News

Changing The Cycle

'I've moved away from the parties. You know, around here, there's one every night if you want it... If I don't have one more party for the rest of my life, I'm still ahead of the game.'

Twenty years ago, I sat down with 22-year-old Ernie Els in the Johannesburg offices of Sam Feldman, the first in a long, gray line of Ernie's agents. Els had yet to play in either a Masters or a U.S. Open but had won everything at home. "People may go 'Ooh,' " he told me, "but I like a beer with my friends."

After Els won the 1994 U.S. Open at 24, I asked Payne Stewart how Ernie was getting along at Lake Nona in Florida. "He's had a beer," Stewart said, laughing, "with every member of the club." Payne meant it, of course, as a compliment.

In the rollicking or, more often, mean-spirited whispering around Els and alcohol ever since, a pertinent piece of information has been left out. It's what begins to explain the change in Ernie this year that was at least a factor in his triumph at Royal Lytham & St. Annes:

If not for courage against drink, Els would have been a rugby or tennis player. He would never have been a golfer at all.

In a culture of alcohol on the hard side of South Africa, Ernie's dad, Neels, had a better excuse for drinking than most. Neels' father died of cancer at 43, calling him at bedside to the brutal transport (trucking) business and placing six younger siblings in his care. He was 18. ("To take over that business at that age," Ernie says, "can you imagine?") The youngest child, a 4½-year-old boy, was run over by a car and killed in front of the house. Their mother was never the same after that. She died at 50.

"You need a new hobby," Ernie Vermaak, Hettie's father and Ernie's namesake, told Neels, dragging him to a driving range. He had never given golf a thought. As a boy, he stuck to men's games. "But I started to enjoy it," he said, "so much more than drinking."

That was the beginning for Ernie Els. On Dec. 12, 1969, 56 days after Ernie was born, Neels had his last drink. "I made a promise to God," he told me by a practice putting green in 2002, "and He gave me something back. He gave me Ernie."

"Really," Ernie says softly. He hadn't heard that before.

It's three weeks after Lytham. We're sitting at Els' Florida headquarters in Jupiter, just around the corner from the Bear's Club. The claret jug is on the table between us. "Wherever I've gone, I've put it on the table," he says, "and we just kind of stare at it."

Neels "changed the cycle," as Ernie puts it, "and he's a better man for it. My dad is just an amazing, amazing human being. For myself, for my family and for my future, it's better for me to change the cycle, too. It was always in the back of my mind, you know--it's in your family--but I can't say I ever really worried about it. Never. For all the fun, don't forget, I always knew when to put my golf balls down and practice. I'd say I'm just at a different stage of life now. I'm older. I've moved away from the parties. You know, around here, there's one every night if you want it. In my 20s, I probably would have been there 80 percent of the time. But I'm in my 40s now [43 in October]. I've got my life. I'm very serious about my business. I've got my family. And I've got my game. Excessive drinking is not good for my health, my family or my game. There has definitely been a change, and I feel better for it. The boys from the club will say, 'Come over Friday and we'll have a couple of beers.' 'No thanks; I feel too good. I want to go practice. I want to be with my kids.' If I don't have one more party for the rest of my life, I'm still ahead of the game."

He laughs at that.

Truth be told, the fellowship, not the booze, was the allure.

"Even before I turned pro," Els says, "when I was an amateur in the Army with Gary [Gary Todd, a long-standing friend], we had such unbelievable times, great times. But I would say we were a fun group. We weren't angry drunks. We liked to laugh. Not to get pissed off at life and go nuts."

Throughout Ernie's pro years, many players have shared his airplane and Heinekens. "Adam Scott traveled with me around the world," he says. "We could write books on the stuff we did. But fun stuff. I'm not talking about seedy crap. Just fun, almost like boy stuff." But he is not a boy anymore.

Typically, Els regrets the false message conveyed to young golfers, especially the kids back home in South Africa. "They see me as this big drinker," he says, "for whom everything was automatic, who just showed up from South Africa and was given all the money and fame without working for it. It doesn't happen like that. You have to practice. You have to train. You have to work yourself almost sick. It's a hard life--a great life, but hard. Nothing is given to you."

That also came from Neels, who never expressly told Ernie to work hard. He showed him. As a primary-school student, Ernie listened to his father in the next room, liquidating one company (giving all the money to his brothers and sisters), starting up another from scratch. He could hear the worry in his father's voice and feel the tension at the dinner table. "My dad is the hardest worker I've ever known, and without telling me what to do, I could just sense, You go to work, Ernie, if you want to get anywhere. And being The Big Easy, the soft guy, the drinker, the partier, I still never forgot it's hard work that gets you a little bit of the reward. And now that I've figured out that less alcohol will give me a better chance, too, that's what I'll do."

'I THOUGHT I WAS COMING TO A PREMATURE END'

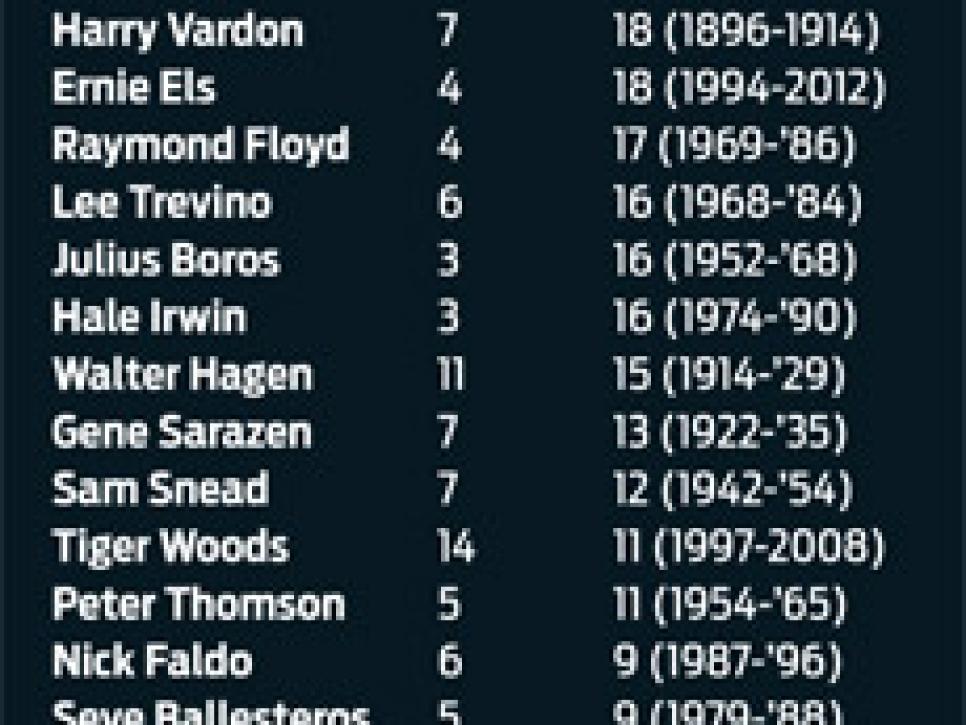

The happiest part of Els' fourth major is the 18-year window between his first and most-recent, a stretch thrice the length of Arnold Palmer's and, for the time being, Phil Mickelson's. Majors in three decades stamp a champion as one of the best things a champion can be: durable.

"I thought my window had closed," Ernie says. "Yeah, especially considering the state I was in last year. A bad kind of state. I was a different person. It was a bit of a confidence thing, but I thought I was coming to a premature end."

Even for one so well-acquainted with disappointment, the 2010 U.S. Open at Pebble Beach was bitter. "After messing up there," Els says, finishing third, "something inside of me just went. That tee shot I hit at 10, and not making anything [on the greens] the final day, drove me crazy. My family saw me afterward, and I was livid with myself. After that U.S. Open, if you look at my performance, I was gone. Over the edge. That's when my putting problems came. That's when the doubt--the really serious doubt--hit me."

Being inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame, as sweet an achievement as that was at 41, probably didn't help. As he says, "You meet these greats of the game who were way before your time [like 90-year-old fellow inductee Doug Ford] and say to yourself, Wait a minute, I'm still a youngster here. Obviously this is where you've always dreamed of ending up. And it's such an unbelievable honor to go in young. But, looking around the museum, I thought, OK, you're in the Hall of Fame. What now?"

Another good question: What makes a man who has all the money in the world keep placing himself in a position to, as Ernie says, "get kicked in the ass over and over and over again?" Maybe Greg Norman or Tom Weiskopf would know about this. "There have been so many majors that got away," Els says, "starting at Riviera in '95, taking a three-shot lead into the final round of the PGA and not winning. You know, you see all these ads, you see all these movies, where the message is, 'Stick to it.' 'Stay with it.' But, after so many near-misses, how do you do that? What is it that makes you get up again, pull your ass into the gym again? Now, go hit golf balls again. I think that's the great question of sport. What keeps a man going?"

The answer is on the table.

Photos: Getty Images

He glances at the silver trophy, engraved with the names of Willie Park, Old and Young Tom Morris, John H. Taylor, Harry Vardon, James Braid, Ted Ray, Jock Hutchison, Walter Hagen, Jim Barnes, Robert Tyre Jones Jr., Tommy Armour, Gene Sarazen, Henry Cotton, Sam Snead, Bobby Locke, Ben Hogan...and Ernie Els twice. Els shakes his head and says, "It's amazing how this game and life reward you if you can just stay with it."

At the beginning of 2012 when, as Ernie says, "I was so unbelievably low," Dr. Sherylle Calder appeared. She is a South African "vision performance and skills specialist" known for her work with the Springboks rugby team. Nelson Mandela calls her "the Eye Lady." In his imagination, Mandela played for the Springboks in a prison cell for 27 years, the last 18 of them on Robben Island.

"I knew Sherylle since 2003, through the Springboks," Els says, "but we had never done any work. We spoke for 10 minutes and then got together for two days before Fancourt [the Volvo Golf Champions in South Africa last January], where I lost in a playoff. So I went from nowhere to almost winning. I know it was a weak field and so on, but it mattered."

After their first putting session, Dr. Calder informed Ernie his head and eyes were not just out of sync. They were all over the countryside. Two days later, she told him, "You're going to win a major this year."

"But, just two days ago, you said I was the worst case you'd ever seen in your life."

"Yes, but that was then."

That was then.

"Now, just imagine how you're going to improve."

Ernie says, "That gave me so much belief. For the first time in I don't know how many years, somebody was telling me, 'You've still got it.' It's nice to have somebody believe in you."

Twice a day, she has him on a computer, whirring and whizzing through exercises designed to brighten the eyes and bolster concentration and motor skills. "Numbers pop up on the screen," he says, "and you have to memorize them in a split second. You can hardly bloody see them. A lot of stuff is going on all at once that you must react to and remember. A blue ball changes into a red ball changes into a yellow ball...focus, man. There are like 30 levels, and then you move on to a new program. It locks me in, helps me block things out. I think it's improved my distance control. And I'm sure I see my lines better."

All science and colored balls aside, her real gift is Vince Lombardi's old gift. Reinstalling self-belief in great athletes is a sublime skill. Especially pro golfers, who are essentially alone and rely so fundamentally on their faith in themselves. Of course, they have to be open to it, like Els. If you tell Tiger Woods he's going to win a major next year, he'll probably spit on your shoe and say, "Tell me something I don't know." Even though self-belief is precisely what has been missing in him at majors for going-on five years.

"I'm sure other players do similar stuff," Ernie says. "It's not like I'm inventing something. And we've still got a lot of work to do, a lot of improvements to make. I want to get out of the belly and back to the short putter. I want a lot of things."

PRODUCTIVE DAYDREAMING

He was on his own at Lytham, which was unusual. Liezl and daughter Samantha dropped by on Tuesday, then returned to Wentworth near London to watch on television. "When you're on your own," Ernie says, "you watch TV, read, whatever, but for some reason I was daydreaming quite a lot that week. I got to thinking of Seve, and I remembered watching him in '79 and '88." Ballesteros won his first and third Open Championships at Lytham; he is everywhere on the grounds. "The second one was really great for me, as a youngster, because I felt it might be Seve's last chance. If he doesn't win here, I'll probably never see him win another major. As it turned out, that was right. In a way, I felt the same about myself at Lytham [where Ernie previously finished second and third]. That Saturday night, I just felt good about it. I can't explain."

He has a Ballesteros connection, of course. Who in golf doesn't? On Els' way to the first of seven World Match Play titles, in 1994, he beat Seve on the 35th hole of a 36-hole match that still tingles the spine. Between them that day, they recorded 13 2s, seven by Seve. Twice they chipped in on top of each other. Neels was alone in the locker room afterward when Ballesteros came in and sat beside him. "You know," he said, "I tried very hard today. I played very well today. But, your son. Very special." Neels wept.

"Coming to that final nine at Lytham," Els says, "I said to Ricci [caddie Ricci Roberts], 'I'm going to play with passion this nine. I'm going to play like Seve Ballesteros.' We just took the driver and went for it. I pushed my drive at 16, but when we got to the ball, there was a nice little gap between the bunkers. I could have gone the aerial route, but I said to myself, Clip it right through there, like Seve." The shot came off like a prayer, but Ernie missed the putt.

"If we'd have had a hotter putter," he says, "we'd have birdied 11, 16 and 17." But they did birdie 10, 12, 14 and, from some 15 feet away, 18 for a four-under-par 32 on the back and a 68 for the round, by seven (Scott), six (Brandt Snedeker) and five (Woods) strokes the best Sunday score of the contenders.

Did he happen to see a photograph the next day of the ball floating over the 18th cup and...

"And my head's still back," he says, smiling. "Quiet eyes. Quiet eyes."

Championships, and now they each have four major victories.

Photo Courtesy of Ernie Els

Meanwhile, his friend Scott was in the middle of a four-hole nightmare. Ernie and Ricci repaired to the practice putting green but stayed in the game. "In my mind," Els says, "I was preparing for the 6-iron shot I figured I would need on the first playoff hole, getting that picture going. I was busy hitting a chip shot--I was just about to hit the chip shot--when I could hear Adam's par putt miss. I was a bit stunned. Then, looking at Ricci, I thought, He's been here for all four. It's like, in a split second, your life goes in front of you. You look at your guy and see the emotion in his face. It all just hits you, instantly, you know? Absolutely right there. And it's like, you can't believe it. What struggles we'd been through."

Ernie went directly to Scott, put his arm around him and meant it.

Then he waited to hear the prettiest words in golf and carefully listened to each one.

" 'The champion golfer of the year.' Totally unbelievable. I'm the Open champion. Ridiculous."

Finally, he thought of Samantha and Ben. "And I couldn't wait to get home," he says.

Ernie's 13-year-old daughter was too young in 2002 to remember his last major. "Samantha watched with a girlfriend of hers at a golf club in London," Ernie says. "She was the toast of the town, so to speak. All the members came up to her. When I heard about that, I felt so proud for her."

Ben watched with his mother at home. "He'll be 10 in October," Ernie says, "but he's like a 3- or 4-year-old. He's such a character. He won't let you know at first. You've got to just wait around. Then he'll come over. 'Dad won,' he'll say. 'Dad made putt.' That means everything in the world to me."

Liezl once told me that the main difference between men and women is that, when something like autism occurs, the woman says, "What do we do next?" The man says, "What did we do wrong?"

"That's how women in so many ways are so much tougher than we are," Ernie says. "I was maybe selfish when I learned we were going to have a boy. I thought, Perfect. Samantha, the most beautiful, blue-eyed, blond-haired daughter. Now I'm going to have a son. We're finished. Done. And he's going to be a sportsman. I'm going to teach him how to play rugby, whatever, cricket. Then you find out he's autistic, and suddenly you feel sorry for yourself. You can't figure it out. What the hell? What happened here? You're knocked completely sideways. And what Liezl told you was right. 'OK, we're here now,' she said. 'Let's move forward.' But I was like, 'Whoa. Hang on. What just happened?' I wanted to know how and why. What took place at the birth? I was angry. I wanted to blame something or someone. Only years later did I figure it out enough to go forward.

"Ben is such a wonderful boy. He has a great sense of humor and a lovely disposition. When Johann [Johann Rupert, Ernie's South African patron and friend] was introducing me at the Hall of Fame, I was in the back watching Ben enjoying the expressions on Johann's face. He was listening intently. It was so sweet. He loves Johann. Johann laughs right out of his stomach, and Ben loves laughter. He's the most loving human being I've ever met. He has the gentlest touch I've ever felt. Like an angel. That's what he is. An angel."

In his acceptance speech at Lytham, Els remembered Liezl, Samantha and Ben, Mandela, Rupert and Dr. Calder. But he forgot to thank three people.

"In that bloody speech," he says, "I wanted to talk about Seve, and I didn't. But what I really regret is, I forgot to thank my mom and dad."

Oh, but he did. By mentioning Mandela, Ernie honored Hettie and Neels, who in the time of apartheid raised a colorblind child. Their generation didn't love Mandela like Ernie does. The previous generation wished they'd hanged him.

For the last 20 years, I've been teased by colleagues for being such a sucker for Els. Especially since I'm fairly well-known for not falling in love with the athletes. In fact, it's documented. Johnny Bench wrote in his memoirs that he had a dream he punched me and went to jail for it. The next time we were together, on a golf course as it happened, I told him, "John, you should try dreaming of Ingrid Bergman at the top of her game."

There have been two exceptions. Muhammad Ali could make me cry. He still can. And Els.

Anyone who watched him with Scott at the end of the Open might understand a little now. More than for any shot either of them hit, the 2012 Open Championship will be remembered for authenticity and decency, not exactly hallmarks of golf recently.

And, with his five-year exemption, Ernie is training his quiet eyes on the Masters.

__ELS' IMPROVED PUTTING

From eyes to brain to hands__

round of the 2012 PGA.

Photo: David Cannon/Getty Images

Dr. Sherylle Calder didn't have to look at leader boards to know that Ernie Els needed help with his game. "I could see from watching him on television over the last few years that I could help him," says Calder, a South African sports scientist who specializes in helping athletes improve how quickly and accurately they receive and process visual information. When Calder started to work with Els in January, "I told him to give it six months," she says. "The hardest part comes after the first success, when you're trying to break bad habits."

Els spent hours clicking through a series of elaborate online visual tests and drills Calder designs specifically for each athlete she trains. "Most of the coordination in athletic performance comes from the ability to process information visually," Calder says. "If you can train your eyes, brain and body to work together, you can change your performance."

The work wasn't confined to cyberspace. Calder changed Els' pre-putt routine and helped him totally rebuild his stroke. She demurs when asked for specifics--"competitive advantage"--but the results tell the story. Els gave up just more than 41 putts to the rest of the PGA Tour--sixth from worst--in the "strokes gained" statistic last year. This year, he's near the tour average--almost four putts to the good.

"He's reading it better, stroking the ball better and hitting it more accurately," Calder says. "It's a matter of taking what your eyes see, sending it to your brain and getting your hands to respond accurately." And, she says, "We're only 70 or 80 percent of where we can be. There's no limit to what he can do."

--Matthew Rudy