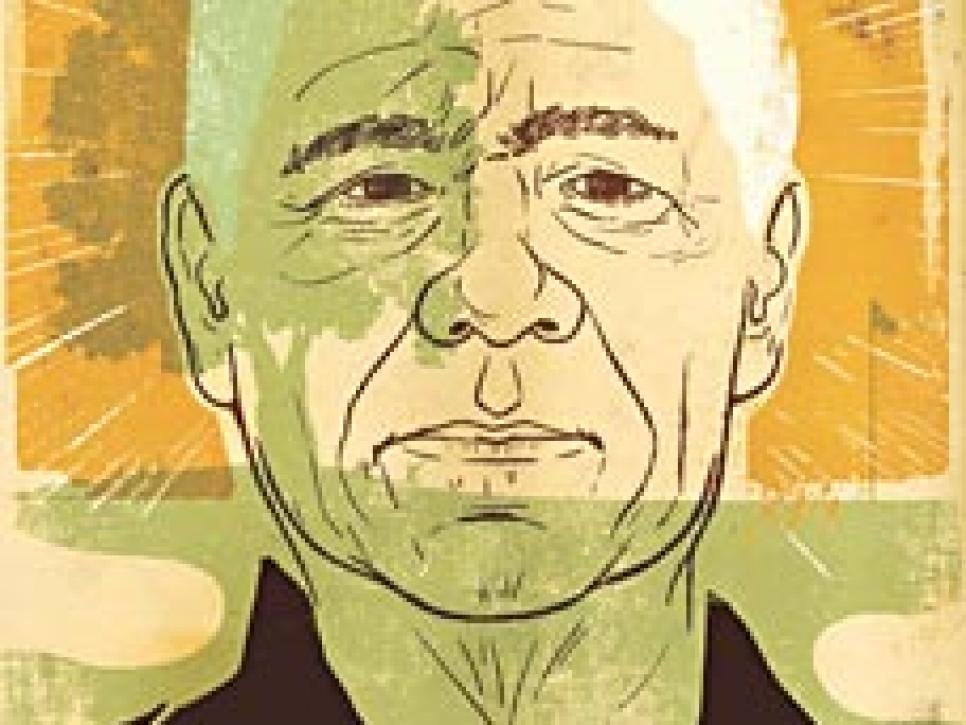

The Third Side Of Lee Trevino

"Where you been?" boomed Lee Trevino as I rounded the corner of the clubhouse. "You're five minutes late. I could DQ you right now!"

Lee cackled and sat upright in his golf cart. He put down his USA Today, removed his reading glasses and reached for his bottled water. "You get lost?" he asked.

"Bad traffic and then a wrong turn," I said. "You give lousy directions."

"That means nobody else can find me, either," Lee laughed. He slid behind the steering wheel of the cart and motioned for me to sit next to him. "Come on. I'll take us down to my favorite spot where nobody can bother us. We'll talk some golf."

Lee was doing me a favor this warm July morning in 1999. He had agreed to do a story for Golf Digest with me as the writer, and he was coming through on short notice. A month earlier, my 4-year-old daughter had been diagnosed with medulloblastoma, a malignant brain tumor as cruel as it is rare. Surgery was performed within 12 hours, and the results were ghastly. To get all of the tumor, the neurosurgeon was forced to sever cranial nerves. The left side of my baby girl's face was now paralyzed, and so were her left arm and leg. The prognosis was difficult, and the worst was to come: 31 radiation treatments on her brain and spine, followed by a year of chemotherapy. After that, I was told, you cross your fingers and pray, because a recurrence of medulloblastoma means the end.

I was calling on Lee because I didn't want to get on an airplane, not with my daughter being in tough shape and my wife as shattered emotionally as I was. Lee and his family spent a lot of time at his mother-in-law's house in the middle of Wethersfield Country Club, a convenient 30-minute drive from my house in Connecticut. I'd worked with Lee on articles many times before, and after I explained the situation to Chuck Rubin, Lee's agent, Chuck arranged for me to see Lee within a week.

To this point I'd seen two sides of Lee Trevino. The first was the public side we've all seen, the wise-cracking, witty, high-strung harlequin who entertained galleries like no one before him. But he also had a darker side when people wrongly assumed that his Everyman persona was an invitation to treat him like a first cousin. Lee could be snappish to people who pulled at him the wrong way at the wrong time. If someone shoved a program in his face and demanded he sign it, or cut him off when he was walking to a range or clubhouse, or asked him a silly question at the wrong time, he would verbally cut them off at the knees.

There were hints that Lee had a third side that not many people had seen. When his longtime caddie, Herman Mitchell, developed heart problems and was no longer able to work, it was rumored that Lee had paid for his care and recuperation and had even given him a place to live. When asked, Lee would give an update on Herman, but he would brush his benevolence aside. He just wouldn't talk about it, even when reports of him helping others in the same way came to light.

Lee wouldn't let many people inside. The first few times I met with him at Wethersfield to do instruction pieces for Golf Digest, he was all business. He was cordial enough, but when we had finished and he'd been dropped off at his mother-in-law's house, that was it. There was no more small talk and no offering us something cold to drink. But one day, after we'd wrapped up a story on driving -- and I'll add here that no player I've ever seen hit the ball better than Lee Trevino -- Lee invited me inside. He gave me a tour of his basement workshop, showed me how he'd tinkered with the many sets of irons and scores of rare and valuable Wilson 8802 putters that were in a barrel down there. He made sandwiches. On the way out, he shoved several dozen balls and a handful of gloves at me. A few months later, when I saw Lee in Florida, he invited me out to his car. "I want to show you something," he said, and when we got there he popped open the trunk and handed me a Wilson 8802.

"I've watched you putt, and you need a good putter like this," he said. I'd earned his trust and friendship at last.

As Lee drove the cart down the hill from the clubhouse that day at Wethersfield, he gave no inkling he knew anything about the circumstances surrounding my daughter. He didn't say much as he parked the cart under a large oak tree on a remote part of the course. "Now, what's this story we're doing about?" he said.

"The idea is for you to identify the best players you've ever seen in every department of the game," I said. "Best driver, best iron player, best sand player, best putter, and so on. Let's start with the best driver. You once told me Greg Norman is the best ever. You still believe that?" I turned on my tape recorder, the signal for Lee to start talking.

But Lee didn't say anything. After a moment I looked up at him expectantly, but he just stared at me. Then he reached down and turned off the tape recorder.

"I hear your kid is sick," he said.

"Well . . . yeah," I said awkwardly. "How did you . . . "

"Cancer, right? Brain tumor?" he said, his eyes narrowing.

"Yes."

"Maybe you should send her down to St. Jude's in Memphis. Has she been treated yet?"

I explained the surgery, and that her first of the 31 radiation treatments had taken place only a few days earlier.

"Listen," Lee said. "St. Jude's is the best. Everything they need to treat these sick kids is right on site: surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, physical therapy, everything. The families actually move down there while this goes on. And it's free. St. Jude's is the best, but they have one rule: They want the kid from the minute they're diagnosed. If you're in the middle of treatment somewhere else, they won't take you, because they want to treat them their own way and track them from day one. They never violate that rule."

"Well, I guess we won't be going to St. Jude's," I said.

Lee put his arm around me. "I want you to know something. My whole career, I've had only one charity, and it's St. Jude's. I won the St. Jude's tournament three times, and I've done a lot for them down there. I don't talk about it, but let's just say I've done a lot for my favorite charity over the years."

Lee's eyes started To well up. He hugged me tighter.'

Now Lee's eyes started to well up. He hugged me tighter. "I don't know if you're happy with the care you're getting up here or whether you have good insurance. Treating cancer isn't cheap. But listen: If you want to take your kid down to St. Jude's, I'll make a phone call. I'll ask them to help us. They have that rule, but if they don't break that rule for me after all I've done for them, well then, they've lost Lee Trevino."

I broke down over that. All of the fear and tension I'd concealed over the last month to be strong came pouring out of me. In that time of crisis, many people had rallied with support. But having Lee Trevino on my kid's side was something else again. For him to stick his neck out like that, and immerse himself in something so unpleasant for someone he saw twice a year, was profound. At that moment, under the shade of that big oak tree, Lee was like a spiritual being. All the energy, determination and force of will that had lifted him from abject poverty to become one of the great athletes of all time was now focused on my sick child. He exuded power, understanding, kindness and anger at the injustice of it all. I'd known about the two sides of Lee Trevino, and now I was experiencing that wondrous third side. Lee was transformed into a warrior angel eager to lift a terrible, swift sword against something evil, with all his might and no reservations.

"We'll get her better," Lee murmured, patting my shoulder, "We'll get her better. There now, partner, it'll be all right. We'll get her better."

It wasn't necessary for me to call Lee, and who knows if St. Jude's could have accommodated such an awesome request, even from him. My daughter survived, and despite some scares and setbacks, is with us still. Today, with sufficient time having passed that I can look back on those first dark days without my stomach churning all over again, I realize it wasn't just luck and the skill of many doctors that helped my child and our family survive. Prayers helped, too, and I've always believed that the magical third side of Lee Trevino was the greatest prayer of all.