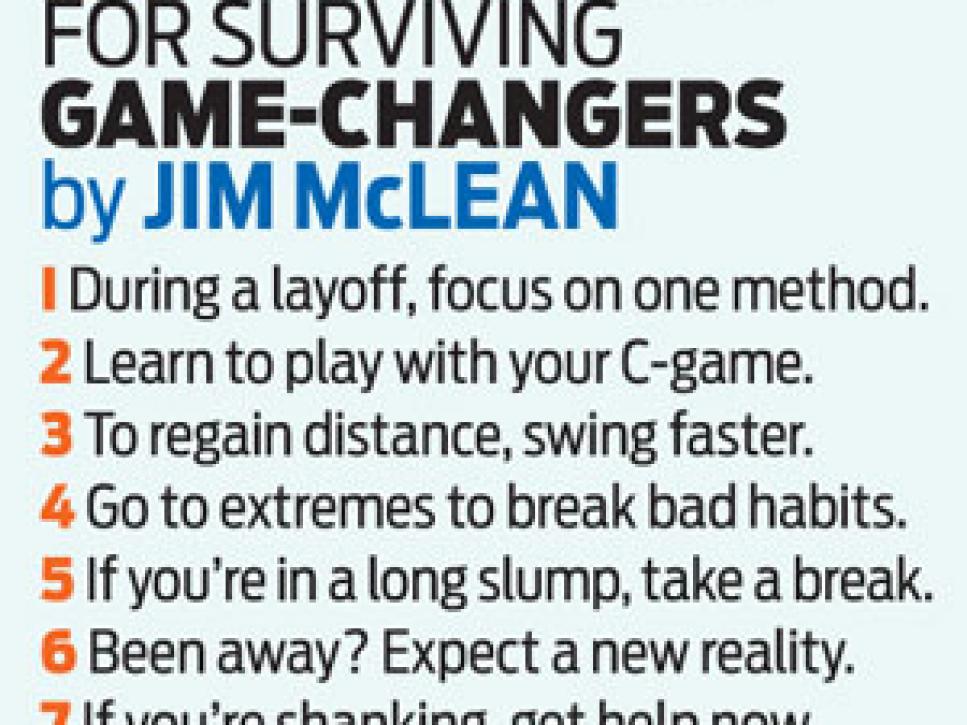

Surviving Winter Breaks, Slumps & Other Game-Changers

'Sam Snead would solve a slump by going home and fishing every day.'

1. During a layoff, focus on one method.

A seasonal layoff can be very useful. Phil Mickelson and Tiger Woods have talked a lot about it giving them time to reflect, recharge their batteries and contemplate a game plan for the upcoming year. My advice is to focus on one type of instruction, and don't fall prey to every swing tip you see or hear. Commit to one concept. If the simple "swing the clubhead" message of Ernest Jones resonates with you, don't mix it with a complicated mechanics-based philosophy. You'll be surprised at how readily the swing you focused on and dreamed about becomes integrated into your game.

2. Learn to play with your C-game.

On the range before the final round of the 2007 WGC event at Doral, Tiger was hitting it all over the place. He was leading the tournament, but he hadn't hit the ball well the day before. There was a look of frustration on his face, but no panic. During his pre-round warm-up, Tiger hit all kinds of shots -- high fades, low punches, you name it -- presumably looking for something that would get him through the day. Suddenly he deliberately hit a sweeping 40-yard hook that turned toward one of the range flags. Then he hit another just like it, and another. That's how he played that day, hitting a huge draw on almost every shot.

Tiger didn't have his A-game, but the 73 he shot was good enough to win by two. On days when your feel isn't good or you just don't have it, find an "out" shot that will get you around. You might not shoot a great score, but you'll survive the day.

3. To regain distance, swing faster.

The late Gardner Dickinson, a terrific tour player in the 1950s and '60s who happened to have a slight build, once asked Ben Hogan what he could do to get longer off the tee. Hogan told Dickinson to stop at the range after every round and hit 30 drivers as hard as he could. He told him not to care where the shots went, but to try to hit the ball on the center of the clubface.

Hogan emphasized to Dickinson the importance of sheer swing speed. Thirty drives might be a lot for you; 15 might do. But a little violence in the swing is healthy and will help you develop more power. You'll never hit it far without ripping it.

4. Go to extremes to break bad habits.

Toward the end of 1991, Tom Kite went into a deep slump with his chipping. Tom's hands were too far forward through impact, which leaned the shaft toward the target and exposed the sharp leading edge of the clubface. Kite hit a lot of chips fat, which in turn had him pulling up to avoid hitting behind the ball. No amount of practice helped.

During the off-season, Tom eventually went to what I call the "contrarian theory," which takes the cure to an extreme. Kite didn't just stop trying to lean the shaft forward, he did the opposite: He tried to deliver the clubhead very early, so his hands were even with the ball at impact. To learn this move, he practiced chipping balls on a practice green, where hitting the ball fat meant tearing up the putting surface. Instead of hitting down on the ball, he tried to clip it cleanly off the turf. Tom got his chipping game back and had an incredible year in 1992, including a victory in the U.S. Open at Pebble Beach.

5. If you're in a long slump, take a break.

If your handicap has shot up several strokes and you're confused, obsessed with mechanics, and have more tension than confidence, then you're in a true slump. Sad to say, it's time to put the clubs away for a while. Sam Snead would solve a slump by going home and fishing every day, even during the middle of the season.

When Hal Sutton went into a slump in the early '90s that took him from one of the best players in the world to almost losing his tour card, he stopped playing altogether and went to Houston to see Jackie Burke, winner of two majors, a superb teacher and the best amateur sport psychologist in golf. The game has a way of beating people up, and Jackie lifted Hal's confidence by reminding him how gifted he really was. Burke reorganized Hal's thinking about his game, and Hal came back to win a bunch of tournaments, including the Players Championship in 2000.

You might not have a Jackie Burke on call, but you can still use the time to appraise your game objectively and identify what you're doing wrong. From that reflection will come some fresh ideas for what you need to do to get back on track.

6. Been away? Expect a new reality.

In the early days of what used to be known as the Senior PGA Tour, many players who hadn't been active in their 40s came out of retirement. A few never got their games back. Others, like Billy Casper and Jim Colbert, reinvented their games and had great success. Everyday players who loved golf early in life but had to leave the game to raise a family or focus on a career tend to think they'll pick up where they left off. But it doesn't work that way. They quickly find everything has changed: equipment, courses and most of all, themselves. Physically and mentally these players aren't as strong, supple or athletic.

Two keys, which I saw in Billy and Jim, will guarantee a smooth return. The first is humility, learning to play around your limitations and becoming a better course manager. The second is concentrating on your game from 40 yards and in. There's no reason you can't pitch, chip and putt as well as you ever have and compensate for the shortcomings of your long game.

7. If you're shanking, get help now. The shank is the worst of all shots because of the instant and indelible imprint it leaves on your psyche. The fear of doing it again is so great that many golfers can't diagnose the problem. My advice: Don't even try to figure it out on your own; see a teacher right away.

When I was the head pro at Sleepy Hollow Country Club in New York in the early '90s, I had a member who started shanking almost every shot. He'd get a basket of balls, go to the range, shank the whole basket and go home. I'd never seen a golfer so discouraged. After some badgering, he let me give him lessons. I did six sessions with him, starting around the greens.

There are four ways to shank. His was a nasty over-the-top loop with an open clubface. I told him to keep his elbows attached to his rib cage from start to finish, so his arms couldn't drift from his body far enough for the hosel to reach the ball. He did this on every swing, and it cured his shanks.

8. Beat age with a weighted club.

The secret to Vijay Singh continuing to play awesome through his mid-40s can be found at his home in Florida. Placed strategically around his property are 10 weighted clubs, which Vijay is always picking up and swinging. Making 20 to 30 swings a day keeps his hands and forearms strong and his back and shoulders as toned as those of a 20-year-old.

Weighted clubs have been around forever, but in an era when clubs are increasingly being made lighter and everybody talks about clubhead speed, weighted clubs and old-fashioned strength have kind of gone away. A weighted club is the best practice device invented. Just remember to swing it slowly and to make your motion as close to the real thing as possible.

9. You can play around injuries.

It's rare to have an injury so severe that you can't play fairly well despite it. Take the case of the left thumb, which is viewed as the linchpin of the grip and is a common source of tendinitis. No less than three players have won the Masters without placing the left thumb on the handle. Gene Sarazen, Claude Harmon and Henry Picard all positioned the left thumb off the right side of the handle, so the right palm did not ride on top of it. So what's commonly thought of as a debilitating thumb injury can be accommodated overnight with a simple grip change.

If you've got a bad back, try swinging more upright with less body rotation. Bad left knee? Play the ball back in your stance, and stay on your right side. There are few legitimate reasons for not playing to a decent level because of an injury.

10. Check your eyes to fix your putting.

Much more common than the yips is the old-fashioned slump where you mysteriously stop holing those tough five-footers that can make or break a round. Your stroke might be fine, but you suddenly start burning edges. It's a devastating thing to have happen, because you start viewing yourself as a poor putt-er, and a bad attitude can make it come true.

If you've stopped converting the "must make" putts, it's probably because of a subtle change in your eye alignment. At address, check that (a) your eyes are parallel to the target line, and (b) your eyes are either directly over the ball or slightly inside the line of play. You'll see the line better and aim the putterface squarely, and your putts will start dropping again.