News

Nonconforming Driver

On the 36th floor of 1180 Peachtree, a sparkling office tower in the heart of Atlanta's Midtown district, you'll find the world headquarters of the pre-eminent law firm in the southeastern United States. There, in the office of the chairman of King & Spalding, along with views of the city's skyline and the stately executive décor, stands one highly inconsonant tchotchke: a fire hydrant--a genuine, old-fashioned, 200-pound cast-iron plug. Attached is a small plaque that reads: "Being chairman of King and Spalding is like being the only hydrant on a block full of dogs." Over the years the chairmen of the firm have come and gone, but the hydrant remains, a sturdy testament to both the brush fires and dog days of managing hundreds of lawyers worldwide.

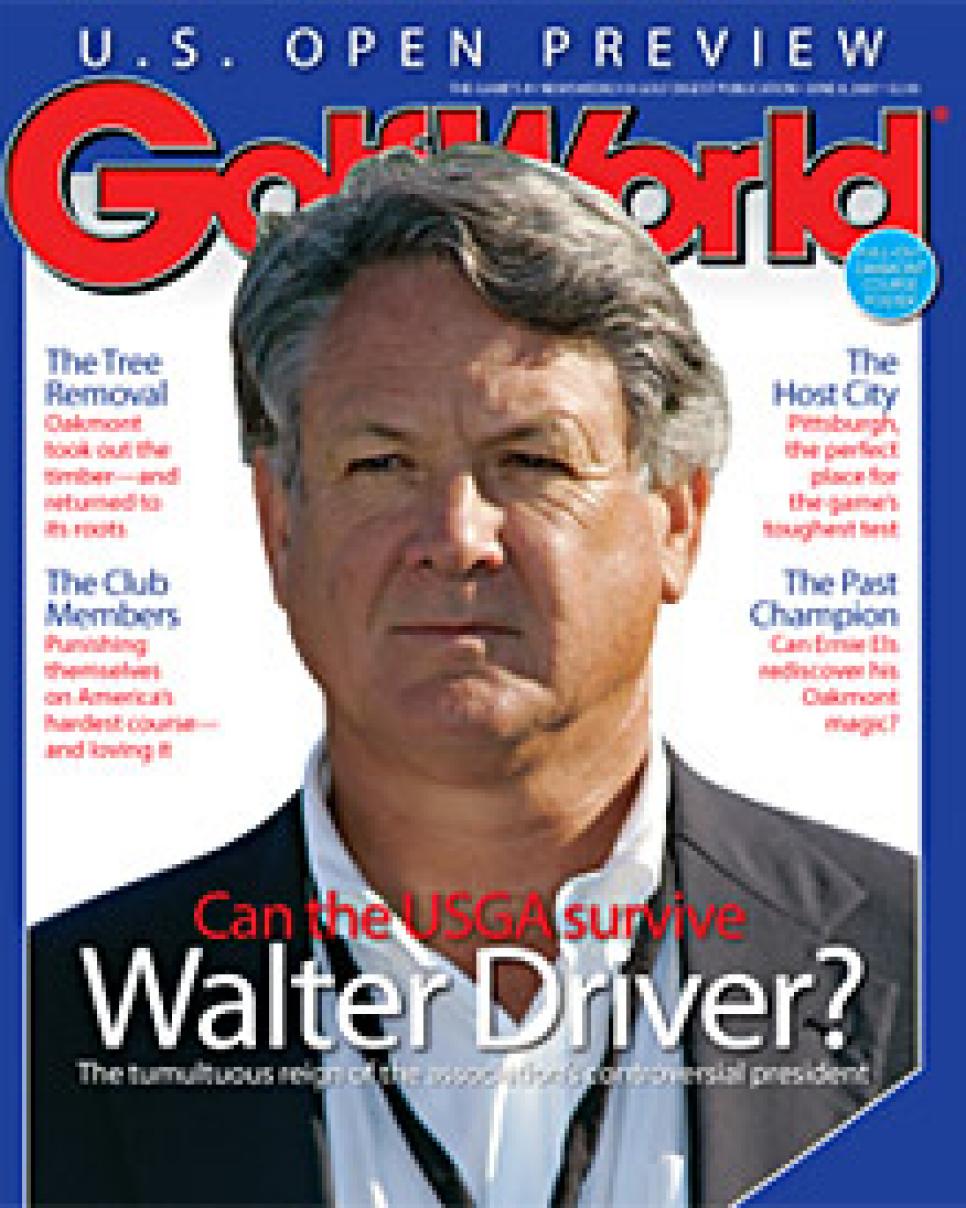

Walter Driver Jr. retired as chairman of King and Spalding in 2005. "Retired" is probably not the word. Driver traded in a career of putting out fires and promptly took up the hobby of starting them. By day, Driver has continued on the establishment path. After cultivating K&S from a highly respected old-line Atlanta firm with a cozy 40-lawyer office into a cutting-edge international powerhouse with more than 800 attorneys, the strapping Texan parlayed his stature into the chairmanship of the southeast region for alpha investment bank Goldman Sachs. But more importantly, at least to golfers, he is serving his second and final year as president of the USGA, pro bono arsonist in chief.

Driver is as reserved a gentleman as you will find. His friends use terms like "quiet," "smart," "a man of few words" and "curious" to describe him. For a man of his imposing frame and good looks, he is surprisingly soft-spoken, almost shy. He speaks with painstaking, lawyerly attention to each word. Ask a simple question and you get a simple answer, generally accompanied by a legal waiver. Something along the lines of:

"Nice weather we're having, isn't it, Walter?"

"In the eyes of some, perhaps many, yes, but I would caution you against using current measurements to predict future performance."

And therein lies the mystery of Walter Driver: How does a man so apparently traditional, so reserved, so seemingly introverted, find it in himself to take a respected--even beloved--112-year-old, nonprofit entity and stand it on its ear?

Proponents of Driver say he has single-handedly shaken the USGA out of a slumber induced by the influx of cash the USGA fell into when it reconfigured its television rights contracts in 1994. They say he has tried to inject into a bloated USGA some badly needed business principles (the title of Driver's speech at the USGA's annual meeting in San Francisco last February was "The USGA As An Organization And A Business"). Detractors, many of whom see the USGA as a charitable organization first, say Driver has imposed his will on its culture and that his administration has disenfranchised everyone from Golf House staffers (those who work at USGA headquarters in Far Hills, N.J.) to equipment manufacturers to the organization's once-revered past presidents.

"I would say his effort to instill a new level of business-like procedure at the USGA has been important," says Reg Murphy, USGA president in 1994-95 and the man who authored the association's lucrative TV move from long-time partner ABC to NBC in 1994. "He's tried to create a more business-like organization. There are people who resist that idea, by the way, that the USGA ought to operate like a business."

Asked if some of those steps have rattled the culture, Murphy replies, "There's not any question about that."

Many in USGA circles, most notably the tightly controlled 15-member executive committee, support Driver, but his tactics and style have led to the greatest period of cultural tension and employee unrest the organization has known. From unprecedented micromanagement by the executive committee to the cutting of staff benefits to confusing internal and clumsy external communication, Driver's decade with the USGA has been increasingly uneasy. Throughout his tenure, which began as USGA general counsel, critics have questioned his initiatives, whether in the minefield of equipment regulation or in the heated debate over the USGA's recent partnering with corporations. While subsequent championships have been well-received, his arid course setup for the 2004 U.S. Open at Shinnecock Hills (he was chairman of the USGA's championship committee at the time) was an embarrassment. With rounds played (a key indicator for the game's health) softening and more golf courses closing than opening last year, the game's growth has stalled. Even those who judge the USGA solely as a business--by its financial performance--have found reason to complain.

Driver has been cast as the heavy, a job for which he has seemingly been groomed: Nothing like herding hundreds of lawyers around the world if you want to get in shape for a little conflict. Since volunteering with the USGA in 1997, he has taken on some of the most contentious and controversial issues facing the organization and the sport at large. Only two months into his role as general counsel, Driver received a call from then-technical director Frank Thomas notifying him there was a nonconforming driver on the market.

"I said, 'Why don't you call the company and tell them that it's nonconforming and that you're going to send them a letter of nonconformity,' " recalls Driver. "That was on a Wednesday and on Friday they had filed suit against us."

When asked if he then began to wonder what he had gotten himself into, Driver responds, "It crossed my mind."

If Driver's honeymoon wasn't already over, it came to a screeching halt one year later when the USGA, less than a decade removed from a bruising battle with Ping over the grooves in its irons, was forced to address the trampoline effect in oversized drivers--which led to the infamous coefficient of restitution (COR) debate--and the threat posed by rapidly advancing ball technology. Almost uniformly, the association's critics accuse the USGA of adopting a defensive posture on these issues, rooted (they suggest) in the agonizing case over grooves regulation.

On COR, Frank Hannigan, who began working for the USGA in the 1960s and was its executive director from 1983-89, says, "They could have done the right thing: establish COR at the [level of the] best performing metal drivers of the 1990s, say Callaway drivers. This would have angered manufacturers and golfers and a lot of other people, but it would have been the right thing to do."

Many believe that by ultimately setting COR at .830 the USGA had seemingly recognized its mortality: If the USGA got too tough on trampoline effect, millions of golfers who were enjoying newfound distance would simply ignore them. In fact, Hannigan claims that with regard to COR one recent former USGA president told him, "We thought we were betting the franchise on it."

If the view that the USGA should have fought to the death on COR can be described as idealistic, Driver's view is correspondingly pragmatic. He explains that the clubs in question were manufactured and bought in good faith and had earned the USGA's seal of approval. If the USGA had gone back even further on COR, he says, "I don't know whether we would have had the resources to buy all those clubs or to compensate the manufacturers for relying on the letters that we sent out.

"We didn't see that it was appropriate or feasible to renege on what we had told the golfing public," he argues. "I don't view that as defensive at all. I view that as taking the most aggressive stance we thought was feasible."

Closely on the heels of the COR decision, Driver and the USGA were confronted with the evolution of the ball. In the late 1990s several manufacturers approached the USGA and said they would soon have the capability to make a single ball that combined the best characteristics of balata balls and distance "rocks." If the new ball was ever marketed, it had the potential to provide balata players with 16 to 18 yards in distance and to grant "rock" devotees much greater playability. Regardless of the ball that eventually emerged, manufacturers and the USGA would have to be mindful of the Overall Distance Standard (ODS) for golf balls established in the mid-1970s. The "rocks" of 1998 were already extremely close to the ODS limit. The softer balata balls were well short of the limit.

"The only option was to change the ODS and move it back to where soft balls were," said Driver. "The effect would have made 74 percent of all balls previously approved nonconforming. None of the hard-ball manufacturers knew how to make a soft ball, and the soft-ball manufacturers had patents on it. So based on this prediction of a new ball, but not proven fact, are you going to outlaw 70-odd percent of all the balls being played--which tend to be the balls played by the average golfer because they're less expensive and more durable--and are you then going to favor the manufacturer who has patents on the soft, shorter ball by doing that, which would have likely created chaos in the golf world and a lot of antitrust and legal issues in order to protect against something that might happen?"

Adds Driver, "It was the most complex issue and series of challenges I've ever faced in my career." This from a man who, while at King & Spalding, argued and won the largest bank fraud case in U.S. history. The USGA's thinking on COR and balls and their subsequent actions on a range of issues have left many pointing to a change in the culture of the USGA. Terms like identity crisis are tossed around (says one former staffer, "The USGA wants to be the center, but they don't want to have to decide the hard issues"). Staff morale, typically high in bucolic Far Hills, is said to have plummeted. In an almost unheard-of act of open revolt, one long-time employee recently sent a vituperative e-mail to committee chairmen roundly criticizing the executive committee's recent decision to cut benefits. The e-mail, obtained by Golf World, reads in part, "I can assure you the staff got a clear message from this executive committee about how much they value our efforts."

Traditionalists from outside Far Hills have been sharing their dissatisfaction with the direction of the USGA for years. In 2005 former PGA Tour commissioner Deane Beman sent a letter to Fred Ridley, Driver's predecessor, questioning the willingness of the USGA to stand up for the game. Jack Nicklaus, blaming distance for the increasing irrelevance of thousands of quality golf courses, has been advocating a rollback of the ball for years. Under Hootie Johnson, Augusta National seriously considered designating a shorter ball for Masters use. Geoff Shackelford, author, course architect and avowed traditionalist, is among those who closely track the USGA. He says the association's apparent lack of will on distance is causing the USGA to lose ground not only with staffers and the game's insiders, but with its very bread and butter: golfers.

"They're irrelevant with the manufacturers, they're irrelevant, or getting there, with the tours and they're irrelevant to the good player at the elite clubs in the United States," says Shackelford. "They've lost the last people they'd hoped would be on their side."

One eye-opening example of the USGA's tenuous position can be found in the recent spate of non-conforming drivers that have inadvertently found their way to the market. Nike, Callaway, Cobra and Cleveland offered to replace the offending models with conforming ones, but, says one equipment exec, "The feedback we're getting from retailers is a lot of people have said they actually want to buy one. ... That, to me, is frightening."

Concerns about the association's identity have been exacerbated by actions taken by Driver and/or the executive committee on other issues, actions seen by many as less than central, or even contradictory, to the USGA's mission. Among recent examples:

Micromanagement: One of the most stultifying trends at Golf House is the diminishing role of staff. The executive committee is supposed to act as a resource for staff, but it's the staff, under the direction of the CEO (in this case, USGA executive director David Fay), which is responsible for generating ideas, presenting them to the board, getting approval and pursuing the work. Today that is decreasingly the case.

"[The sense is] the top 60 or 70 staff people are not sitting at the table anymore," says a former USGA employee. "You have executive committee members summoning specific staff to the table, sending them away and deciding things, and sometimes not even telling them what they've decided or--even discussed." Says one current staffer, "The last two administrations have been very hands-on. Personally, I'd say too much. I think they've gone too far."

One current example of this trend is the case of Cameron Jay Rains. Rains is the co-chairman of the 2008 U.S. Open at Torrey Pines. He is also a member (since 2003) of the executive committee. This circumvents the time-honored practice in which local championship chairs report to USGA staff. When asked whether the arrangement presents a conflict, Driver says, "He was the chair of the '08 Open before he came on the executive committee, and we essentially screened him off from any potential conflict." Pressed to admit Rains' dual interests could at least raise some eyebrows, Driver is dismissive. "Doesn't work that way," he insists.

Some observers aren't so sure. "The person negotiating on behalf of the city of San Diego [Rains] is also on the USGA executive committee," says Shackelford. "He's on both sides of the table. So when San Diego [officials] want to know how many hats were sold and what their cut of the revenue is, this isn't a problem? Who is [Rains] looking out for? It's just astonishing."

Rising expenses: With a nest egg conservatively estimated at $290 million, the USGA is awash in cash. Still, the association has been on a notable spending spree. In 2005 total USGA expenses were $97 million. By 2006 that number had risen to $133 million and had contributed to a rare operating loss estimated at more than $6 million.

When asked what's at the root of the losses, Driver says, "We're spending more money than we're taking in." Pushed to be more specific, Driver explains, "Money is fungible. You can spend money or save money anywhere. All the dollars count the same." Others close to the USGA pinpoint U.S. Open site selection as the culprit. Venues with ample acreage for parking and hospitality generate more revenue than land-starved venues such as Winged Foot, which hosted the 2006 Open.

Fungible or not, the USGA needs to start watching its wallet. Ex-executive committee member Craig Ammerman told the Philadelphia Inquirer recently that money was among the biggest issues facing the USGA. Past president Murphy concurs. "The long-term financial outlook of the USGA is good but not outstanding," says Murphy. "It's not going to make a whole lot more money in the next five or six years than it's going to spend. In fact, there are some loss years there."

The keys are the USGA's television contracts with NBC and EPSN. Driver hints the USGA is looking deep into the future of sports media. "We have our TV contracts signed through 2014," he says, "but I can't predict for the USGA what the distribution of golf video will be like in 2014, [only] that it won't be just like it is now. We need to have a more diverse source of income, and we need [a plan] so we don't get caught where we are dependent on one thing and find out the world has changed."

Fittingly, rumors are circulating at the USGA that Driver, who brought King & Spalding to the cutting edge of technology, is looking to bring in a media czar to help define the future of the USGA's rights portfolio. Additionally there has been discussion of hiring a senior-level executive to manage all USGA revenue.

Disgruntled staff: Far Hills is one of the New York-area's priciest suburbs. Typical of a non-profit, however, the USGA does not pay particularly well. According to IRS filings, few USGA employees aside from the most senior management make more than $50,000 (executive director Fay does earn well over $500,000). For that reason, USGA staffers have long relied on a generous benefits plan to help mitigate the cost of living. Nonetheless, in February USGA staff was notified of significant cuts to their medical plan. Further, the Educational Assistance Program, a prized USGA benefit, which since 1997 has assisted Golf House employees with the cost of a child's college tuition, would be phased out.

Compounding the issue--and confounding staffers--were the following: First, only weeks prior to the revelation that benefits would be cut, the USGA had signed two new deep-pocketed corporate sponsors. Second, less than a year before rumors of the cuts reached Golf House staff, news media had revealed that the USGA had acquired time on a private jet for use by the president and the executive committee. Third, on Feb. 3, only days before the announcement of the cuts, Driver had presided over an upbeat annual meeting at the close of which he said, "I want to thank our great USGA staff," and added that in "order to build the best staff possible" and to "recruit and retain top talent," the executive committee was undertaking a review of compensation and benefits.

On Feb. 6 USGA staffers were advised of the benefit cuts via memo (a copy of which was obtained by Golf World). The cuts, their timing and the manner in which they were presented stunned and angered employees. "The way it was couched to us, they were basically taking something away without really telling [us] what was going to happen," says one USGA veteran with college-aged children. "A lot of people here felt that wasn't fair."

In the previously mentioned e-mail that was eventually routed to executive committee members, one outraged staffer wrote, "So the bottom line remains that despite all the great work we did during the year, despite all the financial gains made by the association and despite all the kudos thrown our way, the executive committee thanks us by cutting our benefits."

In an unusual move, Driver flew to Far Hills to quell concerns. "The staff had not been given what I call the 'three-legged stool,' and I wanted to explain to them the process," says Driver.

Outside observers were flabbergasted. "Walter Driver [saying] in his address we've made changes to help us improve our potential for getting quality staffers in the future--when in fact they were cutting benefits--was the ultimate corporate act: Say one thing and do another," says Shackelford, who frequently posts provocative and acerbic comment on his blog. "For me that was the all-time low, really."

Past Presidents: In 2004 an amendment was adopted that gave a reduced role to elder past presidents, who played a leadership role in the executive committee nomination process. Their voting power was cut from five votes to two. That has left a bitter aftertaste and, as a result, some of the game's most respected elder statesmen have been alienated. Bill Campbell, a legendary amateur and USGA president from 1982-83, has taken a self-imposed sabbatical from any business with the USGA. Asked by Golf World for comment, Campbell politely declined. "I don't want to get in the way," he says.

Driver, who would not become president until two years later, says he had no direct role in the amendment, but nonetheless the USGA is paying the price in decreased goodwill among the older blue-blazer set.

Air Fair: Before Driver took over, longstanding USGA tradition called for executive committee members to pay their own travel expenses for association business. Once disclosed, the idea of a USGA-funded private jet for executive committee use sent shockwaves through a century-old volunteer ethos. One former president who asked not to be identified says, "I have been away from the institution for a long time. Priorities and demands change. For example, a jet for executive-committee use would have been unheard of in my time."

Driver has been demonized as the procurer and chief beneficiary of the plane when, in fact, he inherited the lease from Fred Ridley's presidency. The deal with Citation Shares was made, ironically, at the suggestion of the past presidents. Driver is unruffled by the controversy. He considers the plane a tool, one that has allowed him to expand his USGA schedule. "If people don't think it's appropriate," he says, "either I or the next president simply won't do those things."

Grooves Redux: In February the USGA forwarded a proposal that calls for a reconfiguration of grooves on irons. Using research based on observations of a handful of unnamed "tour" players performing test shots from light rough, the proposal advocates grooves with less volume, and with a dulled top edge. Oddly, the impetus for the grooves proposal was the state of play on tour, a very small but highly visible slice of the American golf community. "The fact that really stimulated this," said Driver, "is that during the last several years there is no correlation at all between fairways hit and money won on the PGA Tour. Clearly, you can hit it anywhere. Part of that is the grooves. We think we can demand more skill [by] making you drive the ball in play."

Few would doubt that length is an issue, but are there options short of a new grooves proposal? Frank Thomas served for 26 years as USGA technical director. A survey conducted by his website, franklygolf.com, shows that when asked if championship play should address grooves or simply grow deeper rough, the majority of respondents opted for deeper rough. However, when Driver was asked by Golf World if he had spoken with PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem about such an option, Driver responded, "You'll have to ask Tim Finchem." According to PGA Tour spokesman James Cramer, there have been no such discussions.

Thomas is left shaking his head. "I am concerned that the decisions or the rules with regard to equipment proposals are being based on the performance of literally 1/1,000th of 1 percent of the golfing population," he says, adding, "the USGA is doing something for the sake of doing something."

Executives at Nike and Titleist declined to comment for this story. Ping provided a statement on behalf of chairman and CEO John Solheim which called the proposal "a huge step backwards," but even manufacturers differ. John Hoeflich, senior vice president of Nickent Golf and one of the game's most respected club designers, has no problem with the grooves proposal per se, but doubts its ultimate effect. As milled wedges with more articulated grooves become standard, Hoeflich says, "Why not regulate that? [The USGA] has to react to it. The point is, though, that Tiger Woods could play with a wedge with no grooves and knock it three feet from the hole, anyway."

So it seems the modern USGA has painted itself into a corner on distance. Of course, Golf House still has the game's nuclear bomb at its disposal: rolling back the ball. A shorter ball for tour players (while the USGA has established a set of specifications under which "approved" balls must be manufactured, golf remains the only major professional sport that does not currently mandate an "official" ball) offers a lasting solution while preserving classic architecture. While that option might please people like Beman and Nicklaus, it also has its critics.

"A rollback would be suicide for the USGA," insists Thomas. Hoeflich agrees. "If the USGA rolls back the ball by say, 20 yards, [it] will lose the consent of the governed," he says. "I myself believe in playing by the rules, but the day they implement that rule I'm going to buy 48 dozen Pro V1xs, put them in my garage, and play them as long as they last. Then it's Katy-bar-the-door. Why not play a nonconforming driver or put ChapStick on the face of the club? There's a domino effect on people's opinion about rules."

One has to wonder if the USGA leadership would like a mulligan on its recent equipment decisions. "I think if we all had it to do over again ... we all would say that distance controls should have been imposed a lot earlier," says past president Murphy. "I don't think there's a significant amount of argument about that." When asked if such a rollback is inevitable, Driver says, "It would not be appropriate for me to predict in any way what future executive committees will do."

Corporate partnerships: It's unlikely Driver will do anything that will alter the organization's culture more drastically or more enduringly than his pioneering of corporate sponsorships. Whether one sees the marketing deals with American Express and Lexus as "sell-outs" or as the logical next steps for a revenue-hungry charitable organization, the question remains: How will the average member of the USGA and/or the average golfer ultimately benefit from these deals? As for individual USGA members, Driver points to better management of their information and rewards. As for nonmembers, he adds, "I think [American Express and Lexus] will teach us how to better identify segments of the population who are avid golfers, how to communicate with them, where to do it and how to do it. We've never done this as intensely or, frankly, as well as the manufacturers--or any business." (Driver was on the executive committee when the USGA shuttered its acclaimed in-house magazine, Golf Journal). USGA management has already seen one benefit: leased Lexus automobiles have already been delivered to senior directors.

The notion of the USGA partnering with corporations makes some traditionalists, including one former USGA president, uncomfortable. "I knew they were possible," he said, "but I feared commercializing a pure charity, which was unique in sports and revered for its long, pure traditions." But the same past president admits, "I felt the income from such deals would always be there for the asking, maybe at a time when the USGA was in true need of additional funds."

In a recent column for the website golfobserver.com, Hannigan reflected on the late Howard Clark, who was both a USGA executive committee member and CEO of American Express. "Trust me," wrote Hannigan, "[Clark] would not have bought into a USGA that thought it needed to do deals with his company. He would have understood that the selling of the soul is part of such a process and it's not worth the price."

Limited to two one-year terms, few USGA presidents fashion true legacies. That suits Driver, who claims to be uninterested in epitaphs. Driver's approach to the USGA work is tough love. He displays little patience for critics, many of whom he views as uninformed on issues such as distance, balls and clubs. In fact, he often begins and ends his answers on these topics by staking out higher ground, saying, "Most people just don't understand the complexity."

As the end of his presidency nears, Driver seems focused on effectiveness--getting what he sees as a wobbly USGA safely embarked into the 21st century. If the role of the USGA leader is that of a steward, Driver has been badly miscast. But if that role is to reposition the association by wrenching it from its venerable roots and steering it toward a changing future, Driver will go down as an undeniable, unforgettable, unflinching force.

"There are times when you need to be a steward and there are times when you need to change," says Reg Murphy. "There are times when you have to change the direction of an organization and times when doing things as you've always done them is a good thing, because that preserves the game in another way."

So, Murphy is asked, where are we with Walter Driver?

"Walter," he says, "is a change agent."