Of all the things golf has going for it, one thing it doesn't have is an Olympic heritage. Golf was included in the half-assed 1900 Games in France (historians call them the farcical Olympics), but just barely. There was a stroke-play event with all of 12 competitors, several of whom didn't realize that it was connected to something called the Olympics. There was also a full-handicap event won by a vacationing American from St. Louis named Albert Lambert. Wealthier than he was skilled, Lambert was nonetheless so delighted with his medal that, when St. Louis was awarded the 1904 Games, he managed to get golf included. Lambert's two claims to actual fame are that his company (later Warner-Lambert) invented Listerine and that he was the main sponsor of Charles Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight. He gave enough money to the effort that the St. Louis airport was eventually named for him. The golf on display at the St. Louis Olympics was not exactly international in scope, competed as it was by 74 Americans and three Canadians. One of the Canadians won, George Lyon.

Similarly, of all the things golf has going for it, it doesn't have much of a foothold in this year's Olympic host country, where the sport returns to competition. Brazil has roughly 200 million people, and its land mass is the fifth-largest on Earth. On such a massive canvas, there are only about 110 courses and 20,000 people who play. In Rio de Janeiro, host city and home to 6.5 million people, there are perhaps a few more than 1,000 families who belong to one of two private clubs.

People here are poor. The average annual income in Rio is approximately R$20,000 (about $6,000 in U.S. dollars). Steeply discounted memberships in Rio's two private clubs go for more than that. But it's also cultural. To understand Rio, one regular visitor said, you have to understand the beaches. This reporting trip began on what turned out to be a four-day weekend. My guide, Eduardo, had no idea what the holiday might be—his area of specialization is golf, and he had only recently resigned from Rio 2016's golf staff. Besides, he said, "Brazil has too many holidays." It turned out to be Dia de Tiradentes, which marks the hanging of an 18th-century revolutionary for advocating independence from Portugal.

In any case, walk Ipanema Beach on such a weekend. For four days and most of the nights, the entire beachfront is packed. Soccer and beach tennis are played every few yards. Watch the beach volleyball and realize what a weak facsimile the Olympic version is. These two-person sides feature rallies that last for a minute—and they're not using their hands. They tee the ball up on a mound of sand to kick it off and then use their heads, chests, knees, feet, occasionally backs or butts—to keep rallies alive. It's extraordinary. The people of Rio live for the beach. They live on the beach. Every kind of business is there on the sand—from alcoholic beverages to vendors selling corn on the cob to freaking massage. It's a complete and self-sustaining universe, and it's just as alive on the beaches of Copacabana and Barra da Tijuca and São Conrado.

Golf doesn't enter the public imagination. Most people know what it is, but it's not covered in the newspapers and it's not broadcast on television. It's nearly invisible.

And into these contexts, Gil Hanse has designed and built (with the help of his superintendent Neil Cleverly) an ambitious course intended not only to host the best in the world as they compete for gold, silver and bronze, but to become what Rio 2016 touts as the first public golf course in the country, a new beginning for golf and a bet on its future.

Photo by Dom Furore

OFF THE GRID

If golf does have a future in Brazil, it might be right here, on what is actually the country's first, and for now, only public course. The Associacão Golfe Publico de Japeri is about 70 minutes by car from the Barra da Tijuca section of Rio, site of the Olympic course. And believe me when I say "by car," which is the only way to get from Rio to Japeri unless you want a three-hour trip by bus, train and foot.

But Japeri is even farther than the mileage. When Eduardo told his mother the night before where we were going, she asked us not to. Japeri, a city of about 100,000 people, is notoriously violent and is last in the state of Rio de Janeiro's human-development rankings.

On our way to Japeri, Google Maps failed us, which was particularly disconcerting because we were nearly out of gas. (Eduardo had underestimated the distance.) But then, suddenly, just a few hundred yards off a new and desolate highway, there it was: a concrete bunker with a metal roof. Baked-dirt parking lot for maybe five or six cars. Fairways burned white by the ongoing drought. The range—the left half of which doubles as the fairway for the first hole—looks like an open, arid field. Which is exactly what these hundred acres were—a farm fallen into arrears on the outskirts of town—until about 15 years ago, when Jair Medeiros, a caddie from Gavea Golf and Country Club in Rio, along with a dozen other caddies, started bringing used clubs and balls back home and knocking them around.

One day, Jair approached the mayor about turning the tract into an actual golf course. The mayor was amenable, so Jair enlisted the support of Vicky Whyte, a Gavea member who's also the first female South American member of the R&A. It was her idea to seek funding for the enterprise by making it more than a golf course, a bastion of hope in a distressed place.

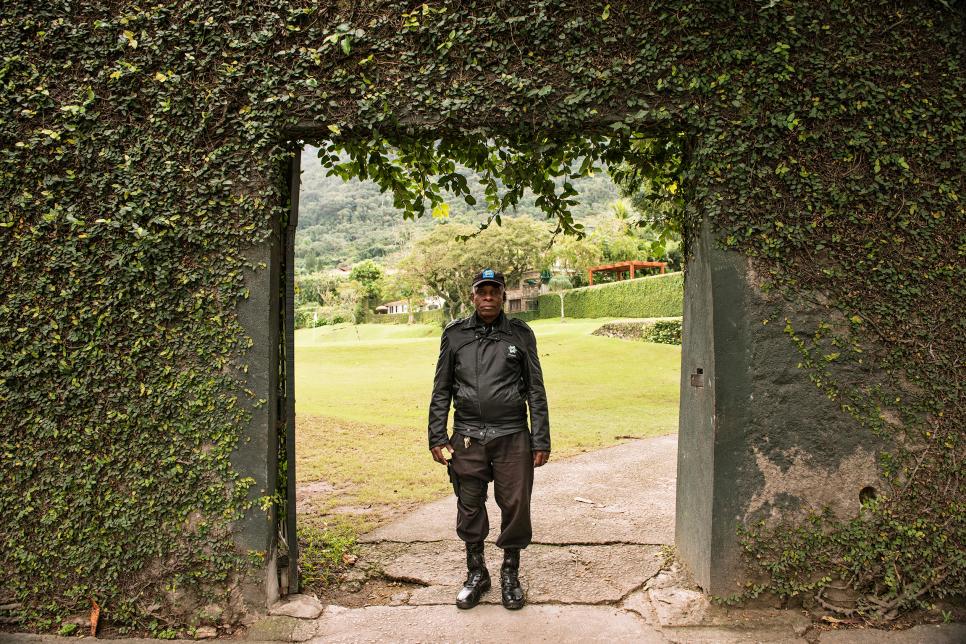

Five security guards patrol the course at all times, which is hard against a sketchy neighborhood that provides the club much of its workforce.

Whyte, with her son Michael, applied for a grant from the R&A and secured a sponsorship from Nationwide Insurance to build a course. The sponsorship was insufficient to fund 18 holes, so Whyte commissioned Brazilian architect Ricardo Pradez to build nine. "The construction process was slow," Whyte says. "Very little earth-moving and shaping was done. We went with the lie of the land. We did, however, build two lakes for drainage and irrigation purposes. Money was always a problem."

The course opened in 2005. Jair is now in charge and employs most of those original caddies from Gavea to maintain the facility.

The golf course is modest. Well, modest is generous. There is little irrigation—only the greens get water—so the course is as hard as rock. When the new highway came through, it stole three holes. Jair and his staff, with equipment on loan from the mayor, built replacement holes with the help of Fabio Silva, the agronomist at Gavea. Michael Whyte will tell you that the course forces you to use every club in your bag—the signature hole is a winding, downhill par 4 to a natural island green. But it's by no means a gimme that, were the flagsticks removed, most people would readily identify this place as a golf course. But, given what goes on at the academy (more on that in a bit), that's almost beside the point.

IN THE STADIUM

We're in another metal-roofed building. This time, it's the construction offices of the Olympic course, and we're talking to the only person in the world who holds the title of "Superintendent, Olympic Golf Course." It's right there, stitched on the breast of his dark-green shirt and matching cap.

This is the day before our trip to Japeri, and when Cleverly hears that we're heading there, says, "You're gonna see one extreme to another when you look at that facility, because it's still golf in some shape or form. But to transition to that from this is a huge, huge thing."

Cleverly is wiry, wired and intense. His bearing is military, which is how he spent his time before his career in golf. He's burned brown, not a natural shade for an Englishman. He was hired to take an inhospitable and inadequate piece of land (it's only about 100 acres) in a country where there is little inborn interest in the sport and, with an absolute dearth of experienced workers, help Gil Hanse build a world-class golf course. It is especially punishing to take on an Olympics during a crushing recession and only two years after hosting a World Cup. On this day, Cleverly was 104 days away from the beginning of the Games. When his course will then be trod upon by caddies and players and beat to hell by 15,000 ticket holders per day, and none of it, not one square inch of it, has ever really been tested. Well, unless you count the single rehearsal event, in which a couple dozen Brazilian pros played in front of a few hundred spectators and, even then, the roping was all screwed up and players got touchy when the crowd jostled them. One hundred and four days, and he still doesn't have enough mowers. He's also waiting for someone at the organizing committee to approve and organize the logistics to bring several dozen volunteer superintendents from around the world who are willing to pay their expenses and donate their time and labor to get the course into the pristine shape that the only course ever built for Olympic golf deserves.

It has been a challenge, and it's going to continue to be one. But when you're out on the course with Cleverly, and he shows you the green complex at No. 7, the way the rhythm of it is set up by the false front on the left side of the green, which falls gently toward the center, where it's joined by the razor edge of the bunker face, which rises to create an almost musical symmetry—his love of this course and all the pain it has caused him is right there in his eyes, even though he deflects any credit from himself and pronounces Gil Hanse "an artist."

When you ask Cleverly what this course's future is, it's a loaded question because, though he has worked on 11 other courses, this is the one by which the world will judge him. More than that, he's deeply concerned whether this course is an opportunity Brazil is capable of taking advantage of, or, like so many former Olympic facilities, it will fall into disuse. "The only answer I can give you would be the 'if' scenario," Cleverly says. "If there would be a street-level golfing commodity, I'd say that this golf course would be the most played on a regular basis. But because I feel now, having been here for the last three years, and realizing that unless things change from a street level—the price of equipment, the price of a round, the mentality of people ... from what I've learned in my time here, it's really hard for people to live normal lives in this country. So there has to be some kind of format where they can exhibit the golf course to juniors or schoolchildren. Bring them to the driving range, show them how to play golf, and if you get a percentage of those that are interested, then maybe there will be the roots of something in Brazil. It's easy to talk a good game and to say that you have some kind of a plan, but whether they step up and do it is another matter."

BACK IN TIME

It was a different world in 2009, when Brazil won the Olympic bid. The country was in the midst of an economic miracle. There was a burgeoning middle class benefiting from an oil boom, and a robust demand for the commodities in which the country is rich. There was a new population buying houses and flat-screen TVs. These were the people the Confederation of Brazilian Golf (CBG) saw as the future. Rather than improve Itanhanga Golf Club, they decided to build a new course that would be open to the public. They even laid plans for a center where people could be taught the job skills of course maintenance and management.

Nico Barcellos was hired as the CBG's technical director and national coach—to be the guy who would, in Cleverly's words, "step up and do it." Before 2009, the CBG was largely a social organization, run by a volunteer staff. Barcellos hired his people—four regional instructors to standardize teaching methods and to initiate outreach programs that would bring golf to the children in the town's schools.

Barcellos is a lanky, friendly guy. He started playing when he was 6, won the Brazilian Amateur for the first time at 17, and then won it six of the next eight years. He went to college at the University of Georgia, won the SEC Championship, then played professionally for 12 years and won 11 events in Brazil. He's proud of the strides he has made in his new job, and proud that two of the last three Brazilian Opens were won by Brazilians.

But you've got to kind of feel for Barcellos. The economic miracle is over, victim of collapsing commodity prices, governmental incompetence and corruption. The middle class has largely disappeared. Unemployment is at unprecedented highs. He's left to grow the game in a country that can't really afford it.

"Do you know SNAG [Starting New At Golf]?" Barcellos asks. "It's a plastic club, a tennis ball, and the ball sticks on a target. We teach physical educators how to teach golf in school with it. And now we have 50,000 kids playing in school. The second stage is to get the most talented players from the 50,000 and maybe get 100. And then take them to the golf course."

The R&A invests £50,000 annually in Barcellos' program, called Golf for Life, which has trained 375 gym teachers and introduced another 60,000 people to the game on beaches, in Olympic centers and on the street.

There's space at the Olympic course for a golf academy, just between the sleek, modernist clubhouse and the expansive practice area. Whether one will ever be built is an open question. As Barcellos says, "Once the economics go bad, golf goes bad."

Photo by Dom Furore

ONE SHOT AHEAD

How does Neil Cleverly imagine his Olympic course in five years? His contract is up in December, and someone else is going to have to take over the management and upkeep.

"The legacy of this golf course is going to go one of two ways—it's going to go down very fast or it's going to go up very slowly," he says. "And I'm hoping it's not the former."

So back to Japeri. If the future of golf in Brazil is to go up very slowly, then we need to understand what is really going on at Japeri, the country's only public course and golf academy.

In 2008, the average income in Japeri was $R5,000, or about $1,400 U.S. per year. It's likely less now. Private donations helped to create a golf academy for children from the town's five public schools.

And here they are—about a dozen of the 120 current academy members—at Japeri on a Sunday in April to put on a demonstration for two visiting staffers of the R&A. The explicit goal of the academy is, yes, to teach these 10-to-18-year-olds golf, but, more important, to get them through school.

The kids space themselves out along the roped-off hitting area of the range and start banging balls. Breno Domingos, 18, carries a 2-handicap and works part-time for the academy from which he graduated. Right now, he's helping a younger boy with his setup. According to Vicky Whyte, both of Breno's parents are unemployed—his father was a painter. The family is getting by on Breno's salary. In addition to his work at the academy, he's on scholarship at a private university, Estácio, studying civil engineering, mostly at night and online.

Each of the 120 students comes to the course three days a week, either morning or afternoon. They apply to the academy through their schools and are evaluated by Jair and his staff. Upon acceptance, each of the students is provided two T-shirts, two polo shirts, a sweater, a golf cap, socks and a pair of shorts. On site is a full-time tutor to help with homework. There are four full-time golf instructors, including Jair. Dental care is provided, as are snacks.

Japeri is run on a shoestring, but it has conspicuous successes. One of its female graduates, Thuane de Oliveira, is fifth in the national rankings. She has completed high school and is studying radiology. And on the day of the exhibition, there is a male graduate of the academy, Christian Barcelos da Silva, tied for the lead in the Brasilia Open. By the end of the day, we'll learn that he finished second. He has been offered scholarships to two universities in the United States—first, though, he must finish his requirements and graduate high school.

To us, in the United States, this all sounds kind of commonplace. But here, it's a miracle.

THE OLD GUARD

There aren't many quiet places in Rio de Janeiro. Gavea Golf and Country Club is one of them. The geological features that make Rio one of the world's most beautiful cities—mountains like Sugarloaf, around which the old downtown is built, or Two Brothers, which looms above the beaches—is the setting into which Gavea nestles. The course, created in 1926 by visiting English and Scotsmen, features elevation changes of 100 feet—tee balls drop from the sky down to narrow fairways, and irons soar up toward greens built on the edges of cliffs. The mountain named Pedre da Gavea rises above the second, third and fifth greens, looming larger as you progress through the course. To its right, thousands of feet up another mountain, is a concrete pad from which hang gliders launch. The sky is filled with them. We are in the middle of the city.

Every day, Brazil's greatest golfer, Mario Gonzalez, who, in the 1940s and '50s competed with Roberto De Vicenzo to be the best golfer in South America, comes to Gavea. He is 93 now, and it's only his statue, just off the first tee, that still swings a club.

The quiet here is purchased. Five security guards patrol the course at all times, two on its southern border, which is hard against a sketchy neighborhood that provides the club much of its workforce.

Very little changes at Gavea, protected as it is by the mountains on two sides and guards on the others.

But just a few miles away, on a formerly inhospitable piece of land, there's a golf course, links style, that's wide open. Once the Olympics are through, it will, theoretically, be open to anyone. The challenge now, is to make the new golf course the beginning of something.

FOUR MAJORS ISN'T ENOUGH

Whatever the future of golf in Brazil, the real impact of a sport's inclusion in the Olympics is certain to be much broader. There are large swaths of this planet where the game is still barely known. Becoming an Olympic sport can and does lead to increased governmental funding and the creation or expansion of programs to attract new players.

Recall that tennis returned as an Olympic sport in 1988, a moment at which its participation in the United States was beginning to decline. In that year, 147 countries were members of the International Tennis Federation. Now, 28 years later, the number is 211.

More telling are the draws in the majors. In 1988, the men's singles draw at Wimbledon had 25 countries represented. In 2015, there were 44. Among the countries where tennis had only the weakest perches before 1988 are such modern giants as Russia, South Korea and Serbia, whose three best players—Novak Djokovic, Ana Ivanovic and Jelena Jankovic—were all infants when tennis was reintroduced to the Olympics. Each has attained the World No. 1 ranking.

"Our belief is that the additional support given to any Olympic sport by National Olympic Committees helps to grow the sport in that country, and that this 'Olympic effect' has broadened tennis significantly," says Barbara Travers of the International Tennis Federation.

Asked about this Olympic effect, Kevin Barker, the director of Working for Golf of the R&A, agrees: "The Olympics represents a golden, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for golf to showcase itself to millions of people around the world. In many countries we are already seeing an effect as government funding has been made available to the sport. And there is no reason why that should not expand." —David Granger

EDITOR'S NOTE: David Granger served as the editor-in-chief of Esquire for 19 years, stepping away from the magazine in March. He plays to a 6.2 Handicap Index and isn't afraid of Zika.