That 70's Show

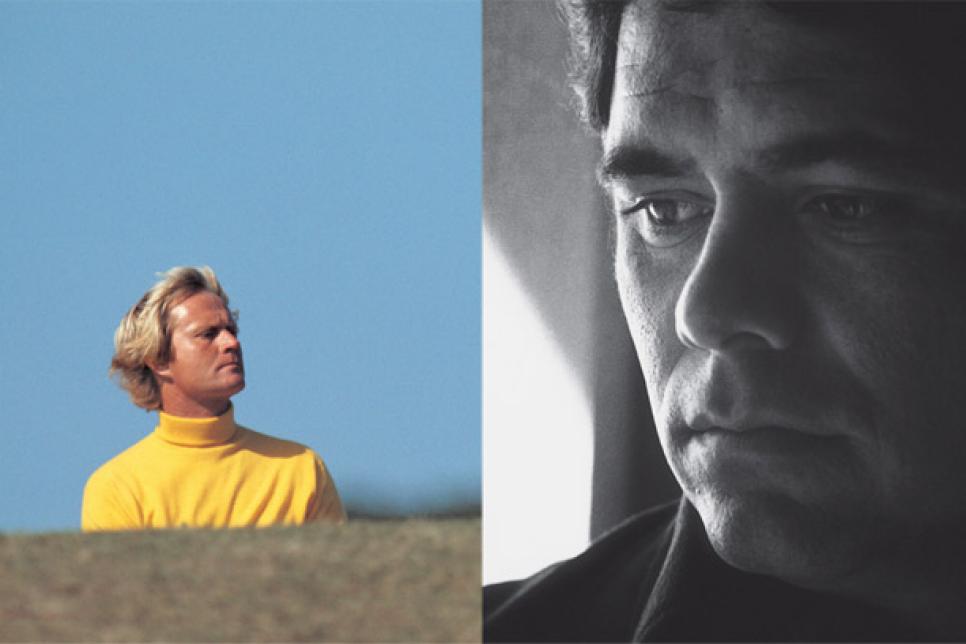

Jack Nicklaus at the 1978 British Open at St. Andrews; Lee Trevino in El Paso on Thanksgiving Day in 1972.

However old you happen to be, provided you're older than Rory McIlroy, one thing is certain. The athletes of your youth were better than they are now. Never mind that, in every sporting contest measurable by watch or yardstick, today's practitioners are running laughably ahead of yesterday's. Johnny Weissmuller's gold-medal swimming times in Paris (1924) and Amsterdam (1928) wouldn't impress an 8-year-old girl now.

So how can it possibly be true--in statistically precise but otherwise incalculable sports like baseball--that Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio, Hank Aaron, Ted Williams or even Babe Ruth is still the ultimate ballplayer? Or that Jim Brown, Bobby Orr, Sugar Ray Robinson, Pelé or even Michael Jordan continues to be No. 1?

Golf, only superficially marked off by the foot and yard, has a dimension that means more than any of its cold numbers. Genius. Every one of the supporting actors in the Tiger Woods saga was bigger, stronger, longer and more athletic than Lee Trevino, but their combined genius quotients didn't amount to his. "He was good," Jack Nicklaus says. "He was very good. And he was smart. You know, I always thought Trevino and Ben Hogan were the two best ball-strikers I ever saw. And I think Trevino was a lot like Hogan in how he figured out a golf course and how to play it."

There was a time, before instructors swarmed golf like locusts, when every tour pro figured out a golf course and how to play it for himself. As a result, most of them were identifiable from three fairways over by their singular swings (see: Doug Sanders, Don January, Chi Chi Rodriguez, Hubert Green, Raymond Floyd, Miller Barber...) and recognized as professionalshotmakers who knew both how to play and how to win.

"How to play is right," Floyd says. "That's the key. You got it."

"We played golf," says Green. "Today's players just golf. It's a semantic distinction, but I think you know what I mean."

They had no choice but to win if they wanted to make a significant living on the PGA Tour. In Nicklaus' most prosperous year, 1972 (seven victories, including the Masters and U.S. Open), he earned a total of $316,911, roughly what 11th place paid in the 2012 FedEx Cup.

"You guys just don't know how to win," Captain Nicklaus scolded his Ryder Cup team between the closing ceremony and the dinner in 1987, when a second straight European victory flipped the balance of power. "How many matches were we leading going to 18 and didn't win them? Look at you, Payne Stewart. You make all this money on tour, but how many tournaments have you won? Why don't you win more? You guys need to learn how to win, or you're going to continue getting beaten in this thing."

"There wasn't any sugarcoating on it," Stewart said 12 years later. "I'll tell you, that speech was good for me." He promptly won the first of his three major titles in a heartbreakingly short career.

Could it be that golf had its own greatest generation, perhaps made up of those diverse and decorated individuals and characters who at least dipped a toe in the 1970s? Before the new golf ball and the age of titanium?

"Well, I guess everyone thinks their own generation was the best generation," Nicklaus says. "So, let's start with that premise, that I'm obviously partial because that's when I played. I don't want to be so presumptuous as to say it was better than today or better than before us, or whatever. But it was pretty good. It was a pretty good time. We had some pretty darn good players."

*The event in 1970 that had the most profound effect on golf might have been the death of Charlie Nicklaus at 56. It's a father's game. "When Dad died, I realized two things: how short life really is and how much I'd let him down," Jack says. "The last three years he was alive, I didn't work as hard as I should have. I just sort of went along, winning a bunch of tournaments but no majors. When I analyzed it, I could see that my dad had lived for me, for what I did. That was what he really enjoyed, what brought him his greatest pleasure. I sort of kicked myself in the rear end, got to work again and won the British Open." *

Out from under Charlie's sway, "Fat Jack" retooled himself into a model for clothes and a mold for golfers--towheads shaped like 1-irons. For the rest of the decade, an avid golf fan was defined as anyone who could tell Johnny Miller from John Mahaffey from Ben Crenshaw from Bill Rogers from Jerry Pate. To separate himself, Pate took to jack-knifing into water hazards.

BIG WINNERS

The litany of '70s saints only starts with Nicklaus, Trevino, Floyd, Green, Miller, Mahaffey, Crenshaw, Rogers, Pate, Gary Player, Billy Casper (the most under-praised great player in history), Gene Littler, Julius Boros, Tom Watson, Hale Irwin, Seve Ballesteros, Tony Jacklin, David Graham, Lanny Wadkins, Dave Stockton, Larry Nelson, Fuzzy Zoeller, Tom Weiskopf and their 82 major championships.

"Don't forget Palmer," Jack says. Eighty-nine. "He didn't have a major in there, but he was still playing and still very relevant."

"Arnold was the greatest of all," Floyd says, "the one who kicked off everything, really. He was the swashbuckler who showed television how to do it. I lost a playoff to Arnold in the '71 Bob Hope at Bermuda Dunes [Palmer won the same tournament two years later for his final victory on tour], and I can tell you, there weren't many people on my side." Almost including Raymond.

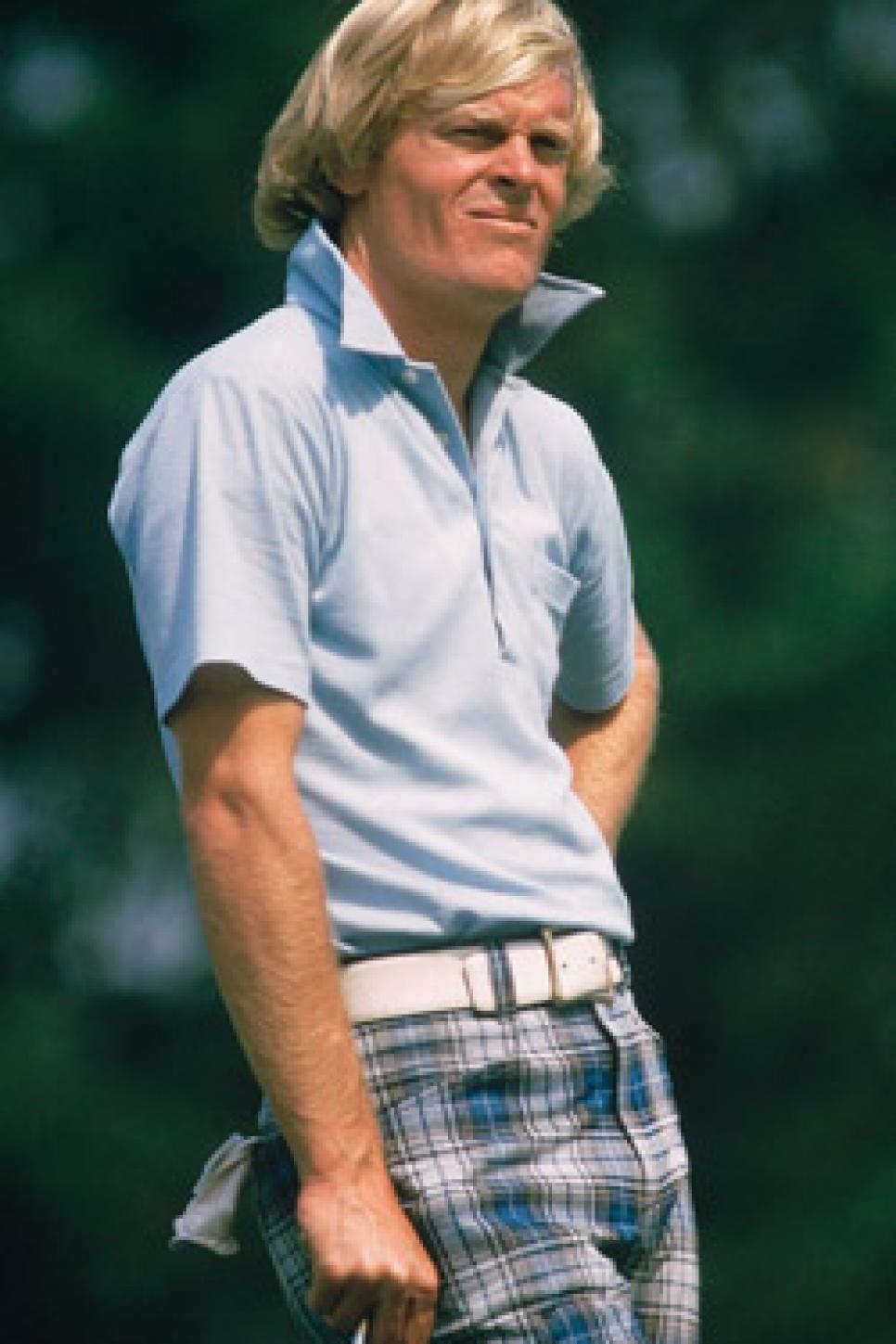

Arnold Palmer shows his flair in 1973, the year he earned the last of his 62 PGA Tour victories.

Photo: Augusta National/Getty Images

To Floyd, Palmer represents something valuable that is gone from the game. Or, if not entirely gone, at least diminished. "At my first Masters, I wore a pair of madras pants. 'C'mere a minute,' Arnold called me over in the locker room. 'Son, this isn't just another golf tournament,' he said. 'This is different. This is special. Wear a more respectful pair of pants tomorrow.' I did, the next day and from then on. Do you think anyone today would do that?"

Tom Watson calls this "leading from the top." Tom turned pro in 1971 but took three years to grasp Sundays on tour (and even a little longer when it came to U.S. Opens). "At Colonial one time, where they had free beer in the locker room, I was sitting around with a bunch of the guys when Chi Chi Rodriguez walked in. He started going on and on about how well I was playing and what a good young player I was. Julius Boros looked up at me and said, 'I'd like to have the money you've pissed away already.' "

You'd think that would have stung Watson, but it didn't. He took it as coming from the top. In fact, Tom considered it a kind of compliment, a tough one. "He was telling me, 'You're too good a player to settle for just good results. Get back out there and win.' "

*An untold story of the decade, and for decades to come, was the spiteful treatment foreign pros received at the hands of the PGA Tour's rank-and-file, small, provincial, envious men like Dave Hill. Hill finished second in the 1970 U.S. Open at Hazeltine in Minnesota, a course he loathed ("All it lacks is 80 acres of corn and a few cows"). The winner was a truck driver's son from Scunthorpe, England, Tony Jacklin. *

It must also be said that not every American player looked at the internationals and saw prize money leaving the country. There was at least one incident of amazing kindness. On the morning of the final round at Hazeltine, when the leader Jacklin opened his locker, he found a one-word note from Tom Weiskopf. It read: "Tempo." Carrying that thought with him all day, Jacklin beat Hill by seven strokes.

EUROPE'S VERSION, AND ANOTHER ERA

'Our greatest generation," says Roger Chapman, speaking for the European Tour, "was probably a decade behind yours: Lyle, Olazabal, Langer, Faldo, Woosnam, the core of the Ryder Cup team. Of course, it all traces to Ballesteros in 1976 [when a 19-year-old came out of Spain and nowhere to tie for second at Royal Birkdale] and to his first Open Championship, in '79. On Europe's side, everything goes back to Seve. He was our inspiration. He was our leader." After a marathon run as a bridesmaid, the Englishman Chapman broke through last season at the age of 53 to win the Senior PGA and the U.S. Senior Open. Those sweet summer breezes blew the dust off an old memory.

"I played with Seve early in my career, in Switzerland," Chapman says, "and I was missing the cut--a few shots over the cut line with four or five holes to play. I'm sure I was looking a bit down. He came over to me and whispered, 'Hey, player, why you not try?' 'I'm trying,' I told him. 'Try harder,' he said. 'There are so many birdies out here. Come on!' All of a sudden I go birdie, eagle, birdie, par to make the cut on the number. I look across the green, and there he is, pumping those fists. Not for himself, for me. Fantastic. I can't tell you what it meant to me then, and now."

Recalling a famous 3-wood shot Ballesteros hit 245 yards out of a steep bunker, over a tall lip, beyond a treacherous water hazard just short of an 18th green to halve a match at the '83 Ryder Cup ("the finest shot I've ever seen," Nicklaus said at the time), Chapman issues a challenge. "Go to PGA National," he says, "walk into that bunker and have a look for yourself. Comparing eras is never entirely fair, but you tell me who today could see that shot let alone pull it off."

Photo: Bob Thomas/Getty Images

*On Thursday at the 1972 Masters, only two men broke 70: the eventual winner, Nicklaus (68), and Sam Snead (69), who turned 60 years old a month later. That August, Snead finished equal-fourth at the PGA (three strokes behind the champion, Gary Player), where the following year Sam tied for ninth, and the year after that, third. He was 62 by then, putting sidesaddle. *

"I just hit a little Cutty Sark in there," he'd say in the pressroom for the enjoyment of the writers, even though they knew he seldom imbibed. But outside the Augusta National clubhouse, under a spreading oak, Snead reached out for a questioner's sleeve and pulled him close enough to whisper in his ear, "If Hogan could win another Open putting sidesaddle, he wouldn't do it. It looks so God-awful."

THE SWING VERSUS PLAYING THE GAME

Consider some of the changes that have come about in the swing, the equipment, the culture, the courses and the money.

"The greatest generation all had wildly different swings," says Bobby Clampett. "Upright swings, flat swings, shut faces, open faces, laid off, across the line--Larry Nelson was across the line--past parallel, short of parallel, big hip turn, small hip turn, inside the backswing, outside the backswing, every variation you can think of. But what they created at impact was identical."

An honored amateur in the late '70s, Clampett had a few brushes with history as a pro, opening 67-66 at Royal Troon in 1982, eventually wandering into television. There, his access to slow-motion tapes from CBS' cameras amounted to a doctorate in the golf swing.

"I think the modern search for the perfect swing is killing golf," he says. "When a student is 10 years old, fine, give him or her the fundamentals, and install a style if you have to. But when they get to be 13, leave them alone. Let them go out and play. Like the greatest generation did, allow them to become their own instructors. Jack Nicklaus didn't live with Jack Grout. Stan Thirsk wasn't on the road with Tom Watson. I sometimes wonder if the luckiest guys on tour today aren't the guys who've never had a lesson, like Bubba Watson. Or Jim Furyk, whose dad was a club pro smart enough to know when to teach and when to get out of the way."

As a junior, Clampett competed against many kids whose fathers were teaching pros. "You have no idea," he says, "how much pressure there is on a PGA professional to make his children models and examples of the perfect swing. I grew up with a lot of those kids. Gorgeous, gorgeous swings. Couldn't play a lick."

By Bobby's lights, today's PGA Tour is crowded with fevered prospectors panning madly for fool's gold.

"Take Charles Howell III," he says. "Good pro. Great kid. But I consider him a victim of this generation. Instead of going out and learning how to play shots, how to score the ball, how to consistently get four or five feet nearer to the hole on approaches, how to hit one more fairway a round, how to chip it two feet closer, how to read the greens, how to putt to a better speed, these guys are constantly polishing their beautiful swings. For the old guys, the greatest generation, those little scoring things were all they worked on. Give them a lie in the rough, and they'd say to themselves, OK, that's going to jump eight yards, and then it's going to release seven more--no, seven-and-a-half. So, let's take fifteen-and-a-half off. The current generation says, Uh, I think it's going to jump a little. I don't know."

Tiger Woods arrived already understanding how to play, obviously. Is it possible that he has since been swept up in the communal quest for the perfect swing?

"When Tiger came out," Clampett says, "besides being the best putter anyone ever saw, his real skill was knowing how to play. He won the Masters by 12 with a club that was too steep, across the line and shut at the top. Then he won the U.S. Open by 15 with what most considered the ideal plane, the ideal clubface. Then he won the British by eight laid off at the top and open. What does all that tell you?"

That Woods might have turned away from his own genius to join the crowd in pursuit of a grail.

Eighteen of Miller's 25 tour wins came in the 70's.

Photo: John D. Hanlon/Getty Images

*Johnny Miller's specialty was shooting nothing in the desert, but when he shot 63 on a soggy course to win the 1973 U.S. Open at Oakmont in western Pennsylvania (Palmer country, with Arnie and John Schlee in the final twosome), the ground trembled. At Winged Foot in 1974, vengeance was the USGA's. Forrest Fezler's nine-over-par score lost that Open by two strokes to bespectacled Hale Irwin, who hired a local schoolboy to caddie. *

In those days, caddies didn't line up the putts like Bones Mackay. Nicklaus' fuzzy-wigged bagman, Angelo Argea, whose motley mustache was an amalgam of disappointment and nicotine, never read a putt or pulled a club for Jack. Angelo was just good company.

The evening of the first round at Winged Foot, Argea was sitting with his back to a tree near the press parking lot, smoking. "All I can tell you," he said, "is that, on the very first hole of the tournament, we had an 18-footer for birdie and a 28-footer for par. Thanks a lot, Johnny Miller."

THE EQUIPMENT AND PHILOSOPHY

Peter Jacobsen, another '70s man who veered into TV, says, "I remember one time Craig Stadler found a driver in a barrel. Craig had no idea what the shaft was. But he liked it. He hit it long, and he hit it straight. I think he won his Masters with it. Nowadays, you go and get fitted for clubs just like you do for a tuxedo before a wedding. You walk into Mister Formal, and they measure you all over. Here's your shaft, here's your head, here's your ball, here's your grip size, here's your launch angle, here's your spin rate, and you put on your cummerbund and walk out of the store. It's completely automated. We all do it. Why wouldn't we?"

A better question might be: Why shouldn't they?

"Now you're talking philosophy," Jake says. "What you mean is, what have we lost? Well, I'll tell you.

"There's no search. There's no journey. I've always agreed with Michael Murphy [Golf in the Kingdom] that the game of golf is less about the contact point of the club and the ball than it is about the in-between, the walking from one shot to the next. It's not the shots themselves. It's what goes on in your mind between shots. I'm certain this was truer back in the '70s than it is today."

"I have an old set of hickories," Sandy Lyle says, not that he goes back to hickories. "I pull them out every now and then just to wind back the clock a little." He is an English-born Scot, an Open, Masters and Players champion, who was the recipient of the second-best compliment ever paid a golfer. The first was Bobby Jones' reference to young Nicklaus playing a game with which Jones was not familiar. Then Seve said this about Lyle: If everyone in the world played his absolute best, Sandy would win.

"I get out one of those old, softer golf balls," Lyle says, "and bash it around for a little while with my hickories. Just to remind myself where we came from. Just to try to keep a little perspective."

"I know what he means," Nick Price says. "I had two hickory clubs in the hodgepodge bag I started with as a boy. They were hard to hit, but they were fun. There are players on tour now who have never hit a wooden-headed driver. Think of that. And some of their new hybrid clubs have larger heads than our old persimmons. It's a different game."

They were friends at the beginning and at the end. In between, Nicklaus and Palmer were blood rivals. "I can remember one night," Jack says, "when we got to kicking each other under the table. I don't know why. I kicked him. He kicked me. Neither would give. We ended up with the biggest damned bruises. We used to do the stupidest stuff."

*In 1975, Nicklaus won two majors and, in that Ryder Cup era of Sunday-morning and Sunday-afternoon singles matches, lost twice in one day to pipe-smoking Englishman Brian Barnes. Palmer was the American captain. *

Either Jack or Arnie might have won the U.S. Open that summer at Medinah had they not been paired together in the fourth round. Caught up in each other, they lost sight of Lou Graham and John Mahaffey. "That happened a lot," Palmer says. In an unusual dual postmortem, Palmer-Nicklaus (hyphenated like Dempsey-Tunney) were rattling off their birdies and bogeys side by side in the press tent when the vinegar between them bubbled over. Nicklaus was bemoaning his closing three holes so pitifully that Palmer finally had enough.

"Why don't you just sashay your ass back out there," he said, "and play them over?"

THE CULTURE AND THE ATTITUDE

It's a different world. "I'm the captain of the U.S. Ryder Cup team in 1989," Floyd says, "and one of my players didn't own a sports jacket until we gave him one. I am not kidding. And, you probably won't believe this, but three of the 12 did not know how to tie a necktie. I had to tie three ties for my Ryder Cup team before we went out to the opening ceremonies."

Of course then, the match was played to a tie.

"Sometimes," Floyd says, "I wonder what Dan Sikes ["the Golfing Lawyer," a fastidious dresser who died in 1987 at 58] would think of the bluejeans today's players put on in the locker room before they head out in their courtesy cars to rejoin their entourages."

"With their caps turned around backward and their facial hair," Irwin adds. "I don't blame the young players, though. Not really. The game and the world are both constantly evolving, and nobody has any control of where they fall on that line. Thankfully, virtually all of today's kids are as respectful as they can be toward the game of golf. It's just that, almost more than anything else in society, golf used to champion a certain upbringing and discipline. To some of us, we hate to lose that."

"I don't know," Bernhard Langer says, "it could be that it's just more fashionable now to wear a cap backward than the right way around. And, you know, they're making some pretty good-looking jeans these days. Expensive, too. I'll agree that golf was different back in what you're calling a golden age, but I'm not so sure it was better. Certainly everything wasn't better. They played golf, and then they went to the bar and got drunk, half of them, whatever. To me, that's not being a professional."

*After three rounds of the 1976 Masters, Floyd led Nicklaus by eight strokes. Before Raymond sat down in the Bartlett Lounge of the old green Quonset hut that housed the press in Augusta, he took the time to meet the gaze of seemingly every writer in the room. Exactly like when he chipped from a fringe, Floyd had a look in his eye that could bore a hole in a Quonset hut. "Anybody here," he asked dryly, "betting against me tomorrow?" *

That tournament was over.

THE COURSE AND THE COMPETITION

'Look at what the modern equipment has done to the great old golf courses," Price says. "It's made many of them somewhat redundant. What would that legendary 1- or 2-iron Hogan hit at Merion be now? A 9-iron or a wedge? To me, that's a sad thing. I'm a traditionalist at heart, and I just hated the quantum leap the equipment made over such a brief space of time. Say, from about 1997 to, like, 2008. It just went through the roof. The powers that be should have seen that coming and tapped it back. Other sports haven't had to change their arenas. Golf has.

"Give a Mark McGwire or a Sammy Sosa or a Barry Bonds a titanium baseball bat that's 2½ or 3 times the diameter of the old wooden one and is 2½ inches longer and weighs less. Do you know what would happen?"

They would kill a pitcher.

"That's right. And the golf course is the pitcher."

Photo: Augusta National/Getty Images

*On the Ailsa course at Turnberry in Scotland, eight eventual Hall of Famers (Watson, Nicklaus, Green, Trevino, Crenshaw, Palmer, Floyd and Miller) finished in the top nine at the '77 Open Championship. But the best two were at least 10 strokes better than the rest. It all came down to a 40-footer for Nicklaus and a three-footer for Watson on the 72nd hole. *

"We've got him now," whispered Watson's plaid caddie, Alfie Fyles.

"No, he's going to make it," Tom said.

He did, and Tom did (for his second major of the year), and they walked off the green in each other's arms.

THE MONEY AND DESIRE

'Money changes everything," Don January says. "Once, you had to be a worldbeater just to make a living at tournament golf. You don't have to be even a real good player to make a hell of a lot of money now."

"Money corrupts desire," Tom Watson says.

"My son, Brent, doesn't even play anymore, he's made so many good investments," says Al Geiberger. "He's on easy street. Meanwhile, I'm broke." Al's only half-kidding. "Brent made almost as much in one tournament, Greensboro [$828,000], as I made in my whole career [$1,265,000]."

It was a handsome but unlucky career that brought Geiberger only to the foyer of the Hall of Fame. "Mr. 59," the Roger Bannister of that barrier, won a PGA, a Players and twice was runner-up at the U.S. Open, when against all logic Orville Moody two-putted his way home at the Champions Golf Club and Jerry Pate drew almost the only suitable lie at the Atlanta Athletic Club from which to hit the 5-iron of everyone's dreams. "But I also had three marriages," Al says, "like Trevino. If you're going to have three wives, you're going to need three fortunes."

How many women named Claudia have you known in your lifetime? Trevino married two of them. That and Johnny Vander Meer's two consecutive no-hitters are the records that will never be broken. To beat them, you'd have to pitch three Claudias and three no-hitters.

Geiberger says, "I remember flying across the country to play in my first $100,000 tournament. I remember choking for it, too.

"But then there are a lot of other memories that money can't buy."

*Near the end of the decade, Trevino finally threw in a good round at the Masters, a 69. He won all of the other majors twice over, but the National was the course he never figured out. *

Nicklaus says, "The only thing I didn't agree with Lee on was that he said he couldn't play Augusta. He got that in his head, and I think that was wrong." It certainly had to do with right and wrong.

In 1972, an associate of Trevino's, a young black man named Neal Harvey, was tossed off the course during a practice round for wearing the wrong day's credential. Trevino came over from the fairway to try to intercede with the Pinkertons, to no avail. The next day, he boycotted the clubhouse, changing his shoes at the car.

"Who provides your shoes these days, Lee?"

"I buy my own shoes. Where were they when I needed shoes?"

There were years then when he was qualified to play in the Masters and didn't.

ANOTHER VIEW

'I think every generation has its own greatness," Corey Pavin says. "You could define this current generation by the equipment or by the fact that everyone is trying to make the same swing. And then you could say that they don't get down in the dirt as much as the guys you're talking about, or that they don't have to find it by themselves. Fair enough. If you want to say yesterday was more about feel, and today is more about power, I'll buy that. But I don't agree that the winners are so very different. Tiger, Phil and Ernie all love to win, hate to lose, and will do everything possible to get the ball in the hole as fast as they can. That's always been the definition of a great player."

Corey thinks Phil is as much like Seve as Seve was like Palmer. "Dedicated to taking a lot of chances," he says, "to trying any shot they can think of to recover, to playing golf absolutely by the seat of their pants." Furthermore, he wagers, "if you look up golf articles from the '30s and '40s, you'll probably find a lot of complaints about the advances in equipment and the ball going too far. 'And where have all the characters gone?' "

"There have always been and always will be characters," Langer says. "Look at Ben Crane. Nobody would think he is who he is, but that's who he is."

You can't say it any better than that.

*"Columbus went around the world in 1492," Trevino paused in his warm-up to say. "You know, that isn't a lot of strokes when you consider the course." *

A PORTRAIT OF GENIUS

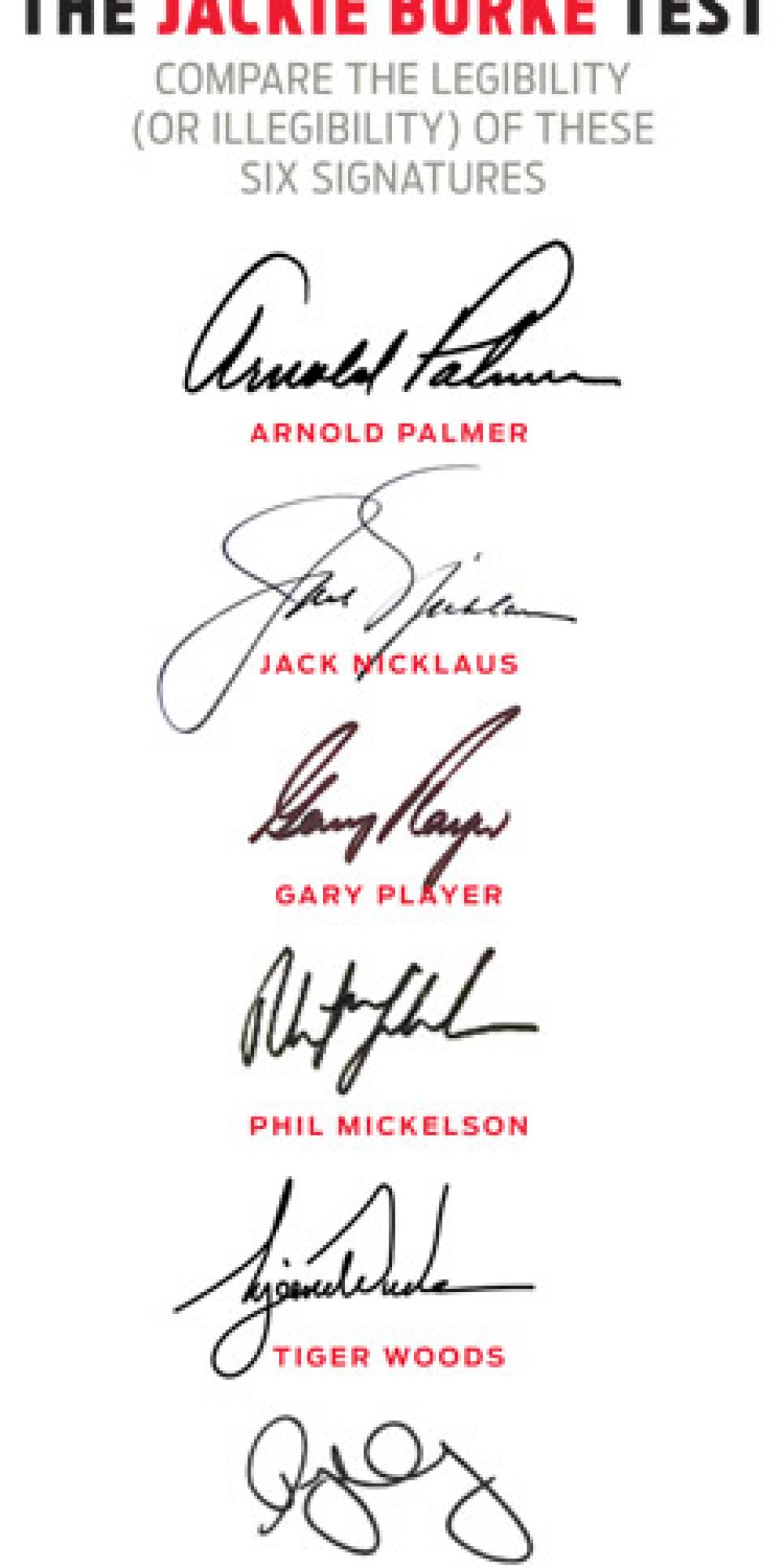

'I'm coming up on 9-oh January 29," says the Masters and PGA champion, Jackie Burke. "Ninety years. So I guess I've seen a little golf since I sat down on my dad's bag and listened as he gave his lessons. I captained Palmer, Nicklaus, Casper, Trevino and that crowd in the '73 Ryder Cup, so I know the era pretty good. You wouldn't be able to guess one of the things I really liked about them: You could read their autographs. They were legible. To me, that showed a decent consideration, to the public. Heck, in those days, that was about the only thing they had to do except not drop dead at a Ryder Cup."

When Jackie's team arrived at Prestwick, Scotland, in an early-morning rain, 10 of the players went straight to bed. Trevino and J.C. Snead, Sam's nephew, went to the practice tee at Muirfield. One of about 30 spectators standing behind Trevino was a 13-year-old Scot named John Huggan, who five years later would be the Scottish Boys champion, and 40 years later would be a flinty golf writer who doesn't like to let on how much he loves the game. But sometimes he can't help it.

"Trevino kept calling his shot and then hitting the shot," Huggan says. "The best part was that there was a small stick stuck in the ground about 100 yards away. He went, 'Watch this.' Then he carved a little wedge miles away up in the air, seemingly into the clouds, and it came down two feet from that stick. Then with the same club he deliberately thinned a ball along the ground and it stopped right next to the stick. I mean, tell me there's one guy on tour who can do that now."

No, Trevino was a genius.