Do It Yourself: How To Build Your Own Clubs

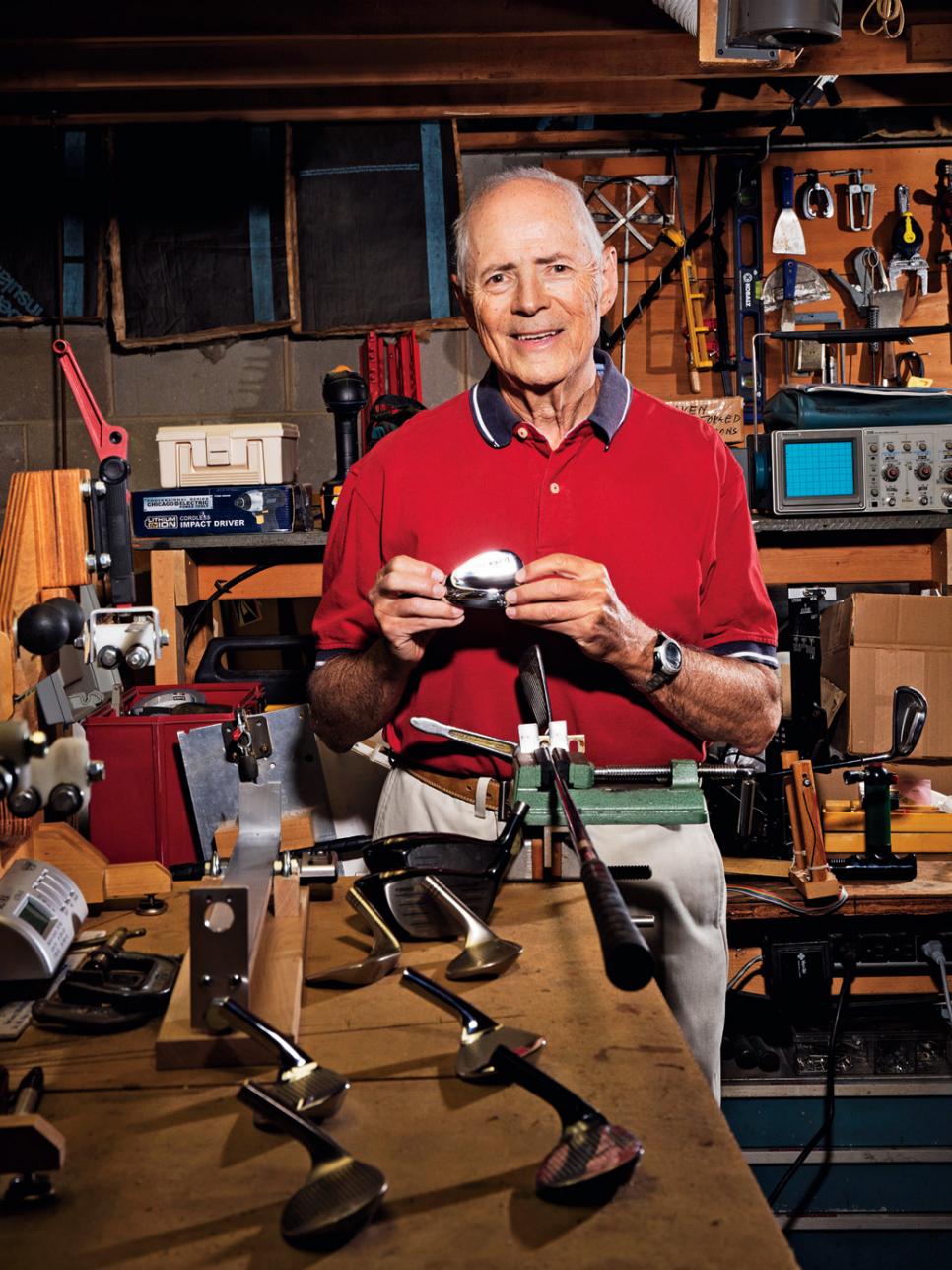

Nathaniel Welch

Given that the latest drivers are easier to find than ever, and custom-fit irons are accessible with a couple of mouse clicks, the idea of making your own clubs seems about as worthwhile and archaic as building model trains or canning your own vegetables.

But component clubmaking beats to a different logic. The passion isn't about arithmetic or economics or even lucid calculations of cost-benefit analyses of time commitments. No, it's a hobby fueled by a ravenous quest for self-knowledge. The whys don't really enter into it.

For Glenn Weatherspoon of Arvada, Colo., who has been making his clubs for four decades, no other way makes sense. His voice echoes with the experience of a basement workshop full of chop saws, belt sanders and enough two-step epoxy to shingle a roof. It all began for the 6-foot-10 Weatherspoon when a local golf-shop salesman swore everybody's specs were pretty much the same. "The guy was 5-5," Weatherspoon says. "How can he not see that my knuckles are a foot farther off the ground than his? When he said, 'Building your own clubs? That's impossible,' well, that really got me going."

Basic clubmaking is fairly straightforward. Guides and videos abound on sites like Golfworks.com and Hireko.com on how to cut a shaft to the proper length, how to use the right amount of solvent to slide a grip over an extra wrap of double-sided tape, how to line up a ferrule flush against a clubhead. But attention to detail is as mandatory as breathing. Any mistake, and you'll likely be starting over. A basic home workshop might require only tools picked up at a local hardware store (bench vise, sandpaper, utility knife, hacksaw); others might feature swingweight scales, club moment-of-inertia monitors and digital-frequency analyzers.

More of the latter is what you'll find at Dave Tutelman's workshop in Wayside, N.J. The Bell Labs engineer of 40 years has even built gauges and scales. His background has fueled his interest in understanding not merely how to build the best clubs for himself, but turned him into a self-made golf-technology researcher. His website (tutelman.com) has deeply considered answers to questions ranging from average golfer distance potential to single-length irons. His start in the 1980s, however, was based in practicality. "My kids were just starting their teens then, so I certainly got into it because it was a bargain," he says. "But I continued it because I was an engineer, and it was really fun to figure it out, to build it and see whether it works."

Tutelman has never stopped seeing whether it works. He's got an e-book on his website that covers every aspect of clubfitting and club design. He presents a compelling technical analysis that drivers with extremely low centers of gravity might produce less spin on tee shots but might have a point of diminishing or even counterproductive returns.

‘My kids were just starting their teens then, so I certainly got into [clubmaking] because it was a bargain.’

Though it's hard to paint the lot with the same brush, these geeks seem to adopt that same intense inquisitiveness, that desire to explore through experimentation, all while crafting an implement that is as much tool as it is treasure. Ron Zaskowski, a former Evans Scholar and retired IT specialist in Michigan, has been helping make clubs since his days as a caddie and later as "free weekend help" at his father's golf shop. He continues to straighten out struggling players on the local high school team, spotting a dysfunctional club as easily as a veteran birdist recognizes a black-crowned night heron.

"I've always had the feeling that I was in more control of the finished club if I was doing it myself," he says, acknowledging that today's prevalence of custom clubfitting by all the major brands and retail outlets has reduced the appeal of do-it-yourself equipment. "Sure, the stuff today is better than it was 15-20 years ago. But I just enjoy the process, discovering something I didn't know. A lot of folks just aren't like that anymore."

Though the number of clubmaking hobbyists has dwindled since the 1990s, there is evidence of a resurgence. "We've really started to see our schools fill up, and our tool sales like grip-changing stations, shaft pullers, swingweight scales, we can't sell that stuff fast enough," says Britt Lindsey, vice president of technical services and R&D for The Golfworks, from whom you can buy a build-your-own-driver pack for less than $200.

Talk to this crowd for even a few minutes, and the modesty falls away. There's pride in the work, confidence in knowing what can go right or wrong with every pass of a sole under a grinding wheel. Golf-club hobbyists say it makes them better at golf, whatever "better" means. For Weatherspoon, a big-hitting competitive amateur in his day, it's more than the number.

"You don't have to be a metallurgist, but you do have to spend time looking into the differences between steels and their characteristics," he says, like how much more difficult it is to bend his severely upright lie angles with a cast 17-4 stainless-steel head compared to 431 stainless. "And that spoke to me. At the same time, I don't have to pay attention to all that background noise about the next latest and greatest. It gives me a bit more serenity in my game."

'My kids were just starting their teens, so I certainly got into it because it was a bargain.'

It's a hobby fueled by a ravenous quest for self-knowledge. The whys don't really enter into it.

MORE DO IT YOURSELF GOLF

▶ Do It Yourself: How To Build Your Own Simulator

Playing every day is cheaper and easier than you think.

By Matthew Rudy

▶ Do It Yourself: How To Build Your Own Putting Green

For homeowners desiring to pack more golf into their lives—not add a chore—a synthetic-turf green is the way to go.

By Max Adler

▶ Do It Yourself: Swings

Even instructors agree, the best players are often self-taught.

By Joel Beall

▶ Do It Yourself: How To Make A Training Aid, Sunday Bag, And Headcover

By Keely Levins