News

"Yes SIR!"

As he got to the ninth hole at Augusta National GC on a Kodachrome Sunday afternoon, Jack Nicklaus, five green jackets or not, was a bit player in the 1986 Masters. He had begun the final round four strokes behind and nothing had happened to perk him up. Nicklaus was 46, had played poorly so far that season while trying to right an unwieldy business empire and was six years removed from his last major championship victory. After watching Nicklaus struggle earlier in the week, CBS analyst Ken Venturi told USA Today, "Jack's got to start thinking about when it is time to retire."

Venturi's boss, Frank Chirkinian, the legendary and longtime coordinating producer of CBS' Masters telecasts, loved it when Nicklaus starred in one of his shows, but the Golden Bear wasn't a factor this time. Chirkinian was the ultimate realist, not in the business of telling fairy tales.

At No. 9, Nicklaus faced an 11-footer from the right fringe for birdie. Twice, just as he settled over the ball, roars from elsewhere on the course, jubilation for someone younger and stronger, caused him to back off. Nicklaus turned to the gallery and said, "Let's see if we can't make that same kind of noise here." Nicklaus made the putt. It could have ended there, a sweet moment for an aging icon and his loyal fans. Beyond those spectators ringing the ninth green, few took notice. Except for Lance Barrow.

Barrow was a 31-year-old associate director at CBS Sports with various responsibilities at the Masters, none more important than capturing and cueing up replays, so if Chirkinian decided a shot was important enough to show on tape, Barrow had it handy.

The protégé felt compelled to advise his boss of Nicklaus' stirring. Feeding the cantankerous Chirkinian tidbits was like feeding a shark -- things could go badly -- but Barrow pressed ahead. Barrow was seated only a few feet to Chirkinian's left in the sun-starved production truck, lit by the blue haze of some 60 television monitors. "Frank," said Barrow, "we've got Nicklaus with a birdie at nine."

Predictably, the boss was dismissive. "I don't need him," Chirkinian snapped. Nicklaus proceeded to birdie No. 10 with a 25-foot bomb. The husky, intrepid Barrow, nicknamed "Buddha" by Chirkinian, again tapped his boss on the leg. "We've got Nicklaus with a birdie at 10, Frank."

"I don't need him," growled Chirkinian. "Quit telling me about Jack! Nicklaus means nothing in this golf tournament!" Then came the dressing down, Chirkinian's bread and butter. "Buddha, if you don't learn what drama's all about, I'm going to send you to drama school so you can learn it. Leave me alone. Jack Nicklaus is not a part of this tournament!"

When Nicklaus birdied the 11th hole, Barrow again summoned his nerve. He gently tapped his mentor on the leg and said, "Frank, uh, I know that Jack means nothing to this golf tournament, but he just birdied 11 … and he's two off the lead."

Chirkinian glanced at Barrow and said, "Cue it up, Buddha."

Six holes ahead, Verne Lundquist was sitting in the tower behind the 17th green. A beefy, friendly man, Lundquist was already an accomplished broadcaster. For 16 years he had been the sports anchor at WFAA in Dallas. His work covering the dominant Dallas Cowboys teams of the 1970s had brought him to the attention of ABC Sports, which he joined in 1974. Eight years later Lundquist went to CBS, working mostly football and basketball, and by 1983 he was added to the network's Masters announce team.

The son of a minister, born in Duluth, Minn., and raised for a time in Everett, Wash., and then Austin (he considers himself a Texan), Lundquist gravitated to communication arts from childhood. Having seen his father speak coolly from the pulpit each Sunday,

Lundquist was drawn to and comfortable on the stage. And then there was his voice, a distinctive baritone that delivers smooth, even portions. If gravy could speak, it would sound like Lundquist.

Like any good Texan, Lundquist grew up with an appetite for sports, but his size -- 5-foot-4 as a high school sophomore -- precluded a career on the field. "My way to compensate for that was to write and to talk," he says. "I loved writing. Still do."

Lundquist didn't play golf until he was 31, and he might not have started if it hadn't been for Rives McBee. A well-known Texas golfer, McBee had recently quit the PGA Tour to become head professional at Las Colinas, when he phoned Lundquist at WFAA and posed a question. "Do you ever want to do golf for ABC?" Lundquist assured McBee he did. "Well, then you better learn how to play." Early on McBee asked his new student, "What are you going to do if somebody hits a provisional?"

Lundquist was blank.

"Do you know what a provisional is?"

"No, not really."

"Well, you better be prepared," insisted McBee, who explained the procedure. A short time later Lundquist was assigned to cover the Byron Nelson Golf Classic on radio. Minutes into the broadcast Bob Dickson stood on the 10th tee at Preston Trail and duck-hooked a ball out of play. "I proudly said over the air, 'Looks to me like he's going to have to hit a provisional,' " says Lundquist. "Rives heard it, and he loved it."

The education of Merton Laverne Lundquist paid off. He not only became a lover of the game (unrequited by the way), but just a few years later, in 1976, he got the call for network golf coverage. In February of that year, ABC Sports was contracted to air both the Olympic Winter Games and the Hawaiian Open. With most of its brand-name announcers in Austria, ABC pulled Lundquist off the bench and assigned him to cover a group that featured Lee Trevino. This seemed a fortuitous break, as Trevino, a Metroplex resident, would surely see Lundquist as a familiar face.

"How perfect is this," thought Lundquist at the time. "He's from Dallas. He'll come over and chat. I'll be the bright shining bulb on the Saturday afternoon telecast." Trevino started six shots back and never got on the air. Neither did Lundquist, not a syllable. After the telecast ABC producer Terry Jastrow approached Lundquist, put his arm around him and said, "Verne, I'm not sure if you've looked at your contract very closely, but you should. It says in there that you get paid by the word."

Lundquist's first golf tournament for CBS was the 1983 Phoenix Open. He thought it might be a good idea to arrive early and introduce himself to his new boss. He found his way to the CBS Sports compound, a maze of trailers, cables and cold coffee that looked like the back lot at a summer carnival, and asked to see Frank Chirkinian. As he entered the producer's lair, Lundquist did what any well-bred, mild-mannered minister's son would do. "I said 'Hi, Frank. I'm Verne Lundquist." Chirkinian replied, "I know who the ---- you are. Who the ---- do you think hired you?"

The small talk over, Chirkinian quickly oriented his new employee. "I've got three rules," he growled. "If you follow these three rules we're going to get along just great. Number One: Don't ever say your name on television. Nobody gives a crap who you are, OK? And I hate this 'Thank you, Frank,' 'OK, Pat,' 'Yes, Ben' stuff. Just do the golf. Don't give me your name.

"Number Two: Don't you ever dare talk over a swing. Whatever brilliant commentary you have to add to the totality of this telecast you better wrap it up by the time the club starts going back, and you better not say anything else until the ball lands.

"And Number Three, and most prominent: Don't you state the obvious. We've got 65 technicians out here with cameras and microphones and graphics machines. They'll show what's going on. You're a headline writer. You tell me something that I don't know or can't see."

A tragedy had landed Lundquist in the 17th-hole tower in 1986. Frank Glieber, one of Lundquist's dear friends, had called the action at No. 17 since 1968. Upon Glieber's death from a heart attack in May 1985, Lundquist, whose first Masters assignment was at the 13th hole in 1983, was reassigned. Although the penultimate hole at Augusta National had been the scene of pivotal final-round strokes before -- including Bernhard Langer, just the previous year -- it was about to see a new dimension.

Nicklaus was growing younger and blonder with each passing hole on the second nine. After a bogey at 12, he bounded back with a birdie-par combo at 13 and 14. His Richter-scale eagle at 15 and pine-rattling birdie at 16 made it clear that the audio portion of this story was about to fall on the vocal chords of a guy who started his career as a $1.05-an-hour weekend deejay in Seguin, Texas.

The drama of the 17th hole began inauspiciously for both Nicklaus and CBS. After Seve Ballesteros dunked his second shot at 15 in the water, the truck sent viewers to 17, where Nicklaus was preparing to tee off amid murmurs from nearby 15. "I heard this ugly sound," said Nicklaus. "I knew exactly what it was. I knew that Ballesteros had hit his ball in the water. I hate that sound because half of the sound is cheering for me, which I don't like when somebody makes a mistake, and the other half was the groan for Seve who hit it in the water."

Twenty-five years later, it seems odd that such a monumental moment was covered live by a camera positioned 400 yards away, behind the green. Not only was the distant view clumsy, but the dappled sunlight mixed with the steep incline from shaded tee box to sunlit green to create a cameraman's nightmare. After Nicklaus hit his tee shot at 17, the ball quickly exited the frame. The viewer never had a chance. The groans -- of Nicklaus and the gallery -- are picked up on the audio, but the camera manically pans the fairway to no avail. Like viewers at home, the newcomer to the 17th tower had nothing to work with.

"We're still searching," Lundquist said. "It's not good whatever." This lost shot still raises hackles among CBSers.

Although every staffer contacted now downplays the snafu, not one would explain precisely what went wrong. When Chirkinian, known for his martial command of a production, was asked if he'd been raging in the truck, he tried to shrug it off. "We never went crazy in the truck," he said. "Somebody might've gotten a mild chewing out, but nobody went crazy. Never lost control. We found [the ball] eventually, that's the good thing."

The good news for Nicklaus was that even though his drive settled close to No. 7 green and was framed by two loblolly pines, he had a clear shot awaiting. Jim Nantz, who was covering his first Masters from the tower at 16, sent ahead to 17 for an update from Lundquist on Jack's prodigal ball. "... Jack pulled his tee shot to left, and they are moving the gallery out of the way. We are told that he does have a clean shot to the green. One hundred twenty-five yards. One heck of a break."

By the time Nicklaus was ready to play his scrambling approach into 17, Seve had bogeyed 15 and, as the screen graphic so clearly displayed, Nicklaus was now co-leader at eight under par.

Lundquist's call of the second shot was sparse, as though he was pacing himself and the viewer.

"... the old bear is oblivious to what has just happened back at 15, of course, concentrating on his second shot from in between two pines, 125 yards out." The shot, often overshadowed by the next, was impressive. It was only a wedge, but it was played through a tunnel of curious patrons, over the ropes, around one of those familiar "Cross Way" signs and into a sneaky fast green.

Lundquist's moment had arrived hand-in-hand with Nicklaus'. In a few minutes the two men, roughly the same age, working pros since the early 1960s, would intersect at history. As CBS cut to Ballesteros playing his tee shot at 16. Lundquist anxiously waited.

"I'm sitting there watching Jack Nicklaus playing the 71st hole of Augusta National at 46 years of age with his son on the bag," says Lundquist, "and I did think to myself, 'Keep it simple.' I thought about Chirkinian: 'Stay out of the way.' And then I thought to myself: 'For God's sake, don't screw this up.' "

The man who was born with a pastor's oratory, who is married to a singer and who loves classical music, tuned up. He found a lower octave and a slower, breathier release. The reasons were both practical and theatrical. "We all laugh about the golf announcer's voice," Lundquist says. "A lot of people don't understand why we have to whisper. Primarily, it's because the players can hear us."

But when Lundquist lowered his vocal instrument in prologue to Nicklaus' birdie putt at 17, he was also building drama. "I do bring it down," he says. "Make it appropriate to the moment."

In the tower with Lundquist were George (Hulk) Rothweiler, a veteran CBS camera operator, and Neal Pilson, then president of CBS Sports. Two additional cameramen were on the ground, most notably Bill Murphy, in what CBS calls the flanker position, shooting the action from the side of a hole. Murphy, who settled into position at the far right edge of the green looking past the hole to a studious Nicklaus, was about to capture golf's joyful rejoinder to the Zapruder film.

Ask Lundquist to name the announcers who influenced him and the list, which includes, football commentating legend Ray Scott and CBS stalwart Pat Summerall, is peppered with reluctant talkers. Scott's trademark call, dating to the glory days of the Vince Lombardi-led Green Bay Packers, speaks volumes about Lundquist's inclination toward brevity: "Starr, Dowler, Touchdown."

"He may have been the best ever at keeping it simple," Lundquist says. Brevity. Experience. Expertise and a voice that can make a La-Z-Boy recline. It all came together that Sunday afternoon like pimento and cheese.

When time came for the coup de grâce Lundquist chose not to rely on his television monitor but on his own eyes and the scene unfolding immediately in front of him, Nicklaus putting from Lundquist's right to left.

Chirkinian steered the action from Ballesteros' nearly beached ball on 16 to Nicklaus at 17 green, crouched and surveying the line with son, Jackie. The ensuing tableau would run almost two full minutes, an eternity in the snapshot world of live golf. "It's got to go right," Jackie said. "I know it's going to go right," said father to son, "but I think it's going to come back left at the hole. Rae's Creek is going to have an influence at the end." Murphy supplied his flanker view from the right side of the green. Lundquist: "Jack Nicklaus has looked over this birdie opportunity from about 18 feet (pause). Go back 11 years to 1975, and Nicklaus and that terrific tournament with Tom Weiskopf and Johnny Miller; replace the names for 1986 with Ballesteros and Kite, and it's remarkably reminiscent."

Quartering shot, from right rear, of Nicklaus in extreme close-up as he began to settle over the ball. Lundquist: "And here's the constant." Complete silence for 10 seconds. "This is for sole possession of the lead."

The truck returns to Murphy's long shot from across the green. He's about to shoot a sequence that would make the Sabols, curators of NFL glory, cry. Count slowly to 12. One Mississippi, Two Mississippi ... As Nicklaus calculated the line, figured the speed and did whatever else great putters do in their heads, Lundquist was mute for an agonizing 12 seconds. Talk about call waiting. That much dead air gets weekend deejays fired, but it makes the difference between a call and a moment.

"I was taught pretty well by Frank, and I took those lessons to heart," Lundquist says. "As soon as I said 'This is for sole possession of the lead', it's a visual medium. Don't need to say anything else."

Forty-nine seconds into Scene 17, Nicklaus makes contact with his oversize Response putter. Two seconds later, Lundquist, steady and with a discernible hint of optimism: "Maybe …"

"I'd say this not as a broadcaster but as a fan: I hoped he would make it, and I don't know how, in that moment, you truly separate," he confesses. "I know what we're all supposed to say, 'I'm only there to report, I don't really care,' but I had kind of become invested in his story, I think we all had at that point." Ya think?

Nicklaus stepped toward the hole with his left foot.

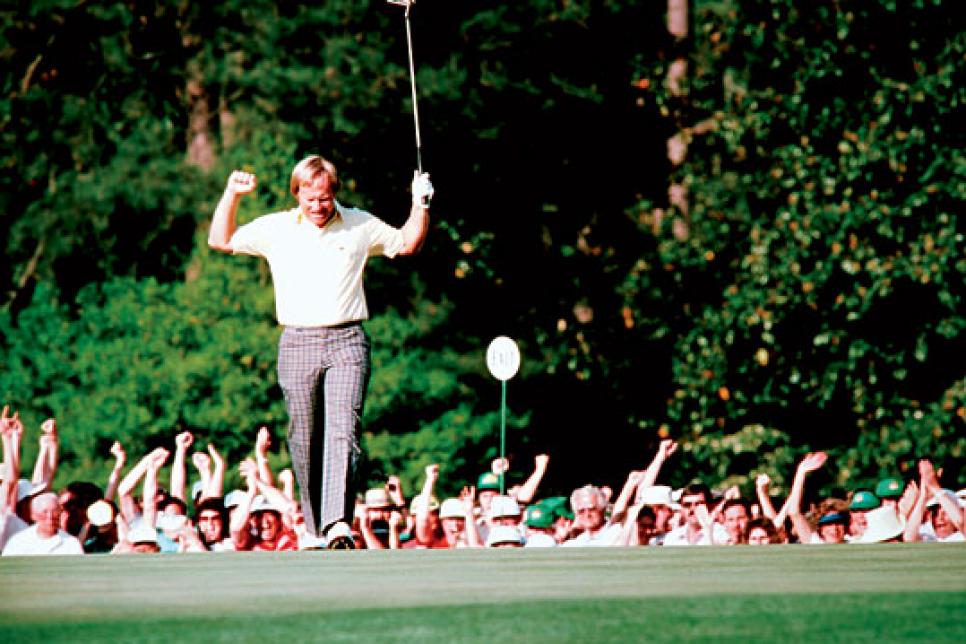

Fifty-four seconds in, the ball eked right, steadied its course, acceded to the dictates of history and ducked its head from the thunderous wave. "… Yes SIR!"

Punctuation was supplied by a raised putter and 6.4 million spilled beers. Not only was there the undiluted drama but a cinematic quality rare for a live broadcast. Live TV can be a jungle -- viewers never got to see Nicklaus' long putt go in the hole at No. 16 in the 1975 Masters because his caddie, Willie Peterson, stepped in front of a camera at the moment of truth -- but nothing distracted from the grandeur at the 17th green. "It was a perfect storm," says Barrow. "There are a thousand things in that moment that could have gone wrong." None did. The rhythmic timing of Lundquist's words; their synchronicity with Nicklaus' step and jab; the oral and visual eruption of the crowd. Viewers at home had the best seat in the house. The entire line of the putt was unblocked by shadow or hillock. The late-afternoon light was golden, setting off a gauzy aura around the protagonist. Lundquist knew to let the tableau play out unadorned. No soundtrack necessary. Nicklaus briefly looked mortal when, after re-ordering the universe from about 11 feet, he sighed upward in relief, but he quickly morphed into half-man half-race horse, champing at the bit, sweating like a thoroughbred and twitching at the prospect of one more lap.

It's safe to say that a top-shelf Hollywood film crew would require dozens of takes to accurately re-create what unfolded that unscripted afternoon. "Even then," Barrow says, "maybe it could only be done in an editing suite."

Alone at nine under, Nicklaus was once again a leading man.

Lundquist stood up, took a deep breath and looked down. The first person he saw was Tom Brookshier, Summerall's old friend and NFL broadcast partner, who was there on a CBS credential. Brookshier's hands were clenched in ectasy, high above his head, and he was shaking them like the Bishop in "Caddyshack." Lundquist said to Brookshier, "Tommy, wasn't that greatest thing you ever saw?" Brookshier responded gleefully, "I'VE GOT HIM IN THE CALCUTTA!"

It was Woodstock for the khaki and loafers set, but there were still two contenders who could muck up destiny. Not for another hour or so, after Tom Kite and Greg Norman finally came up short, did Lundquist realize he had taken a giant step toward broadcasting immortality.

In previous years calling the Masters, Lundquist would have been on the road as soon as the last group had finished his hole. His habit was to hop in his rental car and zip to Hartsfield Airport to catch a 9:50 flight to Denver and head from there to the home he shares with his wife Nancy in Steamboat Springs. This day, however, Lundquist stayed in the tower to watch the finale: The hugs, the tears, Kite failing to birdie the 18th hole, Norman failing to par it. Afterward, Lundquist drove his golf cart back to the CBS compound.

Inside the production truck Chirkinian, who only a few hours earlier had written Nicklaus off, and Barrow, who had fought to get him airtime, were putting the final touches on their Mona Lisa. "I'm trying to figure out what we're going to do going off the air after the green jacket ceremony, and Frank is showing replays of the moment and everything, and finally he rolls credits," Barrow says. CBS went to "60 Minutes." It was over. Golf's greatest story had been told.

Chirkinian was fond of telling staffers not to "fall in love with your work," but this night was at least marginally different. "Frank got up, tapped me on the shoulder, gave me a nod and walked out of the truck," Barrow says. "To me, that was the biggest thanks he could ever give me. And I don't think we ever talked about it again."

When Lundquist arrived at the compound, he climbed out of the cart and saw Chirkinian. "Frank came over," recalls Lundquist, "and if you know Frank, he's not the demonstrative sort. We called him 'The Ayatollah' with great fear and affection. And he gave me a hug. Yeah, that's when I knew maybe I'd done something nice."