play, and we would come back tomorrow morning with more security and finish. Three, we could continue to play."

Tatum remembers telling him, " You can have all the time you need to decide,' but Hubert said, I don't need any time. Let's go.' "

Perhaps, as he contended, being informed of the threat did not bother Green, but on the 15th tee, he snap-hooked his drive toward the trees to the left of the fairway on the 407-yard hole. His ball slammed into a tree trunk and ricocheted into the rough above a fairway bunker, leaving a clear shot to the green. His 8-iron left him on the top shelf, about 30 feet above the hole cut on the bottom level of the green where the phone call had warned he would be shot.

"I had told everybody else who should know what was going on—Andy Bean, the two caddies, the lady scorer," Tatum says. "When Hubert was about to putt, there were only three people on the green: his caddie holding the flag, me and Hubert."

Two years ago, Green told Golf Digest, "I won't lie to you. After I got that death threat, I was scared—not from the threat, but from being at the top of the leader board in the U.S. Open. I was a little more nervous playing the 15th hole, though, because that's where I was going to be taken out. I was a long way from the hole, and when I stood over the putt, I suddenly got the sensation I was going to be shot at any second. As soon as I hit the putt, I knew I'd left it short. I also knew I hadn't heard a gunshot. I said out loud, Chicken,' and I wasn't talking about leaving the putt short."

He tapped in for par around the time Lou Graham, the 1975 U.S. Open champion, was holing out on the 18th green for a 68 and 279, one under par. But when Green birdied the 569-yard 16th with a wedge off the browned fairway grass of a spectator crosswalk, he had a two-stroke lead. After a par at the 17th, he strode onto the tee of the 449-yard dogleg-right, uphill finishing hole knowing that a bogey 5 was enough to win.

"I thought I had it wrapped up," he said later that day. "I knew on my second shot I wanted to keep it out of the left bunker and not plug it in the right bunker. I hit a real good drive, but it was a hair too far in the rough. I hit a 4-iron because I wanted to be over rather than short. I told myself just don't knock the ball in the left bunker. And that's where I hit it, in the left bunker. Then I told myself, Don't blow it out short and three-putt, don't chunk it. I chunked it about 30 feet short, but at least it was an uphill putt. I'd practiced that putt all week, and I told Shayne [Grier], my caddie, This is the putt we practiced all week.' I hit the first putt as good as I can hit it."

But the putt stopped "about 3½ to 4 feet short," as Green estimated. If he missed it, he would be in a playoff with Graham the next day.

"I could hear people laughing at that. Oooh, he's got a little gut-stringer here,' " he says. "I had a ball mark on my line, so I called an official over for a ruling, and he told me I could fix it. Then I called Andy Bean over, and he agreed with me, then I fixed it."

Green crouched over the ball with the 55-year-old hickory- shafted blade putter he had obtained in a swap with a high-school buddy.

"I had asked Shayne what he thought," he says, "but he was quiet. I asked him again. He said, Straight in.' I said, Thanks a lot.' I don't like straight putts. That's the hardest putt for me. I had to play it straight, not a little right or left. I want to play it left-center or right-center. But it went in. I don't know how I played it, but I played it properly. I don't know how."

For all the commotion about the death threat, Hubert Green knew that he was alive and well and the U.S. Open champion.

"I don't think they told me it was a woman who called," Green says. "And if it was a woman, I have no idea who it could be. I don't know that they ever got her name. I never looked into it. I never asked any questions. I never worried about it. I didn't believe in it. I also have no idea who the men were who were coming to shoot me. I didn't ever worry about it. I just told my caddie to walk ahead of me, and I walked back with the policemen behind my caddie. The next year at Phoenix, there was a message on my locker, something along the line of Sorry I missed you last year at Tulsa on 15. We'll see you today.' I gave it to the field staff and went to play. It had to be a joke."

His cancer was not a joke. During a routine dental examination in 2003, cancerous growths were discovered on his left tonsil and the back of his tongue. In six weeks of chemotherapy and radiation at Shands Hospital in Gainesville, Fla., he lost more than 40 pounds. He also lost much of his golf game.

"I've been out for four years now, and according to my doctors, they've had no one who had a relapse after four years of being clean of that same type of cancer. I still can't eat very well. I can't swallow food. I have to wash it down. I wash it into my tongue. My voice changes every day. Sometimes I'm a tenor, sometimes I'm a bass, sometimes I can't talk at all. It varies according to the time of day. I'm better in the morning. I have coffee and I clean my throat out. I have to drink a lot of liquid shakes, my protein. I'm diabetic. I can't play much anymore. I can't compete the way I'd like to. It's no fun being a filler."

He hasn't had a top-25 finish on the Champions Tour since 2003, but he still hits balls at Birmingham (Ala.) CC, where he grew up.

"I love to practice, always have," he says. "I'm not playing at the level I'd like to, so I'm trying to get more distance and my fairway woods are terrible. Before I got sick, I beat Hale Irwin in a seven-hole playoff on Long Island. I was only five yards shorter than Hale off the tee then; now he's 30 yards longer than me. I had so much radiation, the muscles in my shoulder have given me a smaller shoulder turn. I never had a big turn in the first place. My stamina's not what it used to. And when I practice, I hit out of a building sometimes because I'm supposed to stay out of the sun, thanks a lot. Doctors don't care about your golf game, they care about you living. But I'm definitely positive. I'm alive."

As alive as when he won the 1977 U.S. Open after that death threat.