News

Demaret: A Great Showman

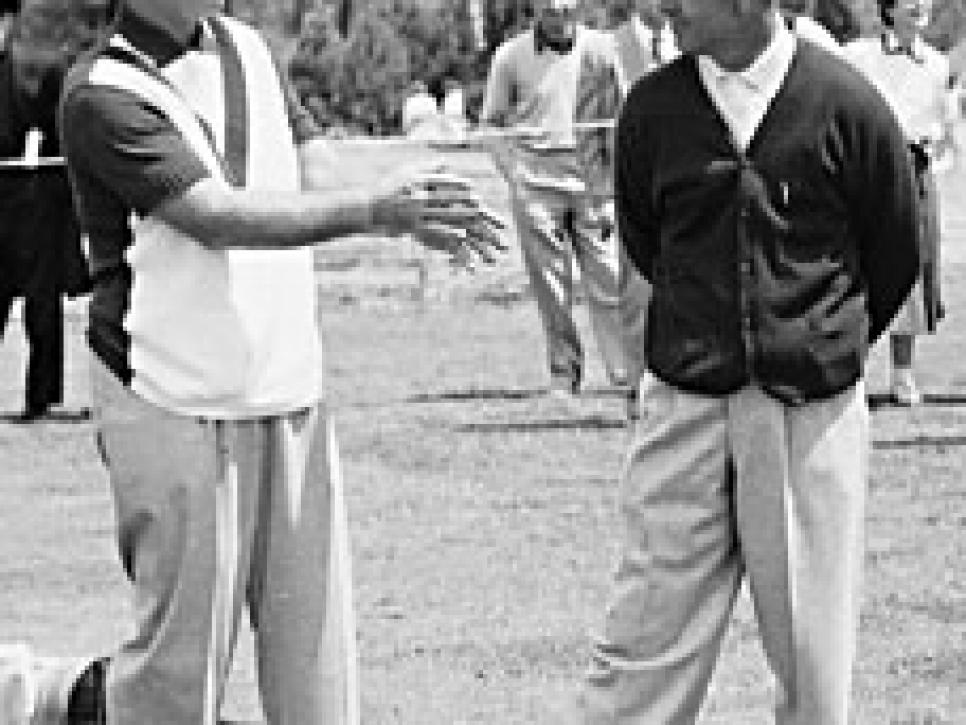

Demaret (left) jokes with Lloyd Mangrum while winning his first Masters in 1940

There is more talent than you can count in professional golf these days, but not so many characters. This is a reflection of the times as much as the people. With the corporations crowding in and the money stacking up, there is less gin and more juice, more stock quotes and fewer memorable quotes. Golfers do their curls in a fitness trailer, are in bed before Letterman, and never have to wonder what their swings look like because of the video camera they tote with them, along with the multivitamins, magnets and laptop computer. If he were coming along now, the forces would conspire against Jimmy Demaret being who he was, but no doubt he would make it a good fight, taken late into the night with a big smile, a cold drink and likely, if he were in the mood, a song.

"Get out and live," he said once. "You're dead for an awful long time."

By all accounts, Demaret took his own advice. Although 2000 is the 90th anniversary of Demaret's birth and marks 50 years since he became the first man to win the Masters tournament three times, those who knew him well don't need to be prompted by the calendar to remember. Talk to someone about Demaret--someone who heard the jokes, was warmed by the grin or saw him shimmy into his narrow stance and create a best-selling fiction of a shot that did a fox trot upon landing--and the joy seems as fresh as today's paper.

Demaret, who died of a heart attack in 1983 when he was 73, wasn't the game's first showman and he won't be the last--in so much as the species can exist at all in these perfect turf, exact yardage, courtesy-car times--but the multi-talented Texan carved a singular niche. "He was a wonderful guy, a happy-go-lucky devil," says Sam Snead. "I never met one person who said they didn't like Jimmy Demaret."

He made his mark by combining a winning game with a congenial personality that bulged with generosity and humor. He was a nightclub-quality singer, at ease and not needing many shots when he was alongside Bing Crosby, as he often was. And he was smart, despite having had to drop out of school before he got to junior high to help his disabled father support a family of nine children. "Many people don't know how unbelievably bright he was," says Jack Burke Jr., Demaret's longtime friend and business partner at Champions GC in Houston, which the pair built in the late 1950s. "He had a mind like a Swiss watch, a tremendous mind. He became a pilot, and he could handle boats with big engines. He had a great memory. I don't think people know how complicated he was."

From 1938 through 1957--a lengthy span of success few golfers have achieved--Demaret won 31 PGA Tour events, tied for 13th place in career victories. Runner-up in the 1948 U.S. Open, he finished one stroke out of the playoff in the national championship in 1957 when he was 47 years old. At 51, in the 1962 Masters, he finished fifth. And when he was 53, he nearly became the oldest-ever winner of a tour event, losing a playoff to 28-year-old Tommy Jacobs at the 1964 Palm Springs Classic.

"Tommy's a good boy and it was nice he could win," Demaret deadpanned afterward. "After all, I've got a lot of years left, and he's about through." Demaret had more wins than Lee Trevino, Johnny Miller or Gary Player, despite the fact that from 1951 forward he played the tour part-time while spending much of each year tending to his duties as a club pro. Demaret's prime was also interrupted by World War II, which he spent in the Navy stationed at Corpus Christi, Texas, playing not an insignificant amount of golf.

"Every war has a slogan," Demaret said. " 'Remember the Alamo,' or 'Remember Pearl Harbor.' Mine was, 'That'll play, admiral.' "

Demaret struck the ball low so it wouldn't be affected by the wind ("You could hang laundry on the 1-irons he hit," says a friend, Bernie Riviere), but no one was unaffected upon meeting Demaret. That long list would include Bob Hope, who borrowed jokes, and Ben Hogan, who learned shots from him. "He was the most underrated golfer in history," Hogan said. "This man played shots I haven't even dreamed of. I learned them. But it was Jimmy who showed them to me first." In the khaki and gray days during and following World War II, Demaret was an Easter parade of color in custom-tailored clothes that could brighten Juneau in January. "Everybody looked like pallbearers," he observed of the monochromatic circuit he joined. "I learned early that color puts life into things." Demaret got a sense of color from watching his father, John, a painter and handyman, mix paints. In time, he married the red-haired Idella Adams, and he turned into a rainbow. "Just before he would step on the first tee," recalls the Demarets' only child, Peggy, "everybody in the gallery would say, 'I wonder what he's going to have on today?' "

Demaret might pair a dusty rose cardigan with an electric blue shirt and green suede shoes. Or he could choose garments of flaming scarlet, peach, purple, tangerine, burgundy, canary yellow or vermillion topped with a showy tam crocheted by his mother-in-law, Ethel. It was a 64-Crayola collection that set a vivid standard for peacocks such as Doug Sanders and Payne Stewart who followed him. Snead remembers arriving at a hotel in South America once with Demaret to play some exhibitions, and as soon as his friend got out of the car, necks craned and traffic stopped. "When he got out of that car," Snead says, "it was like everybody stopped breathing." He was paying for clothes what people were putting down on a house: In 1954, he counted 71 pairs of slacks, 55 shirts, 39 sportcoats and 20 sweaters. Over the years he accumulated hundreds of pairs of shoes, most with a brightly covered saddle, and when he got older, he'd let friends go up in his attic and pick out a pair to take home. Decades before Forrest Fezler slipped on a pair of shorts during the 1974 U.S. Open, Demaret defied authority and bared his legs during a hot tournament in Chicago.

While people noticed what he wore, they remembered what he said. In an era when most pros worried much more about keeping their shag bag full of golf balls than filling reporters' notebooks, Demaret was full of witty observations, one-liners usually, that often had him laughing before he finished his delivery. "He could put people down without being mean, and he told jokes on himself," says former tour pro Bob Goalby. "He acted like he knew you even if he didn't. He made you feel good about yourself."

A gas siphon hose was an "Oklahoma credit card." Lew Worsham, the 1947 U.S. Open champion who had a prominent chin, was "the only guy in the world with a built-in bib." When Sam Snead started putting with a side-saddle style, Demaret said, "He looks like he's basting a turkey." At the Crosby one year, everyone awoke Sunday morning--some after less sleep than others--to see Pebble Beach coated with snow. "I know I got loaded last night, but how did I wind up in Squaw Valley?" Demaret said. Of Bob Hope, Demaret quipped, "He has a wonderful short game. Unfortunately it's off the tee."

Demaret's humor could pop up at any time, prompted by almost anything. "He had the freshest, sharpest wit," says Riviere. "He could respond to any situation with something funny, and it was always his—he didn't steal material from anybody. We always felt if he kidded you, he liked you." Riviere, his brother, Jay, and Dave Marr--a trio Demaret had taken under his wing--headed out on the 1959 winter tour without much success. "The Crosby was about the fourth tournament of the year and Jimmy shows up," Riviere says. "He said, 'I wasn't coming out this early but I was worried about you. I thought you might have been killed.' "

Johnny Bulla remembers one Masters in the early 1950s when Frank Stranahan, the buff amateur, showed up after an off-season of working on a swing that looked much different than it used to. Demaret, waiting to tee off at the first hole, peeped, "I thought Hogan was the one who had the accident." Johnny Carson was a foil for Demaret on an appearance on "The Tonight Show" in the 1960s. Carson swung a club and asked Demaret what he thought. Demaret, shifting positions to get a different view, asked him to swing again. And again. "Tell you what, John," he finally said. "If I were you, I'd lay off for a couple of weeks." Demaret paused--Cary Middlecoff at the top of his backswing--and told Carson, "And then I'd quit."

Demaret came from grinding poverty, a family of nine children that often wondered how their plates were going to get filled. Some of the children lived for periods in other homes so life wouldn't be so hard. "We were a very poor family," says the youngest of the Demaret children, Mahlon, who was 13 years younger than Jimmy. "He had quit school and was caddieing and shining shoes by the time I came along." The circumstance of his youth, according to his daughter, forged his outlook later. "If you struggle hard when you're growing up," says Peggy Jackson, "never knowing where you'll get your next meal, you treasure the things you have."

By the time he was 16, Demaret was working as an assistant pro to Jack Burke Sr. at the exclusive River Oaks CC in Houston. Occasionally, Demaret would babysit the young Jackie Burke, who was 3 when Demaret started at River Oaks, but he spent most his time sanding wooden shafts, building clubs and then polishing clubheads when they rusted. The labor strengthened Demaret's large hands and inflated his forearms, giving him a blacksmith's power.

A few years later, he became a pro at the municipal course in Galveston, hard by the Gulf of Mexico, where an ever-present wind punished shots that weren't spanked underneath it. Demaret honed a left-to-right game that would become the envy of his peers. Owing to his four-year apprenticeship on the shore, most of Demaret's shots were low, solid darts with a slight fade--no one, it is widely thought, has ever been better in a breeze. If his windcheaters needed to bounce or check quickly, he could make it happen.

"He had a simple move," says Burke. "He knew where the face of the club was at all times. The club broke [cocked] the same way every time. He didn't really have to practice." The taciturn Hogan loved being around the locquacious Demaret, but may have gotten his most pleasure from watching Demaret strike shots when they teamed in the Inverness Four-Ball in Toledo, Ohio. Hogan noticed how well Demaret's bread-and-butter fade stayed in play and made the style his own, scaling the heights once he did so. "Ben copied Jimmy's game," Burke says bluntly. "Jimmy was a left-to-right player, and Hogan didn't carve a career for himself until he started moving the ball left to right."

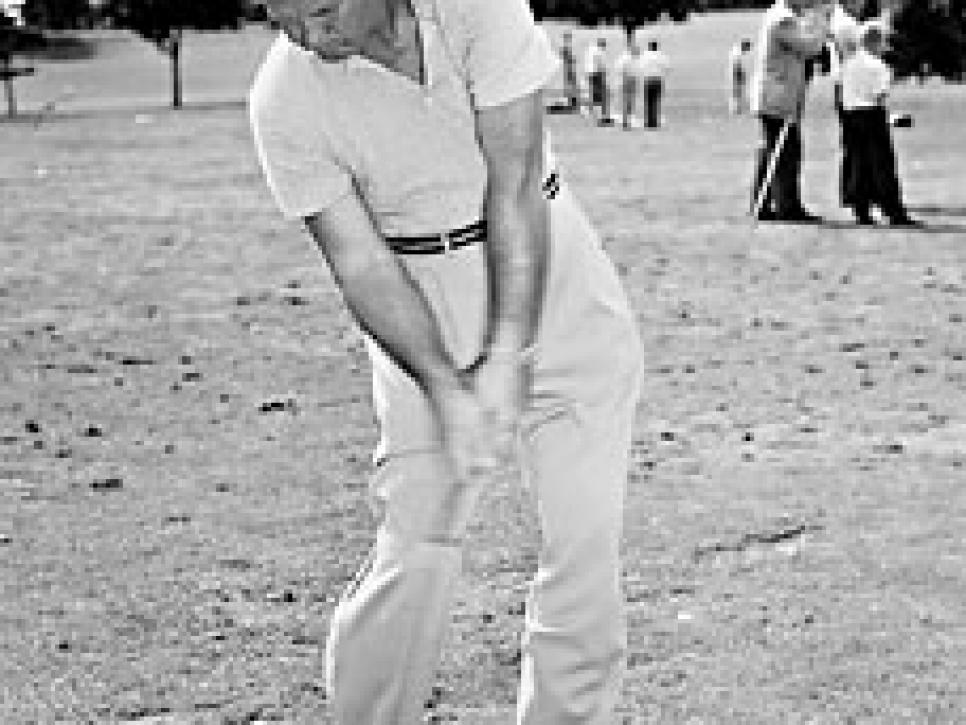

Demaret, stocky at 5-feet-10 and about 200 pounds, had the build of an offensive guard from the days when boys got strong working on the farm. "Nobody was stronger than Demaret," Burke says. But his sturdy buttocks, thighs and calves carried him along lightly. As historian Al Barkow described in Golf's Golden Grind, Demaret "had technique and mannerisms that were the stuff of pantomime. He walked with a short, quick, rhythmic step, like someone treading over a fairway of unbroken eggs, his buttocks shimmying from side to side."

A majorette would have been proud of the way Demaret twirled the club as he approached his ball. Even as he settled into his narrow stance, everything was in motion, fluid movements of someone who knew how to keep a beat. To keep his golf muscles supple, Demaret often swung a weighted club. Demaret's balance was extraordinary. A foursome of golfers at Champions once found out just how good it was one day in the early 1960s.

Crowing to Demaret about how well they had played, the men presently found themselves back out on the course in a match against him, four against one. There was a twist. For the first four holes, Demaret played every shot standing only on his left leg. He played the next four holes standing on his right leg. When they reached the ninth tee, Demart was even par and the men were hundreds of dollars down. At that point, Demaret's mercy matched the fun he was having. He gave them enough shots and presses on the last hole so their wallets didn't blow away.

Another time, when Demaret was in his early 50s, he got to the eighth hole of the Cypress Creek course at Champions in a friendly match with some members. The hole was playing about 140 yards, all carry over a lake. "I hit an 8-iron to about 10 feet," recalls Joe Scardino, "then Jimmy hits a 7-iron inside of that. Another fellow in the group--people at Champions will know who he is--said, 'Gee, Jimmy, you won the Masters three times and you had to hit more club than Joe.' " Now, Demaret could run to daylight better than Gale Sayers, and he saw his opening. He took the putter out of his bag, and a bet was made that he could hit the green with the 13 remaining clubs, $100 riding on each shot. Demaret went to work—hooding a sand wedge, feathering a 3-iron, bunting a driver--and was successful every time. "Unbelieveable," says Scardino. "It was the most amazing thing."

Like Walter Hagen before him, Demaret cultivated the image that grew out of the laughs and the late nights. "Jimmy let people think he partied all the time," Al Besselink, who shared some of those evenings with him, observed one time. In a 1956 interview Demaret addressed his lifestyle. "You can't drink--that is all the time, be an alcoholic--and do anything," Demaret said.

"Certainly not golf. I'm a social drinker. I love people. Now, I'll be honest with you. I've overindulged some of the time. And stayed up too late. Probably cost me a few tournaments. I'm sure it has. But I'm not quite the rounder some people may think I am." From his seat, Demaret didn't believe he was in the 100-proof league of comedian Phil Harris, of whom he once said, "Phil Harris can drink more than Dean Martin with one lip tied behind his back."

When Demaret joined Snead to partner with him one year in the World Cup, Snead was worried that his nocturnal pace would affect their results. "That Jimmy, he wanted to go here, there, everywhere," Snead says. "He'd knock on your door at Augusta at 2 a.m. and say, 'Let's go have one.' But that World Cup, I told him I wanted him in bed by 10:30 every night. I didn't care if he was sleeping, as long as he was in his room. By God, he went to bed, played level par and we won by a bunch."

Burke, who spent more time around Demaret than anyone, says, "He never was stumbling around. He probably had a little too much every day, but it never did impair him." The truth was Demaret craved the company around him more than the drink in his hand. "He'd talk about going away somewhere where there was no phone or television," his daughter says. "He might go for two days, then he was ready to shoot himself--he had to come back to civilization."

There is the question of how much better a golf record Demaret might have achieved had he worked harder and socialized less, but there is no consensus. Snead says, "I think he would have won more had he tended to business, but that's just the way he was."

"I think he would have done things the same way," says his daughter.

"His career meant nothing to him," says Burke. "He enjoyed the people in it--the other things were a little bit boring to him."

Demaret was an easy touch for anyone who needed a few dollars. "The dollar didn't really mean a lot to Jimmy," says Burke. "He was extremely generous. He was quick to the draw at a beer joint, would pick up everybody's bar tab. The only time Jimmy balked is when he and I had to buy a piece of equipment for the club or something. When you started talking about $10,000 for the tractor, he'd stutter a little bit."

Because he was so generous, when he died those who didn't know him well wondered about his financial health, but they need not have been concerned. He was a "secret saver," according to one friend, who steered clear of risky ventures. One of Burke's children, Mike, became Demaret's financial advisor in the late 1970s. He was fresh out of the University of Houston at a brokerage in Austin, Texas, where he was supposed to be selling tax-free municipal bonds but for the moment was making coffee and washing the cars of his superiors. One day, Demaret called. "I told him I was making coffee," says Burke, "and he said, 'As soon as you figure out what you're selling, I'll take $100,000 worth."

In the aftermath of Demaret's substantial order, Burke's coffee-making and car-washing days came to a quick end. Demaret continued to do business with him, always insistent that his young friend do first-rate research first. One Christmas, Burke gave Demaret a small pair of scissors so he could clip his coupons. "Ahh, I like to just bite 'em off," Demaret said.

By the time Demaret died, purses were going up and laughs were going away. Looking back on his career shortly before his death in 1983, Demaret wrote, "There was a lot more camaraderie then. We had more fun. The new players are shooting for so much money their eyes are pinched in like BBs. The numbers are eating them up."

Demaret paid attention to a different kind of numbers. At Champions, they still play fivesomes regularly. It is an ode of sorts to Demaret, who liked the bigger group. The extra man afforded more games and more bets, but most important, for the sunniest of golfers, more laughs.