Consider the following 20-name roll call: Tom Weiskopf, Corey Pavin, Mark Calcavecchia, David Duval, Graham Marsh, Mike Souchak, Jug McSpaden, Johnny Revolta, Dutch Harrison, Jim Ferrier, Bill Mehlhorn, Doug Sanders, Johnny Farrell, Macdonald Smith, Max Faulkner, Bobby Cruickshank, Willie Macfarland, Hal Sutton, Susie Berning, Jan Stephenson, Sandra Palmer.

It’s a list, surely random to nongolfers, but also probably underwhelming to most golfers brought up in our current celebrity culture. Among the men, none won more than one major, and only Marsh (who had one PGA Tour victory but 45 more on assorted international tours) had more than the 24 official victories of the major-less Smith. But by definition, or at least my estimation, all are or were great golfers. And, very likely, in coming years most if not all will be inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Under the Hall’s new criteria established in 2014, all meet the eligibility requirements for induction. All are either deceased or least 50 years old, and have won either the minimum 15 official victories on one or, in combination, more of the world’s accredited tours (for the men: the PGA Tour, European Tour, Asian Tour, Japanese Tour, Australian Tour, Sunshine Tour; for the women: the LPGA, the Ladies European Tour, the Japan LPGA, the Korea LPGA and Australia Ladies Professional Golf), or have at least two victories among the majors (current or past) and/or the Players Championship.

To some hard-line golf historians, including some former players, the new criteria is too watered down and accommodating, so that golf’s pantheon has at best become a “Hall of Very Good.”

However, it’s a narrow-minded view. The practical reality is that golf, like any major sport, needs a vibrant Hall of Fame. The problem is that golf long ago ran out of truly iconic players to be enshrined. They all got in a long time ago, unfortunately in bunches. In 1974, the WGHOF's first induction class included 13 such icons: Patty Berg, Walter Hagen, Ben Hogan, Bobby Jones, Byron Nelson, Jack Nicklaus, Francis Ouimet, Arnold Palmer, Gary Player, Gene Sarazen, Sam Snead, Harry Vardon and Babe Zaharias. The next year, 11 greats of slightly lesser fame and accomplishment went in. Talk about blowing your savings account.

In comparison, baseball inducted only five players in the first Cooperstown class of 1936: Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Walter Johnson and Christy Mathewson.

Golf’s Hall also made a mistake in the last decade in inducting clearly destined players in their 40s—specifically Phil Mickelson, Ernie Els and Vijay Singh—in the interests of adding marquee value for the televised ceremony. But all three were simply too young to carry much gravitas. Lifting the minimum age of active players to 50 ensures the mistake will not be repeated with Tiger Woods, who turns that age in 2025, or for that matter, the now 46-year-old Jim Furyk. (Editor's note: The age minimum was reduced to 45 in 2020, and Tiger Woods will formally be inducted into the WGHOF in 2022.)

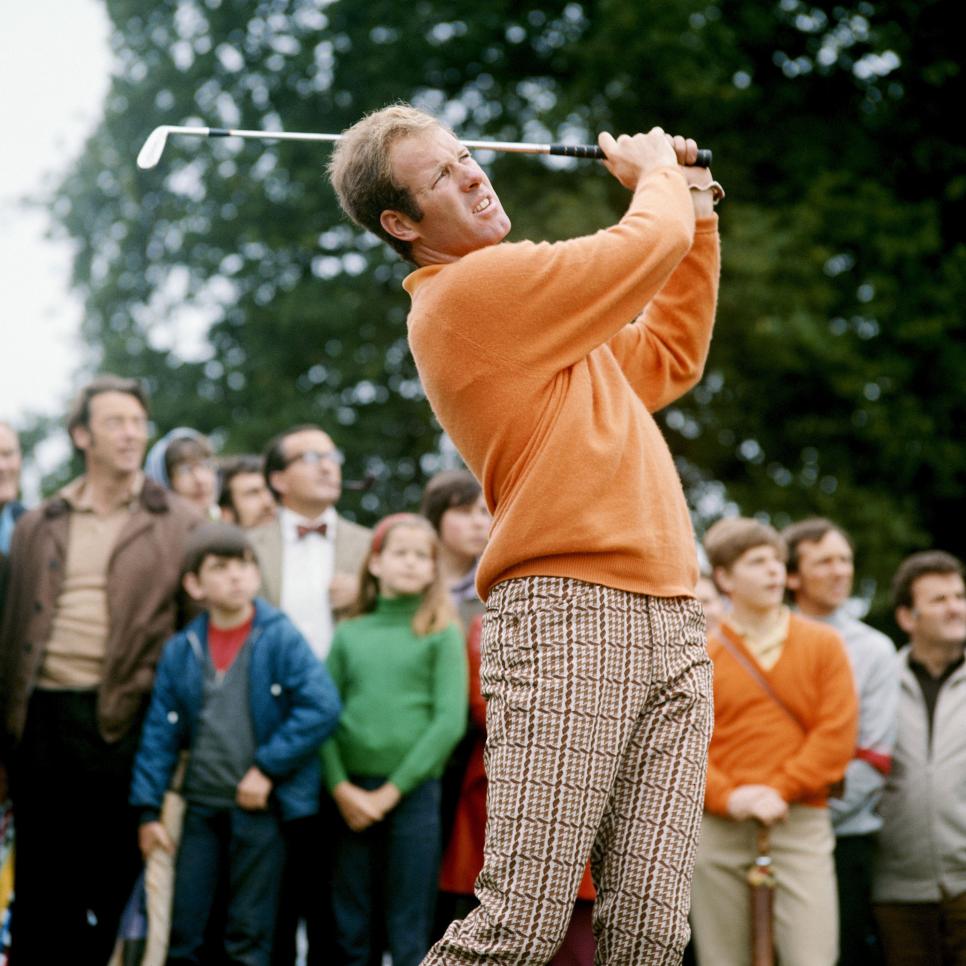

Peter Dazeley

Relatively speaking, the newest class, named last week and set for official induction in September 2017, has a lot of quality. Off his record, this year’s Davis Love III was likely most worthy, with 21 official PGA Tour wins including two Players Championships and a major, by a lot. Ian Woosnam, a former World No. 1 who won the Masters and 29 official tournaments in Europe, was the next best.

Golf’s Hall of Fame problem is that it’s a sport in which the only statistic that truly counts is winning (not consistently high finishes). Moreover, there are fewer past athletes than team sports, not to mention a relatively small pool of frequent winners to choose from. Indeed, as depth has presumably increased in professional golf, it is becoming more difficult to be a frequent winner.

The current leadership of the WGHOF to its credit recognized it had to slow down the rate of inductees. Now the ceremony is held every other year, honoring players and figures from four categories—male and female competitor, lifetime achievement, and veterans committee—with a maximum of five new members. This year, with Love and Woosnam, along with Meg Mallon, Lorena Ochoa (who, though only 34, had been retired the requisite five years) and the late commentator Henry Longhurst, hit the limit, with the selection committee choosing from a pool of 16 finalists. There were 145 inductees in the first 40 years of the Hall. Over the next 40 years, the number of newcomers can’t top 100, and will probably be significantly less.

There is no doubt the WGHOF has set minimum victory requirement that is lower than what had unofficially been imposed. But it had to. While 15 lifetime victories seemed like a pittance when the game’s giants—several with more than 60 victories and in some cases double-digit majors—were being inducted, it’s also become clear that winning 15 times in the post-1975 era is a greater achievement than it would have been before, much like a .280 lifetime batting average is now more worthy of a spot in Cooperstown.

Recognizing the greatness in players who were stalwarts but didn’t win as much as the very best helps one understand the immense challenge of the game. Lowering standards increases appreciation, and keeps up the supply of candidates. It’s all good.

Take for example Doug Sanders. OK, he didn’t have a major among his 20 victories (though he was second in majors four times). But not only was Sanders one of the great shotmakers of all time, he was a genuinely colorful and charismatic character who brought fans to the game. Consider, too, Tom Weiskopf. Yes, he underachieved with 16 victories including one major. But he was a truly majestic player, who in full flight, according to Gary Player, played the game at a higher level than even Nicklaus. And then there’s Corey Pavin. An undersized artist who found a way to employ amazing ball control to win a U.S. Open among his 20 official victories, even as golf was transitioning to the modern power game.

Philippe Le Tellier

The Hall’s veterans committee should not delay in voting in the late Calvin Peete (above), before Woods the greatest golfer of African-American descent in history, who with a completely self-made game won 12 times including a Players. The same thing for Paul Azinger, who contacted cancer in a prime during which he was America’s best player, but still won 14 times on the PGA and European tours, including a major.

The selection committee should be liberal in recognizing the game’s best players from modern eras, because achieving the minimum numbers is going to get harder. For example, Bubba Watson should go in on the strength of his two Masters and for being one of the most astounding shotmakers the game has ever seen. Three current European veterans—Lee Westwood (with 42 official worldwide victories but no major), Sergio Garcia (25 including a Players) and Henrik Stenson (an Open championship and a Players among his 15)—should get in even if they never hit another shot. And so should Retief Goosen, whose 34 official victories include two U.S. Open titles. (Editor's Note: Goosen was elected to the WGHOF Class of 2019.)

The WGHOF has gotten the right rate of flow. Now it just has to keep it steady. Giving more weight to international tours widens the pool of potential inductees and makes a statement that golf is a world game. It’s made important strides to be a respected, credible and edifying Hall of Fame, one whose leadership thoughtfully defines and justly applies a standard that recognizes the gradations of greatness, not just the absolutes.

Editor's Note: This story first appeared in the Oct. 24, 2016 issue of Golf World.