Why Can't We Be Friends?

"I loved it when Jack and Arnie were partners," Gary Player said. "I hated it when they got so competitive, too competitive. But I knew they were both very good men. I just waited the cold spell out."

"I think we do have a rivalry now with Tiger and Phil," said Butch Harmon back when he was Tiger's coach. (Of course, today he is Phil's.) "Part of it is that they are not the best of friends, for whatever reason. It's not like it's an ugly thing. They just aren't buddies."

It's not like it's a pretty thing. During one of Phil's paternity breaks, someone out on the practice range mused aloud, "I wonder what Mickelson's been doing all these months?"

"Breast-feeding," Tiger said.

What follows is the essence of a long-ago essay that once pertained to two and now applies to four.

At the beginning and at the end, they were pals. Palmer, 10 years older, had the easy grace, rolling shoulders and relaxed slouch of a natural athlete. He looked like a prizefighter, a middleweight. Nicklaus, when he arrived, looked like a sportswriter, an unmade bed. Palmer was delivered to America along with the first black-and-white TV sets, and there hasn't been a more telegenic figure in all of the days since. With an L&M cigarette dangling from his lip, he hoisted a country-club game onto his proletarian back, brought it to the people and made it a sport. Even more winning than his compulsion to go for broke was his inclination not to go alone. He took everyone with him that he could carry, and for a while there he was carrying the entire culture. People who didn't follow golf followed him. Nicklaus turned out to be better, but only at golf.

They met as golfers — young man and teenage boy — at a Dow Finsterwald testimonial in Ohio. "I shot 62," Palmer recalls, "and I tried to shoot 62. I wanted to impress him. I was certainly impressed by him." Before anyone else, Arnold could see what was coming.

"In 1961," Nicklaus said years later, sitting before a crowd of interviewers at Muirfield Village, "Arnie came up to me in the locker room at Firestone..."

"I want to hear this," said Palmer, seated alongside.

"He knew I was thinking of turning pro," Jack continued, "and offered to help me in any way he could. [Agent] Mark McCormack came to see me. The prospect of being in the same stable with Arnie was very appealing."

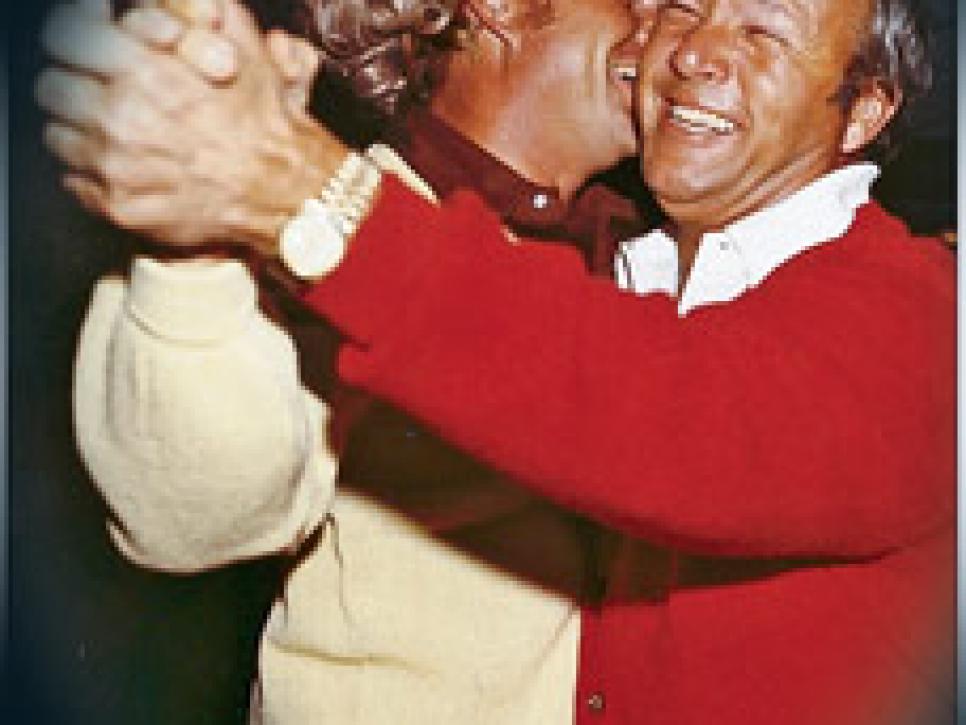

In partnership, buzzing around the world in Arnold's plane, Palmer and Nicklaus won a mountain of international loving cups before McCormack added Player for ballast, and to serve as a kind of third man in the ring. "I can think of the ginger-ale battles Jack and I had in hotel rooms," Palmer said. Nicklaus remembered "one night when we got to kicking each other's shins under the table. I don't know why. I kicked him. He kicked me. Neither would give. We ended up with the biggest damned bruises. We used to do the stupidest stuff."

Trying to pay Palmer a compliment, Nicklaus said, "Before the playoff," meaning their 18-hole playoff in 1962 at Oakmont for the U.S. Open championship, "Arnie came up to me in the locker room and asked, 'Would you like to split the prize money?' What was it, $9,000?"

"I did?" Palmer blinked, probably not as stupefied by the memory of those secret '60s compacts as by the impulse that possessed Nicklaus to bring that up in front of reporters.

"Yes, you did," Nicklaus insisted. "I took it as a gesture made to a young kid. I will never forget it. He has."

Inevitably Palmer and Nicklaus went their own ways, but they stayed connected — hyphenated — like Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney. Waking up to the old truism that "nobody loves a fat man," Nicklaus slimmed himself into a model for clothes and a mold for golfers (towheads shaped like 1-irons), and the spectators quickly forgot that they had ever rooted against him. Palmer stopped winning major championships at the callow age of 34, but 10 years breezed by before anyone noticed. For one thing, he was still in the hunt at U.S. Opens. For another, nobody wanted to notice.

Photo: Ben Winnert

Skipping each other's tournaments without sending regrets, damning each other's architecture with the faintest praise, Arnold and Jack continued bloodying each other's shins under the table, out of the public's view. The writers could see it, though, and sometimes feel it. Pinching the fabric above and the skin beneath the Golden Bear insignia on a reporter's golf shirt, Palmer inquired, "Why are you wearing that yellow pig?"

Looking back, both men would confess to competing so single-mindedly against each other that they occasionally lost sight of the field. A prime example was the '75 Open at Medinah, when Jack and Arnold were paired together on the final day and completely forgot about Lou Graham and John Mahaffey. Golfers don't usually attend each other's postmortems, but Nicklaus and Palmer sat side-by-side in the press tent that late afternoon, delivering their birdies, bogeys and bitter laments. Jack bemoaned his three closing holes so pitifully that Arnold finally had enough. "Why don't you just sashay your ass back out there," he said, "and play them over?" Nicklaus was stunned, slapped. A beat too late, Palmer tossed his muscular forearm around Nicklaus' scalded neck, and they both tried to laugh.

"We didn't always see eye to eye on everything," Jack said years later, "but one thing I'll always be proud of: In important matters, when it came to the tour and the game of golf, we always stood together." By this slender but important thread, when one reached 60 and the other 50, they reeled each other back in. At The Tradition, Nicklaus' inaugural senior event (and first victory), Palmer asked Jack to have a look at his swing. Nicklaus almost fell over. "We had played 30 years," Jack said, "and that was the first time he ever asked me." They started having dinners again, playing practice rounds again.

In 1996, at Tiger Woods' last Masters as an amateur, Palmer, Nicklaus and the 20-year-old Woods played a practice round on Wednesday, Jack's first game with Tiger. That was the day Nicklaus raced from the 18th green to the media center to predict that Woods would win more green jackets than he (six) and Arnold (four) put together. At the par-5 13th that day, the most splendid hole at Augusta National, a figurative handoff took place.

Of course a creek fronts the green there. Popping up a 3-wood tee shot, Tiger for once was away. Facing Nicklaus, whose back was turned to Woods, Arnold peeked over Jack's shoulder and saw the kid pull out an iron for his second shot.

"He's laying up," Arnold whispered.

"Oh, Arnie," Jack said affectionately. "He's not."

Much later, I told Nicklaus, "I think of that as the moment when Arnold realized his class had graduated."

Jack laughed and said, "My class has graduated, too."

PHIL AND TIGER

Unlike Fat Jack, Subcutaneous Phil showed up in better shape than he stayed. But this time the easy grace, rolling shoulders and natural athleticism belonged to the younger man — 5½ years younger — who was the better player as well. People who didn't follow golf followed him. Phil had an athlete's swagger and the guts to try out as a pitcher for the Toledo Mud Hens, even though a watch timing his fastball hardly needed a second hand. Phil's athletic mother said she had never seen a less-coordinated little boy. He walked into so many posts as a child that for a time Mary Mickelson required him to wear a football helmet in the house.

Mickelson is like Nicklaus only in the sense that Phil's tour nickname could also be "Carnac," a snickering reference to Johnny Carson's turbaned know-it-all, who divined the answers before hearing the questions. If you ask him, Jack can tell you the name, rank and serial number of The Unknown Soldier. If you let him, Phil will explain to you the inner workings of the hotel fire alarm. This probably isn't why Tiger has always been put off by Mickelson, or why, early on, Tida Woods took so much joy in the sobriquet "Plastic Phil." Where did Tiger's mother get that?

There's a specific reason Woods has no use for Sergio Garcia. In the clubhouse one day, Tiger saw Sergio standing at a TV monitor rooting somebody's putt out of the hole. Tiger put a hate on him.

In terms of likes and dislikes, Woods has a poker player's obvious "tell." Not since the famed broadcaster and earache Howard Cosell has anyone in sports been so devoted to the diminutive. Like a Valley Girl, Tiger dots his conversation with "Stevies, Weirsies, Steinies, Pricies," and the most recent addition, "Stricks." "Butchie" is what Tiger calls Harmon, which is actually a nickname for a nickname. Butch's real name is Claude.

Yet, to Tiger, Phil is always Phil. Never Philly, let alone Philly Mick. Vijay is always Vijay. And Ernie is always Ernie. Not "Double E," as David Duval used to be "Double D" to Woods. Not "The Big Easy" or just "Easy." ("The Big Easy," you ought to know, is golf's most baldfaced lie since "The Merry Mex.") Tiger certainly doesn't hate Ernie — other than some of his former agents, who could hate Ernie? — but, before heading out with Els to play the third round at Hoylake in 2006, Woods turned to somebody on the practice putting green and said coldly, "If I can break this big guy's heart just one more time, maybe he'll go away and stay away." They both shot 71.

If Els or even Singh had been the one unraveling in the U.S. Open at Winged Foot the year before last, Tiger wouldn't have been sitting so happily in front of his television set. Woods and Mickelson aren't hyphenated, really. Nobody is close enough to Woods even for a long dash. Peter Kostis, Gary McCord and Dave Pelz have managed to convince themselves and most of the public that Phil is the king of the short game. And it is probably true that he is more likely than anyone to hole out from anywhere. But he is also more likely than Els to leave a ball in the bunker and more likely than Tiger to leave a flop shot short of the green. It's possible that Phil is the second-best golfer in the world. It's plain that he's the second-most-popular one in America.

In different corners of Southern California, Phil's dad was a Navy flier, Tiger's pop an Army infantryman. Swinging in the mirror image of their fathers, both tykes started out as left-handed golfers. The first time he was turned around, Tiger repositioned his hands without any prompting. "Tida!" Earl shouted from the garage. "Come out here and look at this!" But Phil wouldn't be turned around by anyone. He always went back to his own way.

Where Palmer took Nicklaus alone under his archangel wing, Tiger fell under a canopy of older players, led by Mark O'Meara, John Cook and Payne Stewart. "Don't worry about your boy," Stewart told Earl on a clubhouse balcony. "I'll watch out for him." Electing Florida for its balmy weather and lack of a state income tax, Tiger homesteaded there in abject loneliness. Alicia O'Meara, Mark's wife, took pity on Woods and brought him into their family. He paid her back by teaching Mark how to win major championships. The Masters and British Open that O'Meara finally won at 41, the 15th, 16th and last victories of his PGA Tour career, ought to be footnoted in Woods' incredible record.

"The reality is," Mickelson said last season, "even if I play at the top of my game for the rest of my career and achieve my goals — let's say, win 50 tournaments and 10 majors [18 and 7 more than he has today], I still won't get to where Tiger is right now. So I won't compare myself with him. It makes no sense." This was the most profound thing said all year in golf. In a way, it set Phil free.

Palmer and Nicklaus didn't have so far to come to end up friends. They had been friends before. Waiting out Woods and Mickelson might take longer. But Player was close enough to Arnold and Jack to know they are both very good men, and there are players close enough to Tiger and Phil to bet that the cold spell won't last forever.