Courses

A Man of The Munys Celebrates The Soul Of American Golf

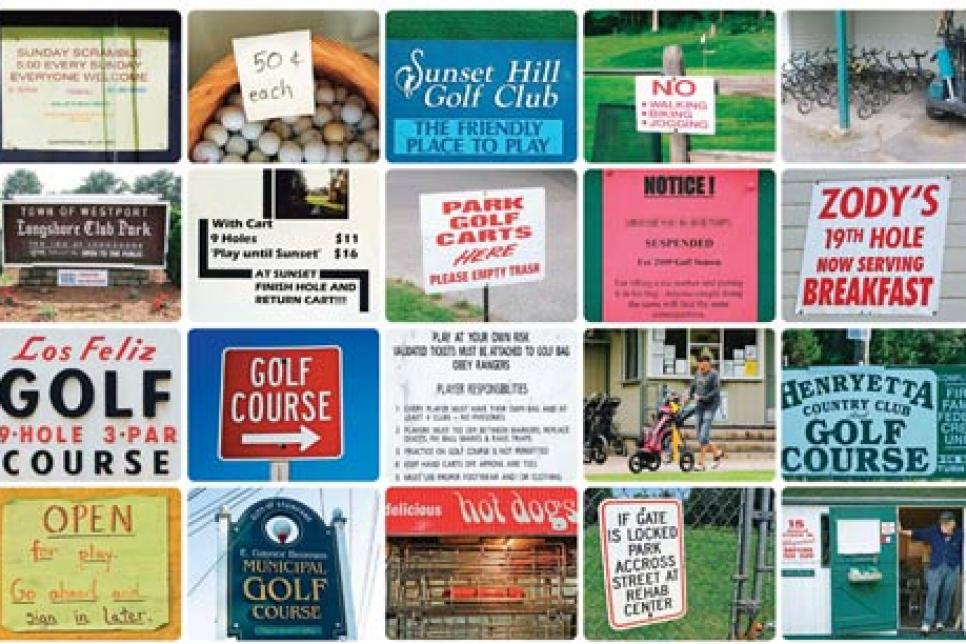

Photos by J.D. Cuban, Dom Furore and Stephen Szurlej

__Editor's Note: Click here to see the 2011-2012 ranking of America's Greatest Public Golf Courses.

__

Nouns are seldom improved by the modifier "public." Few of us, given a private alternative, prefer public restrooms or public transportation or public displays of affection.

But the public golf course is different. Like public television, public golf embraces everything from the exclusionary ("Masterpiece Theatre" and Pebble Beach) to the execrable (pledge week and your local muny).

Consider the very word muny. It comes from municipal, from the Latin munus: "service performed for the community" or "public spectacle, gladiatorial entertainment." And that's precisely what a quintessential public course provides: public service and gladiatorial entertainment.

Gladiatorial entertainment? J.P. Hubbell, while betting a friend in a stroke-play match, drove four consecutive balls off the same house while trying to cut a dogleg at Edinburgh USA in Brooklyn Park, Minn., each ball resonating like a gunshot. When Hubbell struck the house with a fifth ball, the homeowner emerged, waving a white towel.

Public service? Years ago, children helped my brother search for his lost ball at Jackson Park Golf Course in Chicago -- and even offered to sell it back to him on the next tee. That entrepreneurial spirit, on the site of the 1893 World's Fair -- which introduced Cracker Jacks to the United States -- exemplifies America, to say nothing of American public golf.

And so, as jobs disappear and country clubs close and golf comes under serial assault from Congress, it is time to celebrate the democratic, accessible, affordable public golf course. I pledge allegiance to the flagstick ... and tree branch, bunker rake and anything else that has ever substituted for a pin at your favorite place to play.

What could be more e pluribus unum? Like arranged weddings or transcontinental flights, public golf affords a single the chance to spend a very long time in the company of a stranger. And I do mean stranger. Golf Digest Editor-in-Chief Jerry Tarde often played at a Philadelphia muny with an elderly gentleman who put Elmer's Glue on his grips and then shook coffee grounds over them to increase the tackiness. (In every sense of that word.) When Tarde passed him in the parking lot after one round, the guy was on his knees, spray-painting his own Cadillac.

Bill Sullivan grew up playing at Norwich Golf Club, a muny in a blue-collar section of Connecticut. "The course championship was once won by a guy in a 'Lick It, Slam It, Suck It' tank top," recalls Sullivan, with admiration. "He shot two under."

That's something you seldom see at Augusta, the green jacket slipped over a sleeveless T-shirt from a local bar. And more's the pity. Some people dream of playing Augusta National. Give me Augusta Golf Course, the public track nearby. I was there the weekend Tiger Woods won his first Masters, in 1997, and watched the golf-shop attendant answer the phone all day with the greeting: "I think you want Augusta National." He was right: Television viewers were calling in for souvenir scorecards.

But here's what you don't get on Magnolia Lane: Drive up to any public course, and you'll see the world's largest open-air locker room. Golfers -- some in jeans and T-shirts -- are sitting on their back bumpers, putting on their shoes, tailgates flopped open like tongues of panting dogs, salivating in anticipation.

Which is exactly what I was doing when I parachuted into the center of the country to seek the soul of American public golf.

Scarcity drives up demand, and the short golf season in Minnesota makes residents of that state mad for the sport. It's the same reason ancient Scandinavians worshiped the sun: because they saw so little of it.

Every April, the state's pricier public courses advertise pay-the-temperature rates, the green fee being the thermometer reading at check-in. "I know guys who consult The Farmer's Almanac," says Mike McCollow, my friend and fellow Minnesota native. "They tee off when it's 33, hoping it will warm up to 50 by the turn."

Here, public courses really are one part public service, two parts public spectacle. The former Elmdale Hills course in Miesville, Minn., employed llamas as caddies, giving new life to Carl Spackler's line: "Hey, Lama, hey, how about a little something, you know, for the effort?" (This is, after all, the Gopher State.)

In 1991, stockbroker Dennis Olson opened Albion Ridges, 27 holes an hour west of Minneapolis, as an affordable analog to Interlachen, the venerable Twin Cities country club. "I wanted to call this place Outerlachen," says Olson, 72, overlooking his course.

"You always hear about the trouble golf is in," says Olson, in the almost inaudible way of native Minnesotans. "That's because a lot of people have done it the wrong way. They're selling real estate, not golf. Here, beers are two dollars. There's no restaurant. A sandwich, chips and a drink from the fridge case cost five bucks. Those guys over there are playing golf right now." He gestures to the next table in the clubhouse, where men are playing dice golf and drinking two-dollar beer from the can and insulting one another in the tradition of 19th holes everywhere.

A plaque lists the ladies' course champions by year. Olson's wife, JoAnn, seems to win it every other year.

"What happens in the years she doesn't win?" I ask him.

"Someone else shows," he says.

I had just played the course in the kind of gale that is common in Albion Township. ("Albion" is the original name of Great Britain.) The flags are custom-made five inches shorter so as not to blow away, and even then we had a blind approach to the seventh green on the Granite Nine, as the midget flag had been borne away on the wind. The other sticks were almost bent double, the flags flapping like the raincoat tails of a hurricane reporter.

The course is ringed by silos and soybean fields, all visible from the raised Porta-Potties that require the full-bladdered golfer to ascend a small set of stairs before relieving himself. My foursome referred to each one, with admiration, as an "elevated pee box."

On the Boulder Nine, general manager Brooks Ellingson had stopped his cart at No. 6 and warned: "This is where the course toughens up. My buddies and I call the next few holes our Amen Corner."

It was an important reminder: Every public course is someone's private club. After the round, as I headed for the clubhouse -- my hand on my head to keep my hat from blowing off -- I was thinking of Albion as my own quasi-private sanctuary: A-Gusty National.

Apart from a brief country-club membership a decade ago, I have played public courses almost exclusively in my life, though exclusive is perhaps the wrong word when it comes to public golf.

The city I grew up in, Bloomington, Minn., is home to what is probably the most-played course in the state: Dwan Golf Club. Dwan (rhymes with "swan") opened in 1970 on land donated to the city by Dr. Paul Dwan.

"It was originally intended to be a community center," says Rick Sitek, the resident pro and golf manager.

"And, in a way, that's what it has become."

The course is a mile from Minnesota Valley Country Club, where I was once a member. But playing Dwan, I never felt like a man living in his tool shed, within sight of his former mansion, after his wife had thrown him out of the house. On the contrary: Dwan is beautifully maintained and so full of birdsong that it almost sounds piped in.

In winter, the clubhouse stays open for breakfast and lunch, allowing cribbage and bridge players to enjoy the Snack Bar's beloved cheese-and-onion-and-bacon Dwan Burgers year-round. "If I was playing Hazeltine, I'd come here after the round to get a Dwanny Burger," says a guy named Stu, biting into this double-bypass-on-a-bun.

Everyone knows everyone at Dwan. "People treat it very much like their private club, in both the good and bad aspects of that," says Sitek, who has been at Dwan for 20 years. "Some come in without calling for a tee time, and when we tell them there's no room, they say, 'But I always play on this day at this time.' "

And they do. The same people play every week, usually at the same time.

"If I pulled a tee sheet from Wednesday a year ago," Sitek says, "I guarantee you it would be almost identical to today's."

Of the 50,000 rounds played at Dwan last season, only 18,000 of them were played by nonpatrons. On this Wednesday in May, only three tee times go unfilled. The economy has had no effect on Dwan, which is not surprising. The cost of a round -- $21 for patrons, $28 for nonpatrons -- has gone up only six bucks in the last 20 years.

The drought of 1999 is responsible for the longest golf season in Minnesota. Dwan was open 210 days that year and had 62,000 starts. By comparison, the temperate, year-round warhorse that is Rancho Park in Los Angeles might host almost twice that many annual rounds -- and countless more simulated rounds on its two-tier driving range.

Speaking of Rancho, it is a strangely illicit thrill to drive a golf ball from the upper deck of that range in West L.A., making one feel less like a golfer than a member of the Rolling Stones, tossing his TV from a hotel balcony onto Sunset Boulevard circa 1972. But I digress.

In the morning, Dwan skews old: It appears to be hosting the cast of "Cocoon." (Ancient Scandinavians still worship the sun here.) In the afternoon, Dwan skews young: The Jefferson High School girls' jayvee golf team is hosting a match. (When I ask their coach, Tim Carlson, how he remains so fit, he says: "A steady diet of Dwanny Burgers.")

But Dwan seldom skews between. "There is never anyone from age 20 to 30 out here," says Sitek. "It's a whole lost generation. They came out when Tiger first came on the scene. Ten years ago, the course sounded different; you could hear the screaming and cheering from in here. But they found out golf was really hard and never came back."

Still, Dwan is hardly quiet. There's always a train whistle in the distance, and manifold other sonic distractions. My friend Mike McCollow is drawing back his club on approach to 12 when what sounds like an air-raid siren goes off. "First Wednesday of the month?" he asks, 9-iron still raised. "One o'clock?"

Indeed it is 1 p.m. on the first Wednesday of the month, when Minnesota tests its tornado sirens. The siren for central Bloomington is on No. 14, and if you're on that tee when it goes off, your game will never recover.

Such are the challenges of public golf everywhere. Before its renovation into a public jewel, Dyker Beach in Brooklyn had playing hazards that famously included yellow crime tape and burned-out auto bodies. Lt. Col. Earl Woods, while stationed at nearby Fort Hamilton Army Base, learned the game there, which might be why his son is so mentally tough.

Still, Tiger's famous aversion to camera shutters and distant coughing and other backswing distractions would not serve him well at one of the courses in my regular rota, a formerly private club called Tower Ridge in Simsbury, Conn. Tower Ridge shares a border with the state police firing range, and gunshots ring out throughout your round. Instead of No Hunt signs, the placards in the woods along the 13th fairway read Warning -- Firearms In Use -- Keep Out. It's half PGA, half NRA, and I never search for lost balls there. The cops' errant shots trump mine.

Tower Ridge will sell you 10 domestic beers and a cooler pack for 30 bucks, but at least a fraction of the fun of public golf is sneaking beers onto the course. Last summer, my friend Bill Sullivan and I used the large No Coolers sign between the parking lot and golf shop as a screen to smuggle beers onto The Links at Union Vale in LaGrangeville, N.Y. At such times, the cans in my sleeves and pants legs give me the stiff, metallic gait of The Tin Man from "The Wizard of Oz."

But then smuggling contraband beverages onto courses is an art form, one that Sully calls "Ice Cubism."

Speaking of beers: Back at the Dwan clubhouse, a member of my foursome spills an entire pitcher of Michelob Golden Draft on the clubhouse carpeting. I ask Sitek if we'll be getting a letter of reprimand from Dwan regulars, as we might expect at a country club. "Believe it or not, it isn't the first time a pitcher of beer has been spilled here," he says. "Which is why we're replacing the carpet next year."

It's not true that the friendships formed over bacon burgers and beers in Dwan's clubhouse will last until the grave. On the contrary: They last well beyond the grave. Just outside, under a shade tree, are six plaques commemorating six buddies whose regular group was called the Rutabaga Open. When the first of those friends died, the others bought a memorial plaque in his name and mounted it on a rock beneath the tree. When only one of the six remained -- Wy Thorson -- he bought his own plaque. When he died in 2005, Dwan mounted Thorson's plaque next to those of his friends. And what a pleasant place to pass eternity, just behind the ninth green.

Dwan has one of my favorite finishing holes in all of golf. Just behind the 18th tee box is 110th Street, a busy, four-lane thoroughfare bearing -- from a golfer's perspective -- all manner of motorized menace: trucks pumping bass, drive-by hecklers, un-mufflered motorcycles. "There used to be a family across the street whose kid rode this crotch rocket," says Sitek. "He'd do wheelies up and down the street all day."

Otherwise, there is a happy detente between Dwan and its neighbors. The course, owned by the City of Bloomington, replaces the windows of homeowners for free. Garage windows get Plexiglas. From the 14th fairway, I could see eight balls on the other side of the chain-link fence, which rises as high as 18 feet for one stretch. They were all bunched next to one another, a little unhatchable bird's nest three feet from a shed whose windows appeared to be Plexiglas.

A sign on the course reminds golfers: There Are Young Children In The Area -- Please Refrain From Abusive Language. As a result, much of the swearing here is done sotto voce, in the manner of a cat burglar who stubs his toe in the dark.

But mostly it's just friends idling away the day. On this Wednesday, a group of retirees stands on the elevated 18th tee box. The first gentleman hits a utility wood, and the ball goes almost straight up, a remarkable achievement for a club with only 16 degrees of loft. The man immediately scrambles down the hill to fish his ball from a creek that runs in front of the tee box. In a nearby pond, an aerating fountain shoots a geyser of water in the air, as if the Earth is doing a spit-take.

After retrieving his ball from the water, the gentleman stands fully upright -- and is abruptly forced to hit the deck as one of his oblivious playing partners tees off behind him.

While watching this tableau from the 17th green, I am reminded of Thomas Chalmers. He was born where modern golf was, in Scotland in 1780, so it's no surprise that the mathematician and minister is best remembered for this utterance: "The public! The public! How many fools does it require to make the public!"

Answer: Usually, just four.

ALL-STARS OF PUBLIC GOLF

__Tiger Woods:__Developed his skills at California public tracks: Heartwell Par 3 and Recreation Park in Long Beach and Dad Miller in Anaheim.

Lee Trevino: A local legend in the money games at Dallas' Tenison Park.

__Tom Bendelow:__The Johnny Appleseed of golf-course architecture designed dozens of public courses in 30 states, including the first, New York's Van Cortlandt Park.

Joe Jemsek: Chicagoland patriarch of public golf, the owner of Cog Hill and two other facilities was the first public-course owner on the USGA Executive Committee.

Alfred (Tup) Holmes: Led an effort to end the segregation of Atlanta's public courses in 1953 with a lawsuit that was upheld by the Supreme Court. An Atlanta course now bears his name.

__Nancy Lopez:__Learned the game on a nine-hole muny and another city course, New Mexico Military Institute Golf Course, in Roswell.

Calvin Peete: Introduced to golf at Genesee Valley Park in Rochester, N.Y., in his 20s.

__Moe Norman:__Canadian pro played often at the city-owned Rockway Golf Course in Kitchener, Ontario, sometimes 72 holes a day.

Fred Couples: Grew up riding his bike to Seattle's Jefferson Park with his clubs.

Hale Irwin: First played on the sand-greens muny in Baxter Springs, Kan.

Ken Venturi: A regular at San Francisco's Harding Park and Lincoln Park as a junior.

Dr. David Bronner: Led the development of the largest public golf project in history, Alabama's 11-site Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail.