News

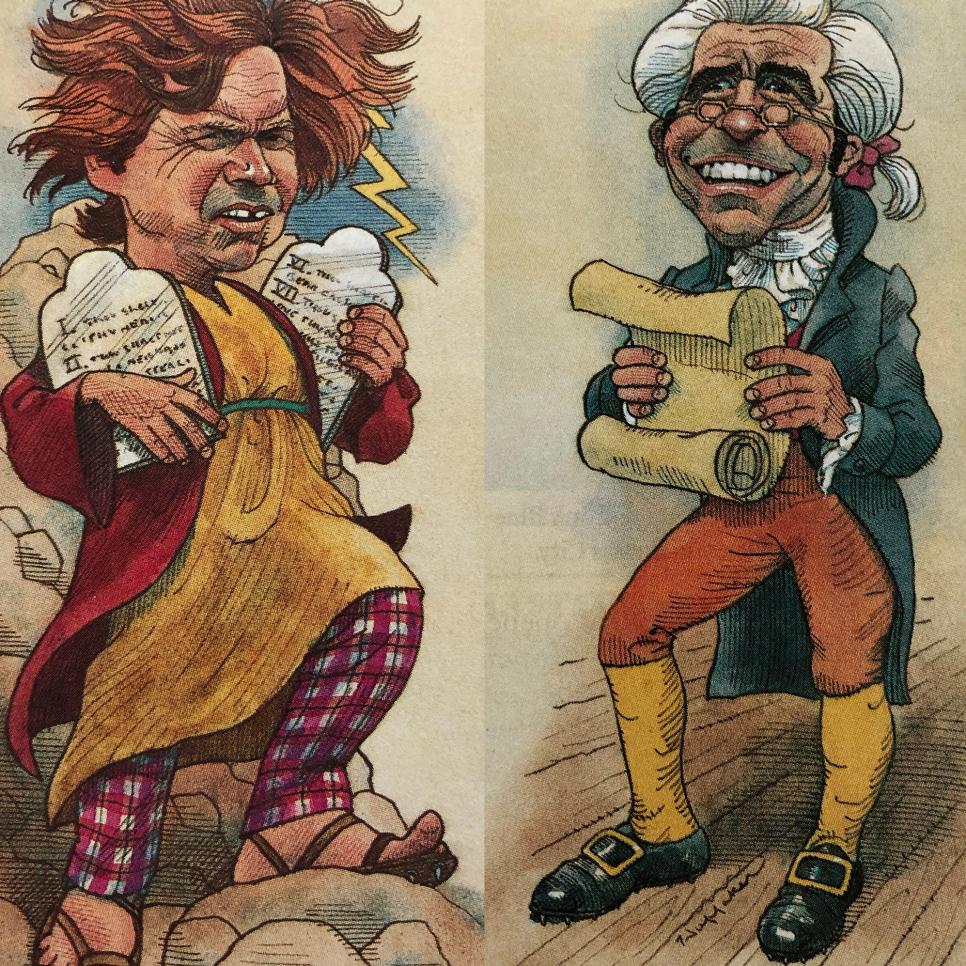

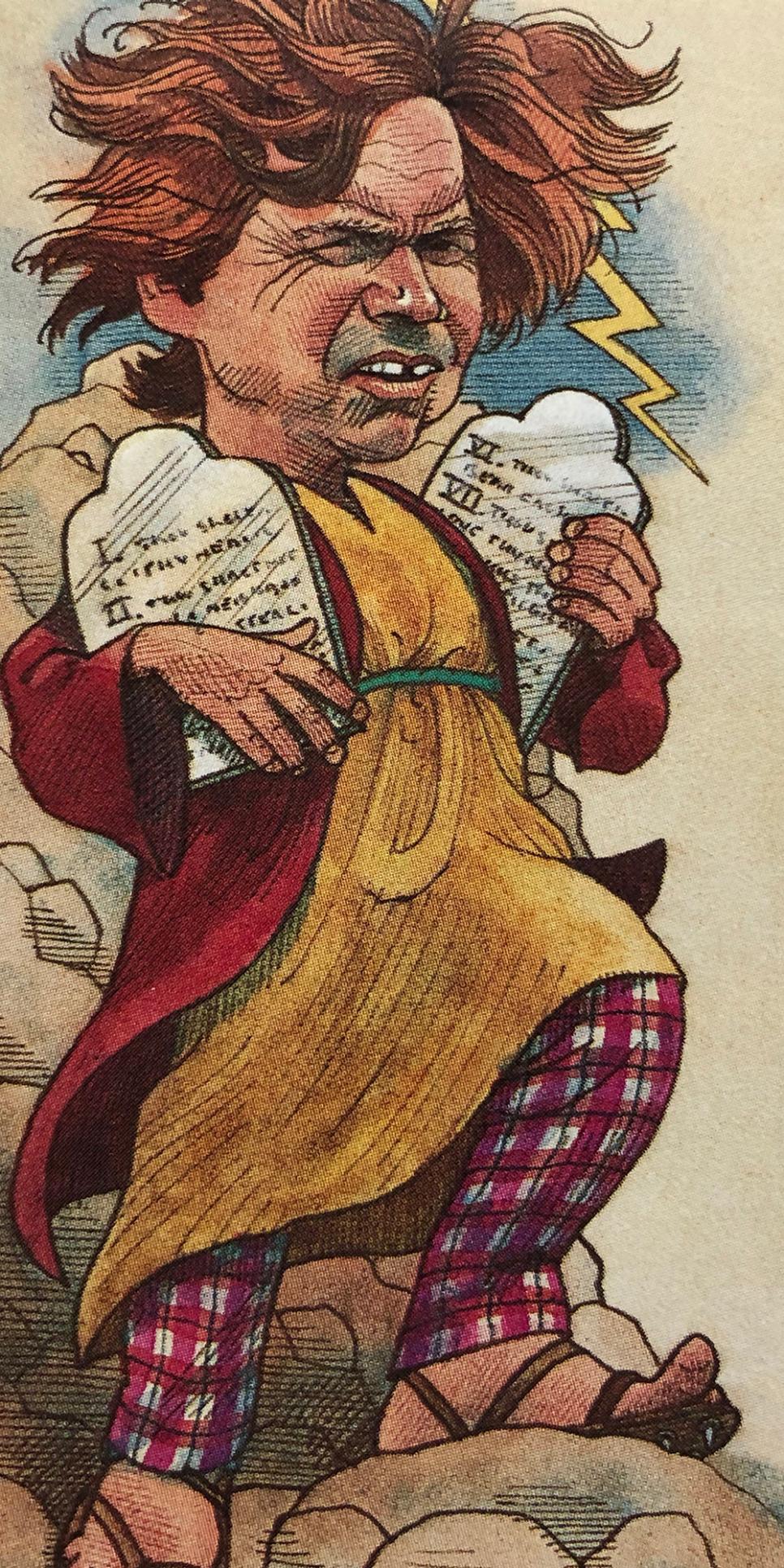

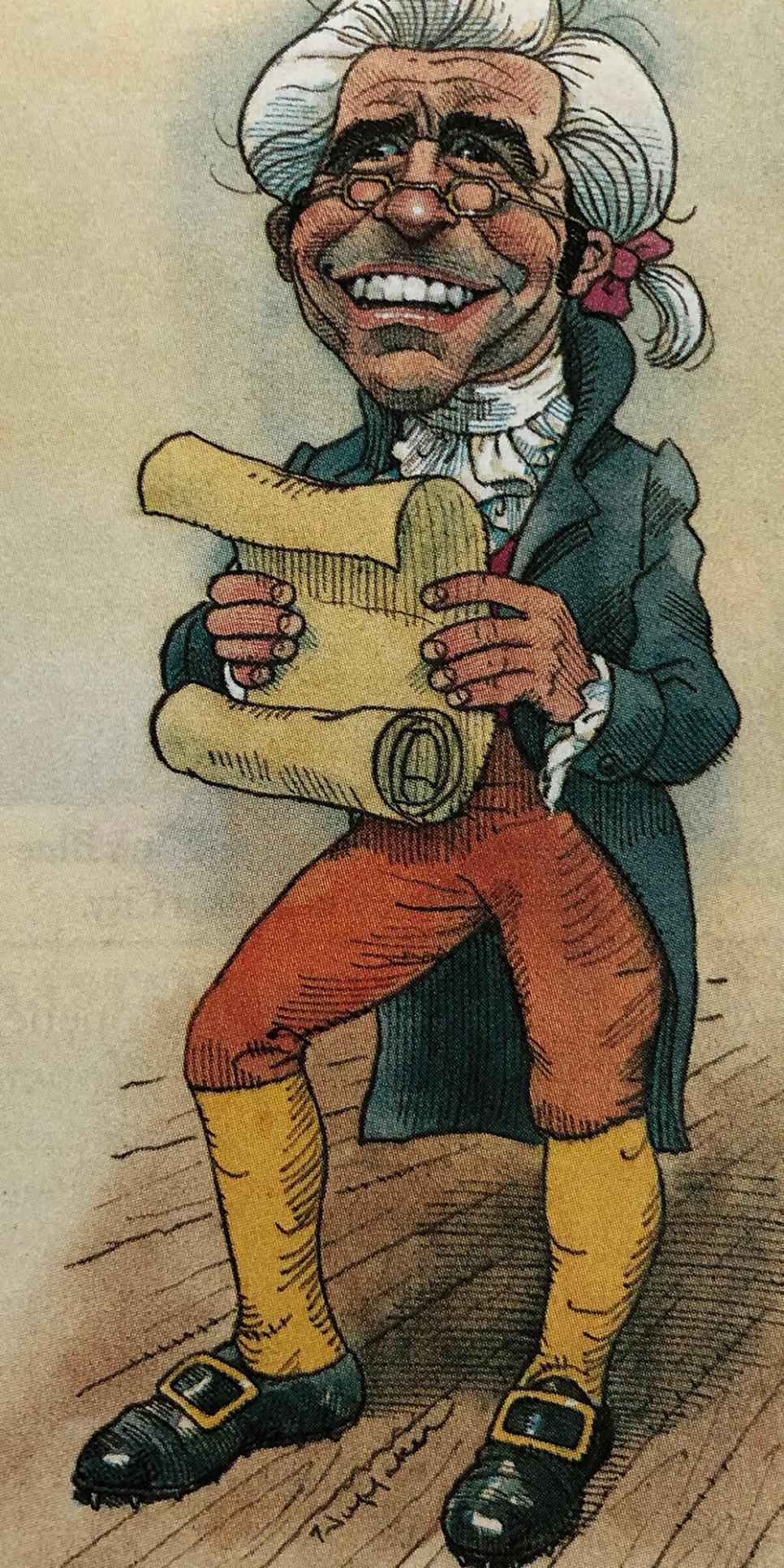

The rules: Are you a Tom or a Gary?

From the archive (April 1984): It depends on whether you think the rules are chiseled in stone or meant to be ‘interpreted’

Editor’s note: In celebration of Golf Digest's 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published. Catch up on earlier installments.

Through the years, many confrontations have erupted between top players on course—Hale Irwin accused Seve Ballesteros of gamesmanship, Phil Mickelson clashed with Vijay Singh over spike marks, Miguel Angel Jimenez and Keegan Bradley got into it over a drop—but the most infamous dispute occurred on Thanksgiving weekend 1983 during a skins game. Something happened on the 16th hole of live golf on NBC with $120,000 at stake, but it didn’t become known until after the event had concluded.

Dave Anderson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning sports columnist for The New York Times, was working on his story in the press tent when he needed to check a question and unknowingly stumbled into a heated conversation outside in a deserted parking lot. He overheard Tom Watson accusing Gary Player of cheating in front of the rules official Joe Dey with Jack Nicklaus as a bystander. (The fourth participant in the Big Four skins game, Arnold Palmer, was not at the scene.) The dispute was over whether Gary had improved his lie, moved some blades of grass, to hit a chip shot beside the 16th green.

Anderson filed his story that night, despite pleading from Dey that it was a private conversation. Anderson wrote: “From 30 feet away, Tom Watson could be heard saying, ‘I’m accusing you, Gary … you can’t do that … I’m tired of this … I wasn’t watching you, but I saw it.’ Gary Player could be heard defending himself, saying at one point, ‘I was within the rules.’”

Watson never backed off his accusation but later said, “My greatest regret, though, is that this private matter became a public incident.” Player defended himself, and for years golfers were split over who was right, the two eventually finding peace in agreeing to disagree. Peter Dobereiner, the esteemed British columnist for Golf Digest, who understood the game and human nature as well as anyone ever did, made sense of the incident with this essay, published in April 1984. —Jerry Tarde

***

No doubt there will be another Skins Game this year. Invitations again have been extended to Gary Player and Tom Watson, along with Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer. And no doubt the promoters and officials will have nervous palpitations over the possibility that Player and Watson will again clash over the Rules of Golf. The problem also could pop up on the PGA Tour when Player arrives this spring for his customary tune-ups leading to the Masters.

It will be recalled that last November [1983] a $360,000 shootout matched these four doughty golfing gunslingers at the new Desert Highlands Club in Scottsdale for the delectation of television viewers who were bored with the head-butting rituals of the rutting season, or NFL football, as it is sometimes called.

Skins is a form of golf gambling in which the players agree to play for a set amount, say, $1 for each hole. If one player wins the hole outright, he collects $1 apiece from the other three. If two or more tie for the hole, the money may be carried over and added to the pot for the next hole.

This TV version was not a genuine skins game because the golfers were playing for the promoter’s money rather than gambling their own. But whether you call it a skins game or an exercise in promoting sales of real estate, the Rules of Golf apply.

After the final round, Watson accused Player of violating Rule 13-2 by attempting to reposition a blade of crabgrass behind his ball before playing a chip shot. Player denied any breach of rule. Dave Anderson of The New York Times overhead their heated altercation, wrote about it, and the dispute became the subject of public knowledge and argument.

What were the rights and wrongs of this incident? Were there indeed rights and wrongs, or possibly two rights, or even two wrongs?

Half a millennium of history and half a world of geography separate the attitudes of these two players, and their tense confrontation represented a head-on collision between two fundamental philosophies. Because we are committed to one of the two philosophies, and line up behind either Watson or Player in our view of sport, it may be appropriate to examine in some detail the background of this gulf.

The origins of Watson’s approach to sport lie in ancient Greece, in the precursors of the Olympic Games. In historical fact, the athletes of the Pan Athenian games were professionals, amenable to bribery and not above rigging the results, but the English saw them as true-blue amateurs and paragons of honesty, integrity and fair play. These were the qualities that the English admired and adopted as the Corinthian ethic. The Puritans took a sanitized code of English moral values with them to the New World, and on these pillars of rectitude were erected the structure of middle-class America, from which Tom Watson was spawned.

Nobody had to instruct Watson that he must play the ball as it lay; that commandment was implanted in his very genes from generations of indoctrination that virtue is its own reward. You can tell a lot about a man from the company he keeps, and it is significant that one of Watson’s close friends is the former president of the United States Golf Association, Sandy Tatum, the apotheosis of the amateur ethic.

Watson is well-versed in the Rules of Golf. Indeed, he is coauthor of the second-best book ever written about the rules, but he does not need this knowledge. If you are imbued with the spirit of sportsmanship, fair play and not talking advantage, then you can play golf with no more than the iron rations of the original Thirteen Articles of the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers without running afoul of the law.

Player’s background is very different. He is the son of a nation that has had to overcome appalling hostility ever since the first representatives of the Dutch East India Company established a settlement on the Cape as a staging post for the merchantmen sailing to the Orient.

When the voortrekkers loaded their ox wagons and struck north, they had to combat the hostility of the climate, the terrain, disease and the Zulu armies. The laager mentality—to circle the wagons and shoot anything that the outside world sent against them, including the colonizing British Army—is endemic in the South African character, whether of Dutch or British origin.

Player’s inherited instinct to confront and defeat every obstacle in his path was greatly reinforced by his humble family background and his diminutive stature. He did not become a giant of golf by conforming to some nebulous code of behavior enshrined within the portals of Oxford and Harvard, a code that said you did not do this because it is simply not done, old boy. By instinct and his nature he challenged this mysterious ethic. His approach to the rule book is much like that of a man facing his demand for income tax. Where are the loopholes? Unless the law specifically forbids something, then that’s all right. Player looks upon the rules as the golfer’s Bill of Rights. Conversely, Watson sees the rules as the Ten Commandments.

The one rule that Player takes as his watchword is the one that proclaims that the referee’s decision is final. In Great Britain, it is reckoned that the ultimate examination for a novice referee is to get Gary Player in a rhododendron bush in the Suntory World Match Play Championship. Player’s reputation and intense personality have often proved intimidating, as when he said he proposed to chip out sideways and sought relief on the grounds that an advertising board impinged on his line of sight.

In the world of golf, one often hears accusations that Player is a cheat. The charge is ludicrous. He is meticulous in sending for the referee in doubtful situations, but he then presses hard for the maximum advantage. If referees have given him excessive benefits of doubt, then that is their fault, not his. Player’s conscience is clear; he simply takes what he perceives to be a properly professional attitude toward the rules. He’ll take what he can get.

It follows from this that it is not my purpose to put Watson and Player on trial and to give judgment that this one is right and that one is wrong. They are both right, which is why that confrontation at Desert Highlands was doomed to an inconclusive outcome. Both came away confirmed in their views that they were right and the other was out of order. Sparks always fly when an idealist collides with a realist.

Into which category do you fall? To help you decide whether you are a Watson or a Player, I have devised a simple questionnaire.

1. After hitting your usual blue-flamer down the middle of the fairway, a greenkeeper runs over your ball with his tractor, embedding it in the turf. Do you (a) remark that your next shot is going to be rather amusing, or (b) quote the Decision embodying the principle that a golfer is entitled to the lie his shot gave him and insist on a free drop?

2. Your opponent tees up his ball fractionally ahead of a line between the tee markers. Do you (a) remark casually on the next tee how difficult it is to judge the limits of the teeing ground with these fancy tee markers and how careful one has to be, or (b) immediately recall the shot?

3. The head falls off your putter during a match. Do you (a) continue the match unabashed, putting with your 1-iron, or (b) leave your opponent on the course while you fetch a replacement from the clubhouse?

4. Your ball moves while you are removing a nearby twig. In assessing whether you are liable to a penalty, do you measure with (a) the club you normally use in taking relief, i.e., the driver, or (b) your putter?

5. Your ball finishes in a dead stymie behind a tree. Is your first action on arriving at the spot (a) to assess your target area for a sideways chip, or (b) to cast around for signs of burrowing animals, casual water or grass cuttings?

6. Your opponent calls across the fairway that his ball lies among clippings and that he would like to take free relief. Do you (a) tell him to go ahead, or (b) inquire whether the clippings are fresh and obviously piled for removal?

7. Your opponent is clearly shy and a man who prefers to keep to himself and concentrate on his game. Do you (a) respect his wishes and play in funereal silence, or (b) deliberately engage him in hardy conversation all the way round?

8. You hook your drive into deep rough and observe a group of spectators beginning to search for your ball. Do you (a) immediately look at your watch and start monitoring five minutes [the time limit recently was changed to three minutes], or (b) walk to the area of the search and then note the time?

9. Your opponent is preparing to play a recovery shot from the shallows of a water hazard. As he takes the clubhead back, it catches a ripple and sends up a discernible spray. Do you (a) determine that unless he mentions the matter you will certainly ignore the lunatic ramifications of esoteric golf law, or (b) commiserate with him for having incurred a penalty for testing the surface?

10. Your opponent hits his ball into a bunker, and it finishes amid the coils of a somnolent rattlesnake. Do you (a) insist that he drop another ball in another bunker in approximately the same lie and distance from the flag, or (b) reassure him that the steward in the men’s bar keeps the snakebite serum in readiness for mishaps?

All the procedures suggested in the alternative answers are perfectly lawful. If you score more “a’s” than “b’s,” then you are more of a Tom Watson than a Gary Player; you are an idealist who believes that the game is bigger than the winning or losing of it. If you rate a preponderance of b’s, then you are a true competitor; in whatever walk of life you choose you will go far.

It is generally supposed that amateurs are “a” people and professionals are “b’s.” In golf, that assumption is less than fair. I would judge the vast majority of professional golfers to maintain a happy balance between “a” and “b,” scrupulously accepting the debits as well as the credits of the rules and at the same time honoring the unwritten laws of sportsmanship. It just so happens that in Watson and Player we find attitudes that are polarized at the extremes of the scale, the Idealist and the Realist.

When these two forces come into conflict there is usually no contest, the Realist habitually prevailing, which is why it is so refreshing that Watson is successful in the pragmatic world of professional golf.