Courses

Members Mostly

See how the other half lives at opulent Manor Golf & Country Club.

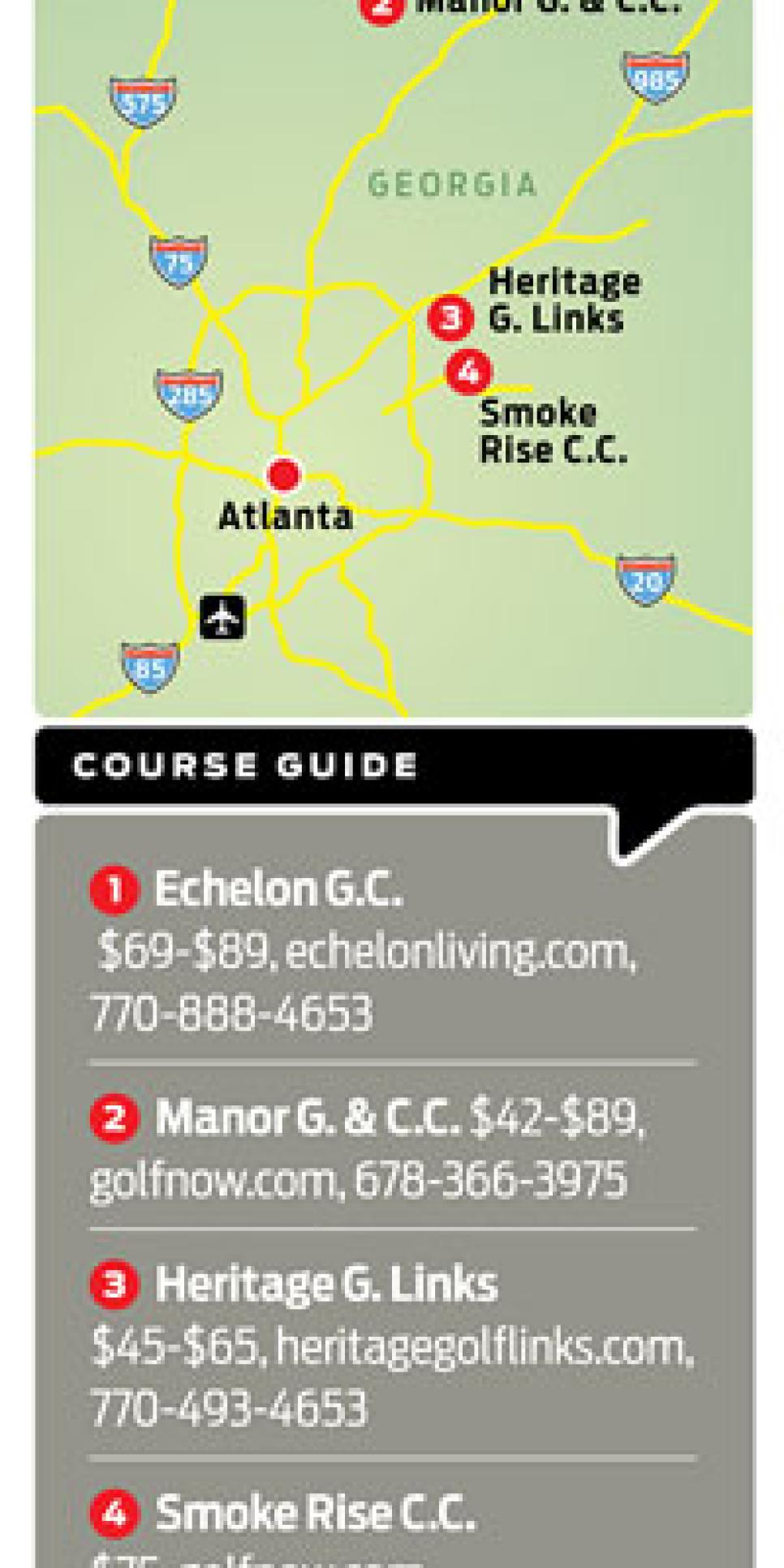

I took the early flight from New York and was on the first tee of Heritage Golf Links at 10 a.m. The course is northeast of the airport, but you can avoid downtown traffic by momentarily heading south to loop around on I-285. In the great sprawling beast called Atlanta, there's always another way.

Built in 1996, Heritage is most famous because Dr. J owned it. Hall of Fame slam-dunk pioneer and unaccredited physician Julius Erving bought the 27-hole complex in 2006 and renamed it Celebrity Golf Club International. Dr. J imagined his private club would cater to retired athletes and stars flying in now and again--an Augusta National with laxer clubhouse rules--but the grand opening coincided with the market downturn of 2008. Not enough people joined, and Dr. J lost the course in foreclosure in 2010. I called ahead, gave no name, and was told to come on by.

Standing on the first tee, there's no need to consider economic sourness. The staff is happy to have you, and you're getting to play an ambitious, well-kept layout for a bargain. The grass range has three tiers, and the one at the top marked "members only" is the smallest.

The starter paired me with a potbellied, retired importer/exporter from Paris who dressed like Dustin Johnson and cursed like Pepe Le Pew. Serge, short for Sergio, is a member, and his guest was a good ol' boy who cast the club like a fly rod at his finish. I moved up a set of tees to enjoy a front-row seat to their colorful bickering over mulligans and gimmes. Along the way we picked up two more singles like barnacles, and finished as a flotilla of five golfers in four carts. No one knew each other. There were no post-round drinks or locker-room shoeshines, but the quality of the golf felt private.

Heritage is a high-end daily-fee course that had a private stint before reverting to its old name and ways, but nearby Smoke Rise Country Club is allowing outside play for the first time since it opened in 1998. Though it doesn't broadcast it, the club has started selling tee times on golfnow .com as an "exclusive, limited opportunity." On the phone I was told to "come on down" but was nearly denied at the golf shop when I couldn't produce my member number. Glancing over his shoulder as if to verify the coast was clear, the pro said I could go off the back if I could play fast, then charged my credit card $59. Pressing my luck, I asked if I could walk but was gruffly told no because of the high Slope Rating of 145.

Slope Rating, of course, is a measure of scoring difficulty, not hilliness. But it's true that courses like Smoke Rise aren't set up to walk. Many courses struggling financially are similar in that few were conceived to be self-sufficient. Manicured holes with massive features routed through deep acreage are costly to maintain, but if homes are sold as part of a gated community, the cost is offset. When enough homes sell, that is.

Whitney Crouse of Affiniti Golf, a management company that works to turn distressed courses profitable, explains: "If a store goes out of business, the next owner of the building can use it for apartments or another type of store. Golf courses can't be repurposed. Too much has been invested to bulldoze them."

This is why you and I can play stunning layouts like Smoke Rise for green fees that don't equal the true value of the experience. No use crying about how these courses should've been built more modestly. The golf's there, so we might as well play it.

Manor Golf & Country Club started allowing limited daily-fee tee times just last year. The guard at the palatial security gate won't let you through without a tee time, but you can book one at golfnow.com. The stone terracing of a few tee boxes rivals Roman proportions, and with as many as five wrought-iron balconies, each home along the Tom Watson-designed course could be mistaken for the clubhouse. As for the actual clubhouse, daily-fee interlopers may appreciate only the exterior. If you want a drink after your round, you're limited to the bar that doubles as the halfway house.

Echelon Golf Club is in horse country an hour north of downtown but worth the drive. Built by Rees Jones in 2006, it used to be called the Georgia Tech Club. Several dramatically elevated tee boxes vie for the most stirring view of the Appalachian foothills. The giant embankments cornering the doglegs are dwarfing, but when you flush a sidehill shot from one, you feel, if just for a moment, like a tiny superman. The tips can play 7,558 yards, and it seems every available penny is funneled to the course. There's no clubhouse, the grill outside the golf-shop trailer might have a burger on it, but the greens are kept as pure as any country club's.

What does the future hold for these "private" clubs? Crouse is cautiously optimistic. "A management company brings in a lot of expertise a private owner wouldn't--like how to manage the food and beverage, marketing, and agronomy like a business," he says. "But long term I think we'll see more courses shifting to the bottom of the market where green fees are more affordable."

It's only an ill wind depending on where you're standing.