Drawings From Prison

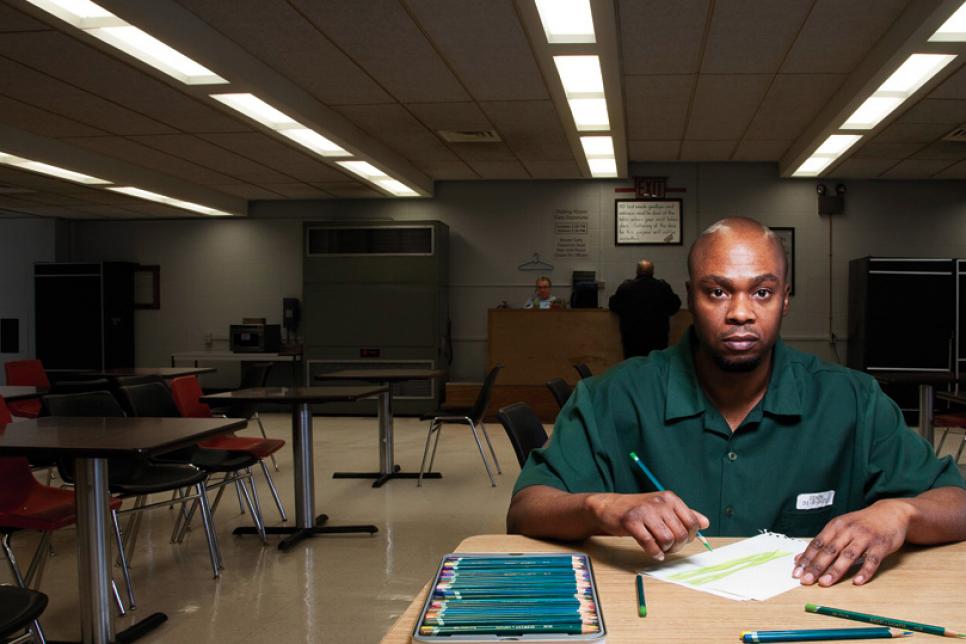

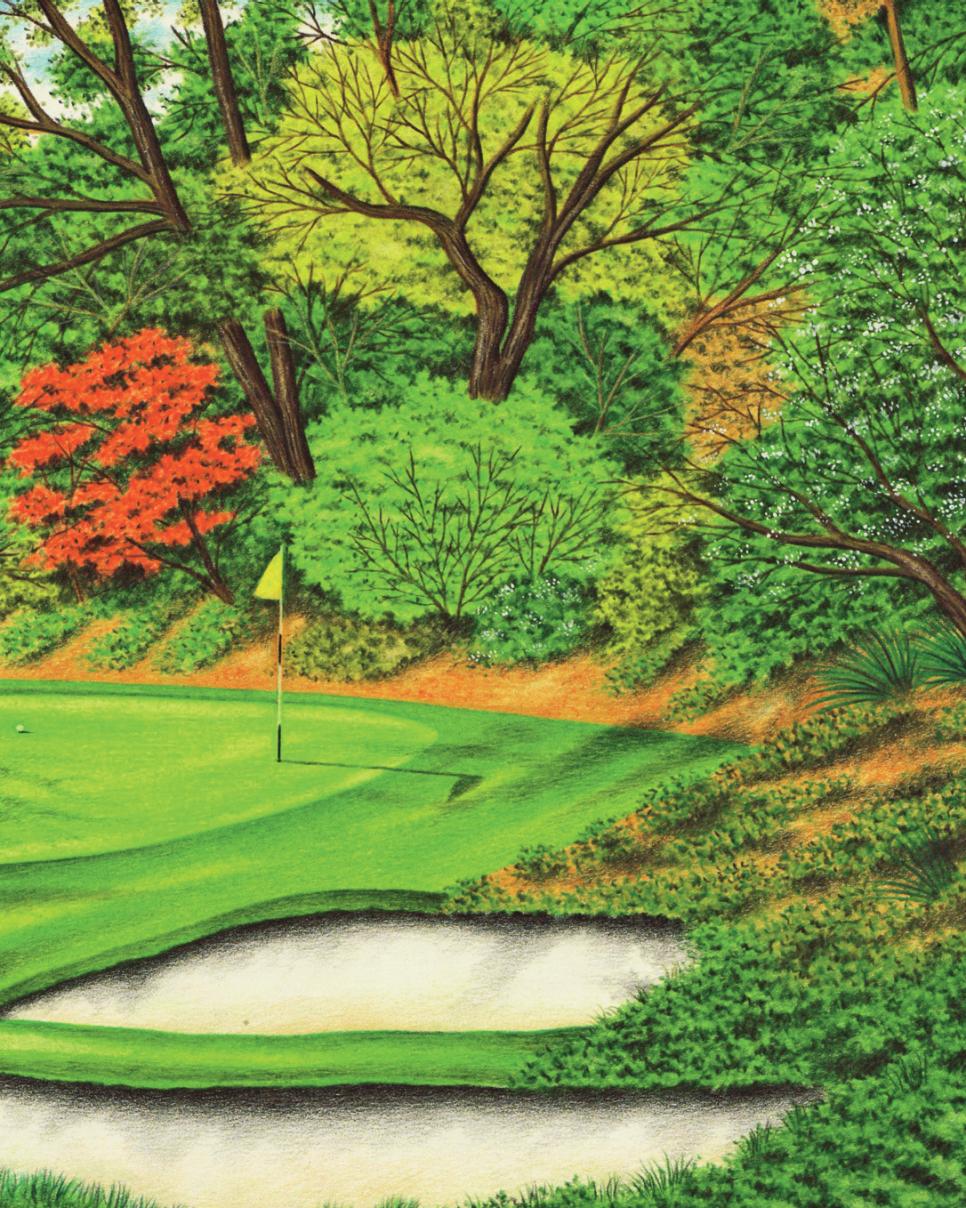

I've never hit a golf ball. I've never set foot on a golf course. Everything I draw is from inside a 6-by-10 prison cell. The first course I ever drew was for warden James Conway. He would often stop by my cell to ask how my appeal was going and to see my drawings. Before he retired, the warden brought me a photograph of the 12th hole at Augusta National and asked if I could draw it for him.

I spent 15 hours on it. The warden loved it, and it was gratifying to know my art would hang in his house. Something about the grass and sky was rejuvenating. I'd been getting bored with drawing animals and people and whatever I'd get out of National Geographic. After 19 years in Attica (N.Y.) Correctional Facility, the look of a golf hole spoke to me. It seemed peaceful. I imagine playing it would be a lot like fishing.

There's an inmate here who subscribes to Golf Digest. He crosses his name out and loans me the issues, because you get a ticket if you're caught with something that has somebody else's name on it, just like you get tickets for draping sheets across your bars, or fighting. Some guys in here break the rules anyway, but life's better when you stay invisible.

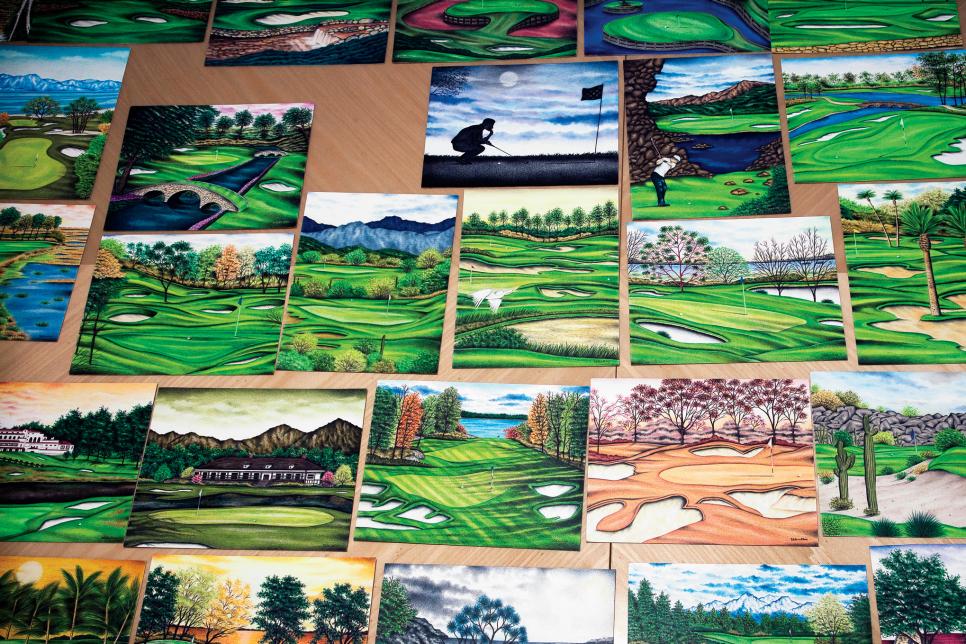

Except for that one drawing for the warden, I never copy holes exactly. I use a photograph as a starting point and then morph the image in my own way. Sometimes I'll find a tiny piece of reference material, like a tree on a stamp or mountains on a calendar, and then imagine my own golf course with it. I find the challenge of integrating these visions very rewarding.

The past two years I've drawn more than 130 golf pictures with colored pencils and 6-by-8-inch sheets of paper I order through the mail. We're not allowed to have brushes and paints, but that's all right; I like pencils. When I was little, my mom and grandma used to slap my hand because of the unconventional way I gripped the pencil, until one day my aunt Gwen told them to stop and look at the comics I'd done from the newspaper. My mom didn't believe I'd done it without tracing, so she made me draw them again freehand as she watched.

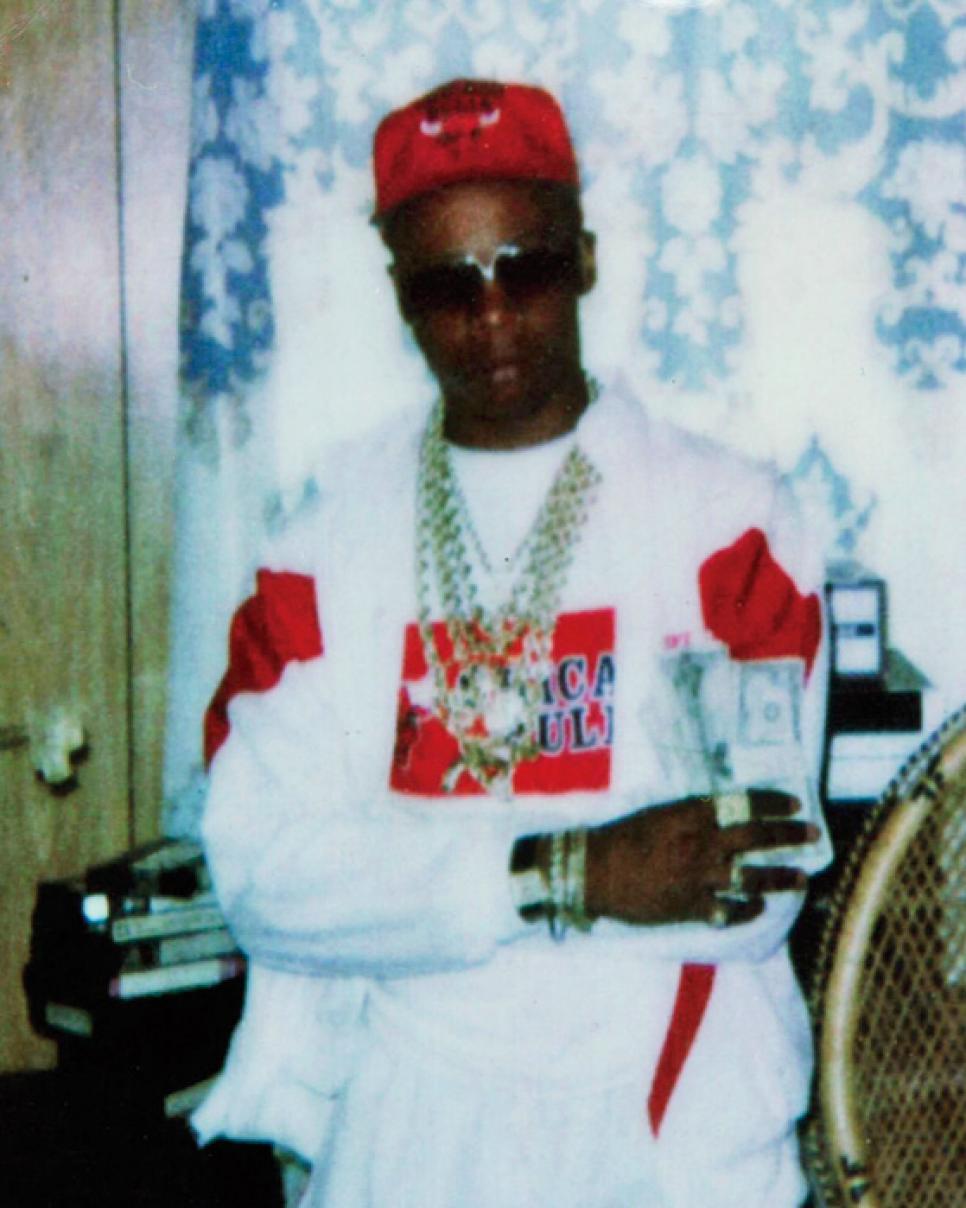

Growing up on the east side of Buffalo, my only sports were football and basketball. Talk about golf in our neighborhood and you'd probably get shot. Because of my art ability, I attended the performing-arts high school and stayed pretty clean until I graduated. Then I started dating a girl whose brothers were drug dealers, and before long I was in it, too. It's no excuse. It was what you did in my neighborhood if you wanted to make money. I became a mid-level cocaine dealer and pulled in enough to drive flashy cars and cover friends, but not much else. I rode with a weapon, same as everybody. I was out on bail for possession charges the night my life changed forever. I was 21 then. I'm 42 now.

No one likes to hear how you're innocent. I get that, and I don't talk about my case to inmates or guards. Everyone's innocent, right? Truth is, there are a lot of bad folk in Attica who deserve to be locked up. They were animals even before they were treated as animals. Violent people who want to rape and cut you, and society is safer because they're in here. But there are also people who'd never hurt anybody, who deserve a second chance. And out of 2,200 inmates, you'd better believe there are a few innocents who got railroaded by the system. When you're young and black, it can happen, and it happened to me.

It was 1:30 in the morning, and we were hanging out at a popular street corner. There were probably 70 people there when word came that the Jackson brothers were looking to get my friend Mario. It was over a girl. You never knew how seriously to take these threats in our neighborhood, but sure enough, I was in a store buying beer when I heard the shots: pow pow. I ran outside the store and grabbed my half-brother to flee. I didn't want any involvement. I was out on bail, and of all things, I wasn't going to let some romance drama among younger kids land me in prison.

I drove home and went to bed. From what I saw, I didn't think anybody had died. The next day the cops pulled me over, and within minutes a tow truck was there to haul away my car. It wasn't until I got to the station that they said I was being charged with second-degree murder, second-degree attempted murder and third-degree assault.

I wasn't nervous because so many people had witnessed the shooting. But soon there I was, being paraded before television cameras in a white paper suit on my way to county lockup. Two days later, LaMarr Scott, a guy I knew but wasn't close to, gave a statement to WGRZ television confessing to be the shooter and turned himself in to the police. Because my dad drove LaMarr downtown, much was made that he had coerced LaMarr into confessing. For murder? Please. My half-brother had brought LaMarr to our dad to set everything straight, and LaMarr owned only a bicycle.

I now see LaMarr regularly. One year after I was convicted, LaMarr shot a teenager in the face after an armed robbery and made him a quadriplegic. I choose not to hold a grudge against LaMarr because psychologically, it would kill my spirit. LaMarr's eligible for parole in 2018; I'm not up until 2030.

For the past 12 years I've lived in "honor block," which holds 145 inmates with the cleanest disciplinary records. We can shower every day, use the telephone, and our cells are mostly open so we can socialize and play cards and chess. There are hotplates we share to cook our food, and I buy a lot of rice, beans and pack-dried chicken from the commissary. Still, tension can brew in here. A guy will tell another guy to take it to the back, but mostly people want to stay here so they avoid trouble.

Every two months I get to visit my family for two days in a trailer. My mom lives an hour away, and I have three daughters (my youngest can thank her existence to the family-reunion program) and a wife, Louise, who was recently deported to her native Australia. Louise encountered my drawings on the Internet and moved to the United States to help with my appeals. We were married in a brief ceremony in the visitation room.

The light in my cell isn't great for drawing, but I do have an outlet to plug in my Walkman. When I draw I listen to cassettes to block out the noise of the other prisoners, which can get relentless, even in honor block. I also work as a barber, do push-ups, run in place and read. One of my favorites is Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl about his experiences in a concentration camp. You have to find meaning in your suffering, Frankl said. To that, I say I think God put me here to draw golf courses. Maybe one day I'll play.

Some days I feel like giving up, it's true. I just want to turn nasty and bitter, but in a few hours, or maybe a few days, I'm reaching for the pencils again.

It's possible I wouldn't have lived to this age if I'd stayed on the outside. When I was a young man I wasn't useful to society -- this I don't argue. But I'm not a murderer. That's the worst thing somebody can be, and I'm not that. I hope all you need to do is look at my drawings to know that.

IS VALENTINO DIXON INNOCENT?

It might be impossible to know exactly what happened in a beery east Buffalo parking lot on the early morning of Aug. 10, 1991, but it's worth trying to figure out: Someone's freedom is at stake.

As many as 70 people were present when what started as a fistfight ended with gunfire. Four young black males were shot, and one, Torriano Jackson, was killed.

Valentino Dixon is at Attica (N.Y.) Correctional Facility, having served 21 years of a life sentence, and still protests his innocence. Another Attica inmate, LaMarr Scott, has confessed to being the killer, but his words are not taken seriously.

It's an extremely complex case. Across two decades, 15 eyewitnesses have testified in court or signed sworn statements. These witnesses pretty much shake out 7 to 3 in favor of Valentino Dixon's innocence, with the others saying everything happened too fast or their vantage wasn't clear. Nearly everyone there was a teenager, and many of the key participants didn't know, barely knew, just met, or claimed not to know other key participants.

Clearly, some are telling the truth and some are not. Depending on how you mix, accept or deny the conflicting accounts, two versions emerge: (1) Known drug dealer Valentino Dixon, 21, stood over Torriano Jackson, 17, and emptied the clip of a 9-millimeter automatic. (2) LaMarr Scott, 18, struggled with the same automatic, and when he finally got the barrel under control, he settled its aim on Torriano Jackson, who had shot first.

Minutes before the 1:30 a.m. shooting, a yellow Geo Storm pulled up and parked at the corner of Bailey and East Delavan avenues. From this car emerged Torriano Jackson and his older brother Aaron Jackson, 20, intent on confronting Mario Jarmon, 19, over an earlier dispute. They exchanged angry words. A crowd circled. Then, at the sound of gunshots, the crowd dispersed.

The police arrived shortly. From the bloody pavement officers recovered a .32-caliber handgun with a single spent bullet in its cylinder, a .22-caliber bullet casing, and 27 spent 9-millimeter bullet casings -- same as what riddled Torriano Jackson. (This is significant because the prosecution would present Valentino Dixon as responsible for shooting all four people.) The murder weapon was never recovered.

Christopher J. Belling, who prosecuted the case and is now the senior trial counsel of the Erie County District Attorney's Office, says the extra gun and bullet casings don't cause him to doubt that Dixon was the only gunman responsible. "Given the neighborhood and the chaos of the scene, they could've come from anywhere," Belling told Golf Digest in April 2012. "Whoever had the .32 probably decided they didn't want to have it in their hand anymore. They wanted it on the ground."

As the wounded were taken to hospitals, the police interviewed people who lingered at the scene. Some of these records haven't survived, but the police did speak to the driver of the yellow Geo, Travis Powell, 22, who said he didn't recognize the shooter.

Emil Adams, 18, made a sworn statement at the police station. He described two guys with guns; he knew neither. He said the smaller guy had a handgun and the "heavyset" guy had the automatic. That afternoon, Valentino Dixon, 5-foot-9 and 145 pounds, was arrested. His car and clothes were confiscated so they could be tested for gunpowder residue and blood.

John Sullivan, 17, who'd been released from the hospital that morning after being treated for a gunshot wound to the leg, signed a statement with police 45 minutes after Dixon's arrest. He didn't see who'd shot him in the leg, but he named Valentino Dixon as the individual who killed Torriano Jackson.

The next day the police visited Mario Jarmon (the person the Jackson brothers had been intent on fighting) in the hospital. In addition to being punched and kicked, Jarmon had been shot and couldn't speak because of a tracheal tube. The police report states: "He nodded his head to indicate that the guy that shot him was the dead guy. . . . [He] did not see [Valentino Dixon] with a gun."

Two days after the shooting, the police visited Aaron Jackson in the hospital. (The brother of the deceased would spend weeks recovering from his bullet wound.) The detective showed Jackson six mugshots, and Jackson picked No. 4. The identity of No. 4 is absent from the detective's one-page report. Written on the bottom of the report is Jackson's quote: "But I can't be sure, it all happened so fast."

That same night, LaMarr Scott confessed to a local TV reporter that he, not Valentino Dixon, had shot Torriano Jackson. According to Scott, the guys in the yellow Geo had made threats throughout the day, which prompted him to ride his bike home and retrieve his 9-millimeter, a gun he had recently bought with cash but hadn't yet fired. When the argument escalated at the parking lot, Scott said Torriano Jackson shot first. "I was scared," Scott told the TV reporter. "I didn't know whether he was gonna kill anybody or not, so I just opened fire back on him. I didn't have any control of the automatic weapon at all, and I panicked at the same time. That's why I kept shooting him as many times as I shot him."

But this apparent good news for Valentino Dixon didn't last long. After meeting with the police and Belling, LaMarr Scott recanted what he'd told the TV reporter (and said Dixon's family put him up to the confession) and was not held or charged.

Dixon remained in prison the rest of the year. Mario Jarmon recovered, and in January 1992 a grand jury investigated the shooting. In this hearing, Mario Jarmon and another eyewitness, Leonard Brown, 20, corroborated the story of LaMarr Scott shooting an armed Torriano Jackson. Belling charged them both with perjury. At this same hearing, LaMarr Scott testified, "[Torriano] pulled out a gun and shot Mario three times and then Valentino shot [Torriano]." Concerning Valentino Dixon's gun, Scott testified, "I guess he had it. I didn't see the gun with him at the time when we walked to the corner because we was all laughing and giggling and everything. I wasn't paying attention."

In June 1992, 10 months after the fight, the murder trial began. Because Jarmon and Brown had been charged with perjury, they were not called as witnesses. "Even if I tried calling them to testify, their attorneys wouldn't have let them because it would've exposed them to additional perjury liability," Joseph Terranova, Valentino Dixon's court-appointed public defender, told Golf Digest in May 2012. "What Belling did was extremely clever, and the right thing to do as a prosecutor."

"That sort of witness intimidation by the prosecution almost never happens," says attorney Don Thompson, who worked for a number of years on Dixon's appeal but is no longer involved. "If you're just engaged in a search for the truth, you let the jury have everything and let them sort it out. On the other hand, if you've already decided what the truth is, you try to eliminate any testimony you don't like that isn't consistent with your version." Thompson also believes the perjury indictment might have deterred other witnesses from coming forward.

As for why he indicted Jarmon and Brown for perjury, Belling told Golf Digest in February 2012: "A lot of prosecutors would call it a brilliant stroke of tactical genius." Belling says Brown (Dixon's half-brother) and Jarmon (Dixon's friend) both lied to cover for Dixon, who had accidentally shot Jarmon with a stray round.

Of the prosecution's six witnesses, three testified they saw Dixon firing a gun. Of the three, Aaron Jackson gave the most vivid account. He was there with his little brother, Torriano Jackson, punching and kicking Jarmon, when he heard shots and felt shells brush his body. Shot in the stomach, he crawled to the yellow Geo with the thought of starting it and running over the shooter. He said he then turned to see Dixon kill his brother.

On cross-examination, Jackson was asked to reconcile his current certainty with his statement at the hospital 10 months earlier. Jackson responded, "My memory gets better with time." When questioned why he didn't volunteer Dixon's name (a man he knew) at the hospital, he said, "I don't remember," citing emotional and medical stress.

Emil Adams testified he jumped behind a car when he heard gunshots. Consistent with what he'd told police hours after the shooting, he testified he saw two men walk up to the fight, each carrying guns. But unlike before, at trial Adams could give a description of only one: Dixon. In his police statement Adams had said, The "kind of skinny" guy had a handgun, and the "heavyset" guy had the automatic. At trial Dixon was asked to stand, and Adams agreed the defendant was not heavyset. LaMarr Scott, who is now 6-foot-2, 270 pounds, weighed 200 pounds when he was 18.

There is controversy over the alleged interaction Emil Adams had with private investigator Roger Putnam in 2000. Working on behalf of Dixon's appeal team, Putnam says he visited Adams several times at a barbershop where Adams worked. Putnam said in an affidavit that Emil Adams indicated that his trial testimony had not been truthful and agreed to meet at Putnam's office to record a statement, but he never showed. (Adams has since sworn to police, "I do not know a Roger Putnam. I never talked to Putnam. I never lied in court or was coerced by the District Attorney's Office.")

Bob Lonski is the administrator of the Erie County Bar Association Assigned Counsel Program, which gives public defense to people who cannot afford to retain counsel in criminal matters. In the 18 years Lonski has worked there, Roger Putnam has been a regular investigator for their attorneys. Says Lonski of Putnam: "I've never heard a single mark against his reputation. While some investigators are known as computer sleuths, he's known as a very experienced guy who has a lot of contacts on the streets."

Prosecution Witness No. 3, John Sullivan, had a charge pending in Georgia when he was escorted to Buffalo under custody to testify. (He was convicted of sexual battery and simple assault.) Shot in the leg during the fight, Sullivan had fled to the steps of a church 86 yards away (as later measured) when he saw the killing. Sullivan admitted to smoking marijuana sprinkled with cocaine and drinking malt liquor earlier in the day, but he said he slept off the high and wasn't hindered by distance or the quality of the streetlights in identifying Dixon.

Jospeh Terranova, Dixon's public defender, waived the opportunity to make an opening statement and called no witnesses. With Jarmon and Brown neutralized by perjury charges, "The witnesses we had left were not that strong," said Terranova after the trial. "If I'd called one or two weak witnesses, the jurors might have asked themselves: Is that all the defense has to offer? He must have done it."

The first pages of the trial transcript detail Terranova relaying his client's request for an attorney other than himself. Valentino Dixon claimed Terranova had visited him only once in jail, was unprepared because there were witnesses he hadn't talked to, and was possibly aligned with the prosecution. Terranova says he was prepared. "When you're appointed by the court, it's not unusual that the client has a certain level of frustration and feeling of powerlessness. It's not unusual that they lash out at the only people capable of helping them."

In the trial, Terranova tried to impeach the credibility of the prosecution witnesses. He stressed the absence of motive and rested on the fact there was no physical evidence linking Dixon to the victim, Torriano Jackson. The murder weapon was never recovered, and the test results of Dixon's clothes and car had produced nothing to submit.

Carl Krahling, now 53, was the foreman and youngest member of the all-white jury that convicted Dixon of second-degree murder, second-degree attempted murder and third-degree assault. To this day Krahling remains unsettled. "The first vote was 9-3, not guilty, and I was one of those [voting not guilty]," he says. As he remembers, one very vocal juror steadily persuaded the rest over 14 hours. But his most vivid memory is of their 11 p.m. police escort through the chaotic courtroom after the verdict, news cameras flashing and Dixon's mother wailing. On the way out, Krahling says, the judge called him into his chambers and asked, "What took so long?"

Two decades later, Krahling's memory of what the judge said is this: "There's a lot you're not allowed to know. Just trust me, you did the right thing on this. The guy lied to the grand jury; he was involved with weapons charges and drive-by shootings, drug dealings. This guy is a menace and should be off the street. Sleep well tonight, you did the right thing."

Judge Michael D'Amico says his recollection of the case is faint, but he is certain this never happened. "In the first place, I don't usually talk to individual jurors, and, secondly, I would never say something like that."

"In retrospect I should've hung the jury," Krahling told Golf Digest. "All the people testifying seemed like shady characters. And if they were all members of a rival gang, who knows what happened?"

Three months after Dixon was sentenced, Jarmon and Brown faced their perjury trial. A key line in the prosecution's opening remarks reads, "The proof in this case is going to show that only one person had a gun that night. That was Valentino Dixon."

Jarmon and Brown were acquitted of three of four counts of perjury. In essence, the verdict decreed the two were not lying in saying Torriano Jackson had a gun, shot it, and shot it at Mario Jarmon. But the verdict says they were lying in saying LaMarr Scott was the person who shot back.

Judge D'Amico presided over Jarmon and Brown's perjury trial as well as Valentino Dixon's murder trial.

LaMarr Scott entered Attica on the heels of Valentino Dixon. He is serving 25 to 50 years for a 1993 shooting after an armed robbery that left his victim a quadriplegic. He has reverted to the original story he told the TV reporter, that he killed Torriano Jackson. Scott told Golf Digest in March 2012, "Each and every day it eats away at me that I allowed them to convince me to do the wrong thing." He's eligible for parole in 2018, so he risks more prison time if the responsibility for Torriano Jackson's murder is switched to him.

As a reward for a clean disciplinary record, LaMarr Scott is also one of the 7 percent of Attica inmates who live in "honor block." He encounters Valentino Dixon regularly, and both say their relationship is cordial. "You can't think negative in here," Dixon says. "The more you resent your situation, the quicker you're going to start dying."

LaMarr Scott says criminal justice personnel pressured him into changing his story by bringing his foster parents into the meeting room and threatening their well-being after they left. The earliest record of Scott re-confessing is a 1994 interview he had with Dixon's attorney. Again in 2002, Scott took responsibility for Torriano Jackson's death in a sworn statement, but this generated nothing of consequence. On confessing to police detectives two days after the shooting, Scott wrote in his 2002 statement, "I was told that they had who they wanted, and to leave the situation up to them."

"No, it didn't happen," Christopher Belling says about pressuring Scott. "[Scott] had his own lawyer, and I don't remember any foster parents being there. . . . [Scott] came to the grand jury, and he told a different story. That was the story the grand jury heard, and that's the story they went with."

Valentino Dixon's theory of the case -- and his conviction -- hasn't wavered. He believes criminal-justice personnel saw an opportunity to halt the ostentatious and rising criminality of his cocaine dealing, and seized it. He says he didn't have a gun that night. He believes the prosecution used Sullivan's pending charge as leverage to get him to testify a certain way. The night of the shooting Dixon had been out on bail for 10 months. When he heard shots, he says, he got out of there as fast as he could.

Belling says that any criminal charges Sullivan faced had no connection or impact on Dixon's case. "Apples and oranges," says Belling.

Besides dealing drugs, Dixon's worst mistake might have been cutting ties with distinguished attorney Don Thompson. "Appeal work goes very slowly. I understood his frustration, but it was a frustrating case for us, too," Thompson says. "Probably for good reasons of their own, the witnesses we were trying to track down didn't want to talk or be found."

Of the handful of witnesses who have surfaced since the murder trial, the most compelling might be Tamara Frida, a social worker with a master's degree who was working in a lab at Buffalo General Hospital in 1991. She says she clearly saw LaMarr Scott shoot Torriano Jackson before she scrambled behind her car. That night a bullet punctured the radiator of her red Geo Tracker, and on the drive home it broke down. Fear of gangland retribution, she says, is what kept her quiet until 1998.

"[Torriano] fell face down in the street, and LaMarr was behind him, shooting. They were headed right toward my car. It all happened maybe 10 yards away," Frida told Golf Digest in March 2012.

A Buffalo police intra-departmental memo dated four days after the shooting documents a phone call from a female who refused to identify herself: "She said Valentino was not the shooter. . . .She was asked if she was the girl from the red Tracker, and she said yes. . . . She would not say if she could identify the shooter. . . . She would think about it and call back later."

Tamara Frida says she was the one who made this phone call, but out of fear she didn't call back.

There have been wrongful convictions in Erie County. In 2008, prosecutors dropped murder charges against Lynn DeJac of Buffalo after 13 years served. In 2010, Anthony Capozzi of Buffalo was awarded $4.25 million for 22 years served for rapes he didn't commit. New DNA evidence overturned both convictions. Unfortunately for Dixon, the particulars of his case make the chance of new DNA evidence virtually nil. The only "scientific" backing Dixon has is the results of a lie-detector test he passed. The administrator of the test, Malcolm Plummer, 75, a career private investigator who now teaches criminal justice at Onondaga Community College, says he is convinced of Dixon's innocence.

As for appeals, Dixon has made three swings, all misses. The best explanation of why his conviction has been upheld is a 100-page report prepared by U.S. Magistrate Victor Bianchini in 2009. The report attempts to sort out which witnesses are telling the truth and which are not. On nearly every matter in dispute the report rules against the prisoner. The report says the statements of investigator Putnam (about Emil Adams) and Tamara Frida both lack "credibility." Magistrate Bianchini writes, "It is quite difficult to believe that [Frida] would stand by silently while Dixon, whom she purportedly knew to be an innocent man, was charged, convicted and imprisoned, based only upon her notion that she might be subject to retribution by persons unknown for reasons unknown." The only statement by LaMarr Scott "which appears to have any reliability, in this Court's opinion, is his sworn testimony before the grand jury, wherein he [said Dixon was the shooter]."

For Jarmon and Brown, the report cites their indictment on four counts of perjury and later conviction, yet omits that each was acquitted on three of the counts. The possible implications of this outcome are not addressed.

"The Magistrate erred in failing to hold a hearing [to hear new witnesses speak] on any issue in this complex case," wrote Jim Ostrowski in 2009, just one attorney who tried for Dixon. "Instead, he relied virtually verbatim on the highly dubious decision in the state court by Judge D'Amico... In the absence of a hearing where the credibility of witnesses could be judged, the Magistrate nevertheless made credibility judgments about witnesses."

Magistrate Bianchini declined to comment with Golf Digest, citing the ethical problem of a judge commenting on a case that is pending.

"A bureaucratic system is set up to protect itself, and so it's not in its interest to admit mistakes," says Ostrowski.

Serving a 39 years-to-life sentence, Dixon will be eligible for parole in 2030, when he is 60. But he maintains hope he will be freed before then. The Exoneration Initiative, an organization that provides free legal assistance to wrongfully convicted persons in New York, has looked into his case. Of all Dixon's dreams, his most vivid is to a draw a golf course from real life.