News

Role Reversal

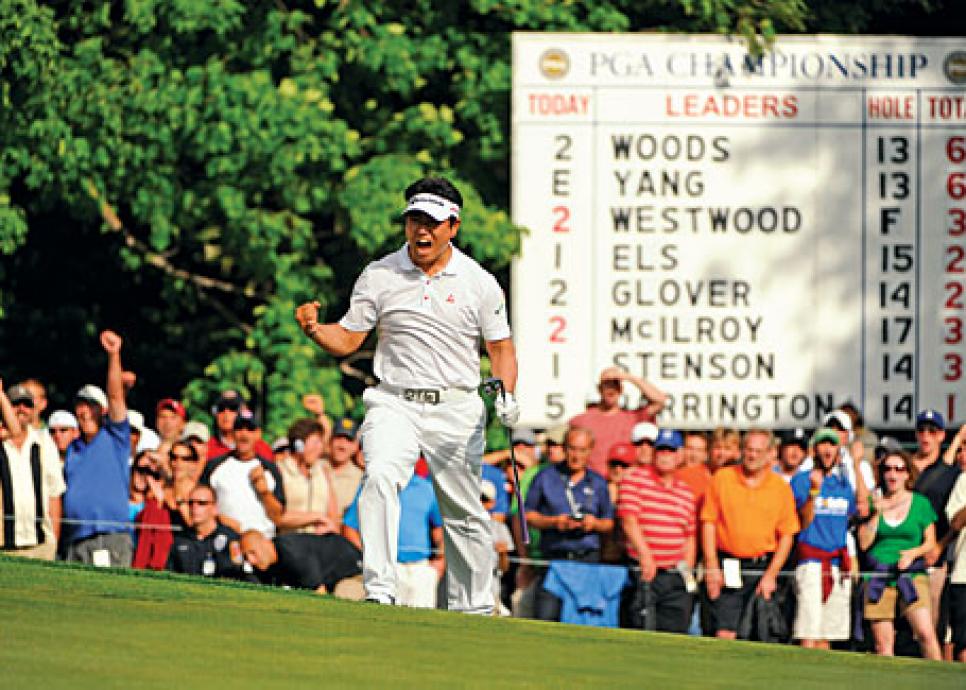

the eagle has landed: Yang's dramatic hole-out for a 2 on the 301-yard 14th hole Sunday gave him a lead over Woods that he never relinquished.

In China it's the Year of the Ox. In South Korea it's the Year of the Yang. And in golf it's the year of Who Moved My Cheese? When the first three major championships are won by a guy nicknamed The Duck, a golf pro who actually reads books and another one who Tweets, only a slow learner wouldn't bet the ranch on Y.E. Yang over Tiger Woods in that year's PGA Championship. Stand back people, we've passed into an alternate universe.

First, it was Angel Cabrera who wasn't supposed to beat Kenny Perry. Then, Lucas Glover wasn't supposed to beat Phil Mickelson. Nor was Stewart Cink supposed to beat Tom Watson. So at the PGA, on the Wobegone Links of Hazeltine National, where all the par 5s are strong, all the fairways handsome and all the golf pros above average, Tiger Woods, who is supposed to beat everybody, didn't. Quick, call rewrite.

Yong-Eun Yang delivered two of the finest golf shots of the year, one short and one long, in a five-hole stretch to snatch a 15th major championship straight from Tiger's toothless jaws. Such things are simply not done in polite company—at least never on any of the 14 previous occasions when Woods went into the final round of a major championship with a lead. Of course, those were the good old days when he holed putts. Woods' major titles, coupled with the fact that the 37-year-old Yang was the 110th-ranked player in the world who, until he won the Honda Classic in March, was aspiring to little more than keeping himself out of Q school, combined to give the impression that if this wasn't the biggest upset in the history of golf, it had a seat on the bus. To borrow a phrase from the world of politics, however, championship golf ain't beanbag. So, get over it.

By the time Yang and Woods reached the 13th tee on a windblown Sunday, they had managed to separate themselves from the field. Everyone was waiting for Yang to fade, but Woods wasn't playing well enough to give him a reason. They were six under par, and the next closest competitors were three under and all of them proved incapable of closing that gap coming home. At the 240-yard 13th Yang hit a utility club into the front-left bunker while Woods knocked his 3-iron to roughly 10 feet. Yang blasted out to eight feet and holed the putt while Woods missed to keep them both at six under. On the 301-yard 14th, they each hit driver. Woods found the bunker on the right while Yang was just short of it, 30 yards away. Woods' explosion shot stopped 10 feet short, and Yang pitched in with his 52-degree wedge for an eagle. Woods should send Yang a bill for fist-pump royalties. For the first time since Thursday morning, Tiger wasn't atop the PGA leader board.

The son of a farmer and once a sergeant in the South Korean Army, Yang was the only contender who ever wore a uniform or carried a weapon, so you had to figure the son of an American Special Forces officer probably had a pretty good idea all along he wasn't playing Mary Poppins. Woods just couldn't hole anything. He missed makable putts—and by that let's call them inside 15 feet—on the first, second, fourth (to three-putt), 10th, 12th, 13th, 15th and 17th. He took 33 putts in all. It was not his finest four hours. True, it's not like they were a bunch of three- or four-footers. He's not Vijay Singh, after all, but it was a bad day to have a bad day.

"I played well enough to win the championship," said Woods. "I did not putt well enough to win the championship." Truer words …

It was Yang who seemed more like Woods than Woods, striking a majestic 3-hybrid from 210 yards out of the first cut, arcing it high over a broad-leafed tree, to eight feet on the 18th green, resurrecting memories of both Shaun Micheel in the '03 PGA Championship at Oak Hill and Woods himself on that very hole seven years earlier. Woods followed by missing the green left, trying to hole his chip shot and finishing with a meaningless bogey to Yang's birdie. He was three shots behind the South Korean's winning total of eight-under 280 as Yang became the first Asian-born male to win a major golf championship. More fist pumps. More royalties.

"We played that hole twice in the practice rounds," said Yang's teacher, Brian Mogg. "He hit hybrid on that hole both times and almost holed them. I had a vibe during the week that this was going to happen. He doesn't put too much excess pressure on himself."

That hadn't always been the case. After Yang beat Woods by two strokes at the 2006 HSBC Champions in China, the former bodybuilder carried an excess of expectations and went more than two years without winning until his maiden PGA Tour triumph this March, when swing improvements he had been working on with Mogg since 2008 paid off.

While Woods seemed puzzled at times by the wind during the final round at Hazeltine, Yang was steadfast, befitting a golfer nicknamed "Son of the Wind" in his homeland because of his ability in the breeze. "I woke up at dawn today to watch the broadcast, and you played in a calm manner," South Korean president Lee Myung-bak said to Yang in a congratulatory call. "First of all, you enhanced our people's morale by winning the major title for the first time as an Asian."

Yang's historic victory ended a week that began with a lot of chatter about golf's global footprint. Supposedly, the recommendation by an Olympic committee in Germany that golf be added as a sport in 2016 was going to overshadow the first round of the PGA in Chaska, Minn., which is the Chippewa word for "there used to be Holsteins here." That was right up until the very second that the ultimate argument for golf's inclusion in the quadrennial Olympiad took a one-shot lead with an opening-round five-under-par 67, a lead he held until Yang took it away Sunday.

Woods (who, with a straight face, tried to convince everyone he didn't need to win the year's final major championship to make his season of recovery a success) had won his final event preceding the year's other majors but came up empty at Augusta, Bethpage and Turnberry. Coming into Hazeltine, he one-upped himself, winning back-to-back at the Buick Open and the WGC-Bridgestone, even if he did beat Larry, Moe and Curly in the first and, in the second, got an assist from a zebra who forgot to swallow his whistle in the fourth quarter—which, by the way, gave the media wretches something to write, tweet, blog and pundify about until someone started hitting golf shots that mattered.

Minnesotans love their sports and, since there were no conflicts with curling or ice fishing, they arrived in crowds the size of ancient buffalo herds all week. It turns out the hearty natives of the frozen tundra love golf with the same passion the desert Bedouin have for water. Apparently golf loves them back since it has given them, among other things, Bobby Jones skipping a ball across a pond at Interlachen CC on his way to the Impregnable Quadrilateral during the Great Depression and the historic upset of Woods almost 80 years later in the midst of the Great Recession.

Speaking of shots that mattered, there were a couple of illustrative ones in the early rounds. The first was Harrington's 3-wood from the bunker on the par-5 15th Friday that traveled 301 yards uphill, downwind and finished 12 feet from the hole. It was a shot strikingly similar to Seve Ballesteros' 3-wood out of a fairway bunker on the final hole of his singles match in the '83 Ryder Cup at PGA National. Woods so admired it, he told Paddy it was the kind of shot he would pay to see—whereupon Harrington asked him for $50. Woods didn't pay up, but in the hot, strong prairie wind he did take a four-shot lead over Harrington, Singh, Brendan Jones, Lucas Glover and Ross Fisher after 36 holes.

The second shot of import came Saturday on the drivable par-4 14th. In a portent of the final round, Woods had played indifferently all day, summoning as many as possible back into the tournament. The invitation was accepted by Yang (with the day's low round of 67), U.S. Open champion Lucas Glover, Henrik Stenson and, until they combined to play the last three holes five over par, Ernie Els and Sren Kjeldsen. Most especially, Harrington made good use of his first day paired with someone other than Woods in almost a week when he birdied the 14th as Tiger stood on the nearby 13th tee. It tied them briefly at seven under. When Woods got his turn at the 14th, he hit a wondrous towering cut driver that rolled just through the green. He chipped poorly, running his ball past the hole and off the green on the other side, almost up against the collar. His pace quickened as he stalked the comebacker. Clearly annoyed with himself, he was not about to let this birdie, or his lead, slip away. He bellied a wedge into the hole for the week's first fist pump only to have it thrown right back in his face on the very same green 24 hours later.

At Saturday's end Woods claimed to be quite content with his 71, though he had failed to birdie any of the par 5s and his lead was halved to two shots. On a day when the young Woods would have tried to stretch a four-shot lead into eight, the veteran Woods was seeing more risk than reward. Was it just a bad year putting in the majors or has his transition from a force of nature into a model of consistency, in the end, made him somehow less capable of imposing his will?

If on Sunday, from time to time, it seemed as if no one could play this silly game, consider it was sufficiently windy that, for the first time in a PGA Championship since 1977 at Pebble Beach, no one could post a score in the 60s. Mini-disasters abounded, none more horrific than Harrington reprising his Firestone Snowman with another on Hazeltine's eighth, this time without the aid of rules official John Paramor.

This is Woods' second dusting at Hazeltine, having been laid out there by Rich Beem seven years ago. To He Who Is Still Without Peer, that's not a seven-year itch, it's more like a bad rash. But to Y.E. Yang and all of Asia, it was history in the making and a reason to dance.