From the magazine

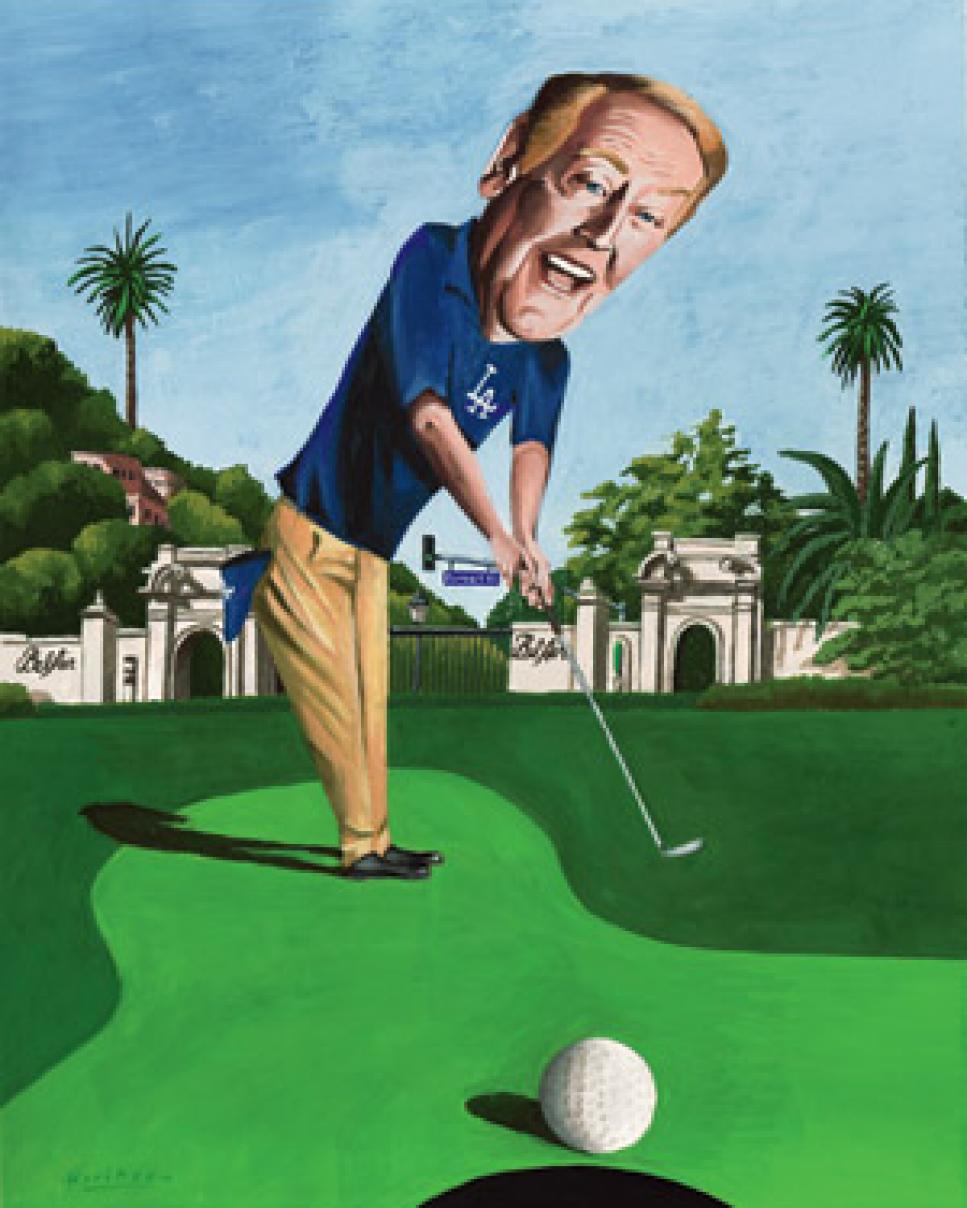

My Shot: Vin Scully

An American icon brings his best stuff on Sandy Koufax, a hole-in-one, striped neckties and the delicious silence of golf.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Famed broadcaster Vin Scully died on Tuesday at age 94. Known by most sports fans as the voice of the Los Angeles Dodgers for more than 50 years, Scully also spent time in the 1970s and 1980s doing play-by-play coverage of golf for CBS and NBC, including working at the Masters from 1975 to 1982. Scully sat down for this My Shot interview with Golf Digest that appeared in March 2012.

• • •

ON MONDAY the week of a long-ago L.A. Open at Riviera, several pros came over to Bel-Air to play the course. I wanted to get in nine holes that day and was playing alone. When I got to the par-3 third hole, three of the pros were on the green and waved me up. Even from a distance I could see the doubtful expressions as they watched this solitary left-hander standing over the ball with his 5-iron. There was pressure, and all I could think was, Keep your head down, and don't worry where it goes. I hit it reasonably well. The ball hit the green and rolled into the hole. There was a stunned silence. I shouted the only thing I could think of at such a moment: "Mind if I play through?"

OF COURSE the pros wanted me to join them. The next hole is the No. 1 handicap hole, a tough, uphill par 4. I parred it. The next hole is a good par 3; I just missed a putt for a birdie. As we walked through a tunnel on the way to the sixth tee, one of the pros sidled up and asked, "What's your handicap?" I told him I was a 12, and he gave me sort of a funny look. But the rest of that nine holes was a disaster.

SOME PEOPLE DIE twice: once when they retire, and again when they actually pass away. Fear of the first one is a big incentive for me to keep working. [Scully is returning for his 63rd season with the Dodgers.] Players, writers, people who work at the ballpark and front office, when I quit I know I'll never see them again. I've never been the type to come to the ballpark and hang out; I've gone to one game in the last 60 years that I wasn't working. I keep working because I don't want to lose my friends.

AS FOR GOLF, I've never taken my game seriously. I'm not much of a competitor. I'll play for a couple of bucks, but not enough to where I'll grumble if I lose. My handicap has never been lower than 12. I love to play, love the banter and the fact I get in some exercise without running, without killing myself. And if I shoot in the 40s, well, that's a bonus.

THAT A KID from the Bronx would ever play golf at all is unlikely. But golf is filled with unlikely people. I took up the game shortly after the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles after the 1957 season. I joined Riviera and then joined Bel-Air in 1970 when they conducted a drive for younger members. Which was flattering, considering I was 42 at the time.

I MISS my friend Jim Murray. Jim was a great sportswriter and an avid golfer. He thought of Riviera as his cathedral, and golf as his religion. One day we were playing at Bel-Air. There's a bridge that spans a canyon on the 10th hole there. I look back, and Jim is fussing with his bag. He retrieves a ball and drops it into the canyon. I asked him what he's doing. "I'm appeasing the golf gods," he says.

FOR AN ETERNITY my low score was 82. Then at Bel-Air one day, I hooked up with three very good golfers. It elevated my game, and I shot 77. I am not one to cling to the past, but it was Camelot, never to be seen again.

THERE ALWAYS was a great sense of anticipation at the top of the Masters broadcasts. From the tower overlooking the 18th green, I would do the opening. I can hear Frank Chirkinian, the producer, as though it were yesterday. Through my headphones I would hear the countdown, "Five … four … three … two … " and then Frank would boom, "Sing, Vinny!" and off I'd go.

WHEN JACK WHITAKER referred to the crowd at Augusta as a "mob" in 1966, the club chairman, Cliff Roberts, was offended. Whitaker was let go from the Masters team, and eventually I came into the job. There definitely were guidelines on expressions you were not to use. You said "patrons" instead of "gallery" or "fans," of course, and there absolutely was no mention of prize money.

EARLY IN THE WEEK of the 1975 Masters, which was to be my first, I was in Cincinnati doing the Dodgers and Reds. I got a call from Frank. "Mr. Roberts wants to meet you before the Masters starts, and that means right away." Apparently, when Mr. Roberts was informed that Vin Scully was to work the 18th hole that year, he replied—a little skeptically—"You mean the baseball feller?" He wanted to see me for his reassurance. But there was a problem. There was no way I could get a commercial flight down to Augusta, meet with Mr. Roberts and get back in time to do the Dodgers-Reds game. That was not going to satisfy Cliff Roberts. He found out that Arnold Palmer's private jet was being serviced in Indianapolis. Frank somehow gets it over to Cincinnati. Next thing I know, I'm getting out of Arnold's plane in Augusta and meeting with Mr. Roberts, who was very affable. He didn't mention Masters do's and don'ts at all. He just wanted to meet me. And he got me back in Cincinnati in time to do the game.

SANDY KOUFAX was special. For a five-year period, he was the best I ever saw. He's the only pitcher who would come to the mound and after two pitches give me the very strong impression that he might pitch a no-hitter. Not every time, but there were occasions where he'd throw a fastball I could see moving from all the way up in the booth, followed by his curve, which [catcher] John Roseboro called "the Yellow Hammer," and you knew he had a chance.

SANDY PUT ME through a lot of pain one time. He plays golf left-handed, and once I borrowed his clubs while we were on the road. He has huge hands; he can wrap his left thumb and middle finger around the equator of a baseball and nearly make them touch. So his grips were oversize. And he had gobs of lead tape on his irons. I couldn't hit these clubs at all. But I was determined and really went after one. I hurt my wrist badly on that swing and was in tremendous pain. Dr. Robert Kerlan, the Dodgers' team doctor, invited me to the dressing room for a cortisone shot. The players all gathered around; I think they wanted to see me cry. I took it like a man and said, "I'm OK." But on the drive home after the game, it felt like someone was holding a blowtorch to my wrist. I told Sandy I would never use his clubs again.

THE CRACK of the bat in baseball is a gorgeous sound. But you don't quite get the full effect unless you're very close to the field, because the roar of the crowd often gets to you before the crack of the bat does. In golf, there is all that delicious silence, so the sound of a top pro hitting the ball is so pure. The feeling the pro gets—that sweet sensation that goes through the hands, up the arms and into the heart—the sound gives the fans a taste of that.

LEE TREVINO made a spectacular hole-in-one on the 17th hole at PGA West in 1987. Back at the Skins Game a year later, I was playing with Lee in a practice round. The flagstick was on the other side of the green. Lee took the same club—a 6-iron, as I recall—and hit the shot almost exactly where he made the ace. He looked at me, held the club up and said, "You know, Vinny, this club has the greatest memory."

BESIDES HIS Hall of Fame golf ability, Lee was blessed with a couple of other things. One was great teeth. Perfect; never had a cavity. I envied them because I've always had Irish teeth. In fact, if I were to write my autobiography—which I will never do, by the way—I would title it, My Life in Dentistry.

I HAVE A PICTURE in my mind of Payne Stewart coming down the stretch at Bay Hill in 1987 and venturing off the course to his home along the 12th hole. And picking up his young daughter and giving her a kiss. Maybe it's because I'm a family man, but that's the single image in golf that has stayed with me more than any other.

AH, THAT 1975 Masters. When Tom Weiskopf and Johnny Miller had putts on the last hole to tie Jack Nicklaus, I said at the time, "So it comes down to this..." and briefly outlined the scene as clearly as I could. At that point, I swiveled the microphone on my headset over my head, away from my mouth. I did that so I could resist the announcer's temptation to say something else. There really is nothing to say at that point. The silence as Tom and Johnny prepared to putt was profound. Thousands of people encircled 18, yet I could hear birds chirping in the trees. Not a sound from the patrons, and it was that silence that was the star. It conveyed all the tension, expectance and suspense. To me, there is nothing more magical in golf than the nothing sound of silence.

ON THE OTHER hand, silence isn't always golden. I do love the roar of the crowd, and have since I was a little boy, and would crawl under the giant radio in our living room and listen to college football games. When Hank Aaron hit the ball for his 715th home run, in Atlanta in 1974, I said, "It's gone" and nothing else. The roar literally was deafening, and I had the good sense to again remove my headset and place it on the counter. I got up and walked to the back of the booth and cooled my heels. The wait allowed me to calm down so that when I came back on—I stayed away for a minute and 40 seconds, an eternity—I'd gathered my thoughts and could say something intelligible. So when I came back on I said something to the effect of, "A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol." I added quite a bit more, but the hero of that broadcast was the roar of the crowd.

Vin Scully and Lee Trevino working in the NBC golf broadcast booth in the 1980s.

PGA TOUR Archive

MY KIRK GIBSON home-run call [1988 World Series] is brought up to me quite often, and my answer is, sometimes God helps you through these things. I honestly believe that, because before he blasted the ball into the right-field bleachers I had no inkling I would say, "In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened!" It just spilled out of me, and it was a good line, but it was God's line, really, not mine.

I'M A BIG READER. I buy a lot of books, but I get a lot of books sent to me. They accumulate like you wouldn't believe. When we moved from the Palisades to Hidden Hills, I donated close to 400 books to a local library. I do enjoying reading a lot. For a realistic view of baseball at the major-league level, get Three Nights in August by Buzz Bissinger. If you want to know how sports can impact a man and his family for better and worse, get When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi by David Maraniss. If you want a highly entertaining, funny golf novel, get Dead Solid Perfect by Dan Jenkins.

ROBERT REDFORD wears a solid-color necktie because attention naturally will be drawn to his face. As you can see, I often wear striped ties. Here's the handkerchief in my pocket, and here's my watch. I'm not Robert Redford. With my face, I need all the distractions I can provide.

WHEN I WAS about 15, I heard about a job opening in "the silver room" at the Hotel Pennsylvania in Manhattan. The name sounded almost romantic. I jumped at it. Well, the silver room was not much more than a walk-in closet down in the bowels of the hotel. Down a chute came every dirty piece of silver in the hotel. Coffee creamers, silverware, serving bowls, you name it. You put the silver in a wire basket and placed it in the "tabernacle," a device with canvas curtains around it. You pulled a wooden lever, and scalding hot water would come down on the silver and clean everything off it. When the cleaning was finished, you reached in with your heavy gloves and pulled out the baskets. Steam and the smell of decaying food would pour out. Twice a day, I would pass out from this. I would wake up in a small hallway where my partner would drag me. To this day, mention of the word "silver" brings on a slight wave of nausea. Through the years, when there was a tough road trip or a long doubleheader, I'd think of the silver room. And how, all things considered, my gig wasn't so bad.

SINGLES HITTERS drive Fords; home-run hitters drive Cadillacs. It will always be so. The long ball is the big thing, not just in baseball but golf as well. The appeal of measuring things—the distance a golf ball flies, tape-measure home runs and the speed of a fastball, are eternal. At Dodger games, they flash on the scoreboard the speed of the last pitch as shot by the most recent incarnation of the radar gun.

TONY GWYNN, one of the best hitters in the history of baseball, says there's no way the radar guns are accurate. I happen to like the speed going up there because it's great theater. But between you, me, Tony Gwynn and many experts, the radar gun is off.