News

Special Report: What People In Golf Earn

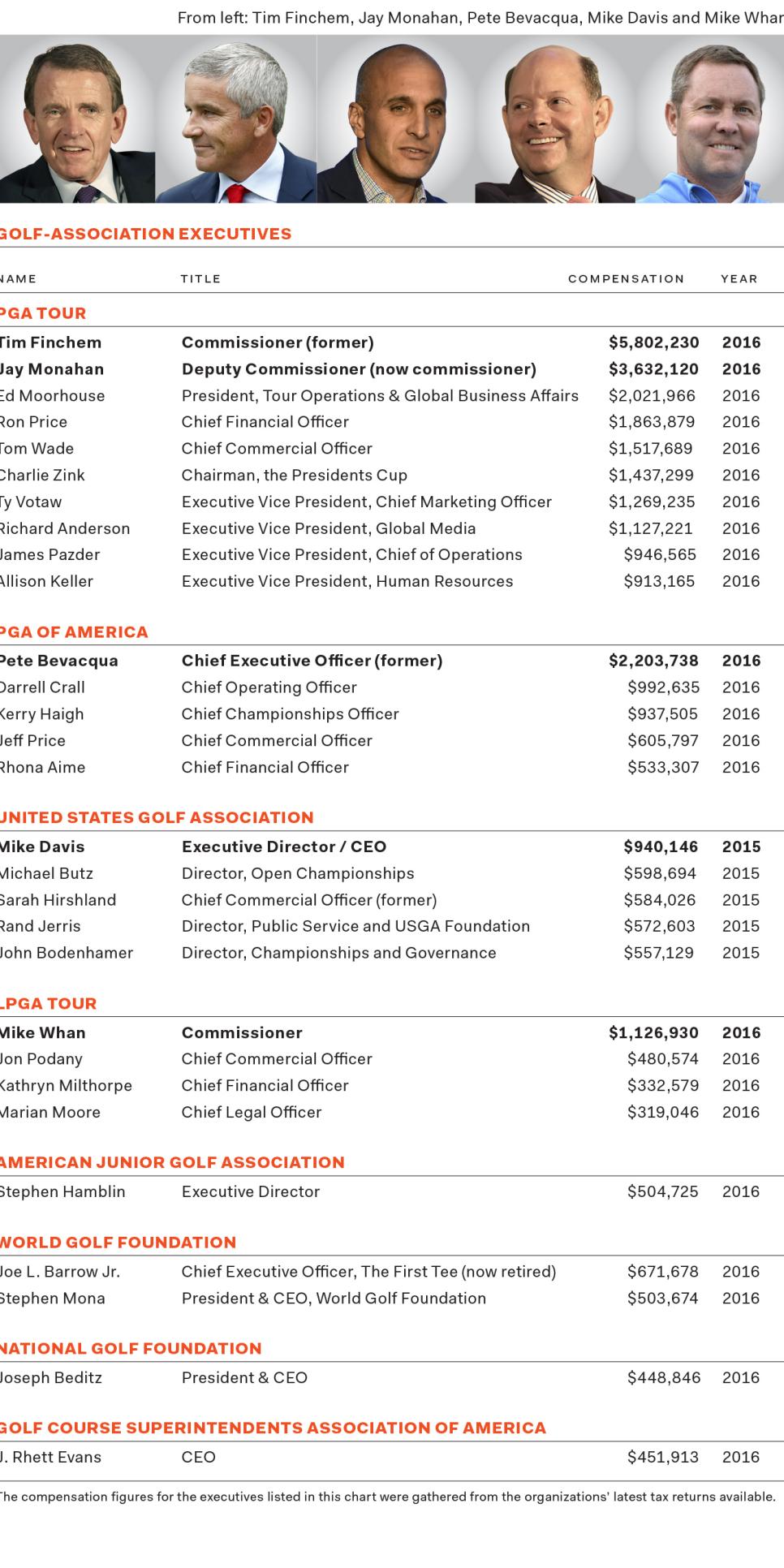

For many readers, the first thing that pops to mind when scanning the accompanying list of executive pay at golf's major associations will be the overall bigness of the bucks. Aren't these supposed to be nonprofits? The second thing might be the disparity between what the PGA Tour executives earn and the salaries of everybody else. Recently retired PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem's take-home pay was six times that of Mike Davis, the USGA's executive director. Given enough context, the numbers make sense, but you're still allowed to be a bit jealous.

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

One factor to remember is that nonprofits, even those founded by saints for saintly causes, must compete with the private sector, where compensation is supplemented by equity and stock options worth several times their base pay. Two executives on our list, for example, were hired away this summer. Pete Bevacqua, the PGA of America's chief executive, was lured to the private sector in July when NBC Sports Group offered him a newly created position. Bevacqua will oversee programming, marketing, digital, the group's regional networks and all of NBC's golf operations, including Golf Channel. Money probably wasn't the only reason Bevacqua decided to make the move, but one assumes he'll receive an increase over the $2,203,738 he was making at the PGA of America.

The other departee, also in July, was Sarah Hirshland, the USGA's chief commercial officer. She will stay in the nonprofit realm, but her new job as CEO of the United States Olympic Committee has a higher profile and an enticing challenge: rehabilitating the USOC's image in the wake of its recent sexual-abuse scandal.

All but the smallest nonprofits are required to report to the Internal Revenue Service how they determine pay rates for their officers, directors and key employees. Most large nonprofits impanel compensation committees, which in turn often hire outside consultants. A key criterion is the median salary for executives in similar nonprofits, lists of which are available via nonprofit-tracking organizations such as GuideStar and the Economic Research Institute. Significant deviations from the median, especially on the high side, raise red flags with the IRS and watchdog groups.

Determining which nonprofits are "most similar" to the major golf associations is more art than science, but nothing suggests that the top golf salaries are out of whack. The two highest-paid officers at the U.S. Tennis Association, for example, earned 39 percent and 9 percent more, respectively, than the $940,146 that the USGA's Davis earned. The $504,725 payday that American Junior Golf Association executive director Stephen Hamblin enjoyed in 2016 tallies quite closely with the $513,460 that Little League Baseball Inc. chief executive Stephen Keener earned.

Salaries for the top executives at other nonprofits on our list appear to be similarly in line with the norms. The National Golf Foundation, the World Golf Foundation and the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America can all be considered trade organizations created to support and/or lobby for their constituent members—golf businesses in the case of the NGF; the global golf industry and the world's major golf associations for the WGF; and golf-course superintendents in the case of the GCSAA. Comparable nonprofits such as the National Association of Realtors and the American Farm Bureau Federation pay their leaders similar salaries.

Managing organizations of this size isn't easy. The USGA, as an example, has 340 full-time employees and revenue of about $200 million. In addition to staging more than a dozen high-profile tournaments each year, the USGA operates a museum, runs an equipment-testing center, administers the rules of golf globally in coordination with the R&A, manages its computer-based handicap and course-rating system, and promotes sustainable golf-course management practices. Davis is in charge of all of that, and when things go south, he takes the heat, as happened this summer after overly harsh course conditions in the third round at the U.S. Open at Shinnecock created a furor. Davis had personally supervised the setup.

If Davis and his colleagues in golf's top nonprofit jobs deserve what they earn, why the big jump in pay for PGA Tour executives? Primarily because, practically speaking, the tour functions more like an entertainment business than a trade association.

PGA Tour Inc. qualifies as a nonprofit because it exists not to make money for itself or for owners and shareholders, of which there are none, but primarily to organize, support and create opportunities for its members, independent contractors that we commonly refer to as tour pros. (PGA Tour Inc. runs six tours around the world, including the PGA Tour Champions, the Web.com Tour and the PGA Tour Latinoamérica.) The difference between the tour and a standard trade association is that whereas realtors and farmers establish and run independent businesses, touring pros make money primarily by playing in tournaments that the PGA Tour organizes, sanctions and in some cases directly administers. In other words, the PGA Tour is a sports league, and as such has to play hardball in competition against other sports leagues and the entertainment industry in general. That requires executives capable of negotiating global television rights, signing big-ticket corporate sponsors to multiyear contracts, identifying local organizations to supervise the logistics of weekly tournaments attended by tens or hundreds of thousands of fans, perpetually ginning up interest in the professional game and massaging high-profile athletes' egos.

But compared with what rival sports commissioners earn, then-PGA Tour commissioner Finchem's 2016 salary of $5,802,230 is modest. (In January 2017, Finchem passed the commissioner's job to Jay Monahan.) NFL commissioner Roger Goodell's base annual pay is roughly $20 million, with incentives that in a good year can double his take-home total. NBA commissioner Adam Silver recently negotiated a contract extension through the 2023-'24 season. Financial terms were not disclosed, but his predecessor, David Stern, is said to have earned about $20 million a year. Even longtime NHL commissioner Gary Bettman reportedly earns nearly $4 million more than what Finchem, and now Monahan, makes. If Finchem were a tour player, his official earnings in 2016 would have ranked fourth on the money list, just ahead of Rory McIlroy. But he has little of McIlroy's and other celebrity players' off-course earnings potential.

The LPGA is also a sports league organized as a nonprofit, albeit on a smaller financial scale, which explains LPGA commissioner Mike Whan's proportionally smaller salary. The USGA and PGA of America also run tournaments, including their highly lucrative majors, the U.S. Open and the PGA Championship. But the primary mission of the USGA and PGA of America isn't to enhance the earning potential of the players who participate but to "promote and conserve the true spirit of the game of golf" (the USGA) and tend to the needs of club and teaching pros (the PGA of America). Profits from the U.S. Open and PGA Championship are redirected to those ends.

If you're looking for controversy, consider college sports, where top coaches and athletic directors sometimes earn multiples of the salaries of their university president. The market might well have things priced right there, too, but it could be the basis for an interesting discussion.

Photos: Finchem, Monahan, Davis: Sam Greenwood/Getty Images • Bevacqua: Hannah Foslien/Getty Images • Whan: Donald Miralle/Getty Images

John Paul Newport is a contributor to Golf Digest and the former longtime Wall Street Journal golf columnist.