The conceded putt is a mystery to me. And I am more certain of this uncertainty after Sunday’s display of gamesmanship/poor sportsmanship by Suzann Pettersen at the Solheim Cup. What Pettersen did seemed on one hand so obviously wrong, so incongruent with golf’s very essence that the outrage might have been less if she flipped the bird at Juli Inkster or made the Gangsta Rap throat-slash gesture at Brittany Lincicome. (Privately, there are some who suggest golf could use some of this, that the game needs less garden party and more Fight Club. But I digress.)

The fact is the Solheim Cup controversy only exists because the conceded putt is such an inscrutable element of the modern game. Putting aside the most ridiculously obvious concessions (is there such a thing?), the gesture is more emotion than action, the grayest kind of gray in a game that is essentially only black and white.

On the one hand, I wonder if it is some vestigial tail reminder of our baser instincts, all vaguely couched in condescension or disgust. The thought bubble that surrounds every concession goes something like this: “Yeah, I’m giving this to you, but we both know that I don’t really think you’re good enough to make it if it really mattered. Moreover, I’m giving it to you because I’m better or holier or somehow more virtuous than you or any of your kind will ever be. And I need to remind you of that very fact at this very instant.”

Or worse, maybe the concession is just a grotesque form of strategy. Give short putts early, but make them putt those same putts when it’s late. It’s as if a cheap three-card monty con game was thrown in the middle of golf, the holiest cathedral of sport. Golf Digest’s instruction editor Peter Morrice reminded me that noted sports psychologist Dr. Richard Coop once suggested that early in a match, give the putt to your opponent when she leaves it short and make her putt it when she rolls it past. Subconsciously, she’ll think if it’s left short, she’ll be granted the next putt. Late in a tight match, she'll never reach the hole. Coop’s tactic seems at once as ingenious and laudable as it is a kind of cartoonish Simon Bar Sinister scurvy trick. How can conceding a putt be wrong and right at the same time?

And yet there’s the rub. The concession also seems imbued with a mythic grace, evidence of a certain spiritual nobility of golf’s better self -- and ours, as well. Other sports do not have this kind of ritualized acquiescence, this prescribed displays of honor. There are no conceded field goals in football, no gimme home runs or penalty kicks. Everywhere else in the vast panoply of sport -- from darts to drag racing -- is a fight to the death by any means necessary. By most appearances, golf stands on a higher plane. And this sense of moral high ground runs true whether you are in your 30s or your 70s. Young Golf Digest veterans Max Adler and not-as-young Bob Carney think of the given putt in similar ways.

Adler: “I've definitely played with golfers who give putts when it feels like the hole deserves to be halved; as in both players reached the green with the same quality of shots and it doesn't seem right that just because one lagged to one foot and the other to 30 inches that anyone should win.”

Carney: "I have come to think that gentility is a virtue and what the sport is about. Sounds corny, but expecting or hoping to win based on someone else's misplay is less satisfying and also engenders weakness in oneself. Err on the side of the gimme. Gimme when you'd want someone to do the same for you.”

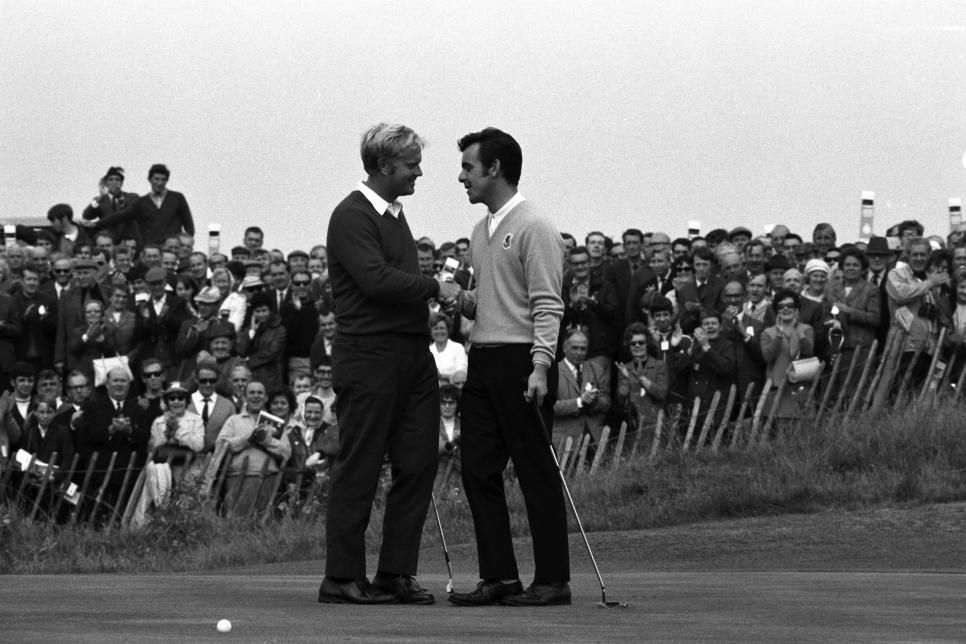

Of course, the most notable example of that kind of gentility writ large in golf’s history is Jack Nicklaus’s gesture at the 1969 Ryder Cup. Nicklaus conceded a putt of relatively inconsequential length to Tony Jacklin to end the 1969 matches in a draw. It was noble and ultimately immaterial in that the tied matches meant the U.S. retained the Cup, but it spoke volumes about Nicklaus’ class.

Or did it? Many still argue whether Nicklaus should have done it, and U.S. captain Sam Snead disagreed with it ‘til the day he died. It makes you wonder whether there ever is a right time to not concede a putt. The Pettersen incident turns the whole idea of conceding a putt on its head, leaving us further confused.

There are certainly plausible examples of times when not conceding a remaining tiddler seems more right than wrong. I and many on staff here offer just a few, some nefarious, others less so, almost all entirely justifiable. But to get you started:

But I’m not sure any of these suggestions make Sunday’s incident or the very practice of conceding putts or in this case not conceding them any more definitive. According to USGA Museum historians, Michael Trostel and Victoria Student, the idea of a conceded putt dates at least as far back as the 19th century.

But what is most telling to me is that the idea was accompanied by a very clear edict that held firm until the 1930s, which read: “The Rules of Golf Committee recommends that players should not concede putts to their opponents.”

And yet here we are. Whose path is more admirable then, that of Nicklaus or Pettersen? Or neither? One is clearly more despicable than the other, yet both remain rooted in uncertainty. And that doesn’t seem right. Golf is the most certain game I know. About as dead solid certain as a two-footer.