A Thinking Man's Game

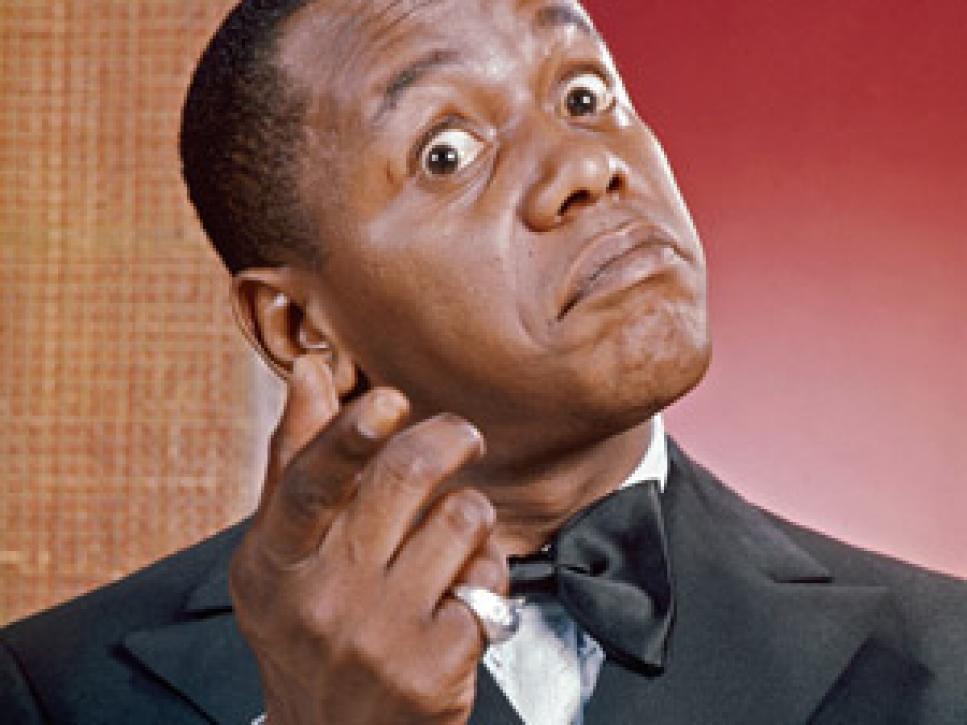

David Wilson had it made. The son of '70s TV star Flip Wilson, he grew up in a beachfront mansion in Malibu. Flip coined some of the era's most popular catchphrases--"Here come the judge" and "When you're hot, you're hot" and "What you see is what you get!" He made the cover of Time magazine as "TV's First Black Superstar."

Flip played celebrity golf with tour pros and presidents but never broke 100. Tall, athletic David was the golfer in the family. "I was decent," he says. "Got my handicap down to 2."

David's silky swing generated just enough power to get him around Riviera Country Club

in the low to mid-70s, but his real strength was course management--staying out of trouble, thinking a shot or two ahead. In the early '90s he moved to Palm Springs, where he could play and practice all day while taking classes at the College of the Desert. "I was dreaming of Q school, but it's a long way from 2 to scratch, and a long way from scratch to the tour. So I studied country-club management." Anything to make a career in the game.

His father was retired by then, living high off the millions from his show and investments. Flip sailed around the world and raced high-altitude balloons with his friend Rocky Aoki, the Benihana founder. (When Flip told a pretty girl he was the world's only black helium-balloon pilot, she said, "What's black helium?") And Flip went crazy for motorcycles, zooming around L.A. on a Harley-Davidson Softail.

David was no biker--it's tough lugging your clubs from PGA West

to Desert Dunes

on a motorcycle. But his dad bought him a Yamaha anyway. "Think you can keep up with your old man?" Flip asked.

On St. Patrick's Day 1993, David crashed on an access road behind the Palm Desert Marriott and was found unconscious. The next thing he knew he was lying on his back, looking up at the stars.

"That was nearly 20 years ago," David says, "and I'm still trying to save a couple strokes."

He's longer off the tee these days. His bunker game is a little better. And there's one other game-changer: Ever since the motorcycle accident, David Wilson has been paralyzed from the shoulders down. Since March 17, 1993, he hasn't walked or even stood on his two feet. Since that day, his golf has been all in his head.

MENTAL GOLF ISN'T EASY

Lying in a steel-framed hospital bed, David, 52, stares at the ceiling of the room where he spends his days and nights. Picturing himself on a golf course, he thinks his way from tee to green. American POWs did the same thing during the Vietnam War, imagining rounds of golf during long stretches in solitary confinement. One report told of a soldier who stayed sane by playing a full 18-hole round. "He would create the trees, the smell of freshly trimmed grass. He felt the grip of the club in his hands as he played his shots...the setup, the downswing and follow-through. Watched the ball arc down the fairway and land at the exact spot he had selected. All in his mind."

David says mental golf isn't as easy as it sounds. Not if you do it right. Sure, you could picture making an ace on every hole, but that's a Jesus-and-St.-Peter joke, not golf. The game has to be realistic, or it would be pointless. "I started out by remembering shots I had hit. Rearranging them. Then I'd picture what might happen with a different club, or if I tweaked my swing plane a little."

The game he developed over the years calls for concentration, visualization and muscle memory. As it evolved he replaced his early-'90s clubs with better equipment. Virtual metal woods made him 10 to 15 yards longer off the tee, and he switched from vintage Wilson Staff golf balls--"I played 'em for the name"--to newer, more workable balls. But the essence of his game never changed. He's a purist that way. "I was never great at drawing the ball," he says. "I hit a high fade. So I might experiment with my grip or stance or plane and try to draw one once in a while, but it's a low-percentage shot for me." When he tries it, he misses his target more often than not. "I'm better off hanging one out to the right and hitting a longer approach."

Maybe with a hybrid. He used to carry a 1-iron and can only imagine the pleasure of whapping a hybrid shot out the rough, but he has imagined it in detail: a steep downswing, the egg-shape clubhead nipping through the grass, the ball taking off on a 7-iron trajectory. "You gotta love technology," David says.

He loves instruction, too, soaking up tips he sees on TV, DVDs and in magazines. His sister Michelle, who rolls her eyes at his talk of forward presses and kick points, reads to him, holding a magazine so that he can see the pictures. David liked a recent Hank Haney tip on weight transfer, "Footwork: Get in the Flow." Haney reminded golfers to keep their weight divided 50-50 at address, 65-35 toward the back foot at the top, 35-65 on the downswing, 10-90 at the finish. David tried it, shifting smoothly on feet he swore he could still feel. He figures a good tip might save him a shot every three or four rounds, but he's cautious about tinkering with his mental swing. Sometimes new moves feel awkward, and he plays worse. Others make so much intuitive sense that he incorporates them not all at once but gradually, his mental swing coming into focus like a super-slow-mo image. "I can improve, but not overnight. I have to keep it real." He never violates the Rules of Golf or physics. With two exceptions: For one, there are no golf carts in his world, because walking is a privilege, a joy. For another, he can make it stop raining.

A FALLING OUT BETWEEN SON AND FATHER

Back in the early '90s, Flip talked Charlie Sifford into taking David on the senior tour with him. Flip wanted David to see what life on tour was like, and to pick up some swing tips. "Charlie Sifford was good to me," David recalls, "but he was playing tournaments. He didn't have a lot of time for playing lessons with Flip Wilson's kid." Sifford was a touring pro, not a teaching pro. After a month of senior-tour stops, David told his father he was going back to Palm Springs. "Charlie doesn't have time to teach me," he said.

Flip was furious. This was his reward for arranging a tour trip with Charlie Sifford? "Oh, I see," Flip said. "You're too good..."

"I just want to work on my game," David said.

"Charlie's got nothing to teach you?"

"No, I just..."

"Screw you!"

With that, Flip cut his son out of his life for more than a year. David phoned his father. He showed up at Flip's Malibu mansion, only to be turned away.

"I was dead to him," David says.

Then came the motorcycle crash.

Flip, crushed, wept over his son's broken body. He paid David's medical bills. David got around in a wheelchair that he operated by blowing into a straw. The chair, and several upgrades he rigged up for it, allowed David to play music, change TV channels, dim the lights in his room and wheel around corners at dangerous speeds. Then, in 1998, Flip was diagnosed with liver cancer. David, living with a friend, hired an ambulance to rush him to his father's hospital room, where they lay side-by-side on hospital beds.

"Wouldn't you know it?" Flip told the National Enquirer. "My boy would find a way to come to my side on the day I need him the most! My eyes filled with tears when I saw my David."

Flip died in 1998, leaving each of his four children $375,000 out of a fortune estimated at $25 million.

"People said we got screwed, but Pops always said we should look out for ourselves," David says. "To me it was a blessing to get anything."

His medical bills mounted, and the wheelchair went into storage. In 2002 he moved to the Philippines, where round-the-clock care costs a fraction of what he spent in California. Today his inheritance is almost gone. He rents a house in Dumaguete, a coastal town on the Philippine island of Negros, where an active volcano leaks steam into the tropical sky. He shares the house with his elderly mother, four full-time caregivers and a pair of watchdogs. Still it gets lonely in Dumaguete, 7,400 miles and nine time zones west of PGA West and 5,000 miles west of Honolulu's Waialae Country Club

, another course he played with his father.

To get to their rental home from Dumaguete airport, you hire a Philippine tricycle, which is basically a motorcycle pulling a rickshaw. Ride past Dumaguete Harbor, where a cargo ship lies half-sunk in the shallows, through crowded, diesel-scented streets lined with Internet cafés, car-repair shacks, fruit stands, chickens and goats. On the outskirts of town, a dappled cow nips grass from a ditch. Across the road stands the Wilson house, defying the island's fierce termites, behind a steel gate and a stucco wall topped with shards of glass. Most of the Philippines' kidnappings and killings of foreigners occur on Mindanao, the next island to the south, but David can't afford to be careless. "It's not like I could run away."

He can't get the Golf Channel, but he watches tournaments on the U.S. networks and the international edition of ESPN, rooting for Tiger Woods, half-Filipino Jason Day and Fred Couples, whom he knew in his Riviera days. The telecasts start between midnight and 3 a.m. local time, filling the wee hours on weekends. But if he wakes on a weeknight there isn't much to do but wait for the sun to come up.

Not long ago he awoke a couple hours before dawn. As a C-4 quadriplegic, David can move his head, neck and shoulders but nothing else. His knees, elbows and other joints, dislocated after 20 years of paralysis, would ache if he could feel them. His shadowy bedroom was still. Nothing moved but the drapes by an open window, stirred by an oscillating fan. A rooster crowed in the field across the road. A motorcycle zipped by, its headlight tracing the ceiling. These are the hours when a man could give in to self-pity. David tries not to. "Yes, I'm handicapped," he says. "My handicap is 2."

He sees himself stepping onto the tee, feeling his Softspikes in soft grass. This could be any hole anywhere, but it helps if he knows its details. At the 12th at Augusta National

he might posit a swirling wind that knocks his tee ball into the front bunker. Digging his feet into the sand, he'd worry about thinning one into the azaleas behind the green, and try to banish the thought while thinking it. "Mental golf is 99 percent mental," he says with a smile. And this shot calls up a good memory."Just before my accident I started really tucking my elbows on sand shots, keeping my right wrist quiet, clubface open through the follow-through. I was getting up and down over and over!" He splashes the ball out and saves par.

Keeping it real, he makes his share of bogeys. "Suppose it's a long par 4 with the pin in the front-left corner. If I'm playing mentally with Phil and Bubba, they can go at that pin, but not me. I never had that shot."

Now and then he'll make a run at his career-best score. When it happens, his pulse quickens. "Even mentally you can get out of your comfort zone. You think, Can I keep it up? And you're not comfortable till you make a couple bogeys." Stuck in his bed, trapped in his body, still trying to improve, he dreams of playing the round of his life.

"Last night, Riviera." He saw himself at the short par-4 10th, fading a 3-wood to a spot 30 yards from the green. "Jack Nicklaus calls that hole one of the great par 4s. It can eat you up or give in. The green slopes hard from right to left. I punch a little 7-iron approach that checks up four feet under the hole. The putt breaks left. I play a half-cup break and bang--got it. I'm two under par for the day."

At the 564-yard 11th, "I fade it too much off the tee. Stick it in that nasty kikuyu grass. You can't get greedy from there. I hit a 9-iron as far as I can, about 70 yards. Smack one close from there and make the putt. Three under." He needs birdie at the famous 18th to shoot 67. "My best round before my accident was 68. I've made runs at that number since then but never beat it. It didn't seem fair unless I really earned it." Could he do that? Shoot the round of his life from a hospital bed?

"Eighteen's an intimidating hole. Long, uphill, usually against the wind. I'm aiming down the left side."

From his voice and faraway gaze, you know he's seeing it.

"There's a steep slope to the left. That's my target, the edge of the slope. I fade my drive to the fairway. It seems to take a long time to walk out to the ball. I figure it's 240 to the flag. It's a great view from here, looking up at the clubhouse. It's not really 240, but the shot plays long into the wind. That row of trees on the right--that's automatic bogey. I take a practice swing, visualizing my high fade. Smack my 3-wood flush, and it fades, but the ball doesn't get to the hole. It lands on the fringe, stops. I've got a 45-foot putt, left to right, uphill. Hit it firm. At first I think it's too firm, but the ball's slowing down as it gets to the hole. It's gonna need one more rotation..."

*Kevin Cook's latest book is The Last Headbangers: NFL Football in theRowdy, Reckless '70s. His biography of Flip Wilson, FLIP, will be published by Viking in 2013. *