News

How Green-Reading Maps Are Changing The Way People Putt

Dustin Johnson sized up the 17-foot putt for par on the 72nd hole in every possible way. He read it from behind the ball, then from behind the hole, then the side view, crouching at every stop. As Jordan Spieth, the man he shared the lead with, looked on, Johnson took one more look from behind the ball. Nothing to do now but move in and make the stroke, right?

Only it wasn't the final look. In a scene presented to viewers virtually every week, Johnson's caddie and brother, Austin, moved in and opened the folding book that contained a highly detailed map of the green. What they saw clearly gave them pause, because they pointed and conferred for 20 seconds. Finally, one minute and 50 seconds after Johnson had first replaced his ball, he struck the putt. The ball moved left, crept back to the right, then straightened, caught the edge and fell in, eliciting a rare air-punch from Johnson. He went on to win the 2017 Northern Trust FedEx Cup Playoff event and the $1.6 million first prize.

It was a triumph not only for Johnson but for the phenomenon of green-mapping books, and technology in general. The growing proliferation of the maps—it's estimated that as many as 95 percent of PGA Tour players or their caddies use them, and they increasingly are available to amateurs in print and digital form—has spurred great curiosity. People want to know how players use them, the business, distribution and technology behind them, their future and whether they're healthy for the game. They've been present in some semblance of their current form since 2008, but with almost every top player in the world using them—Marc Leishman, who won the BMW Championship, was the only player at the Tour Championship who did not reference one in some way—golfers want to know more.

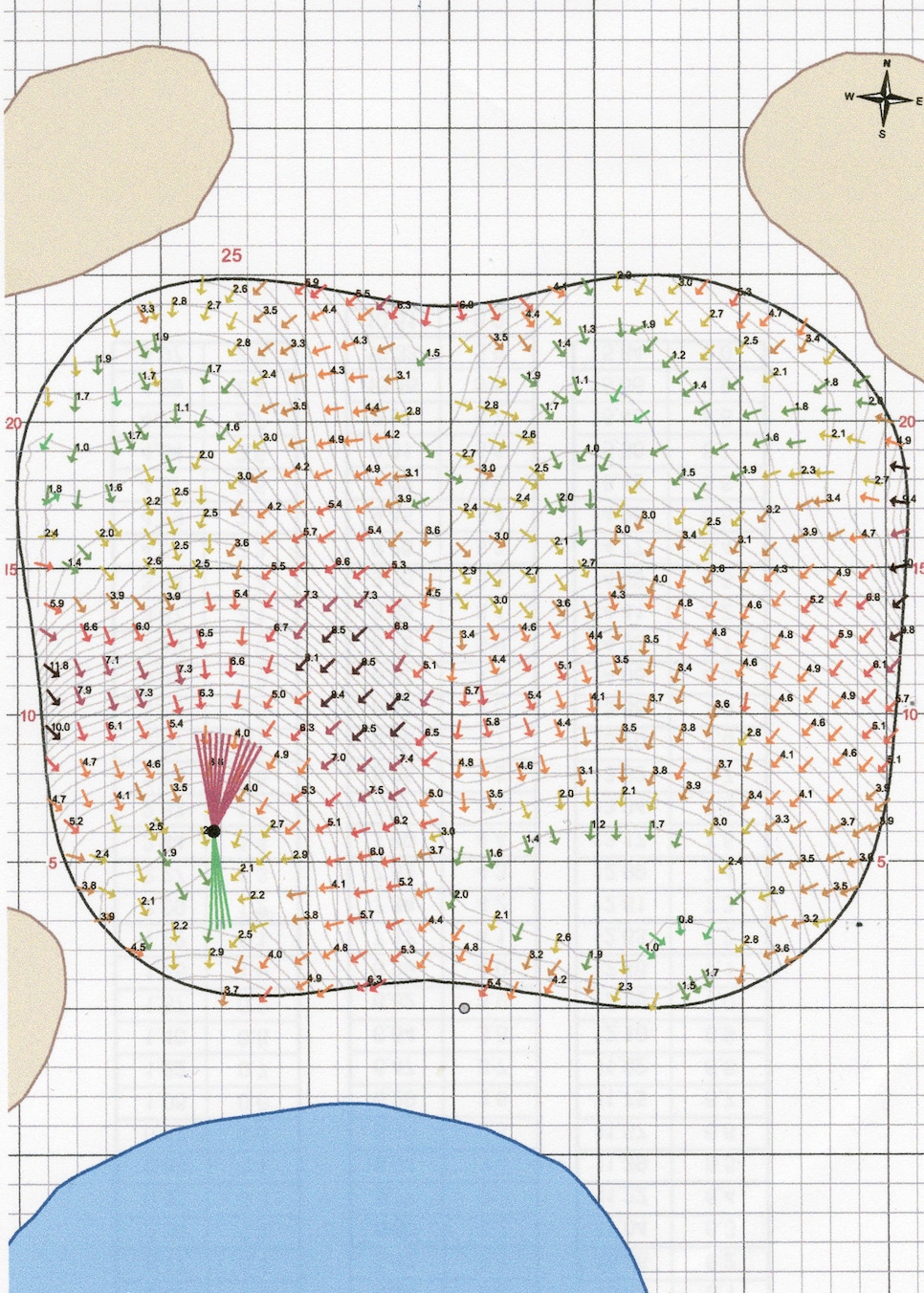

To start, green maps are modern technology at its most advanced, on a par with launch monitors, swing-analysis tools and club and ball technology. The process begins by placing an optical scanning laser directly on or close to the green. Some scanners cost about $120,000 and are used to take impressions of oil rigs, industrial spaces and even car-accident scenes. The unit shoots a laser beam at a mirror that is spinning rapidly within the housing of the device. Millions of beams, reflected by the mirror, are projected onto the landscape of the green, scanning as the device rotates to encompass the entire surface. As each beam is redirected at the green, it is measured precisely. Very precisely. Minute differences in height are measured and fed into storage. Typically, three million to four million bits of data are collected, all in the 10 minutes it takes to scan a green.

"The lasers can easily pick up a small coin from 100 feet away," says Michael Mayerle, president of JMS Geomatics, the company that measures courses for the PGA Tour's ShotLink program. "Discerning green height is well within its capacity. But when we shoot at an area that is on a plane similar to the scanner perched atop a tripod—a sharp falloff at the front of a green, say—we'll move the device and shoot the green from an additional angle."

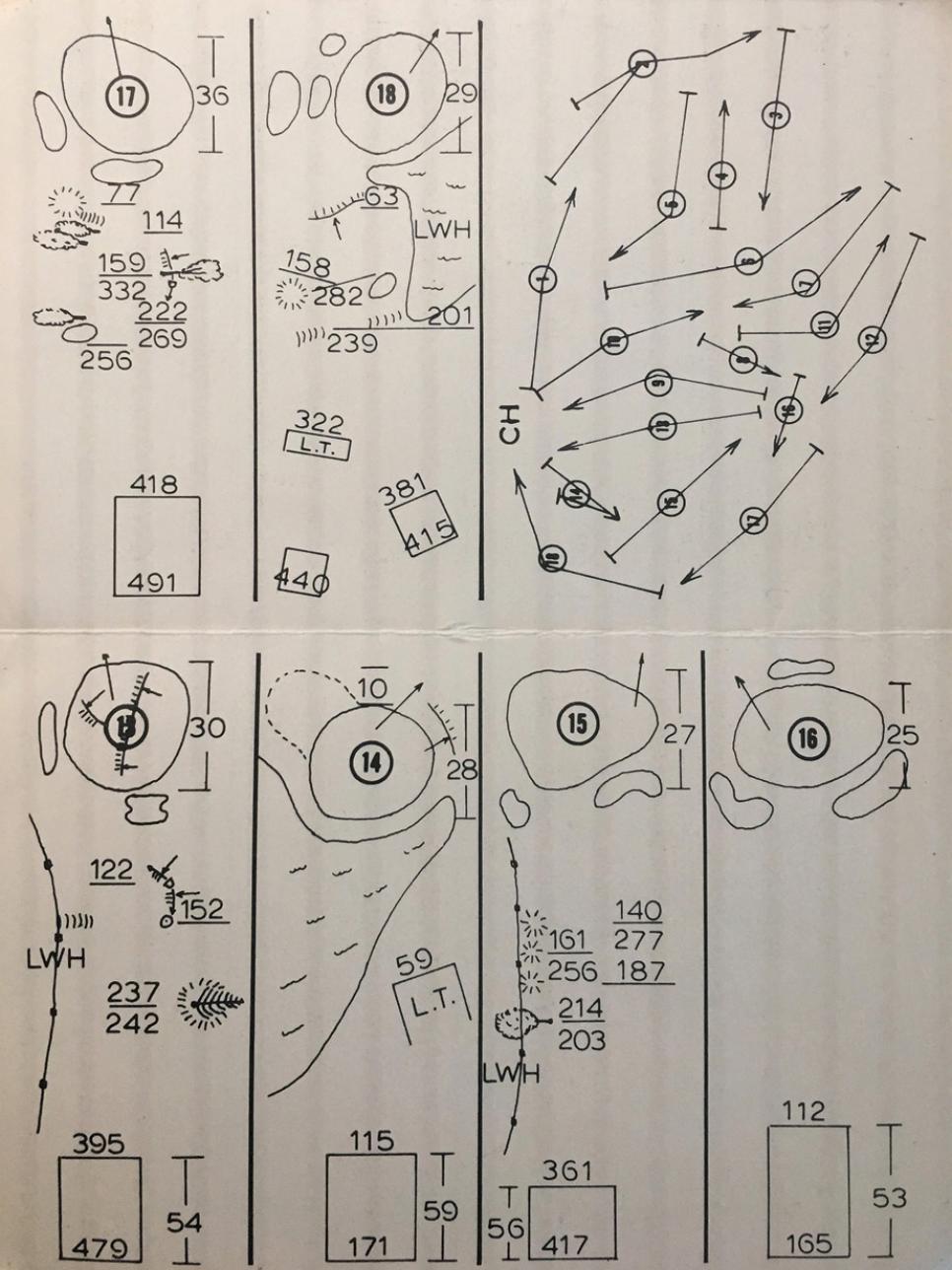

Once the data is collected, it is placed on an electronic template, or outline of the green. Mark Long, for many years the caddie for Fred Funk, is a green-mapping pioneer who has provided maps for the majority of PGA Tour players through his company, Tour Sherpa Inc. (examples are at longyardage.com). Long carefully measures the dimensions of the green using a GPS device, creates the outline, then uses special software to express the laser-scan data as the arrows, contours and sometimes numbers you see on a green map.

"The first green I mapped was at Shinnecock Hills for the 2004 U.S. Open," says Long, 53, who also is the PGA Tour's leading provider of yardage books, including those for most important USGA championships. "At that time, I measured probably 50 locations on each green with a scanner I wouldn't use for that purpose now. Today the data points are in the millions." Long pointed his cursor on a folder containing raw data for a typical green and clicked on "properties." It was nine gigabytes.

Jim Stracka, founder and CEO of StrackaLine, the other leading distributor of green maps for PGA Tour pros and producer of maps for 200 Division I college teams, says the outlines of the greens must be precise for the maps to accurately depict every detail. "On courses such as the ones at Bandon Dunes, there sometimes can be little delineation between the green and the fairway," he says. "In those cases, we'll place balls along the edges of the greens, knowing our laser scanner will offer a sharp contrast along those margins."

NONSTOP JOB: "IT'S NOT A NORMAL LIFE"

Once the data is gathered, the real work of compiling the books begins. Joe Duplantis, who began caddieing on tour in 1998 but now works primarily distributing books for StrackaLine, produces fresh green-map books for as many as 40 tour players five days a week, one for practice and pro-am rounds and one for each tournament round. After retrieving the next day's pin sheets at approximately 8 p.m., Duplantis heads for his hotel room, where he establishes an office that is mind-blowing in scale. "Each week I pack a collapsible desk, four printers, loads of paper and ink, industrial paper cutters and a few other odds and ends," says Duplantis, 44. "One of the most important items is a coffee press, so I won't have to go out."

The work typically goes until 1 a.m. "It can take longer," Duplantis says. "One night I set my alarm for 5 a.m., and when it went off, I was still awake, preparing the books." He is at the course by 5:15 a.m., where he places a book in players' lockers. When players start arriving, Duplantis does bits of follow-up work—billing, gathering orders, taking notes on player preferences, chugging coffee—before going back to the hotel at 11 a.m. to crash. "I sleep in three-hour stints," he says. "It feels like I'm working a ton of half-shifts at 7-Eleven. It's not a normal life. When the calendar year wraps up, I'll have worked 45 tournaments. There's no day off, really, because on Sunday nights, I'm driving my equipment with the car I've leased to the next town."

Long's lifestyle is similarly irregular, though his model is significantly different because of the time he spends keeping his famous yardage books up to date. "I literally haven't taken a full day off in five years," he says. "I love to play, but I haven't played 18 holes since January 2016."

Long's Tour Sherpa green maps have a comfortable lead in sales over StrackaLine. He charges players $150 per week for his books, which are highly accurate but not updated daily. Customization is available, but at a premium. On only a couple of occasions, at a player's request, Long says he has sold a $5,000 green-mapping book that offers a stunning amount of detail. "I really don't want to describe what they show exactly," he says, "but each one took hours to compile." One of Long's selling points is the fact that he updates the dimensions of the greens at tournament sites every year, noting that greens change in size (they usually contract) because of grass encroachment, changes in mowing patterns and sand being blasted onto the surface from bunkers.

StrackaLine charges more: $300 a week. For that, players receive customized books that show in magnified detail the green features in immediate proximity to the hole. Some players want numbers indicating degrees of slope next to their arrows, some do not. Some want their arrows densely packed, or displayed in a wider circumference around the hole. A standard feature the StrackaLine books offers is a series of lines indicating where the straight putts are on every hole. "We show inside-the-hole lines from five, 10, or in the case of Graeme McDowell, even 20 feet," Duplantis says. "We adjust the presentations to fit the player's preference."

HELP ON THE GREENS (AND FAIRWAYS)

That leads to the next aspect, which is how players and their caddies actually use the books. There is great variation here. The presumption, born out by what we see on TV, is that players and/or their caddies use them strictly on the greens. But Dustin Johnson points out that he uses them primarily from the fairway. "When you see us checking our yardage book, we're usually looking at the green [map] just as hard," he says. "I want to know where the straight putts are. And I really want to know how the ball is going to kick after it lands."

Jordan Spieth is largely in the fairway-use camp, too. "He's looking not only at the slope where the ball will land and bounce, but sometimes even the grain so he knows how the ball will run out," says his teacher, Cameron McCormick, as Spieth hit balls on the range at TPC Boston. But Spieth and his caddie, Michael Greller, clearly use them on the greens. There was an instance earlier this year where Spieth, who frequently thinks out loud, was overheard saying as he approached a putt, "Trust the book . . . trust the book!" Zach Johnson also is a green-map reader from the fairway. "Putting is one of my strengths, and I want to leave myself as straight a putt as I can," he says.

Once on the green, players use the books selectively. Most don't consult it on every putt. "They help me mainly on putts that look fairly straight," says Anirban Lahiri, who in September appeared in his second Presidents Cup. "The map often will tell me if I should favor one edge or the other."

Players also consult the maps in different sequences, most doing conventional, eyeball reads first, then going to the book last.

"I still think green-reading is an art," says Jason Dufner. "There's break, speed and aim. I check the book to confirm what I see already, or to help if, say, I think a putt might be a little downhill." Stewart Cink and his caddie, Taylor Ford, prefer this sequence, too. "Ninety percent of the time I just want the book to confirm what I see already," Cink says. "The green maps have limitations. They don't show footprints. They don't tell you if it's early or late in the day. You're putting over a living, breathing surface with all kinds of variables. The books are merely a fine-tuning of information."

StrackaLine

Dufner says the books sometimes convey incorrect information. Long says this can happen when the hole location isn't precise. "A lot can happen if the hole is charted even a couple of feet differently than what's conveyed on the map," he says. Duplantis says improved hole locations provided by the PGA Tour will remedy this. But Long says players sometimes don't plot the location of the ball on the green correctly in relation to the hole, what he calls "operator error."

Players and caddies don't always consult the books together.

Patrick Reed frequently goes to the book, but his caddie, Kessler Karain, chooses to ignore it. "I trust my eyes and instincts," says Karain, the brother of Reed's wife, Justine. "To me, the guides take away from that. When Patrick sees something in the book I don't see, we'll consult. But I'm confident in my senses."

HOW YOUR COURSE CAN BE MAPPED

The use of green maps on the PGA Tour leaves the impression they are available only to the pros. In fact, green maps of many courses, including tour courses like Torrey Pines and notable ones such as Cherry Hills and Bethpage, are available for purchase and download at sites like strackaline.com. A few others—PGA National, East Lake and Riviera are good examples—have sold green-map books over the counter.

There are holdouts. No modern, laser-scanned green map of Augusta National is known to exist. It doesn't mean that their greens haven't been laser-scanned and mapped extensively; when the 11th green was washed away by a flood in 1990, the club used measures taken by a theodolite laser to restore them. "A course like Augusta probably has been measured down to the last pine needle," Mayerle says. You also won't find green maps for exclusive, old-world citadels such as Merion, which hasn't been mapped since the 2013 U.S. Open, or San Francisco Golf Club, which doesn't even sell yardage books.

Any course can have its greens mapped. If a course agrees to purchase 100 StrackaLine books for $15, the company will come in and do a complete mapping. It amounts to a $1,500 charge, which the course can recoup by selling books to its members and visitors. Jim Stracka touts other upsides: "It's very helpful for superintendents for pin-setting, being able to cut the holes where there can be less traffic," he says. "It provides a record in case a green needs to be modified or rebuilt."

For his end, Stracka gets to sell the books through his website. "We're adding roughly 10 new courses a week," he says. "We have two full-time engineers who do nothing but map courses."

Commercially, the most innovative offering is presented through GolfLogix, for years a well-known player in the mobile GPS yardage-guide market. Through its app, GolfLogix recently launched access to green maps of close to 1,500 courses, and plans on bringing the number to 10,000 by 2018. Users can view green contours on the green and from a fairway perspective. Access to the maps will cost $49.99, though PGA club pros will get them for free on request. "They're fun to use and are going to save you strokes," says Pete Charleston, president of GolfLogix. "But one aspect we're excited about is how they'll speed up play."

DO THE MAPS MAKE PLAY SLOWER OR FASTER?

Ah, the pace-of-play issue. We referenced earlier how Dustin Johnson spent an additional 20 seconds consulting his green-map book on the 18th green at the Northern Trust. That decisive putt notwithstanding, tour players have not routinely surpassed the 40 seconds allowed on a putt per tour guidelines. "As I've gotten used to the books and what to look for, I'm referencing them much more quickly," Cink says. "I rarely look at a map for more than a few seconds, but it's a legitimate concern. Those small time blocks can add up." He adds, with a laugh, "If you see us going to the book on our third putt, it's time to call us out."

Long and Charleston say that everyday amateurs having green information immediately makes the maps a timesaver. "You're going to see less walking up to the hole and back on 60-footers, less plumb-bobbing and pacing around in general," Charleston says. Adds Long: "There are presentations coming in map designs in the very near future that unequivocally will speed up play."

The maps have a few detractors. Jack Nicklaus and Johnny Miller expressed broad displeasure with them during the Honda Classic, pointing to time spent and the impression that players are becoming reliant on them. It's worth noting that Nicklaus held a dim view of yardage books until he actually used one (see accompanying story), and Miller in his prime was known for having his caddie, Andy Martinez, give him yardages down to the half yard. The fact that green books have not gained traction on the PGA Tour Champions might indicate a generational shift. "There's no market there," Long says.

Among players on the PGA Tour, Adam Scott, Ian Poulter, Lucas Glover and Luke Donald have gone on record as disliking them. Scott and Poulter have said they should be banned. The art of putting has been lost, Poulter tweeted in March. If you can't read a green, that's your fault. He also said they slow down play. But Duplantis says that each of those players—or at least their caddies—use or have used them. And it can be noted that Poulter, after winning the WGC-Match Play in 2010, later tweeted about how "useful" the green books had been.

USGA, R&A "CONCERNED"

The largest issue, however, is the feeling that with their extraordinarily precise information, the books might be chipping away at the skill and the fundamental challenges of the game. In May, the USGA and R&A issued a statement that said, in part, "We are concerned about the rapid development of increasingly detailed materials that players are using to help with reading greens during a round."

Reading the greens with our senses is "an essential part of the skill of putting." The USGA is choosing not to comment about what it has discovered or if other implications of the maps—say, their effect on pace of play—are being considered. "To be honest, the Rules of Golf department feels uncomfortable discussing it, as it could taint the process," says Janeen Driscoll, the USGA's public-relations director.

The prevailing feeling on tour is that the status quo with green books will be deemed acceptable. "It's hard to put the toothpaste back in the tube," Cink says. "When it comes down to it, green maps really are an extension of yardage books. I don't see a rollback coming." The tour players who expressed disfavor with the concept early in 2017 have been largely silent of late.

With input from Long and other green-mapping wizards, there might be important clues as to the possibilities. "At the pace technology is moving, I believe in five years it will be possible to aim your phone at the surface of the green and have it point specifically where to aim your putt," Long says. And technology experts say the next iterations of apps will be able to give advice on how hard to hit it.

Adds Mayerle, who provided green-contour information for the old Links LS computer golf games: "It's inevitable that the information in green books will be used in virtual reality. You and your buddies putting against Jordan Spieth—live—from a 'green' where a week earlier he holed a monster putt to win a major. It could make green books as we know them now almost seem Stone Age by comparison."

Depending on your point of view, that's either the coolest thing possible, or another scary leap into the future.

Deane Beman

Yes, Pros Used To Play Without Knowing The Yardages

Before there were green maps, there were yardage books. And their history runs deeper, and traces a more circuitous path, than any current player on the PGA Tour probably would imagine—or remember. In the late 1940s, a talented Southern California amateur named Gene Andrews began pacing off yardages from course landmarks to the center of the greens. A Walker Cup player and 1954 U.S. Public Links champion, Andrews swore by his method and its ability to aid in club selection, and he tried to spread the gospel to fellow amateurs. Few listened, let alone obeyed.

Unknown to Andrews, playing by yardage was being developed independently in Bethesda, Md., by a 17-year-old named Deane Beman. Yes, that Deane Beman. The future commissioner of the PGA Tour, completely unaware of what Andrews was doing, actually jotted down yardages on his scorecard at the 1955 U.S. Open at Olympic. It's what's known as "multiple discovery."

"I used to go to a football field and practice taking three-foot steps so I could put them in as yardages next to holes on my scorecard," says Beman, retired and living in Ponte Vedra Beach.

"I got to where I was rarely off on the 100-yard distance by more than a couple of yards. I'd walk courses in advance, measuring from trees, sprinkler-head couplers and corners of bunkers."

At the Walker Cup in 1959, Beman showed his method to one of his teammates, a beefy teenager named Jack Nicklaus. "Jack used to scoff at my writing down yardages," Beman says. "He wasn't interested at all. Then, at the 1961 U.S. Amateur at Pebble Beach, he started copying my numbers onto his scorecard. He never looked back. Jack was a heck of a lot more influential than I was—after he turned pro, a lot of players started sending out their caddies to get yardages."

The phenomenon wasn't particularly organized or systematic. But it turned a slight corner when Ernest (Creamy) Carolan, who caddied for Arnold Palmer, began laminating the pages of his books, spreading their popularity and raising the standard for accuracy.

"By 1972, it really started to take off," says Steve Hulka, who caddied for David Graham during that period. "I recall groups of caddies, four or five of us at once, getting yardages together and sharing the information. Everybody used a yardage book. Eyeballing was dead."

The commercialization began, according to Hulka, in 1976, when caddie George Lucas began selling his hand-drawn, meticulously crafted books for $5. It's Lucas who drew in colorful rejoinders in his books, such as "J.I.C.Y.R.F.U" (Just In Case You Really F--- Up) to indicate awkward places.

The turning point came in 1996, when caddie Cayce Kerr began measuring with a Swarovski laser he acquired in Europe, selling models to players and caddies—at an escalated price.

"That changed everything," Hulka says. "The laser doesn't lie, so the old-school methods of walking with a calibrated wheel or using fishing line were gone forever. What's funny is, George Lucas found a cheaper Bushnell model in a Cabela's catalog, which sort of destroyed Cayce's little side business."

Yardage books as we know them today appeared in 2003, when Mark Long began distributing them through his company, Tour Sherpa. There are a few holdouts on the green maps, but to every player, the modern yardage book rates second only to a player's clubs in importance. – Guy Yocom