News

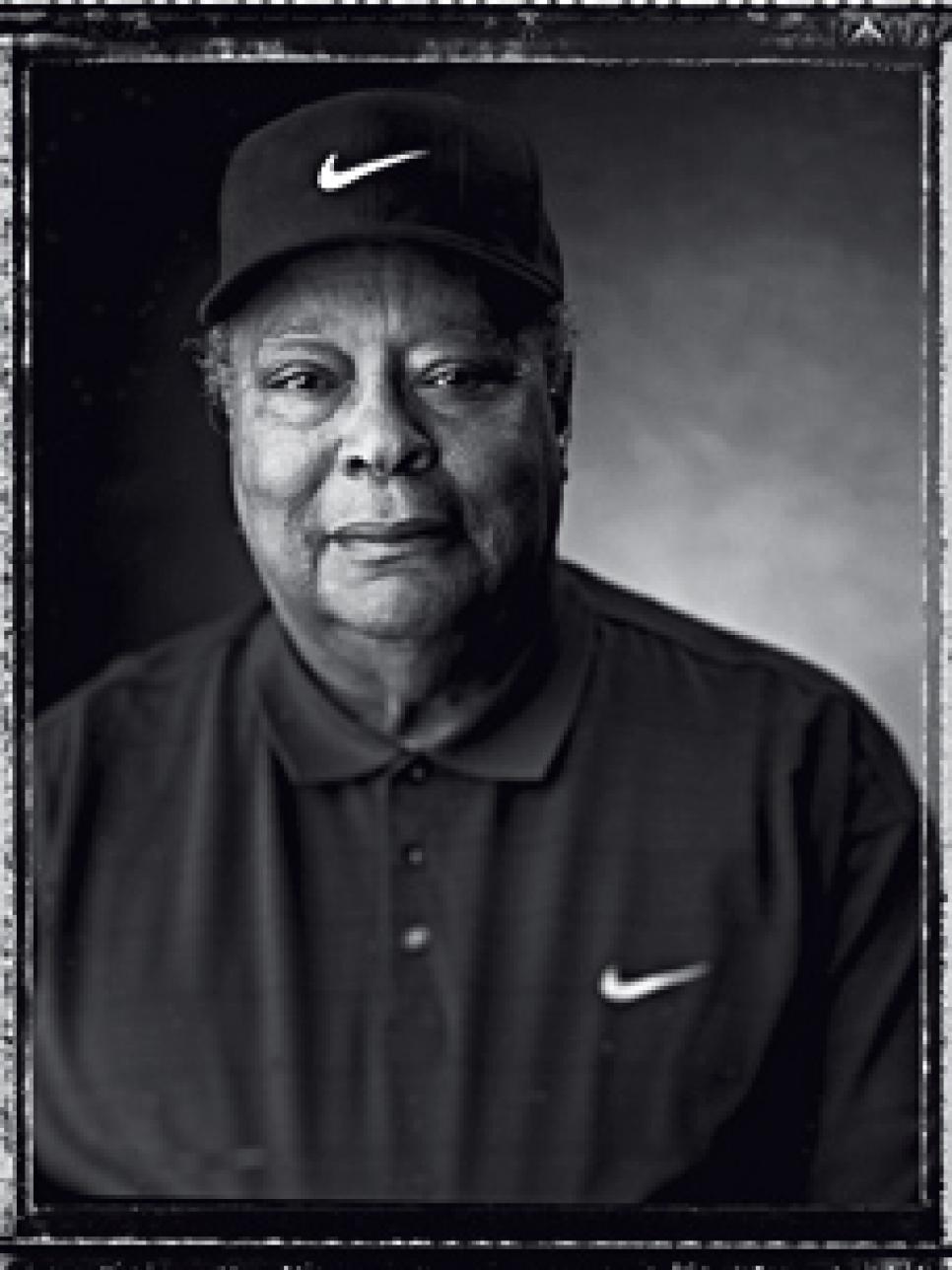

The Genius of Earl Woods

Father knows best: Earl's observations often seemed like hyperbole until Tiger proved him right.

The facts sometimes sounded like boasts, but Earl Woods, as the world would find out, knew his son better than anyone else. After all, he had been there from the beginning, the very early beginning. After seeing Tiger, not yet a year old, solidly strike his first golf shot, in a scene recounted in Tiger by John Strege, Earl ran from his makeshift garage driving range inside the house and shouted to his wife, Kultida, "We have a genius on our hands."

From a distance, many people misjudged the man who, in concert with his wife, mentored and molded the talent displayed that day by the diapered Tiger. Earl Woods wasn't a tyrannical parent who pushed his child into doing something he didn't want to do. As writer Peter de Jonge noted in 1995, Earl's parenting style "is more Mr. Rogers than Great Santini … the two have the kind of unambivalent, unharried relationship more common between a grandfather and a grandson."

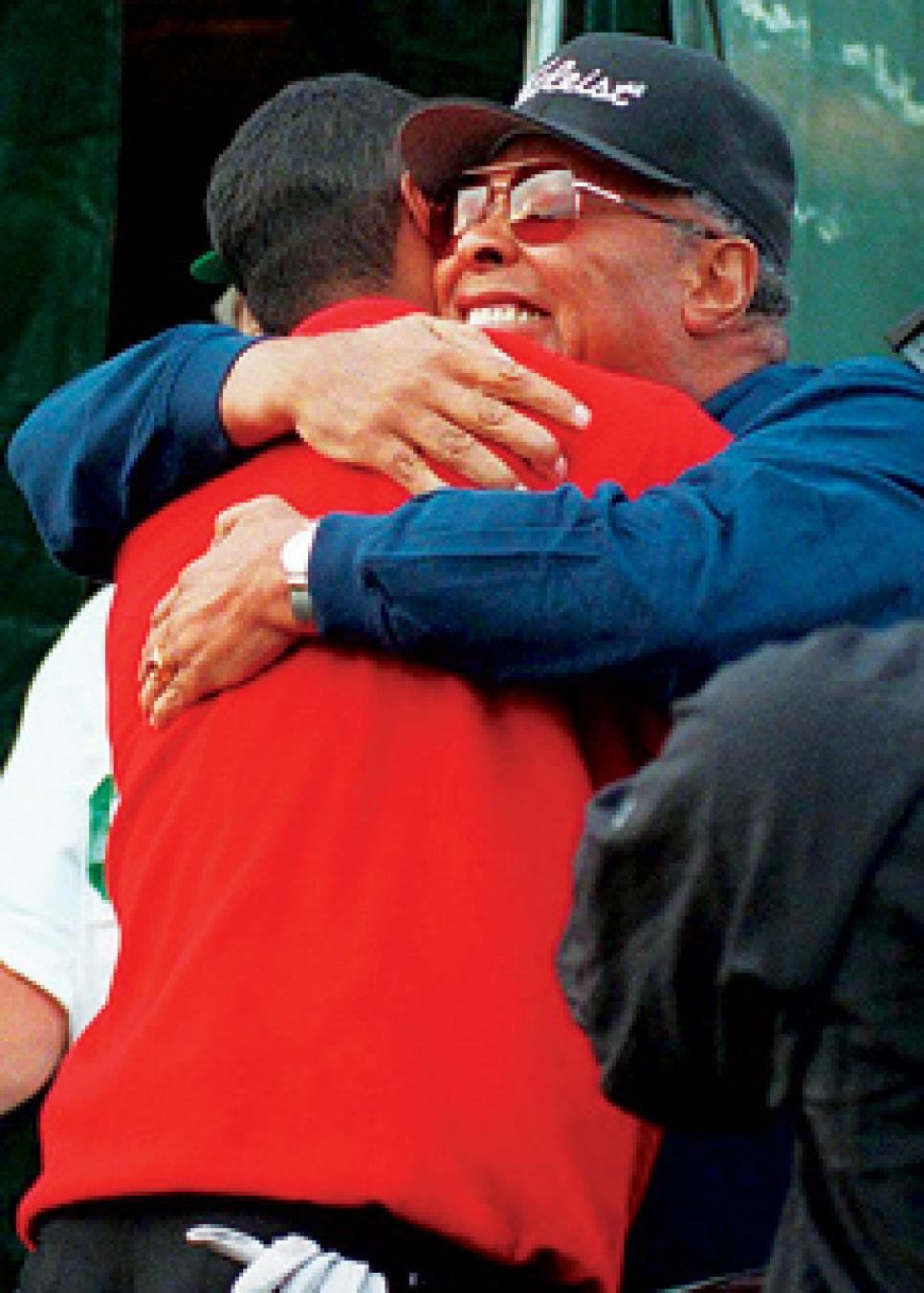

Earl Woods, 74, who had been beleaguered with heart problems and diabetes and battled cancer since 1998, died May 3 at his home in Cypress, Calif. The public first became aware of the seriousness of Woods' condition at the 2005 Masters, when Tiger became emotional at the jacket ceremony. "This one is for Dad," a tearful Tiger said. "Every time I've won this tournament my dad's been there to give me a hug, and he wasn't there today. I can't wait to get home and see him and give him a big bear hug."

Later, explaining his emotions following his fourth Masters win, Tiger said: "He's hanging in there, and that's why it meant so much for me to be able to win this tournament. Maybe give him a little hope, a little more fire to keep fighting. I never cry in public, but I couldn't help myself. I didn't know what was happening, but it just shows what he means to me, the place he holds in my life."

Tiger Woods, who had curtailed his playing schedule at times this season to be with his father, said last week on his website: "My dad was my best friend and greatest role model, and I will miss him deeply. I'm overwhelmed when I think of all the things he accomplished in his life. He was an amazing dad, coach, mentor, soldier, husband and friend. I wouldn't be where I am today without him, and I'm honored to continue his legacy of sharing and caring."

Fathers have influenced many of golf's stars, whether by their absence or their presence. Chester Hogan killed himself when Ben was a boy. Robert Tyre Jones and Charles Nicklaus were strong figures in the lives of their sons, Bobby and Jack. No golf father, though, gained a higher profile than Earl Woods, who was in a second marriage and 43 years old when Tiger was born in 1975.

Tiger's birth name was Eldrick Woods, but it was Earl who began calling him Tiger to honor a South Vietnamese soldier named Vuong Dang (Tiger) Phong, who had fought beside Earl, and saved his life, during two tours in Vietnam as a Green Beret. The nickname was the perfect moniker for a child who craved competition and a man who eventually dominated his sport.

Earl Woods grew up in Manhattan, Kan., the youngest of six children whose parents died before he was 13. He excelled as a baseball catcher and earned an athletic scholarship to Kansas State. The first minority athlete in the Big Seven (now the Big 12), Woods was offered a contract by the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League after his freshman year. His father wanted him to be a professional baseball player, but his mother had stressed the importance of getting an education. Woods stayed in college, took ROTC and graduated with a sociology degree in 1953.

He had three children (Earl Jr., Kevin and Royce) with his first wife, Barbara, but absences caused by his military duty hurt the marriage and his relationship with his children. "I would change things," Woods told Golf Digest in 2001. "Tiger is the only one I've been able to spend his entire life with. The rest of them have big holes--I'm gone a year and a half, I'm gone six months. I tried to repair it when they were between 18 and 21 … A lot of the damage had already been done."

Taking advantage of a fresh start with Kultida, Woods immersed himself in Tiger's life. Having just taken up golf the year before and quickly becoming proficient at it, he was eager to expose his fourth child to the game. He did that when Tiger was only a couple of months old--Tiger would sit in his high chair in the garage while Earl hit balls into a net. "I was lucky," Earl wrote in Training A Tiger. "Tiger took to the game immediately. Much like me, he had an instant infatuation with it. And I always kept him wanting more." Accentuating the positive while steeling him later with the realities of being a minority sportsman, Earl fed Tiger's hunger for golf but didn't demand it. "The saddest thing in competitive athletics," Earl told Golf Digest, "is to see an athlete competing because he or she is required to compete, not because they desire to compete." John Anselmo, one of Tiger's early golf instructors, told Newsweek in 1996, "so far as I know Earl never pushed Tiger to do anything."

"The best thing about those practices was that my father always kept it fun," Tiger wrote in an introduction to Training A Tiger. "It is amazing how much you can learn when you truly enjoy doing something. Golf for me has always been a labor of love and pleasure."

When Earl attended Tiger's tournaments during his teens, he often camped out a fairway over, sitting on his folding chair listening to jazz on a Walkman, puffing on an omnipresent Merit 100. When Tiger was 14, he called his father, "the coolest guy I know." The "Saturday Night Live" skit in which a Tiger Woods character remarked about having a golf club glued to his hands was far from the truth.

Jack Nicklaus, also 30 when his dad died, said last week: "My father was my best friend, my mentor and perhaps my greatest support system. Earl was all of that to Tiger."

Yet Earl also was a man who jingled keys and coins during Tiger's backswing to increase his ability to concentrate, and who read him the riot act on his 13th birthday when Tiger behaved badly and didn't give his all in a junior tournament. A couple of days went by before Tiger told his father: "Pop, I heard every word you said. I promise I'll never quit again." Tiger's doggedness became as much a part of his repetoire as his spectacular shotmaking. "That is the beauty of Tiger," Earl told Golf World's Ron Sirak in 2000. "He never mails it in. He always gives the best that he has that day. I taught him that you don't lose because somebody else beats you; you lose because somebody else had a better day."

Despite his son's precociousness, Earl encouraged him to dominate one level before moving on to the next--but the father always had a sense of what lay ahead. "Before he's through," Earl told Sports Illustrated in an unguarded moment in 1995 after Tiger's second U.S. Amateur victory, "my son will win 14 major championships." Tiger, who turned 30 last December, has 10 professional major titles, and 13 overall including his three U.S. Amateur victories.

Earl Woods had quadruple bypass heart surgery in the 1980s, but had a hard time giving up smoking or fatty foods. At 64, he suffered a heart attack during the 1996 Tour Championship. When Tiger won his historic Masters title in 1997, Earl sat by the practice green and watched part of the final round on a television monitor before going to the 18th green to hug his son after he won. Woods was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1998. The cancer returned in 2004, when he revealed he had lesions on his back and a tumor behind his left eye.

His illness soon limited his travel and work as president of the Tiger Woods Foundation, the golfer's charitable concern, and the man who inspired his son to contribute to life beyond the golf course was unable to attend the opening of the Tiger Woods Learning Center in February. But Earl Woods remained a part of his son's golf life. "I'll tell him what I'm going to do on every hole, and we run through it together, just like we always do," Tiger said on the eve of the 2005 U.S. Open final round, which was played on Father's Day. "That's special, man."

Earl Woods took pride in letting go as his son got older, and he knew that given his age when he fathered Tiger, he wouldn't be able to see all his feats. "Obviously, I will not be here to see the final result," he told GQ magazine in 1997. "I will see enough to know that I've done a good job."