News

How To Save Your Club

From the archive (October 1995): Good fellowship does not always rise to the surface. Sometimes it needs a good kick in the rear

Editor’s note: In celebration of Golf Digest's 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published. Catch up on earlier installments.

Michael M. Thomas is, as the British say, a well-clubbed golfer. Once a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, then a partner at Lehman Brothers, he knows his way around the founders’ rooms, locker rooms and “bird cages” of America’s elite golf clubs. He once won the club championship at the National Golf Links of America (1970) and knows how to make a Southsider. He’s written nine books, mostly Wall Street thrillers, and presided over the Midas Watch column of the Observer for a couple of decades. At 85 now, Thomas is the sagest of golf persons and the perfect voice to fix what’s wrong with private clubs today, just as he was 25 years ago when he proposed this piece to me and our former features editor Peter Andrews during a round at the National.

Recently I asked Michael if he recalled the origin of the idea, and he promptly responded with his Midas touch: “In 1995, I had a sense that the world of golf as I knew it might be changing with the appearance of two newly dominant powers. One was Tiger Woods—in that year he played in his first U.S. Open, at Shinnecock, and although he was forced by a wrist injury to withdraw after 24 holes, it was clear that he signified the arrival of a huge new super-superstar presence, and we all cheered. The second irresistible force was less welcome. Money had always been a part of the social and sporting conversation—but suddenly, it seemed, it could shout down every other voice. Mammon was on a rampage. Wall Street was blowing. An awful lot of new money was being made, and social life had been thoroughly transactionalized. Memberships in the “best” and most famous clubs became a kind of coin of the new realm. Corporatization was on the rise.

“This worried me. Clubs incarnate what Oscar Wilde said of natural ignorance: They are like ‘a delicate exotic fruit; touch it and the bloom is gone.’ They have a fine balance of qualities and objectives. They stand for something. They’re about right reason and civilized behavior. But they also confer a kind of identity, and there’s the rub.

“Clubs should belong to their members. If they are transformed into bucket-list destinations for gilded golf tourism, or utilitarian personal profit centers, something invaluable—something essential—is lost.

“Hence the piece I proposed to Golf Digest in October 1995. In the intervening quarter-century, the trend that made me nervous then seemed for a time to accelerate. Golf shops no longer concentrated on equipment; they came to resemble haberdasheries, stocked to the brim with expensive logo’d merchandise to be carried off by guests at corporate outings and sported at their home clubs.

“Fortunately, enough is generally enough. I feel the tide may be turning. Increasingly, I hear of clubs imposing quotas on unaccompanied guests, even on all guests. Tradition once again seems to matter: the past engaging in a lively dialogue with the present, later generations taking up the cause. Let us pray.” —Jerry Tarde

***

Money can buy almost anything, but there are three things it cannot buy: (1) a sense of humor, (2) a repeating golf swing and (3) the slightest idea of how to behave at a golf club. I’ve been studying millionaires and billionaires for close to 45 years, going back to when, barely a teenager, I used to keep breakfast-to-supper hours hanging around Joe Solis’ caddie shack at Cypress Point, absorbing existential lessons that have proved infinitely more helpful than anything I would learn at Exeter, Yale or Wall Street. Since then, I’ve reflected long and hard about the relationship between money and golf.

Golf is the preferred diversion of big new money. Where there has been a great financial boom, inevitably there will be a great golf boom. There are many reasons for this, but principal among them must be that no other sport offers as great a variety of opportunities to spend money on THINGS: on a set of titanium-headed clubs with super-graphite shafts on which as much technology has been lavished as on the Boeing 777; on a pigskin or alligator bag by Gucci or Hermès to tote the clubs around; on a jet by Gulfstream or Falcon to tote owner and bag around; on golfing couture in styles ranging from Lauren ’30s retro to Versace ’90s barfo.

At the top of the shopping list, however, is likely to be membership in a private golf club. It’s sad, but it’s a fact that, with the possible exception of polo, no pastime devised by man wears the modifier “exclusive” so easily as the ancient Scots’ game. In the clubhouse, the newest minted junk-bond mogul will find that he relishes above everything else what F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby calls “the consoling proximity of other millionaires.”

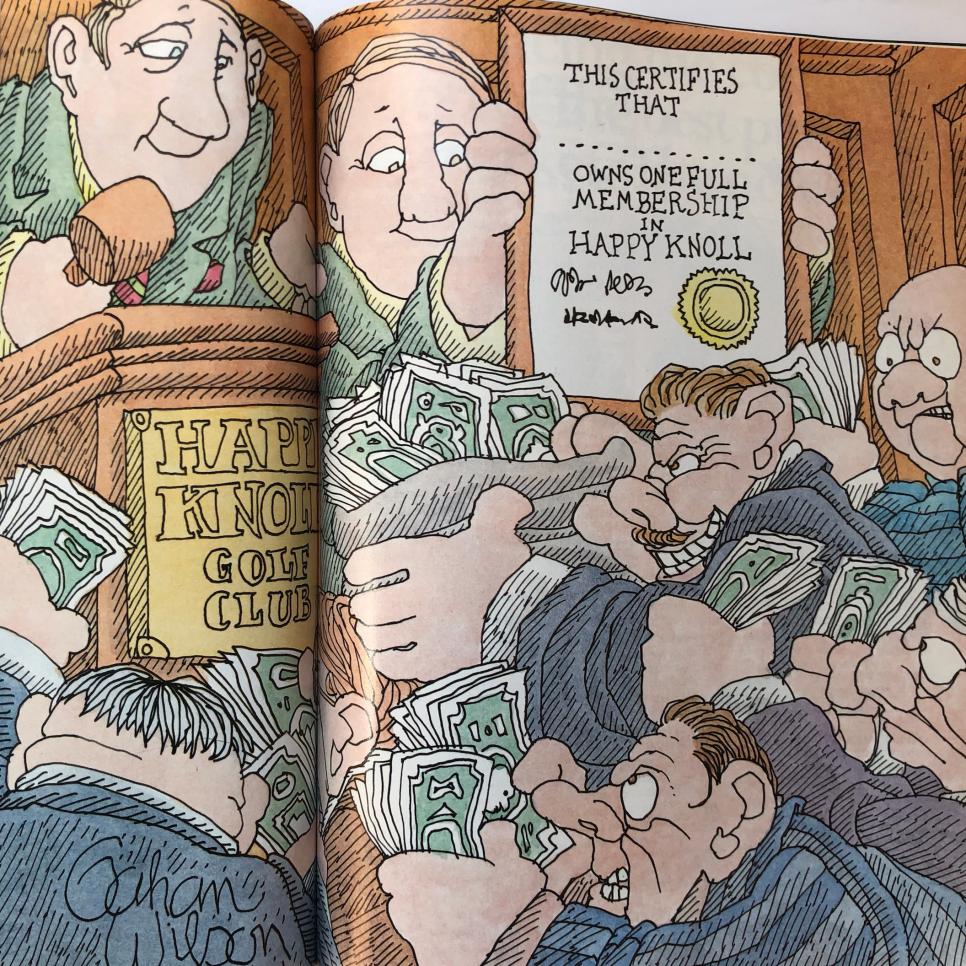

There might be excellent public courses in the vicinity, but no derivative zillionaire worth his indictment is going to be seen queuing at 5 a.m. for a 9:30 tee time at Bethpage Black or Montauk Downs. By his lights, it must be Happy Knoll (the fictitious club created by John P. Marquand) or die!

But membership, at least in clubs with name-droppable fellow members, is not simply a matter of writing out a check. Our aspirant must pass the scrutiny of the existing members. “He may come singing songs of Apollo or bearing rich gifts,” wrote Bernard Darwin in British Clubs (1943), “but the humblest, if there be enough of them, can bar the door against him.”

Darwin was writing in a golden age, now bygone, when standards were different and the members whose sponsorship could be bought for “soft dollars” kept their heads down.

Times change, however, values alter, men’s fortunes rise and fall, mortality intervenes. Nowadays, few are the gates that cannot be breached.

Today, traditionalists like myself consider the aggregate zeros of Forbes’ net worth represented by a given club’s list of recent rejectees to be as solid an earnest of its qualities as its Slope Rating.

But the fact is, we’re just kidding ourselves. Money has always talked loudly in American life, but in the last dozen years it’s been allowed to shout down every other voice in the room. This being the case, it seems appropriate to ask why golf clubs, like other social prizes (museum and hospital boards, for instance) shouldn’t simply put themselves up for sale and turn present-day socioeconomic realities to good and lucrative account?

The reforms would be few. Philosophically, I would urge that clubs adopt the position taken by Lord Chesterfield two centuries ago when confronted on a narrow London walkway by a notorious bully.

“Oi nivver gives woy to a scoundrel,” the bully announced.

“I always do,” said his lordship, stepping gracefully into the muddy gutter.

In other words, given the number of members he’s got in his pocket, Mr. Gotrocks is likely to get in anyway, so why not let the club itself profit from his keen desire? Why postpone the inevitable when, by succumbing to it now, the club can benefit materially? When you come right down to it, most clubs are of a size where one or two rotten apples don’t really spoil the barrel, especially if a sensible mechanism exists for periodically winnowing the membership roster.

The cost of your craving

A properly conceived club should simply auction off one or two vacant membership slots a year. To begin with, this will relieve the membership committee of the obligation to draw fine discriminations between equally unqualified candidates. If Horace Junkbond and Rupert Cablecast, whose only redemptive qualities are to be found on their Dun & Bradstreet statements, crave admission to Happy Knoll, let them put their money where their longing is.

Set a minimum bid, a sum sufficient, say, to resod the greens on the back nine, or to replenish the claret inventory, or to return members’ dues to 1937 levels, circularize the suitors and let the chips fall where they may. This way, all the members benefit, not merely those whose unspoken interest in Horace’s or Rupert’s candidacy is a nice new-money management account, an insurance sale or a handsome real-estate commission, or even a job.

Three rounds of bidding should do the trick, especially where you have two mighty packets of cash casting covetous eyes on a single slot. Bidding wars are terra cognita to the speculator, after all. Just drop the handkerchief and stand aside.

Call this vulgar, call this avaricious, call it what you will, but at the same time think about what an infusion of, say, $1 million of Junkbond/Cablecast’s steaming new money could do for your club. Others have. At least one well-regarded Texas club annually advises a select list of candidates of vacancies, with the highest bidders making the cut.

A tyrant’s guide to fellowship

Admission to a club is only the first step, however. Membership is an ongoing process. The flame must be tended. “It is the people as much as the course that form the character of a golf club,” the noted Glasgow golf writer S.L. McKinlay asserts in his foreword to the centenary history of Machrihanish. “What I most value is the enjoyment of being with kindred souls on a noble links.”

Clubs over time take on a character reflecting not so much their membership, but their leadership. Many of the best-run clubs have been virtual autocracies (one thinks of Clifford Roberts at Augusta National) run by decisive, dedicated, deeply involved men, fierce in devotion to their clubs, no sufferers of fools, cretins or poseurs; suspicious (sometimes to a fault) of the motives behind a given candidate. Such men establish standards that few in their orbit will dare truck with. Detractors will argue that autarchy is first cousin to tyranny, and once in a great while, I admit, a club president might go a bit over the top. In the last years of his stewardship of the affairs of Cypress Point, for example, the late Charles de Brettville conducted his office in a manner that would have drawn gasps of admiration from Stalin—and Cliff Roberts.

If a strong personality cannot be found, how then to stimulate kindredness? How best to keep the members on their mettle, how to see to it that their deportment consistently honors the spirit of the place, how to insure proper veneration of the ancient virtues?

It is too much to expect the members to police each other. Even in clubs whose governance is dictatorial, the fact that we live today in the most litigious society known to history might stay the autarch’s excommunicatory hand.

It has long been a truth universally acknowledged that no man is a hero to his valet. In an asylum, who will have the better measure of the inmates than the keepers? In the singular, special bedlam of a golf club, who is in a better position to pass final judgment on the clubworthiness of the members than THE STAFF: the people in the golf shop and caddie shack, the greenkeepers, the folks in the clubhouse?

My second modest proposal would therefore stipulate that each year, by secret ballot properly certified by a disinterested party, the staff shall have the right to “fire” 1 percent of the members excluding, however, in the interests of equity, those members who have bought their way in within the preceding five years.

I suspect that such a policy would put an end in short order to undertipping, stiffing the pro by patronizing Nevada Bob’s, being discourteous to waiters and caddies, failing to repair ball marks, bringing around the wrong sort of people, taking five hours to play 18 holes and many of the other forms of general churlishness that have made modern golf so iffy a social and sporting proposition.

Obviously such a system lends itself to corruption. It’s to be expected that Churl X, who’s bribed, cheated and mulcted his way onto the Forbes list, will see nothing wrong with slipping a discreet sawbuck here or there in the locker room or grill to make sure it’s Poltroon Y and not himself who gets the chop. So be it. Should an enlightened club management make bribery a single-fault misdemeanor, with the whistle-blower getting to hang onto the money, the possibilities for general improvements will be further enhanced.

If it seems desirable to keep the members themselves in the censorious loop, an intramember “relegation” system, in the fashion of the British soccer leagues, might also be instituted. Members could go after each other in defined categories—slow play comes immediately to mind—with a limit of three protests per member per protestee (to prevent mano amano vendettas). Point standings will be displayed weekly on lists posted prominently in the locker room and 19th hole. At season’s end, the names on top of each list would get the boot, with the right to reapply after a one-year probation.

Quite apart from its other merits, the manipulative and wagering possibilities implicit in this system seem, well, engaging, and should provide much merriment at club dinners and on those days when Nature red in tooth and claw renders the course unplayable.

Finally, if discipline in the ranks is to be ultimately maintained, there must be known to be one or two no-appeal, one-strike-you’re-out capital offenses for which permanent expulsion will be automatic. Two words will suffice to illustrate what I have in mind: cellular phone.

These are but preliminary thoughts on a topic whose surpassing importance should be self-evident. Any first-rate system will have to be refined over time. The Supreme Court continues to tinker with the Constitution of this great nation. Why should it be different with golf clubs? After all, which is truly nearer to God?