Next After The Knee

The State of Tiger: This is Jaime Diaz's seventh annual assessment of Tiger Woods' year, and career, in golf. For previous installments, see the related links box below.

Tiger Woods and Anthony Kim are squared off, just as everyone would like to see them in 2009.

The setting, of course, isn't the final nine of a major but a clinic on a shimmering October day off the Pacific. Kim is hitting the shots while Woods—his celebrated left knee still on the mend—faces him from a few feet away and does the commentary. Tiger is holding a club, but his last full swing remains a 9-iron approach to the seventh green at Torrey Pines on the 91st and final hole of the 2008 U.S. Open, back on June 16.

Kim, 23, casual and confident but also concentrating, is striping it. He's got speed, his swing plane is perfect, and the sound of club against ball and ground is the aural definition of flush. It's the action that in July produced a closing 65 at storied Congressional to win the PGA Tour event Woods hosts and made Kim the first American under 25 to win two events in one year since ... Woods. Kim is the guy who Woods' ber-mentor, Mark O'Meara, contends has better technique than Woods had at the same age. And succession fetishists can thrill to the fact that there's a decade difference between the two, as with Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, and Nicklaus and Tom Watson.

"Pretty pure there," says Woods, watching another 3-iron. "Seriously, you missed a shot yet?"

"Just lucky," answers Kim, the compliment turning him shy.

Enjoying his role as relative elder statesman, Woods jokingly wonders, "Maybe I should stay retired."

Woods clearly likes Kim, a former wild child who has straightened up. Tiger has encouraged him the way he once did with Sergio Garcia, the way he never has with Phil Mickelson or Vijay Singh. The two have an easy banter. They are both from SoCal, both with Asian heritage, both with enough authentic athletic chops to feel occasionally boxed in by golf. When Kim arrives at the event wearing a white belt with "USA" in red, white and blue rhinestones, Woods cries, "Give it up!" Later, when Kim tries to convey to the assembled how lucky he feels for the chance to learn face to face from "a guy who has won 10 majors," the holder of 14 tilts his head in disbelief and intones, "TEN majors?" After Kim responds with a shrug, Woods plays the offended purist. "Come on!" he yells. A couple of beats later, still comically appalled, he says it again, only louder: "C'mon!"

Kim laughs with everyone else, content for now with the notion that anything that doesn't help him get the ball in the hole quicker can only clutter his mind. Though as an adolescent he drew inspiration from watching a Tiger video, his feel-oriented, right-brain approach contrasts sharply with the analytical Woods. "I just have to let my body take over and not let my mind ruin what my body is capable of doing," Kim explains. Woods is all about understanding cause and effect.

"When I was a kid, I was the kind who really bugged my parents with 'Why?' " Tiger says. "And they always had to have a good reason, because I would analyze it, and if it wasn't a good reason, I'd ask, 'Why?' again. If I don't know why, then how in the hell am I going to fix it?"

The character trait revealed in this last sentence is the raison d'être of Woods' Hoganesque approach. He has always believed he has an edge against players who would rather not know why, and when Kim is imprecise in explaining his ball positions for various shots, or confesses that he plays a fade because a draw makes him nervous, or sneaks a look at the sole of his driver before saying "8.5" to a question about its loft, it isn't a stretch to surmise that the "Anthony Kim: Possible Weaknesses" file in Woods' head is getting thicker.

Still, this is Woods unplugged. Below the hem of his shorts, a vertical surgical scar along the left knee that was operated on June 24 is revealed, but any trace of a limp—or a game face—is gone. His past two weeks have been devoted to promotional work. Along with corporate schmoozing and interviews, it has meant watching a lot of bad golf, especially from the man who won Woods as a caddie for nine holes at Torrey Pines but was so nervous he barely spoke to his cart mate for the first four holes. Yet at the clinic, Woods betrays no impatience and specializes in icebreakers. Sidling up to 15-year-old Seth Jones, whose father, Jason, is playing in the pro-am, Woods notices the teenager's braces and, remembering his own orthodontic ordeal, grabs a packet from the snack table and deadpans, "Beef jerky?"

"He's calm and balanced," says Woods' athletic trainer and physical therapist, Keith Kleven, who has known him since the year before Tiger entered Stanford. "The family, the way he talks about the baby and the one on the way [due in February]. He's centered in everything right now, the best I've ever seen him."

Woods concurs. "I've been working so hard on the rehab part of it, it hasn't been hard to forget the golf part," he says. "In a couple of more months, when I'm able to rotate and move on this thing a little more, I'm sure I'll have the itch to come back. But this down time has reconfirmed that I won't have a problem when I have to walk away from the game. It's not going to be that hard."

Of course, Woods has been fortunate to fill any potential void by being an active participant in the most formative period in the life of his daughter, Sam.

"We're all proud of our kids, and I'm no different," he says. "Watching her learn how to talk—yelling at the dogs like I do. We play catch. She's 16 months . . . she'll catch it and throw it right back to me. I wouldn't have seen all this if I had been playing a lot. It's something I talked about with Jay Haas [a father of five]. I told him, 'It's harder to leave home.' He said, 'Wait until they tell you, "Don't leave, Daddy." That kills you.' That's something I'm not looking forward to at all."

At the same time, Woods sees the whole domestic package as a help, not a hindrance, to his golf.

"From what I heard, when I first got engaged I was going to become a worse golfer, and when I married Elin I was going to become a worse golfer. Then after we'd had a kid, I was going to get worse again. But I've become a better golfer with each event. They've all made me a happier person with a more rounded life. All these people who basically said I would lose it because of all these different things, they have no idea."

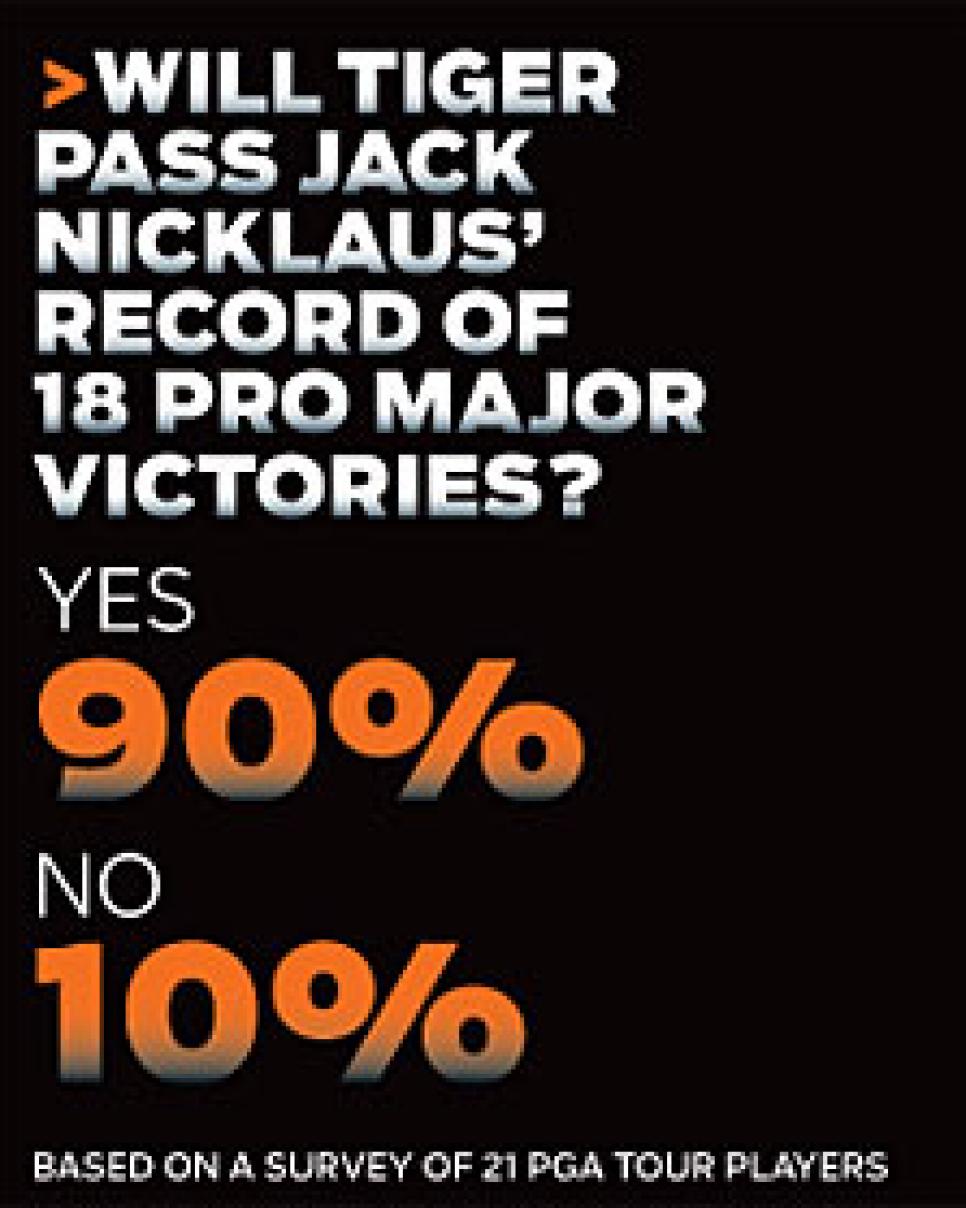

So, is this injury break another karmic moment in the charmed life of Tiger Woods? A perfectly timed halftime, a long moment to reassess and plan for a career second half that should include passing Nicklaus' 18 majors? Woods sees it as much more pedestrian.

"I just see it as rehab, something a professional athlete has sometimes got to do," he says. "My life changed dramatically when my dad died [in 2006]. To make that adjustment in life, that was hard. Then, after losing my dad, the next year to have Sam—those were polar-opposite experiences. To be as low as I could possibly be, to be as high as I could possibly be, all in one year. If you want to create halves, that was that transition. To have knee surgery, that's easy."

It's not to say that the break won't be beneficial.

"It can only do him good," says instructor Hank Haney. "It takes a tremendous amount of mental energy to do what Tiger does. More than most people can imagine. It's good for him to rest, to visualize, to prepare. On the other hand, he's so good at mind control that he keeps himself from saying he misses it, because that doesn't do him any good."

Woods also has a chance to fuel up for paybacks to skeptics, doomsayers and those who long to see him fail.

"When you have desire like Tiger has, when people write you off and say you're finished, you like that," says Lee Trevino. "I heard that stuff my whole life, and I loved it. Whenever I was in a hospital bed or laid up, my mind would be running, thinking about all the things I was going to do. Tiger's going to come back with a vengeance."

Woods doesn't bite on the payback angle, but when asked if he ever has to fight fears that his best golf has been played, or that he'll never be the same, he says, "I never look at it that way. Anyway, I don't want to be the same—I want to be better."

He has more than ever to build on. It's easy to forget that before his operation, Woods was on his longest ever sustained run of excellence. From last August through the U.S. Open, he won 10 of the 13 events he played, all with an anterior cruciate ligament that ruptured while he was jogging at home the week after the 2007 British Open.

Counting Dubai, Woods won four consecutive times to open 2008. "A lot of it was due to Tiger changing his swing after he tore his ACL, to take the pressure off the knee," says his caddie, Steve Williams. "He really made a conscious effort to shorten his swing a little bit and tried to keep everything a little quieter through the ball. He ended up hitting the ball more consistently than he ever has. Then in the offseason he worked on his short game, kept hitting the ball just as well, and came back even better. I thought the venues for the major championships were particularly to his liking, and I really believed 2008 was going to be a huge year."

For Woods, his standard of play was the fruition of all the work he had done with Haney since 2004. "All the things that Hank and I had been working on over the years were starting to take shape," he says. "The only thing missing was getting the proper leg action, and that was because of my knee. But I finally felt like I started to understand my golf swing. I could fix it when I was out there playing, could make the adjustments mid-round from shot to shot. I was more consistent day in and day out because of it."

Even in a truncated season, and with Torrey as the exclamation point, the legend grew.

"It all just reinforced the idea that Tiger is something extremely special," says John Cook, a close friend. "People stopped talking about a rival because there isn't one. Maybe the key is his humility. He's never above learning, and he always wants to learn more and do better. At the same time, there's definitely something different about him. Without ever saying so, he knows what his place is. The best golfer ever, for sure. One of the greatest athletes in any game, ever. One of the great humans at anything, ever. He knows his place."

And Woods is fully honoring his gift. He was once seemingly fatalistic about the knee, which he now admits he first injured as a boy daredevil engaged in X-Games-style activities that had nothing to do with golf. In recent years he was lifting heavy, running hard and grunting through military-influenced workouts with Navy Seals he had befriended. Woods still seemed defiant about limitations at his post-victory press conference at the U.S. Open when he said. "I'm not really good at listening to doctors." But now he is.

"What he's told to do, he does it, and he does it at the highest level," says Kleven. "It wasn't always the case, but he's grown up a lot. He's learned that everything the doctors, the trainers and the therapist say is for a reason. On his own, he studies and has a vast knowledge about the injury, the surgery, the rehab. He knows everything about what's been done and what he needs to do."

Woods could be excused for being cavalier when his winning percentage increased after the tear of the ACL. But the resulting instability caused painful cartilage damage, which he chose to clean out after Augusta. His plan was to get through the PGA Championship before having surgery to repair the ACL, but his quad and hamstring atrophied to the point where they could no longer hold off bone-to-bone contact in his knee joint. Trying to cram in preparation for the Memorial Tournament—scheduled as his sole tuneup for the U.S. Open—proved too much.

"I was just practicing at Isleworth, hitting a normal 5-iron," he says. "I felt something kind of give, and it hurt, but I thought, It's just pain. I kept hitting balls, but it kept getting worse and worse and worse. This was a different type of pain. Two days later we had it X-rayed, and they found the cracks."

Woods' stress fractures—what Kleven describes as "little lightning bolts down through the connecting tissue and the cartilage"—were in the left tibia. Kleven says that Woods had so much pathology in his knee that the surfaces of the femur, tibia and fibia were rubbing together. "That's really excruciating pain," he says.

So intense that the week before the U.S. Open, it was difficult for Woods to hit more than two practice shots without having to sit down. Still, he was steadfast about playing at Torrey Pines, the site of his Junior World and Buick Invitational victories.

"I'd never seen him talk about a tournament so much before it started than he did about Torrey Pines," says Williams.

Woods also talked when he got there, buoying himself by repeating two self-fashioned declarations.

The first was to Kleven, who was charged with managing Woods' increasing pain. "It was probably the toughest week I've ever had in any sport, and the most relieved I've ever felt about anything when it was finally over," says Kleven, who was in heavyweight champion Larry Holmes' camp for several title defenses. "Between stimulation and ice and some different systems that I use, you could block the pain, but you can't block it for the whole day. It would come back during the round, and all the bending over and grimacing he was doing, that was the pain response to bone to bone and him doing whatever he had to do to get through it. Endorphins kicking in from the emotional part of competition probably kept him from feeling as much pain as a person would normally feel, but by the time he got back to the room he was wrung out and just wanted to lie down. We'd do several sessions from dinnertime to 11 or 12 at night, and then again in the morning before he played. We really didn't know how much damage he was doing inside. I would ask him, 'Are you sure, Tiger? Because we can't lose your knee,' or I'd say, 'I don't know if we can go.' And he'd react like a boxer in the corner: 'No, we can go, Keith, we can go. We can do this.' But most of the time he'd just come in and say, 'I hurt it; you fix it.' He said that over and over."

Woods' other mantra was saved for the golf course. "Tiger kept repeating this one sentence," says Williams. "He'd say, 'Stevie, I'm going to win this tournament, I don't give a s--- what you say.' He'd say it after a good shot, or a bad hole, or just to keep things light. It was a way to reassert his belief and just keep going."

Woods needed an extra helping of will to overcome four double bogeys (three of them on the first hole). "Really, there is no way I should have won," he says, shaking his head. "Do I think about that a lot? Yeah. . . . Yes."

Woods had to rely on his team like never before at Torrey, and the most timely help of all came from Williams. The man who will be remembered as the finest caddie of all time made what he considers his greatest call on the 72nd. Needing a birdie 4 to tie, Woods faced a 101-yard third shot from deep rough to a front-right flagstick on a very firm green also protected by water. Williams paid attention to details but trusted an instinct honed during stints with Hall of Famers Peter Thomson, Greg Norman and Raymond Floyd.

"There was a lot of talk between us, and I managed to sway Tiger to the [60-degree] lob wedge, which he normally doesn't hit more than 85 yards," Williams says. "The shot that he had in mind, using a 56 to bounce the ball up without much spin, I just couldn't see. There was a steep bank in front of the green that kicked everything hard left. With that shot, if you dropped 20 balls you could get the ball close maybe once.

"I knew he was pumped up, and I knew we were coming out of that tight Kikuyu grass that still had some dew on it even though it was late in the afternoon, because that side of the 18th stays in the shadow of the hotel. I knew that the moisture would help him hit it farther. I just had a feeling. I could envision him hitting that club as hard as he can and being able to get that distance out of it, with enough spin to stop it. Of course, if it didn't come off it was going to be a very long nine months. But it turned out perfect."

Well, 12 feet away. His recounting of that bumpy putt offers a window into how Woods' mind works under pressure:

"I was reading the putt, a ball and a half outside right, thinking You can't control the bounces; all you can control is making a pure stroke. Go ahead and release the blade, and just make a pure stroke. If it bounces off line, so be it, you lose the U.S. Open. If it goes in, that's even better. I hit the putt, it felt pure, and I hit it just right where I wanted to. It's rolling down there, I'm just, *Break . . . please break . . . break . . . not breaking . . . *and then it started to barely move left, and at the very end it just dove. And as it dove, it caught the right edge of the lip and went in, and you saw me with some stupid reaction."

Woods had to make another birdie putt on the 18th the next day—a slick 4½-footer—to send the playoff against Rocco Mediate to the 91st and final hole, where Tiger won with a par. The entirety of the accomplishment makes Woods reflective of his early years.

"I grew up with a whole bunch of different military people—highly motivated people, and great people to be around," he says. "I grew up with a Marine, with a Navy captain, a Navy admiral. A couple of the guys were in the Army infantry, and my dad was Special Forces. So, this is what I saw. I saw the discipline side of it. I saw how to handle things. Whatever it is, you get the job done. Like my dad would explain to me, 'Just because someone gets shot doesn't mean he's not effective. He can still operate. And just because you hit a bad shot doesn't mean your whole round is over. You can still turn it around. You can still operate. You can still get it done.' "

As Woods does whenever he tries to make sense of his knack for great shots when he needs them most, his thoughts go back to seminal playing lessons with Earl Woods.

"How do you explain to a 4-year-old not to have negative thoughts?" Woods asks. "My dad would say, 'Where's the trouble?' I'd see water left and bunker right. 'OK, where do you want the ball to go?' 'I want it to go there, Daddy.' 'OK. What kind of shot do you want to hit?' 'I'm hitting a low draw.' 'OK, do it.' And I'd put the ball right there. And he'd say, 'OK, good.' And that's the way I grew up playing. So it's hard for me to explain negative processing. Even to this day, when I'm out there struggling and I don't have my best stuff at all, I'll go back to, 'You know what, Daddy, I'm going to put the ball right there. Right there. I'm going to put that little 2-iron right there, Daddy. No problem. I got it.' Boom, I put it right there . . . "

Momentarily lost in the moment, Woods concludes the soliloquy with "Thanks, Pops."

Woods believes he'll be able to hit it where he's looking more often with a surgically repaired knee. Because of the weakened condition of the joint, Woods couldn't keep his left leg from hyperextending at impact. With a sound knee and sufficiently strengthened surrounding muscles, he is convinced he'll be able to avoid the straightening snap that caused so much wear and tear.

"I've always thought Tiger—good knee or bad knee—swings too hard," says Trevino. "Now I believe he'll learn to brace that left knee at impact instead of straightening it. In other words, swing more like we did, with a bent left knee and a little slide. It means he won't be able to swing the club quite as fast. And that will give him better accuracy. And then it's over, because when he drives the ball in the fairway, he's the best at every single part of the game from 180 yards and in. He might win every tournament he plays. He's the most intelligent player I've ever seen about the golf swing. He learns everything, overcomes anything."

Haney says Trevino's analysis is spot on, except the part about not being able to swing the club as fast. "When Tiger was hanging back on his right side because of his leg, it appeared that he was swinging too hard because he would kind of wheel his body around at the last second," Haney says. "Actually, that was slowing the club down. With a more correct swing, where he gets fully onto his left side, his downswing will appear smoother, but the club will be going faster. And the ball will be going straighter."

According to Woods, "I couldn't be as good as I wanted to with the longer clubs, couldn't really do what Hank wanted me to do, especially the driver, because the more speed and leverage, the more it would buckle. I knew it, and Hank knew it." Here, Woods smiles. "Not that I was going to say anything about it. Why? Unless my timing was really good, I would have to find a way to play around my driver. Mainly, I had to putt well. But I'm going to finally be able to get into my left side, and that's exciting."

Still, as Woods awaits a return to the tour before the Masters, his advantage over the competition might have lessened in his absence. Padraig Harrington won the remaining two majors, in the process extolling the pursuit of improvement. After Kim doubled up, Camilo Villegas won the last two events of the FedEx Cup, demonstrating a suddenly integrated melding of power, touch and resolve. It was clearly Tiger-like.

And not by accident. "If you listen to his words, Tiger makes his methods accessible," says Dr. Gio Valiante, who has been Villegas' mental coach for several years. "It happened with Hogan and Nicklaus: The dominant golfer of the generation revealing how he plays the game, the subsequent generation able to study that and then saying, 'It's possible. If he can do it, I can do it.'

"The first 20-somethings who followed Tiger probably were too close in time to fully absorb his lessons," Valiante says. "But now players like Camilo and Kim have. They know intuitively, for example, that Tiger made it OK to be selfish. Nicklaus wrote 'golf's gentlemanly code requires that you hide your confidence.' Tiger changed that when he came out fist-pumping. At the time, guys were complaining, 'Don't bring that to golf; it's disrespectful and arrogant.' But Tiger proved the fist pump was about something bigger, about accomplishing the most difficult thing in this game, which is to be free. To be fully engaged, without inhibition, without indecision, without fear. To release.

"The blueprint is out there," Valiante says. "The question I've put before Camilo is, 'Why not you?' "

Woods surely plans to provide an answer, but he avoids tipping off any counter moves.

"It's fun to see the next generation of players, but I haven't been out there or watching," he says. "I haven't seen how they've been acting or talking. I don't know how they're acting coming down the stretch of a tournament, because I haven't seen their eyes. I don't know any of this stuff." But then he adds a very knowing getaway line: "Most of their success has come when I wasn't there."

In 2009, he'll be back.