News

The Mouth That Roared

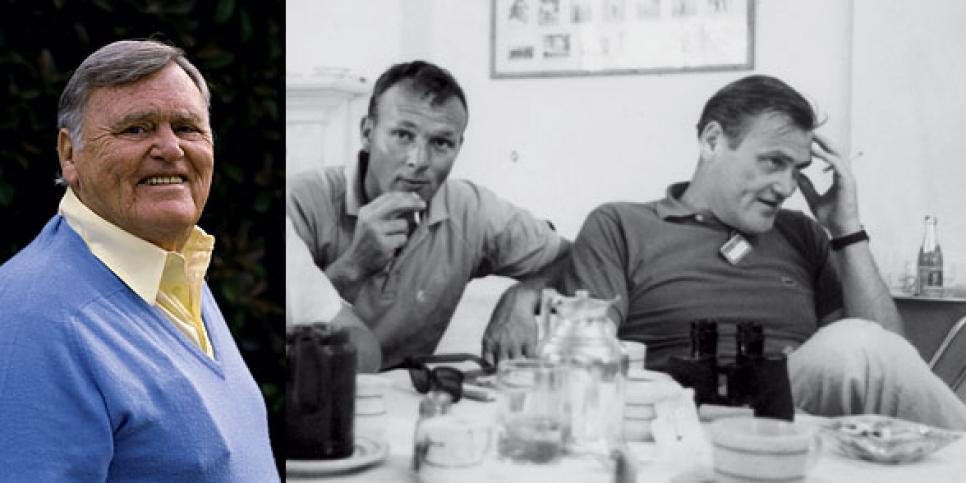

Along For The Ride: Decades before Drum became a hit on CBS golf broadcasts when he was in his 60s with popular features called "The Drummer's Beat," he closely chronicled Palmer's rise from schoolboy golfer to national icon as a sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Press newspaper from 1946-1963.

They don't make Bob Drums anymore, not that they ever made many. To meet him was to remember him. "One of a kind, without question," says longtime friend Doc Giffin, who knew Drum more than 40 years. "That phrase is used a lot, but he truly was one of a kind. Nothing held him back -- sometimes things should have."

Drum typed for a living much of his 78 years ("He lost about 50 of those little portables [typewriters] on airplanes," says his older son, Bob Jr. "He bought one of those a month."), but he lived to tell stories and crack jokes. "When I think of Drum, I think of laughter," says Dan Jenkins, who met Drum in the early 1950s when he was the golf writer for the Fort Worth Press and Drum was with the Pittsburgh Press. "We found everything funny."

Drum's voice -- deep, inflected with his Long Island roots and unaffected by going to college in Alabama -- was as large as his hulking 6-foot-4 frame, and it carried as if there was a bullhorn at his lips instead of a vodka and tonic. "If he was there, you knew he was there," says Arnold Palmer.

By 1960, when Palmer was making golf march to his enthusiastically muscular beat, he'd known Drum a long time. "He was around before the beginning," says Palmer, a teen golfer in 1946 when he met Drum. The next year Drum reported on the 17-year-old Palmer's victory in a regional event. "Arnold Palmer," Drum wrote, "stood out in the West Penn Junior tourney like a neon sign in a blackout." Drum soon opined that Palmer "ought to be quite a boy when he grows up."

"Bob was the first to notice," says Giffin, Palmer's assistant but once Drum's colleague at the Press. "He was predicting big things for Arnold when a couple of the other golf writers in town didn't have that clairvoyance."

As Palmer began attracting more attention for his play, Drum was along for the ride -- not always as a passive observer. "Do you know how many Arnold Palmer stories I wrote? Five thousand, quoting him in every one and half the time I couldn't find him," Drum told Golf Digest in 1987. "Palmer still thinks he said all those things."

Drum was building a legend of his own in Pittsburgh, clocking more time in taverns than at the newspaper. "He would come into the office about 10 a.m., check his mail, make a couple of phone calls and he was gone," Giffin says. One time Drum's stepfather, Howard Morris, happened to be in the city on business and came into the Press hoping to find Bob.

"He asked the executive sports editor, Al Tederstrom, if Bob Drum was there," recalls 94-year-old Roy McHugh, a veteran Pittsburgh reporter. "The sports editor was editing a piece of copy. He didn't even look up and said, 'Nope.' 'Do you know when he'll be in.' 'Nope.' 'Do you know where I can find him?' 'Nope.' Drum's stepfather said, 'I'm passing through and don't get to see him very often.' For the first time, Tederstrom looked up and said, 'Neither do we.' "

Had Morris known where to look, he could have found his stepson in no time. Drum hung out at the Travel Bar in the Pittsburgher Hotel downtown by day and Dante's in the suburbs at night, when he wasn't listening to jazz at a nearby joint, sometimes with Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Bobby Layne and a coterie of other Steel City notables. Sometimes Drum would write stories on cocktail napkins and send them to the paper in a taxi -- collect.

"Bob was much funnier in a bar or at the dinner table than he was in print," says Jenkins. Drum's counterpart among golf pros when it came to living the good life on someone else's dime was putting savant George Low, a sometimes traveling companion. Asked what it was like to share a hotel room with Low, Drum quipped, "Taking a shower with your wallet in one hand is too much trouble."

"Dad didn't like writing. Writing was hard," says Kevin Drum, the youngest of Bob and M.J.'s five children. "There's a solitary writing life, and then there's being around people. One's easier than the other. He could hold court, no matter how big the place was."

Appropriately enough, in 1960, Drum achieved a lasting impact on golf because of things he said rather than wrote.

After winning the 1960 Masters with a fantastic finish, Palmer spoke about wanting to win the U.S. Open and PGA Championship. He didn't mention it at Augusta, but because the British Open was going to be played at St. Andrews, he had that tournament on his schedule from the start of the year. Two days after Palmer won the Masters, Mercer Bailey of the Associated Press wrote that Palmer "has charted a course which could carry him to the biggest grand slam in golf since Bobby Jones' feat in 1930."

Without a figurative kick in the pants from Drum, Palmer might not have won his second straight major. "They were very close," M.J. says of Bob's relationship with Palmer, "and Bob ragged him to death." Eating hamburgers in the locker room with Drum, Jenkins and a couple of players between the third and fourth rounds of the U.S. Open at Cherry Hills, Palmer, who trailed Mike Souchak by seven shots, wondered if a closing 65 would do him any good. Drum dismissed the prospect as only he could.

"It really pissed me off, to tell you the truth," Palmer says. "When I asked him what he thought 65 would do for me, he got kind of sassy like an old friend would, particularly when another friend of his, Souchak, was leading me by seven shots. The more he talked, the madder I got."

Motivated to prove Drum wrong, Palmer drove the 346-yard par-4 first hole that had flummoxed him for three rounds and two-putted for an easy birdie. He birdied six of the first seven holes and shot 65 to emerge the winner.

"Drum came up with a real snappy lead, something like 'Arnold Palmer wrestled with Cherry Hills for three rounds and then strangled it,' " remembers Giffin, forced to tinker with the beginning of Drum's story after an editor decided it needed a few more facts if it was going to run on the paper's front page. Moreover, on the biggest story Drum would ever write about Palmer, his byline was inadvertently left off.

DENVER, June 18 --Arnold Palmer, who had wrestled with the Cherry Hills golf course for three rounds, caught it in a stranglehold on the final 18 today and pulled off one of the most unbelievable victories in National Open history.

Drum soon made an important point.

The sensational victory moved him over the second hurdle in his bid for present-day golf's Grand Slam.

The idea of some sort of "Grand Slam" to supplant Jones' singular sweep of the U.S. and British Opens and Amateurs in 1930 had percolated sporadically since 1949. By then the Masters was gaining popularity and prestige among players and the public, and after Sam Snead won at Augusta and took the PGA (then played in May), interest was building. Heading into the U.S. Open at Medinah—where Snead would lose a heartbreaker to Cary Middlecoff -- Will Grimsley of the AP wrote that a win would give Snead "a professional sweep comparable … with amateur Bobby Jones' grand slam of 1930."

By 1960 it was possible for a golfer to compete in all four pro majors, which hadn't been the case in 1953 when Ben Hogan won his "Triple Crown" (Masters, U.S. Open, British Open) because the PGA overlapped with the British. Palmer remembered Drum on their transatlantic flight to Europe after the U.S. Open (Drum recalled it as being on the Denver-New York leg) affirming his belief that he was striving for a new achievement, a "modern" Grand Slam.

Drum talked up Palmer's plan in Ireland, where the latter was teaming with Snead in the Canada Cup en route to St. Andrews, and at the Open where Palmer lost narrowly to Kel Nagle. Although Palmer couldn't attain the slam, it would forever be modern golf's holy grail.

Eager for new challenges, Drum left the Press in 1963. For two decades he did freelance stories and held several golf marketing and p.r. posts, including in Pinehurst, N.C., where he settled. "[Fellow writer] Charley Price once said that he would have gotten me a job, but he didn't know what kind of work I was out of," Drum told the Toledo Blade in 1987.

Drum remained a familiar presence through the years, a regular at the Golf Writers Association of America annual tournament in Myrtle Beach, where he would emcee the dinner with the aplomb of an acerbic comedian. "He was really funny and totally irreverent," says retired Charlotte sports columnist Ron Green Sr. Once, upset with another writer at the GWAA event, Drum smashed a windshield with a golf club. "He quit drinking for long periods," says Kevin. "He grew up in the martini and high-ball era. That's just the way it was. I don't think he'd change a thing about his life."

Drum certainly wouldn't rewrite what happened to him when he was 66. He had long been a part of the CBS Television golf entourage as a writer, thanks to the generosity of producer Frank Chirkinian. In the summer of 1984, encouraged by a young producer named David Winner, Drum took his curmudgeonly act to CBS' golf coverage with three-minute features called "The Drummer's Beat."

"Lemme tell you something," he said to the Miami Herald in 1985, "I've been doing what I'm doing for 20 years in bars across America. Now, I'm getting paaaaaid for it."

"It never really mattered what the piece was about," Winner says. "What people remembered was the Drummer." Drum was nominated for a Sports Emmy in 1987, losing to ABC's Dick Schaap. "I think it made his life, and I also saw how disappointed he was when it all kind of came to an end [in 1988]." CBS didn't pinpoint why it ended Drum's segments but among his friends, there was speculation he had rubbed the right CBS executive the wrong way.

Drum's health declined in the 1990s, but he managed to make final journeys to the 1995 British Open and the 1996 Masters. He passed away May 8, 1996, of heart failure. "He died so gently," M.J. told Pittsburgh writer Marino Parascenzo. "So easy, so gentle, and that made me grateful. God knows, he sure didn't live easy and gentle."

One morning during the 1997 Masters, Drum's two sons hustled down to the 13th hole. "It was a caper," says Bob Jr. "We slipped out there and spread some of his ashes in the azaleas by the green. We said some prayers and we cried a little. Then we thought it would be great to have a beer. Dad would want us to have a beer. So we went to a concession stand and had a beer."