Best of Golf Digest

Clifford Roberts: The man who made the Masters

Editor's Note: This story first appeared in the April 1996 issue of Golf Digest. Included is a forward written by Golf Digest's Editor-in-Chief, Jerry Tarde.

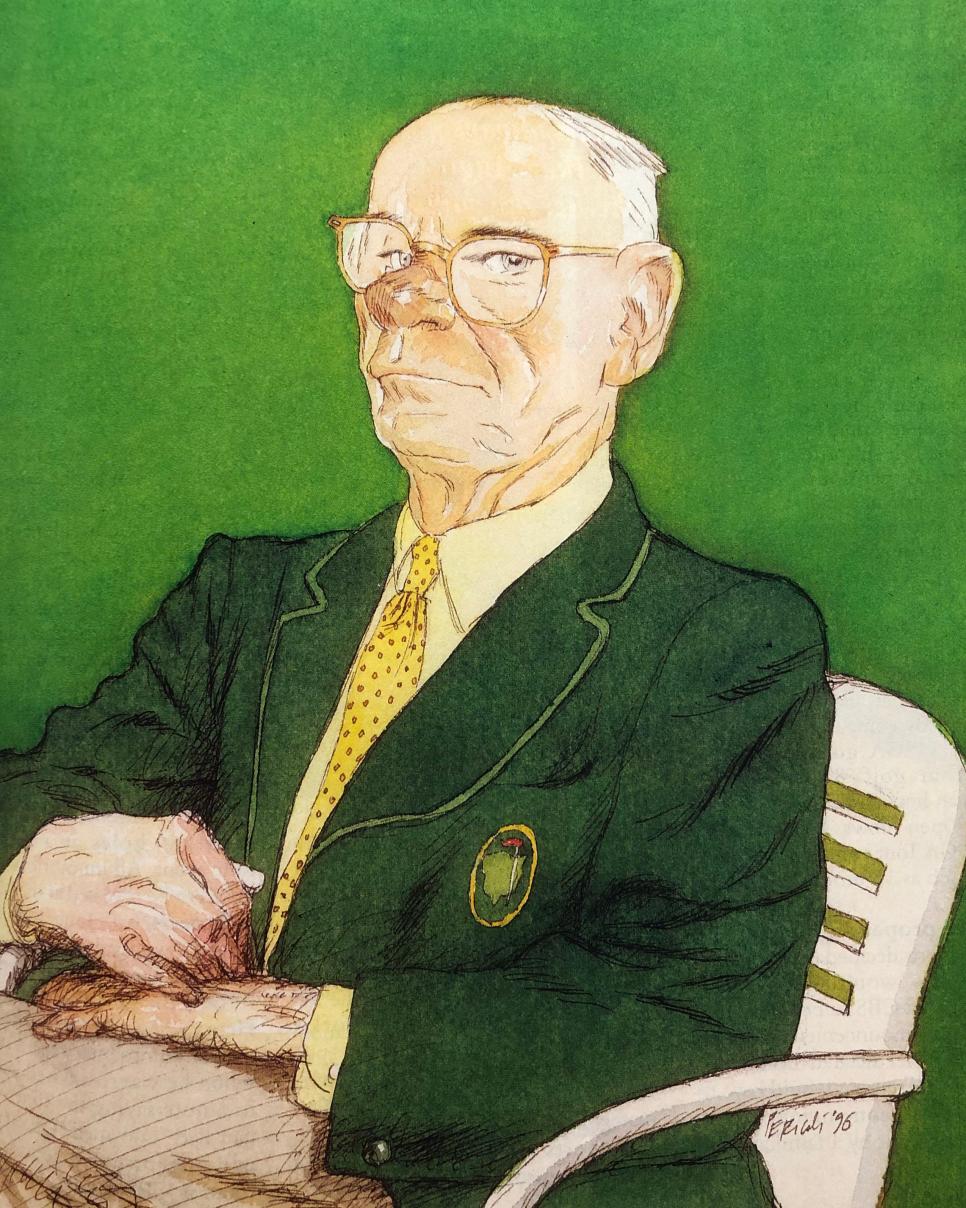

Editors search to match writer with subject, and this piece proved to be one of those happy marriages. Today his name is hardly recognized by golfers, but Cliff Roberts, co-founder of the Masters and Augusta National Golf Club, was the dictatorial visionary who set tournament and club standards that still define the golf world. His portraitist here is Frank Hannigan, who began his career as a golf columnist for the Staten Island Advance before joining the United States Golf Association as public-information manager in 1961 and eventually rising to become its senior executive director, 1983-'89. He subsequently worked as an on-air rules commentator for ABC and a columnist for Golf Digest.

Hannigan was a writer at heart and bureaucrat by accident. He believed in jazz music, the Rules of Golf and the joy of friendship—and those three principles guided his life. Hannigan also admired power brokers and Old Money elite; he loved observing them up close, the way they wielded influence and got things done. He was personally dismissive of Augusta National—refusing to go to the Masters in his later years—but I always thought it was out of a touch of envy for what the institution has come to stand for. Despite or maybe because of his contrarian nature, Frank saw Roberts as a mix of pure power and to-hell-with-everybody-else. They were two iconoclasts separated only by a bank account.

This story should be compulsory reading for modern sports administrators and tour pros who need to appreciate where the game came from and who got it here. Pretty much nothing has changed since this piece was published in April 1996, except Masters daily tournament tickets have gone from $100 then to $115 in 2020. —Jerry Tarde

During the morning of Sept. 29, 1977, a very sick old man put a pistol to his head and concluded his life at the edge of Ike’s Pond on the Par-3 Course of the Augusta National Golf Club. The deceased was Clifford Roberts, 84, whose twin legacies were the Masters Tournament and the property where he chose to die.

Bobby Jones, the ultimate gentleman amateur golfer, is beatified anew every spring at Augusta, but it was Roberts, initially as Jones’ silent but strong partner and eventually when the crippled Jones was only an icon, who converted the Masters from a pleasant Southern respite into one of the grandest events in sports.

Darren Carroll

Roberts’ accomplishments were incomparable. He created, nurtured and assured the permanence of a huge occasion without the endorsement of any organization in his sport, nor with a link, or obligation, to any player or group of players.

The secret of the Masters is its independence. The people who run it can do whatever the hell they want. Decisions are not based on money. (This is not to say the Masters does not make money. It makes more than plenty, but not nearly as much as it might.) Meanwhile, as sports—including golf—become more crass and greed-driven, the anomaly of the Masters grows more appealing and compelling every year.

In a time when sports franchises bounce from city to city to assure that an owner’s grandchildren will not have to work for a living, it’s a blessing that the Masters flows on without corruption of corporate hospitality tents and with the cheapest (if toughest to obtain) tickets in big-time sports—$100 for all four days again this year.

Roberts was certainly not a dashing figure. He was button-faced and somber—American Gothic. His manner of speech was memorable only for its monotony. He wore a variation of the same blue suit every day and owned 24 identical rep ties. Life was too short, he said, to worry about what to wear. He was altogether unremarkable except that, better than anyone else in golf, he understood power—how to acquire, use and retain it.

Take, for example, television. More than any single factor—the azaleas, Rae’s Creek, the dogwoods, even the eternal blessing of Bobby Jones—it is the cleanliness of the television presentation that has distinguished the Masters with its hugely effective subliminal message: “This week is splendidly different.”

The Masters was first televised in 1956. CBS has always been the network carrier. Roberts deeply distrusted television because it had the inherent power to determine the reputation of his passion.

By the 1960s, he figured out that the way to deal with television was to allow it to speak only when spoken to. He adopted the terroristic tactic of the one-year contract. No other owner of a hugely valuable sports property does one-year deals. Roberts did because it meant he could pick up and leave whenever he pleased, comfortable in the knowledge that NBC and ABC would kill to replace CBS.

He, not the network, decided who the sponsors would be, what they would pay, how much commercial time they would get, and how the parties to the arrangement, including CBS, would divide any profits. (It helped, of course, that he had made the CEOs of the TV sponsors members of Augusta National.) The trade-off for dictating the terms was simple: The contracting parties made less money. It is an option available, but never used, by the managers of all other big-time events. Augusta accepted as a TV-rights fee about half of what the United States Golf Association was getting for its package of national championships, including the U.S. Open.

Roberts had a vision of a commercially uncluttered telecast with just enough quiet selling to pay for the thing. He ordained there would be only four-one-minute commercials per hour. Moreover, the network affiliate stations would be denied the precious one advertising minute they are afforded in all other network sports telecasts. Four minutes of commercials an hour in television feels like a high mass. By comparison, the USGA goes away from golf 8½ minutes an hour during its U.S. Open shows. Network telecasts of PGA Tour events have to tolerate as much as 15 minutes an hour.

Picking a proper dignitary

When Roberts decided that Augusta’s commercials would be slashed, he also ordered CBS to begin its telecasts with an announcement about his policy. He further dictated that this on-camera announcement would have to be made by someone unique to the golf audience, not by a familiar CBS sports announcer.

Roberts actually had the gall to suggest in 1966 that CBS send down Walter Cronkite to do this brief paean. Cronkite was no less than the most trusted man in America and, as such, unaccustomed to hyping sports events. CBS gulped and said Cronkite was not available. The network made a counteroffer to the industry’s most visible entertainment host, an avid golfer and ex-caddie—none other than Ed Sullivan. Roberts’ frosty reply, for the ages, was “Hell, no. Sullivan uses monkeys on his program.” Ultimately, Jim Jensen, the local news anchor for New York’s WCBS, was brought in for the special function, but not before Mr. Roberts also failed to entice the ultimately urbane Alistair Cooke.

Roberts knew next to nothing about how television worked (he would periodically praise CBS faintly for providing “nice, clear pictures”), but that did not stop him from sending detailed critiques to William McPhail, then head of CBS Sports, in which he reminded poor McPhail that the Masters was a big deal long before CBS was allowed to despoil the premises.

Roberts became angry when, on a dreadful weather day, CBS had inadvertently showed some sodden bits of paper on the grounds (“The public at large must have gained the impression that the whole affair was a most untidy event”); he told McPhail that the raised pieces of ground in the par-5 15th fairway were “mounds,” not (ahem) “humps”; and he was livid when CBS sent a helicopter over the course to take aerial footage during a practice round without clearance. He described the incident as a kind of 1964 precursor to “Apocalypse Now,” claiming his patrons experienced “discomfort” (and illness in some cases) caused by the “pine-tree pollen stirred up by helicopter.” His own discomfiture was heightened by learning CBS had experimented with such aerial views of holes at a godforsaken tour event. All innovations were supposed to be revealed at the Masters.

Roberts, with Jones 100 percent on board, wanted television reverence, but they were not averse to wit. In fact, the great English announcer Henry Longhurst learned he would be on the commentary team at Augusta when he was so advised by Roberts in a note saying the Jones-Roberts pair had “informed” CBS they wanted him. The handling of television—dictatorial, innovative, but with good taste—was symptomatic of the staging of the Masters.

Innovative and stubborn

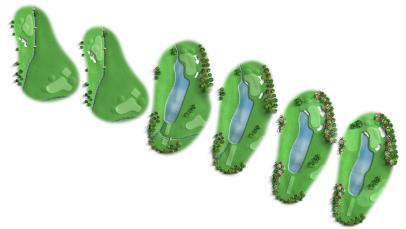

Augusta and the USGA began using on-course leader boards simultaneously in the late ’50s, but it was at the Masters where the radical idea of having the boards display the players’ standing with relationship to par, rather than in total strokes, was first used in golf.

The Masters was first in this country to set out sizable grandstands; the first to install signs at all tees showing each player’s score as he passed by; the first to distribute free daily printed pairing sheets free of ads; the first to impose a limit on ticket sales, and the first to remove the old dread from spectators by installing decent toilet facilities far removed from the clubhouse.

Roberts understood less is more, that drama is enhanced by focusing on the players, not the flotsam of golf officialdom. So he allowed only players and caddies to be visible inside the gallery ropes. He disdained volunteer marshals who insist on becoming part of the spectacle with their hideous “Quiet Please” signs and instead paid Pinkertons to do crowd control discreetly; he refused to allow reporters and photographers inside the ropes, and he insisted on the development of an invisible scoring system that does not rely on the ludicrous spectacle of volunteers in purple uniforms barging down the middle of fairways rattling clipboards.

Roberts did not personally divine all these novelties, but listened carefully to counselors who understood what the man wanted and who, like him, were not in it for the money. Roberts paid his own expenses at Augusta National, including the cost of his room and food. He lived at the club about four months a year. The club menu was adjusted to his presence. It must have been the only club in America where you could not get french fries with a hamburger, Mr. Roberts having concluded french fries were unhealthy.

Needless to say, he could be stubborn. USGA Executive Director Joe Dey had warned him that having only an umbrella table behind the 18th green, where players returned their official scorecards to an inexperienced Augusta National member, was dangerous. The USGA had been burned at a Women’s Open in 1957, when Jackie Pung returned an erroneous card at an unprotected umbrella table. Thus, the 1968 Roberto De Vicenzo scorecard disaster at the Masters happened both because Roberto was careless and because there was nobody there to insist on cross-checking the cards.

The next year, the umbrella table was replaced by an olive-drab tent big enough to house an infantry platoon. It was manned by a PGA of America official, Joe Black, a great rules personage, who was assisted by a certified public accountant. Asked in his 1969 pre-Masters press conference, an annual 30-minute drone, what had been done to improve the 18th-green scorecard situation, Roberts looked the questioner right in the eye and said they were doing nothing new.

A Wall Street hotshot

Roberts was able to devote so much time to Augusta because he made lots of money early as a Wall Street broker. He was a partner in Reynolds & Company, having bought 15 percent of the firm in 1921 after a hot run buying and selling east Texas oil leases as a youngster of 27.

Born on a farm in the hamlet of Morning Sun, Iowa, in 1894, Roberts was the second of five children. The family moved to Texas, Kansas City and San Diego. His father sold real estate. After graduating from high school, Cliff found work as a traveling wholesale clothing salesman. He was good at it.

At Reynolds & Company, Roberts was a 1920s Wall Street hotshot who took a huge hit in the 1929 financial markets crash. He bounced back to become one of the largest producing stockbrokers on Wall Street. His most profitable account was General Motors, which was headed by his great friend Albert Bradley.

With early members like Coca-Cola’s Robert Woodruff and Alfred Severin Bourne, who had the good sense to inherit the Singer Sewing Machine empire, there was enough money for Augusta National to get started in 1931, a year when golf clubs were being shut down by the hundreds. But Augusta National was at first a very Southern institution, replete with FOBs (Friends of Bob) who were by no means all rich and powerful. Women—in any event, wives—were out of the question. If the truth be told, the Augusta National of the 1930s was a swinging place for good old boys who were very much inclined to behave like boys away from home. The club became much more sedate when Roberts, after World War II, enticed members into financing “cottages” (actually large houses) suitable for guests on the grounds.

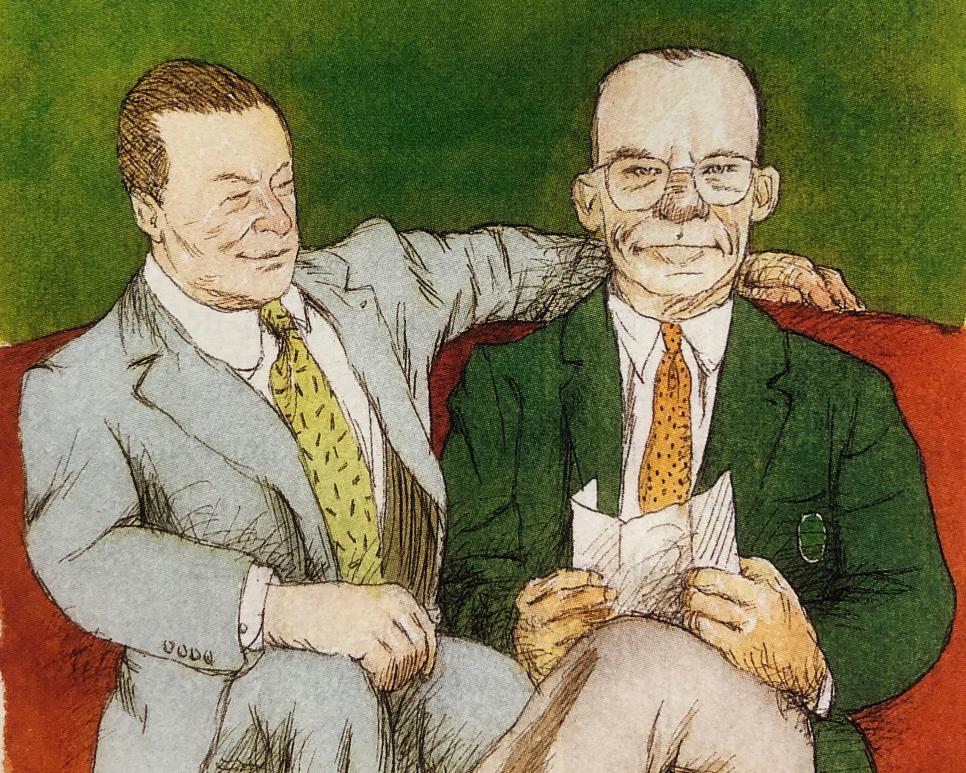

Roberts cultivated Jones in the 1920s after they were introduced by Walton Marshall, who ran the Vanderbilt chain of hotels. It was Roberts who discovered the old nursery property in Augusta and proposed its purchase to Jones, who very much wanted to create a golf course after his retirement from competitive golf at age 28 in 1930. Jones was president of the club from its inception and remained so, at least nominally, until his death in 1971.

Roberts handled all the details, but nothing was done without Jones’ approval. Roberts, from Day One, wanted to call their new event the Masters, but Jones said no. Too pretentious. It was launched as the Augusta National Invitation Tournament, with Roberts lobbying constantly for the catchier name. It became the Masters Tournament formally in 1938.

Jones was stricken with an incurable spinal disease in 1947. He deteriorated gradually but inexorably; he was able to tolerate the two-hour trip from his home in Atlanta to Augusta less and less. Although Roberts talked to Jones often, and copied him on everything, the preeminence of Roberts in the relationship was inevitable as Jones declined.

Roberts, with a rubber-stamp executive committee, picked the members. Increasingly, there were fewer FOBs and more tycoons. Jones, when asked to approve the latest batch of Fortune 500 barons nominated for membership, replied to Roberts, “About all I can say is that you appear to have picked a group of individuals who are thoroughly solvent and should be able to pay their dues.”

One of the reasons Roberts liked CEOs was that they came equipped with corporate aircraft that he played with like Tinker Toys—dispatching them hither and yon to deliver people to the Masters whose presence he deemed useful. When USGA President Phil Strubing told Roberts he would not be at the Masters in 1970, Roberts simply sent somebody’s corporate jet to pick up Strubing at Sea Island on Sunday afternoon near the Strubing home, zip him to Augusta so the world could see the USGA was properly represented at the green-jacket ceremony, and then take Mr. Strubing home.

Means of seduction

During the 1960s, the Masters became more than a golf tournament. It blossomed as the annual convocation of golf’s ruling elite who, by the way, were welcomed as members in increasing numbers. From 1946 to 1980, 11 of 18 USGA presidents signed on; in 1965, more than half the members of the USGA Executive Committee were delighted to be conscripted. Indeed, I had a friend who campaigned eagerly to get on the USGA board because he saw it as the quickest road to Augusta. (USGA board membership no longer cuts it at Augusta National.)

Roberts was also an effective seducer of print media. When he decided the Masters needed to be worldwide in renown, he enticed overseas reporters. The golf writers for the establishment British newspapers (the Times, Telegraph, Guardian, Observer, etc.) were advised that if they could get themselves to New York City, the rest would be gratis. Another of those lovely corporate aircraft (no doubt written off as a business expense) was laid on in New York. At Augusta, there was a house, a car, food, drink and servants.

Roberts was a selective hero-worshipper. His two primary heroes were Jones and Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, who became a member of Augusta in 1948 at the behest of Bill Robinson, general manager of the then-powerful New York Herald Tribune newspaper. An Augusta-centered inner circle urged Ike to run for the presidency in 1952.

It was Roberts’ job to raise the money needed to fund Eisenhower’s candidacy. Roberts also managed Eisenhower’s personal money. Eisenhower, who had no money to speak of after World War II, wanted assurance from Roberts that the money would be raised “on the up-and-up.” Roberts assured the general it would.

A need to be No. 1

Roberts was inordinately proud of the Eisenhower relationship, which he typically and obsessively converted into one of the endless statistics he produced to prove that the Masters and Augusta National were No. 1. Eisenhower, Roberts later wrote, paid 28 distinct visits to Augusta National while in office.

Eisenhower listened carefully to Roberts but was by no means in constant agreement. Roberts, for example, urged that Richard Nixon be dumped as Ike’s vice-presidential candidate in 1952, after allegations about an earlier Nixon slush fund.

Roberts commissioned an annual count of the number of words filed by telegraphers from the Masters pressroom to compare with that of the U.S. Open (his side won); and it mattered enormously to him that the Masters have the highest golf television rating even though Nielson ratings are irrelevant to the majesty of the Masters.

He once called me, when I was a USGA bureaucrat, to lament a PGA of America decision to play its PGA Championship in February 1971, a desecration to him because it meant the Masters, that one year, would not be the year’s first major. The call must have lasted 45 minutes, and I still have no idea why he called me, since (a) there was nothing in the world I could do about it, and (b) I couldn’t have cared less.

The reason Masters attendance figures have never been revealed is Roberts knew he could not be proclaimed tops in attendance, even though he was, because he would be trumped by a lie. If he announced, “We’ve sold 35,000 tickets, our maximum,” he would painfully hear on television that somebody else concocted an attendance of 40,000.

Compulsion and racism

The man’s compulsion for endless detail and his need to control were epitomized in a memo he once sent to accompany the club’s annual gift to selected VIPs. The gift was an address book with an Augusta-green cover. With it came this advice: “You will find that about 20 percent of your friends will annually change their address or phone number and then erasing becomes necessary; therefore, entries should not be made except with a pencil. Always use sharply pointed hard-lead pencils (No. 3), as soft-lead pencils will smear. . . . You will need to list quite a bit of data in limited spaces, so I advise you to print rather than write . . . To me, the handiest place to carry an address book is in my left breast coat pocket.”

Roberts’ reputation has been tarnished by post-mortem accusations that he was a racist. Last year an HBO Sports special drew attention to itself by saying the Masters stacked its invitation deck so as to preclude the presence of Charlie Sifford during the 1950s—an accusation rightly denied by Chairman Jackson T. Stephens, who then got carried away in saying, “There was not a prejudiced bone in [Roberts’] body.”

Roberts, in truth, was part and parcel of a racist culture. He thought that loyal blacks, including Augusta staff, should be cared for decently—so long as it was understood they were servants or entertainers. A primary example was the prizefight champion Beau Jack. He began as an Augusta National shoeshine boy, was sponsored as a fighter by a cluster of members and eventually reverted to being a shoeshine boy. Roberts, a confidant of the president of the United States, thought there would be trouble in both the United States and England wherever people of color converged in large numbers. Roberts by no means confined his suspicions to skin pigmentation. He regarded shortened Italian names as evidence of sinister behavior.

But to distinguish Roberts and his institutions as peculiar for their time is absurd. There were no African-Americans in high office in the USGA until the Shoal Creek debacle of 1990 provided an impetus; the PGA of America had a “Caucasians only” membership clause until the attorney general of California threatened to throw the PGA out of the state in 1962, and Jews were not acceptable in the hotel of the Pinehurst Country Club more than a decade after World War II. Roberts was no Branch Rickey, but neither was Bobby Jones.

The strangest of exits

Roberts aged awkwardly. Content with having been the ultimate behind-the-scenes eminence so long, he became more visibly cantankerous, concerned with getting his version of history on the record. He even wrote a memoir (published by Doubleday & Company after Nelson Doubleday was made a member) in which he revealed nothing except that his 80th birthday party at the club was a gala occasion.

The strangest and saddest thing happened to his relationship with Bobby Jones, although Roberts’ admirers insist his adoration for Jones never ceased—that every act he took at Augusta was to further the reputation of Jones.

But Jones’ son and daughter-in-law became furious with Roberts, whom they saw as having treated Jones with disrespect.

There were reports Roberts was petty enough to refuse extra Masters tickets to Jones. A more credible story is that Roberts decided personally to remove Jones as host of the televised green-jacket ceremony but blamed CBS. Jones was then so frail he could barely keep a cigarette holder in his hands.

I think it more than likely that Roberts could not deal with the emotions of telling Jones directly that his time had come. In any event, Roberts was not invited to attend Jones’ funeral in December 1971.

A primary problem with totalitarian societies is that of succession. Roberts intended to control the future by naming his successor. His choice as tournament chairman came as a surprise. In 1976, he picked relatively young Houston businessman Bill Lane, who was handsome and charming but by no means a golf expert. Roberts retained for himself the club chairman title, which meant he was still very much in control. Roberts introduced Lane to the world at his annual press conference but would not allow Lane to field any questions.

Lane did get to run it all when Roberts was gone, but only briefly. Lane was crippled by a stroke in 1979. The job was passed on to Hord Hardin, who had all the golf savvy in the world but had been regarded by Roberts as inadequate to run the club because he was not a business powerhouse. Roberts was wrong. The club and the tournament thrived during Hardin’s tenure.

Roberts’ health failed after he passed 80. Cancer. He went to the best and most expensive institutions of health—the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, the Lahey Clinic in Boston.

Eventually, he could not abide the loss of independence and control. His mother had committed suicide when he was 19, and he decided to do the same, but not before getting a haircut in the club’s barbershop on the morning of his death. The weapon, a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver, was confiscated by the club’s security force and then, gruesomely, found its way into an auction catalog of golf memorabilia. The asking price was $15,000. The club re-acquired the gun.

His estate was considerable—many, many millions. Half went to his third wife, Betty Lister Roberts. There were no children. The balance of the estate went to charities that had as their goal controlling the growth of population that he saw as the preponderant threat to the world.

Clifford Roberts was a singular man.