News

Shot No. 2,889

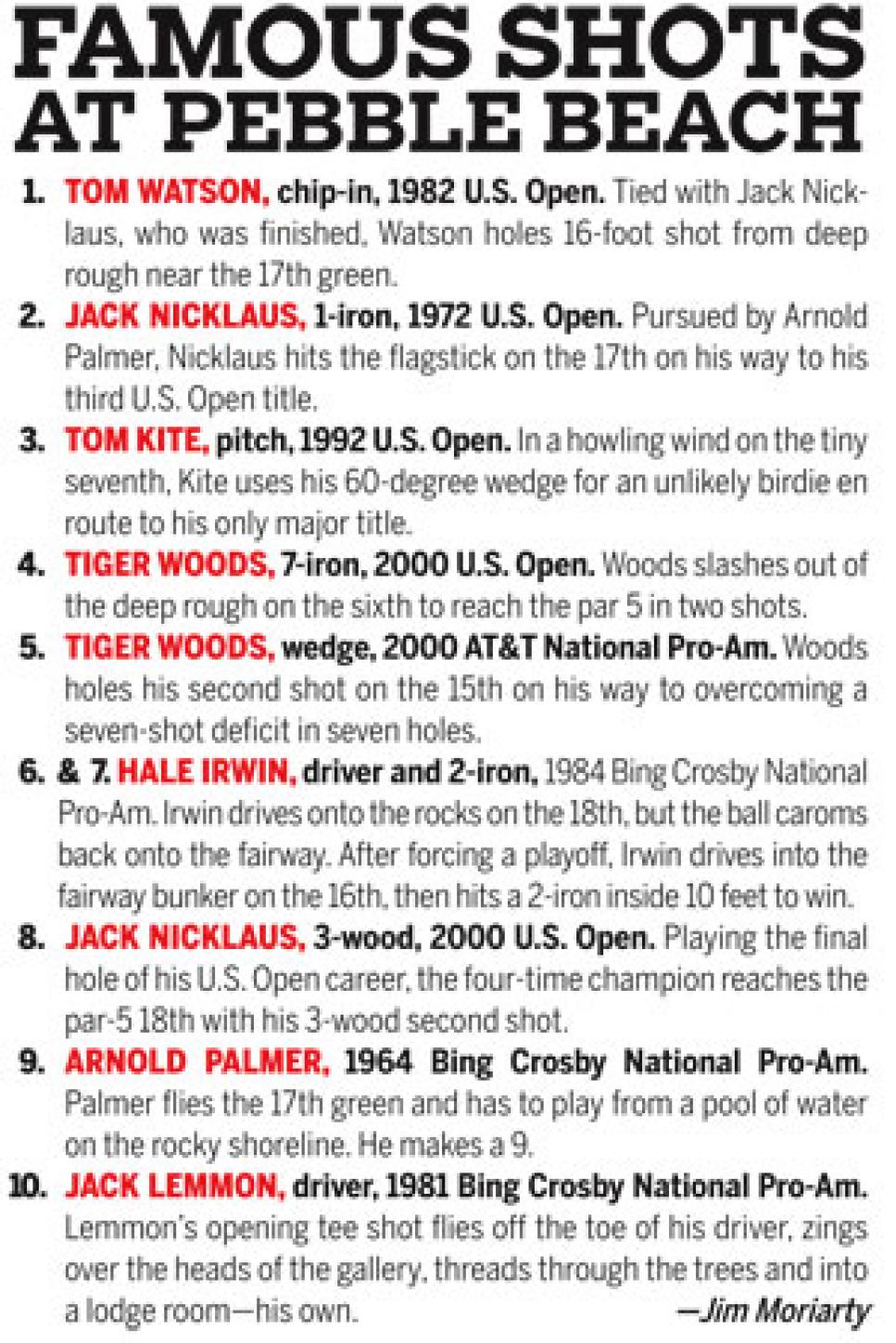

Chipping away at history: With a chance to win the championship he wanted most, Watson produced a shot for the ages from a difficult lie on the 71st hole.

The shot took only a couple of seconds, but it had been years in the making.

Tom Watson had literally been schooled in the U.S. Open. His father, Raymond, a handy golfer himself, knew the championship chapter and verse. He could name its winners, the year they won and how they won, going back to 1895. "The Open became the pinnacle for me as well," Tom says, "very simply because it was the toughest tournament to win."

But by 1982, Ray Watson's encyclopedic roll call did not yet include the name he most wanted to recite. Not that his son hadn't had his chances. Tom challenged futilely at Winged Foot and Medinah, Cherry Hills and Baltusrol, all the while stockpiling claret jugs, green jackets and assorted PGA Tour titles that made him the best player of his generation. To get what he wanted most, however, Watson would have to beat the best player of all time.

He had done it before, of course, outdueling Nicklaus at Turnberry and outlasting him at Augusta National in 1977. But in a U.S. Open? At Pebble Beach? "The Open is more important than any other tournament," Watson said then. "To be a complete golfer, you have to win the Open." In 1982 Nicklaus wanted a fifth Open; Watson needed his first.

As he stood on the 17th tee, emerald grass under foot and a gray sea in the distance, it was approaching 5 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time on Sunday, June 20, 1982. Watson was tied for the U.S. Open lead with Nicklaus, who was three groups ahead. After a frenetic charge earlier in the day that brought him toward the top of the leader board, Nicklaus had finished uncharacteristically, missing birdie putts on Nos. 16, 17 and 18. Despite leaving the door ajar, Nicklaus was confident. "Even though I missed those putts, I still thought I was going to win the tournament," Nicklaus says nearly three decades later.

Playing with Watson in the final group, Bill Rogers, the slightly built 1981 British Open champion, had the honor at 17. With its history of tripping up golfers -- although Nicklaus' glorious 1-iron off the flagstick wrapped up the 1972 U.S. Open for him, his final-round bogey there kept him out of a playoff for the 1977 PGA Championship -- it was no surprise the par 3 was playing as the hardest hole in the final round. It measured 209 yards, only a few paces from its longest yardage, with the hole tucked as far back and left as possible.

"It was a very hard hole, just as it had been in 1972," says Frank Hannigan, then senior executive director of the USGA, who was supplying rules commentary for ABC that week and positioned at the 17th hole on Sunday. "It was a long iron into a small target, and it was chilly."

After watching Rogers hit a fairway wood, Watson studied the shot with his longtime caddie, Bruce Edwards, who wanted this one as badly as his boss -- he hadn't been on the bag for Watson's five previous major conquests because Watson hired Alfie Fyles at the British Open and a local caddie, per club rules, at the Masters. Edwards knew better than anyone the uphill U.S. Open road Watson had traversed, and as recently as two days earlier, it looked as though this would be another lost weekend. Watson's second-round even-par 72 easily could have been 10 strokes higher; he hit only five fairways, and that's usually a felony in a U.S. Open.

"I was hitting it awful," Watson remembers. "I gave myself no chance to win the tournament at the beginning of the week. I was hitting it so far sideways that I was in the galleries where they walked the grass down, so I wasn't stuck."

During a long practice session following the second round, Watson hit on something. He thought his wild driving was due to the separation between his arms and upper body on his backswing. If he could keep his arms more in sync with his body, he might restore his accuracy. After drilling a few drivers, he said quietly to Edwards, "I've got it."

On the 71st hole, in the damp air with a fresh breeze off Carmel Bay, Watson and Edwards debated between a 2- and a 3-iron, Edwards lobbying for the latter because he thought the harder Watson swung the better he played. Watson, though, was concerned about carrying the large left-front bunker. The downside of the 2-iron was that, fueled by a bit of major-championship adrenaline, it potentially could leave him long, left and in big trouble.

Watson opted for the 2-iron, aiming at the point where the left and right portions of the small, hourglass-shaped green meet. He made his brisk, upright swing. He hit it very well, but "hooked it too much." As the ball took flight, he quickly barked "Down!" Watson and Edwards watched helplessly as the Golden Ram No. 1 drifted left and scooted through the green into deep, wiry fescue. If his lie was as poor as could be expected, Watson's dream of a U.S. Open title would be dashed. As player and caddie headed for the green, Watson mumbled grimly to Edwards, "That's dead."

Hannigan recalls holding out hope, however slim, for Watson's chances. "Remember," he says, "Watson was what Seve was around the greens and what Tiger is now. So, I thought he had a 50-50 chance of making 3."

As Watson sized up his 16-foot chip, many others were less optimistic about his predicament. A few minutes after Watson missed the 17th green, Terry Jastrow, who was directing the telecast for ABC, dispatched Jack Whitaker to interview Nicklaus in the scoring tent near the 18th green. Also in the tent: a young USGA staffer named David Fay, who was calmly watching the tableau unfold before him both live and on a television monitor. Fay had completed his task of introducing the contestants on the first tee and spent the afternoon at No. 18.

"We're all watching the telecast, and we all see where Watson's ball goes," says Fay. "Jack's beaming, feeling really good at that point...Jack Whitaker turns to Jack Nicklaus, and they're chatting, and no one's really watching the monitor, except me."

As Watson, in his dark blue Fila-logoed sweater, bluish-gray slacks and coffee-colored spikes clambered toward the green, Edwards preempted the gloomy conclusion that Watson and most everybody had reached. "Bruce said, 'Hey, let's see what kind of lie we have,' " recalls Watson. " 'We can still get it up and down.' "

It must have seemed like empty encouragement from a good friend, but as the duo drew closer to the ball, Watson felt better. "I could see some ball, so the lie didn't look too bad, and even though it was in the deep grass, I still had some room underneath the ball," he says. "I could get the clubface underneath." At that moment, Watson says, he went from thinking "dead" to thinking "life support."

got to celebrate a major title with Watson for the first time.

Though far from perfect, the lie may have been the biggest and most important break of Watson's career. In fact, had this been the Crosby, when the wintertime rough is minimal, his ball almost certainly would have ended up on the beach. But despite the good fortune, the situation still called for extreme touch. "I still had a formidable shot," Watson says, "off a downslope trying to hit a high, lofted shot about four feet in the air -- as high and soft as I could hit it -- and have it land softly enough where it didn't run by 10 or 15 feet."

While Watson studied the chip, Nicklaus was interviewed live by Whitaker, who all but handed Jack the trophy. Before sending the action back to 17, the typically unflappable veteran broadcaster, appearing for the first time on an ABC golf telecast, said to Nicklaus, "It's a pleasure to be in your time." The sentiment and the terminology were awkward, but they clearly reflected the sense, now permeating the TV crew, that Nicklaus had already won.

"We all thought he [Nicklaus] had done it," Jastrow says. "When Whitaker did the interview with him to the left of the 18th hole, it was more or less a winner's interview."

Written off or not, Watson was the last man standing, and he was as prepared as anyone could be for what he faced. During U.S. Open weeks, he imagined the worst lies a USGA setup could produce and practiced them religiously. Ironically, that week at Pebble Beach, because his long game was shaky, he was even more diligent about practicing shots from deep greenside rough. "I practiced that shot all the time, knowing that I was hitting the ball really poorly and knowing that I was going to be faced with that particular shot," he says.

Edwards believed Watson, despite his skill and having gotten a decent lie, still would be lucky to stop the ball fewer than 10 feet past the hole.

"Get it close," Edwards told him.

"Get it close?" Watson answered. "I'm gonna make it!"

"I said it more out of just trying to get myself ready to play the shot than anything else, [to] mentally play the shot," Watson says, "but when I got up over the ball, I knew what I had to do."

It was Watson's 2,889th shot in U.S. Open competition, and he wasted little time. Watson was using a 56-degree Wilson Staff Dyna-Power sand wedge he had salvaged a few years earlier from David Graham's garage. "David loves golf clubs, and he had only the best," Watson says. "His castaways were anybody else's first-teamers."

After a swing as purposeful as it was abbreviated, Watson's ball came out as high and soft as human nerves would allow. As it began to trundle over the putting surface, announcer Dave Marr eyed its every rotation. "It looks good, it looks good," Marr said in a voice rising with possibility. Soon enough, the ball began to accept the slight rightward break. Just before it collided with the flagstick, Watson crouched into a hunch of hope and anticipation, and as the ball fell into golf lore, an incredulous Marr asked his audience, "Do you believe it? Do you believe it?"

The ordinarily understated Watson shed a decade of trial and frustration, his exultant jog onto the green giving photographers fits as they tried to keep his jubilant figure in focus in the dim light. Watson turned and pointed to Edwards. "I told you!" he said. "I told you I was gonna make it!"

While the earth heaved, Rogers stood stunned, motionless and smiling on the edge of the green. This was not the first time he had experienced Watson's short-game brilliance. In fact, two years earlier, at the Byron Nelson Golf Classic, Watson chipped in on the 71st hole to deprive Rogers of victory. "I've seen him do a lot of remarkable things, but 17 [at Pebble] was shocking," Rogers said years later. "That birdie put me in absolute shock -- I'll remember it all my life."

If it was a shock to Rogers, it was a mugging of Nicklaus, about to be taken down once more by his younger rival. Neither Nicklaus nor Whitaker was watching the TV monitor when Watson hit his second shot at the 17th, but Fay, who would go on to become the USGA's executive director, was watching. When Watson chipped in, Fay blurted out, "Holy [bleep]! He holed it!"

Nicklaus, seated in a swivel chair, spun around, looked at Fay and said, "No, he didn't."

Fay pointed to the black and white monitor. "Look."

According to Fay, all expression drained from Nicklaus' face as he stared at the screen. "I can't believe it," Nicklaus said to no one in particular. "I can't believe it happened again."

"For a moment he was ashen," Fay recalls, "but he quickly regrouped and he was Jack Nicklaus again, the most gracious loser the game has ever seen."

Watson didn't have to birdie the 18th hole, but when he did Nicklaus was there to greet him. The two friends shook hands and, according to Watson, Nicklaus told him affectionately, "You little son of a bitch, you did it to me again. I'm proud of you." As they walked off the green, Nicklaus put his arm around Watson. Watson smiled and reciprocated, the duo reprising the après-golf pose at The Duel In The Sun.

"If it takes me the rest of my life, I'm gonna get you one of these times," Nicklaus teasingly said to Watson during the trophy ceremony. But the light had gone out of one of the game's greatest rivalries. Each man would have other Grand Slam victories -- Watson at the 1982 and 1983 British Opens, Nicklaus at the 1986 Masters -- but they would never finish one-two again in a major championship.

What's left of the shot? Millions of memories, a grainy videotape of probably the most replayed shot in golf history, an old club that rests in a display case outside the pro shop at The Greenbrier, where Watson is professional emeritus. "The Wedge, 1982 U.S. Open," is all it says, is all it has to say.

The ball Watson holed out on the 17th never made it off the Monterey Peninsula. "I gave it to the ocean," says Watson, who impulsively threw it into Carmel Bay after winning. "It was kind enough not to swallow up any of my golf balls, so I gave it that one."

And he made a call that evening, Father's Day, to Ray Watson, whose love of the U.S. Open was now deeper than ever.