News

The Lessons of Turnberry

Master Negotiator: Watson worked his way around Turnberry with a Hoganesque display of solid shots many younger players didn't seem to have.

Lest it ever again slip our minds that golf is the cruelest game, the word "Turnberry" will for the foreseeable future suffice as an instant reminder. But as the wind howled through the empty bleachers surrounding the fateful final green and the sky darkened over the Firth of Clyde late Sunday evening, it was natural to wonder what the 138th British Open taught us.

First and foremost, Tom Watson's reputation as a player is adjusted upward. His feat of reaching the playoff of a major championship at age 59 has never been approached, surpassing what then-50-year-old Harry Vardon did by holding the lead over the final nine holes of the 1920 U.S. Open before sadly finishing second by a stroke. Like Vardon, and especially Sam Snead, Watson, by showing how much game he has in his dotage, retroactively raises the assessment of just how much game he had in his prime. In other words, during that period from 1975 to 1983 in which he won his eight major championships—and even in the long period after that when he barely won at all—he was better than we thought.

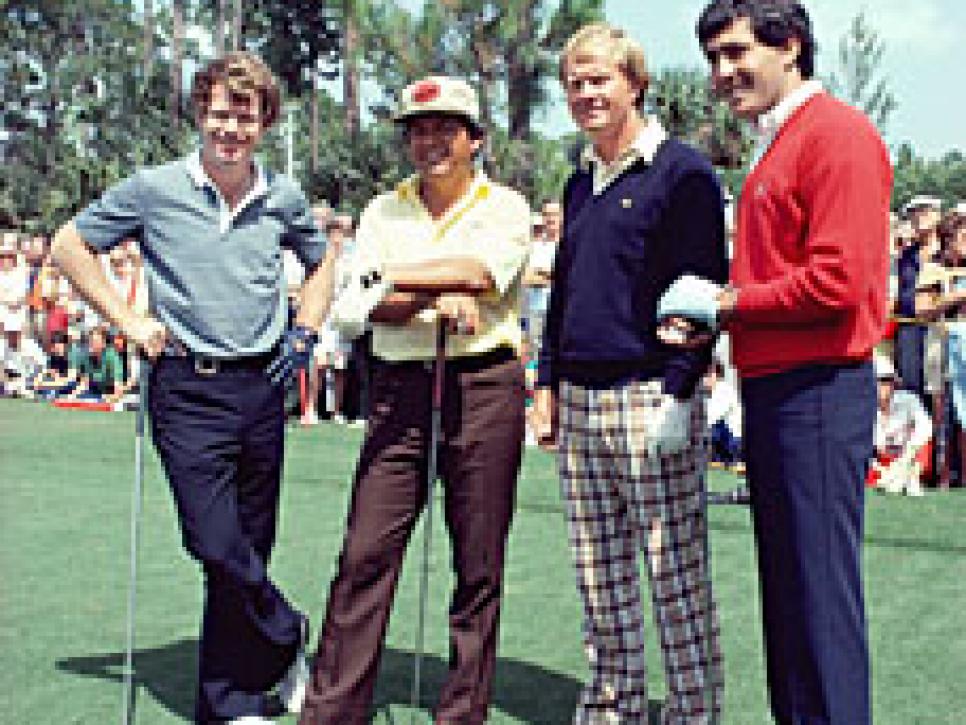

But second, the last round at Turnberry provided a revealing snapshot of the current era of golfers—and frankly, exposed them as wanting. For all their power and superior physiques and technical proficiency, the evidence keeps suggesting they are as a group (with one giant exception) competitively softer and less-accomplished shotmakers than their predecessors. And unless a few of them can come closer to being more like the giant exception, their place in history, much like the baby boomers, will end in the shadow of the golf equivalent of the Greatest Generation—a group including Jack Nicklaus, Lee Trevino, Johnny Miller and, of course, Watson—that ruled the game in the 1970s and into the 1980s.

I've been resisting this line of thought for several years, which has gained momentum as so many have folded and fallen before Tiger Woods. The argument goes that Woods has it easier than Nicklaus did when it comes to racking up majors, because of the greater number of proven winners and presumably tougher, hungrier and more well-rounded competitors that the Golden Bear faced. For all their vaunted depth, today's players, the theory goes, suffer from a general decadence: too much prize money lowering the urgency to win; too few moments atop leader boards leaving them relatively callow under pressure; and too many equipment advances that keep increasing distance, accuracy and spin while lulling them into a one-dimensional style of power golf that is ill-suited to the demands of major championships, particularly those played on a links.

For a while it seemed that a basic foundation for this polemic was nostalgia. It tends to ignore that Nicklaus and others picked up plenty of their majors when lesser players buckled. It also seemed an intentional slight to Woods, devaluing his breathtaking record for winning tournaments when holding or sharing the lead going into the final round (45 for 48 in his career, and 14 for 14 in majors), which to my mind is his most extraordinary feat and the one that most distinguishes him from the champions of previous eras. Finally, it runs contrary to the principle that is generally accepted across all sports—that athletes keep getting bigger, faster and stronger while increasing their skills.

However, I've been getting worn down as the game's wise heads have become more insistent. Sure, players from the previous era have a clear conflict of interest, but veteran caddies, who have worked in both eras and have been best positioned to see the difference, don't. Though they prefer not to be quoted, most believe the older players were tougher and better all-around players. "They can get rich without being that good now," more than one grizzled looper has told me of the current crop.

Turnberry gave this school of thought more credence. It was the kind of examination that asked the variety and type of questions modern players have a hard time answering. As Luke Donald, who closed with 67 to finish T-5, said, "They don't the winner the champion golfer of the year for no reason, because this really does test all facets of your game."

Sunday's final round was most telling. Neither the wind nor the pin positions seemed extreme. Padraig Harrington, after ending his defense of the claret jug with an early finishing 73, declared, "Anyone can get it under par today. … There's hardly a pin on the golf course if you hit a good shot you can't get close to."

Yet birdies were scarce, and 67 was the best anyone did. Cink said it was because of Turnberry's tricky crosswinds. "You just don't have any margin for error with the way you start your shot, with the trajectory or the spin," he said. "You just have to be right, or you're going to miss your target, no question. It was just the perfect amount of wind to challenge everybody and see what everybody had."

It just didn't seem that the main contenders—the ones by definition doing the best playing—had that much. One after the other they failed when presented with a main chance. First Ross Fisher reacted to a sudden three-stroke lead after the first four holes by making a quadruple-bogey 8 on the fifth, and never recovering. Ernie Els, a stalwart of the era, got to even par by playing the first 10 holes in three under, but he could get no further and missed a six-footer for par on the last that ended all hope. Retief Goosen, who has not been quite the same since taking a lead into the final round of the 2005 U.S. Open at Pinehurst and shooting 81, was within one when he took two in the bunker and missed a four-footer to double bogey the 15th. Mathew Goggin was tied for the lead through the 13th, but three straight bogeys and a failure to birdie the easy par-5 17th left him two out of the playoff. Even Chris Wood ended his 67 with a missed 10-foot par putt on the 72nd that would have tied him with Watson and Cink.

The most regretful "nearly man" besides Watson was Lee Westwood, a prolific closer early in his career, who once again didn't get it done. His long-suspect short game found him out: A clumsy bunker shot on 15 and an anemic chip on 16 led to bogeys that were more egregious than his three-putt on the final green.

Even Cink looked as if he had blown it. After his third birdie on the back nine at 15 put him in a tie for the lead, he promptly took three from the edge for a bogey on the 16th and failed on a six-footer for birdie on the 17th.

But Cink has been steeled by failure, putting himself through the same process—brutal self-assessment and determined correction—that once changed Watson from a young player prone to choking to a champion who could face down Nicklaus. "Somebody at a major always has that calm peace about them," said Cink, who was the embodiment of cool with his 72nd-hole birdie putt.

For the four days he commanded center stage at Turnberry, it surely seemed to be Watson who had the corner on calm. His swing, now long distilled to its functional essence, was a study in rhythm, balance and repetition. His expression, even over the short putts that for so long have been his nemesis, was one of inner joy. As he put on a Hoganesque display of exceedingly solid shots that masterfully negotiated Turnberry's winds and nuanced angles, younger competitors didn't contain their admiration for a player who seemed to have emerged—slightly wizened but playing a game with which they were not really familiar—from a time capsule.

"He's so solid, and he hits the right shot," said Cink. "He just plays under control. The same Tom Watson that won this tournament in 1977, that same guy showed up here this week."

Watson is the essence of old school and believes the game has devolved in decadence in recent years, but he didn't throw any darts at Turnberry. "The big-headed clubs make you a little sloppy," he allowed. Asked directly about the current era of players, he half-ducked. "Well, that's for you to write," he said. "But there is that element of 'Who is challenging Tiger?' "

Though he didn't win, when it came down to it, until the very last green, it was Watson who handled the pressure with the most poise and aplomb. He hit full-blooded shots throughout the back nine, particularly on the final three holes. As he had said, "The reason I'm out here is I hit quality shots when the pressure's on." And he did. The great irony of Turnberry is that the man who had grown to love the unpredictable bounce of the ball on a linksland was undone by the meanest of bounces after flushing a seemingly perfect 8–iron approach into the 72nd hole.

So, here's the takeaway: Yes, Watson is a supreme talent and truly extraordinary golfer, even greater than we knew. Yes, his inability to carry the ball through the air as far as the young bucks is rendered moot on a championship links. But sorry guys, all-timer or not, links or no links, if a 59-year-old guy looks like the best player in the field at a major championship, there is something wrong with your era.

At the presentation ceremony, Watson stood with 16-year-old Matteo Manassero, the dynamic Italian amateur who finished T-13 after his own disappointing 5-5-5 finish. They had played the first two rounds together, and Manassero was the better for it. "Playing with Tom Watson," he said, "even if he doesn't say something to you, even if he doesn't give you advice, you grow up [by] watching him."

Though he didn't complete the storybook, Watson put on a clinic for the ages. Perhaps Manassero's era—the next one—will be freer of the excesses that have hurt this one. Maybe there will be more equipment rollbacks, and, who knows, less money.

Until then, let's hope the lessons of Turnberry were well learned.