News

A Champion's Last Hurrah

All but retired by '67, Hogan still struck the ball with an authority that awed fellow pros.

As was his custom, Ben Hogan arrived early for the 1967 Masters, more than a week before he would suffuse the emerald stage with uncommon drama. It had been years since Hogan was a favorite -- Jack Nicklaus would be shooting for his third straight green jacket -- but he was still Hogan, not quite a man in full but full of intrigue. He came with his flat linen caps and his cigarettes, his shoes with their extra spike, a suitcase full of gray and a golf bag clanking with the extra-stiff-shafted clubs he still commanded like a drill sergeant barking to a hapless private.

"It's hard to remember specifics of playing with Hogan because he always hit it perfectly," says Deane Beman, who was paired with him in the first round at Augusta National GC that week. "He hit almost every fairway, put it right where he wanted to. He played to the middle of the greens and always left himself uphill putts. He seldom hit a shot that short-sided himself. There wasn't anything remarkable about the way he played, except he played remarkably."

Hogan was a bit thicker through the middle than the Hawk of peak flight, the gritty bantam who ruled the sport in the late 1940s and early '50s, his slightly relaxed waistline befitting a 54-year-old man who spent as much time behind a desk as on a golf course. Having subsisted on oranges when he was a poor young golfer hooking his way to nowhere, the graying icon liked to lunch on fruit plates to try and drop a few pounds in preparation for Augusta's sharp hills, slopes that could wear out a younger man, much less someone north of 50 with suspect wheels.

He tuned up for the Masters, as he had forever, at Seminole GC in North Palm Beach, but this spring training wasn't as vigorous owing to a bothersome left shoulder, one of the residuals from the horrific 1949 car crash that nearly killed him. "An indication of the Hogan sharpness for the 1967 Masters is given by his suntan," reporter Jim Martin observed in a pre-tournament story for The Augusta Chronicle. "It isn't as deep as last year."

In fact Hogan's shoulder, plagued with bursitis, scar tissue and calcium deposits, had nearly kept him away from the major championship he had won in 1951 and 1953. "I developed some trouble last year, and it [hurt] all year," Hogan told reporters in Augusta. "So I decided it needed some work. But I got two shots of cortisone two consecutive mornings and have had 15 shots since then that helped it."

The injections—more of them than a doctor likely would allow today—lessened the inflammation and quieted the pain. Hogan knew another surgery would be necessary, but the scalpel could wait. He had competed in every Masters but two ('49 because of the crash and '63 after a shoulder operation) since his first appearance in 1938. Bobby Jones wanted him in Augusta, and Hogan wanted to be there. The Masters was golf, and Hogan was a golfer.

Hogan was the antithesis of tournament-tough when he got to Georgia, his last competition being the 1966 U.S. Open at Olympic Club where, playing on a special exemption from the USGA, he finished 12th. But inactivity didn't equal rust for Hogan. "He hits the irons so good, he's cheating," one of his protégés, Gardner Dickinson, told the Chronicle after a Sunday practice round. "He hits it three feet from the hole at No. 6 and the pin was right on top of Old Smokey [the right knoll]."

The distinctive sound of Hogan's crisp shotmaking had become part of golf lore, but Bruce Devlin judged him with another of his senses. "He had the best control of the elevation of the ball of anybody that I ever played with," says Devlin, who as a young pro in the 1960s traveled with fellow pro George Knudson to Fort Worth to watch Hogan hit balls and was Hogan's frequent practice-round partner in his last tour appearances. Standing behind the legend as he hit drivers, Devlin would hold up his fingers, like a Hollywood director envisioning a scene, and see ball after ball soar through the same frame. "He had fantastic control. They all looked the same when they went off the club—no real low ones, no real high ones."

A cadre of pros usually took advantage of a rare Hogan sighting on tour to watch him practice—the range was far from "Misery Hill," as World War II-era pros called it, to Hogan—but average golfers craved a look, too. On Tuesday morning at Augusta in '67, Clem Darracott, a 41-year-old freight-line salesman from Atlanta who had attended the Masters for several years, approached Hogan as he exited the clubhouse heading for the practice tee and asked if he could film his swing with an eight-millimeter home-movie camera.

Photo: GD Resource Center

As detailed by Curt Sampson in Hogan, the Hawk wasn't a fan of movie cameras in his prime, likening their buzzing sounds to those of rattlesnakes that frightened him so as a boy. Hogan rebuffed CBS' attempt to capture extensive images of his swing at Augusta one year, but had allowed LPGA legend Mickey Wright to shoot eight-millimeter movies of him in 1965.

"I had watched Hogan so much [at the Masters] that I had the feeling he was aware I had been a fan of his," recalls Darracott. "They had publicized it in the Atlanta papers that it would be the last time he would play [the Masters]. I think that was one of the reasons he allowed me to film. He thought, 'This guy's a fan. He's got a home-movie camera. I'll probably never see him again. Why not?' "

Hogan invited Darracott onto the range. From the side and down the line, he filmed Hogan as he worked through his bag while his jumpsuited caddie shagged the balls in the distance. Hogan's setup is without tension; on many swings his shoulders rotate beneath a lit cigarette. The action is dynamic and fluid, differing from his younger swing only in how he moved through impact—with a bit less stress on a more relaxed left side. "In those days it was a battle with those knees of his," says Devlin, "particularly the left knee. He just couldn't drive up onto his left side the way he used to, yet he found a way to make it work."

Later, Hogan welcomed Darracott to follow his practice round: Hogan and Devlin played against Jay Hebert and Jackie Burke Jr. "I understood it to be $100 a hole," Darracott remembers, "and Hogan was taking their money right and left. He hit so many shots up close to the hole you couldn't believe it."

Darracott got a sense of Hogan's precise expectations on the 17th hole, where he watched the group's approach shots land on the green. "He walked over and asked me where his ball hit," Darracott says. "[I told him], and he grunted and said, 'It should have hit three feet back here.' "

New bunkers in the landing areas at Nos. 2 and 18 were a hot topic before the tournament. Some players were grousing about them, but not Hogan, who dismissed the added hazards with characteristic bluntness. "I don't care where they put the bunkers," he said. "You shouldn't be in the bunkers or the woods." Similarly, he refused to join the chorus of complainers about the fairways, whose rye overseed was causing some jumpy lies. Said Hogan, "I see nothing wrong with the course at all."

But the no-fuss, no-excuses, no-doubt-it-was-going-to-be-a-good-swing legend turned mortal once he walked on a green. "My putting impediment" was Hogan's description. It didn't happen on every putt, but when it did, it was ugly—as if a fine, purring engine suddenly coughed and refused to turn over. Especially in contrast to his still-graceful long game, Hogan's putting often was a jerky, messy, labored ordeal that didn't seem like it could belong to golf royalty. "Once I put the putter back of the ball," he explained, "sometimes I can move and sometimes I can't."

Once one of the game's surest putters, Hogan never knew when the paralyzing tentativeness would crop up. Dan Yates, an 88-year-old Augusta National member who has been to every Masters tournament, remembers one moment of an older Hogan. "I never will forget watching him on No. 11, standing over about a three-foot putt," Yates says. "I timed it—it was a couple of minutes before he could draw the putter back."

During the 1966 U.S. Open Hogan locked up over a putt so severely he walked away toward fellow competitor Ken Venturi. "He was looking at me without seeing me. He said, 'I can't draw it back,' " Venturi recalls. "I said, 'Who gives a damn? You've beaten people long enough.' And his eyes opened and he damn near made [the putt]."

As he teed off in his 25th Masters, Hogan knew he could connect with the dime-sized sweet spot in his Hogan irons until Augusta's azaleas lost their blossoms and bloomed anew, and he would still be battling his putter. Nothing in his first two rounds certainly changed his mind. He opened with 74-73, workmanlike scores by a hard-working man, good for T-23, seven strokes behind leader Bert Yancey.

Photo: Courtesy of Augusta National

Hogan fared much better than Nicklaus, who blew to a second-round 79 to miss the cut by one shot (one of only two times he didn't play the final 36 holes at the Masters from 1960-1993). Nicklaus stuck around for the weekend to award the green jacket to the winner, and after sleeping in Saturday, he went to the course and watched some golf on a cart with club co-founder Clifford Roberts. The gallery acknowledged Nicklaus' presence on the second nine with applause, but it would make more noise for someone else.

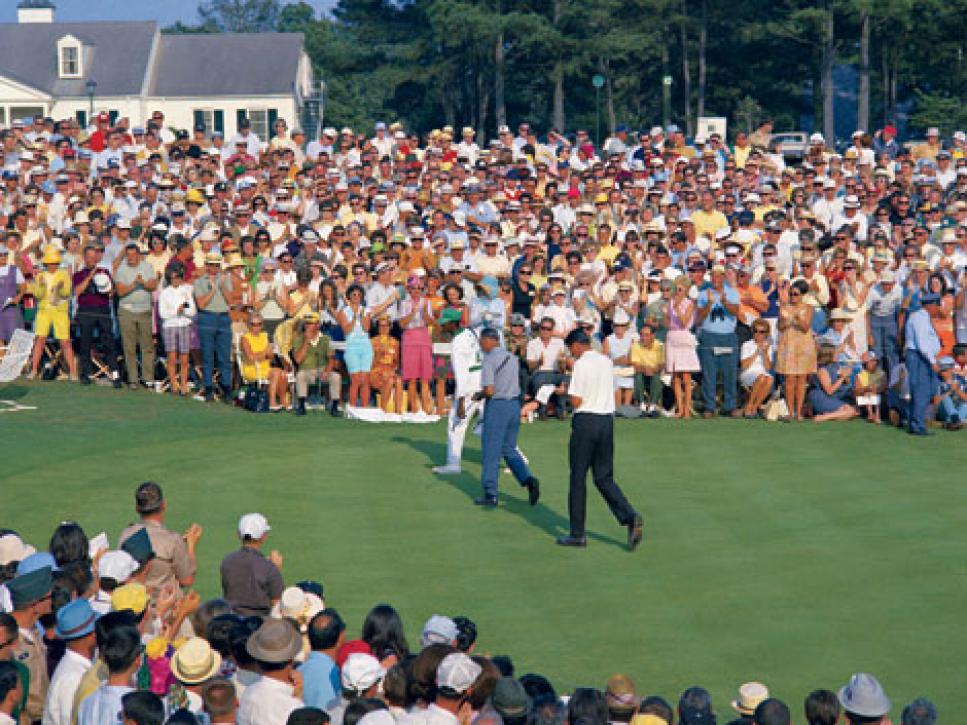

The third round was played on a good Coppertone day, the temperature reaching 77 degrees. The larger world was busting open over war and race in the 1960s, but golf spectators generally minded their manners, didn't hoot and holler. "In those days," says Venturi, "there was no yelling and screaming, there was just applause." Fans simply put their hands together, louder for some players than others, rising to their feet if the moment called for it, and the afternoon on April 8, 1967, was one of those times.

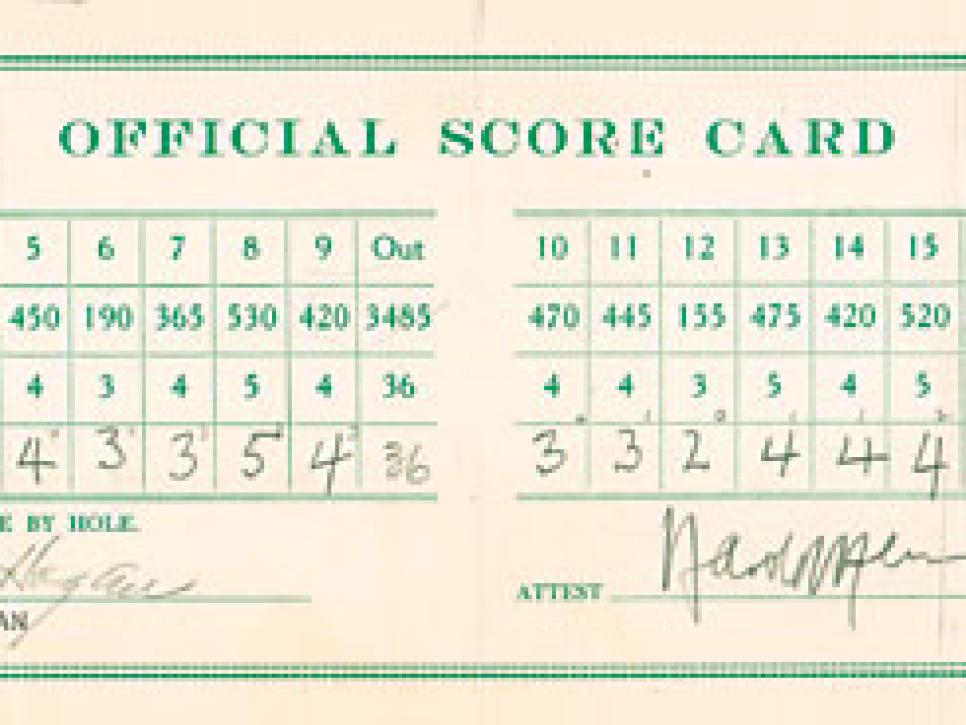

Hogan, "the little champion of another era," as the Associated Press called him, teed off at 12:24 p.m. with 32-year-old Harold Henning, one of the golfing Henning brothers from South Africa. The first nine was as low key as the first 36 holes, Hogan turning in even-par 36 after escaping with a 5 on the par-5 eighth, where missed 18-inch putts had led to double bogeys Thursday and Friday.

Taking the bit of better karma with him toward Amen Corner, Hogan began to peel away the years. A strong drive at the 10th set up a 7-iron to seven feet. Birdie. Another good tee shot on No. 11 left him with a 6-iron that he drew to a foot. Birdie. He chose the 6-iron again on the par-3 12th, hitting it to 12 feet. Birdie.

"I putted better than I have in a long time," he said later that day. "I'm still embarrassed to get before people in a tournament and pretty embarrassed on a putting green alone. The only way I can beat the thing is to play in a tournament. But I conquered it out there today."

Often Hogan liked to pitch-and-putt his way to success on Augusta's par 5s, but on the 13th a 4-wood approach left him within 15 feet, where he two-putted for his fourth straight birdie. "What happens with someone like that, your body goes back in time," says Venturi. "He was no longer that [54-year-old] person. He was back in the early 1950s playing golf. He was in a zone."

Frank Chirkinian was directing a CBS broadcast that was being done with substitutes calling the action because the talent and the technicians were on strike. "I had all the management guys on towers as announcers," says Chirkinian. "One of our guys identified Tommy Aaron as 'Tommy Walker, a member of the Aaron Cup team.' "

Hogan was subjected to no misidentifications. A par at the 14th was followed by another two-putt birdie at No. 15 after another pure 4-wood second shot. As he strung the shots together, orderly as the laundry of a neatnik housewife, Hogan remained his implacable self on the outside. "I remember Dad saying [Hogan] never acknowledged anything that he said to him," says Hanley Henning, whose father died in 2004. "Every time he hit a good shot and Dad acknowledged it with 'Nice shot,' he never uttered a word. Not a thank you."

In Hogan's immediate wake, in the 12:32 pairing, were Doug Sanders and Chi Chi Rodriguez, Technicolor counterparts to the taciturn Hawk, with a trailing view they still remember. "If you weren't playing with Ben Hogan, it was a privilege to play in front of or behind him because you could watch the whole thing," says Rodriguez. "Hogan was such an icon," says Sanders. "Just to be in his presence and breathe the same air was very unusual because you didn't see him that much."

There were standing ovations at every green, and necks craned to see Hogan's name on the leader boards. "Naturally the atmosphere was charged," says Dan Jenkins, a longtime Hogan chronicler who was covering the Masters for Sports Illustrated. "Chirkinian claims he was crying in the truck when Ben came up the 18th fairway. I believe it. A lot of us teared up. But we didn't let [crusty Pittsburgh writer Bob] Drum see us."

Chirkinian's cameras caught Hogan on No. 18, wearily making his way to the elevated green. "He was really struggling to get up the hill," says Chirkinian. "They were slow and deliberate steps, and it wasn't because he was looking for applause, I'll tell you that." Hogan vowed after three-putting No. 18 to lose the 1946 Masters to Herman Keiser that he never would leave his approach above the hole, but he had, 25 feet away. Still he sank the putt to come home in 30 for a 66, and trail 54-hole tri-leaders Yancey, Julius Boros and Bobby Nichols by two shots.

"Usually, when a long tournament day is over, the galleries plod for the exits tired in eye and limb, but there were no weary steps that evening," Herbert Warren Wind wrote in The New Yorker a couple of weeks later. "Hogan sent us home as exhilarated as schoolboys."

The protagonist wasn't feeling too bad himself. "I saw him upstairs after the round," says Venturi. "He wasn't one to jump around, but you could see the twinkle in his eyes and the satisfaction he had. He said, 'That's not something I dreamed I could do.' "

Addressing reporters, Hogan sounded like the realist he had always been. "As for chances of winning," he said, "a lot of fellows are going to have to fall dead for me to win. But I'll tell you one thing: I'll be playing as hard as I ever have in my life." His wife, Valerie, told The New York Times on Sunday she would "consider it a miracle if Ben won."

Says Jenkins: "I knew 66 would be his last hurrah. I remember Drum and I putting his over-under number on the final round at 75."

Hogan began his final round with a par, but the euphoria of the previous day evaporated quickly with bogeys on the second, third and fourth holes. He was wary of all the tight hole locations and three-putted four times en route to a 77 that dropped him to T-10, 10 strokes behind Gay Brewer Jr., who closed with a 67 to edge Nichols by a stroke.

The gallery masked its disappointment, standing and clapping at every green, appreciation for the body of work and the man. "What a phenomenal day it was," says Joe Black, who was on the rules committee. "In the last round Ben got a standing ovation on every hole. It was almost chilling." Hogan visited the pressroom Quonset hut for the second-straight day for an interview. "You fellows must be gluttons for punishment," he told the reporters, "asking me to come down here and describe my round. Jeepers, creepers, it was awful."

He would not return to the Masters, not even to attend the Champions dinner he helped start in 1952. He continued to make rare tournament appearances until 1971, when his bad knee forced him to make an ignominious withdrawal from an event in Houston.

Everyone had a Hogan story, but he owned the memories.

"You talk about something running up and down your spine," Hogan told Furman Bisher in The Masters in 1976, recalling that special Saturday in '67. "I'd felt those things before. I'd had standing ovations before. But not nine holes in a row. It's hard to control your emotions. I think I played the best golf of my life on those last nine holes. I don't think I came close to missing a shot."

In 1995 Clem Darracott's movie of Hogan was marketed as a video, 23 minutes of a maestro tuning up for his last virtuoso performance. After receiving a copy, Valerie Hogan invited Darracott to Fort Worth. She told him "it was the first time Mr. Hogan had seen himself swing."

Until his death at 69, Harold Henning liked to look at a framed newspaper clipping that had a prominent spot in the den of his Miami Beach home. It hangs there still, the front page of the April 9, 1967, Augusta Chronicle-Herald. The focus of the page is a four-column photo of Henning standing over the man who wouldn't talk to him, helping him check his scorecard, signing off on a day that really wasn't about numbers at all.