The Loop

A son reflects on a father, a request, and an act of kindness from Arnold Palmer

This is the story about a father, two sons, a letter and Arnold Palmer.

The father had been playing golf for about two decades, taking it up at the suggestion of a neighbor after moving his young family from the New Jersey shore to a small Connecticut town some 80 miles northeast of New York City.

There were and still are no golf courses in this sliver of a town, small enough in area that you can drive from one end to the other at its furthest point in about 10 minutes. But there is a course in a neighboring town, about seven miles away through windy and wooded back roads. That’s mostly where the father, who worked in finance and cleaned his clubs with the kind of detail an accountant would, and his group of friends would spend part of nearly every weekend morning from April to October, 18 holes on Saturday, another nine holes on Sunday.

Eventually the father would pass various clubs down to his two sons. The first ones were a set of Palmer Peerless, with woods made of persimmon and irons the size of butter knives. Sometimes he’d even take the two boys with him to play. He was no scratch golfer, usually hovering between a 10 and 12 handicap, but the two lads, playing only on occasion at that point, were much worse.

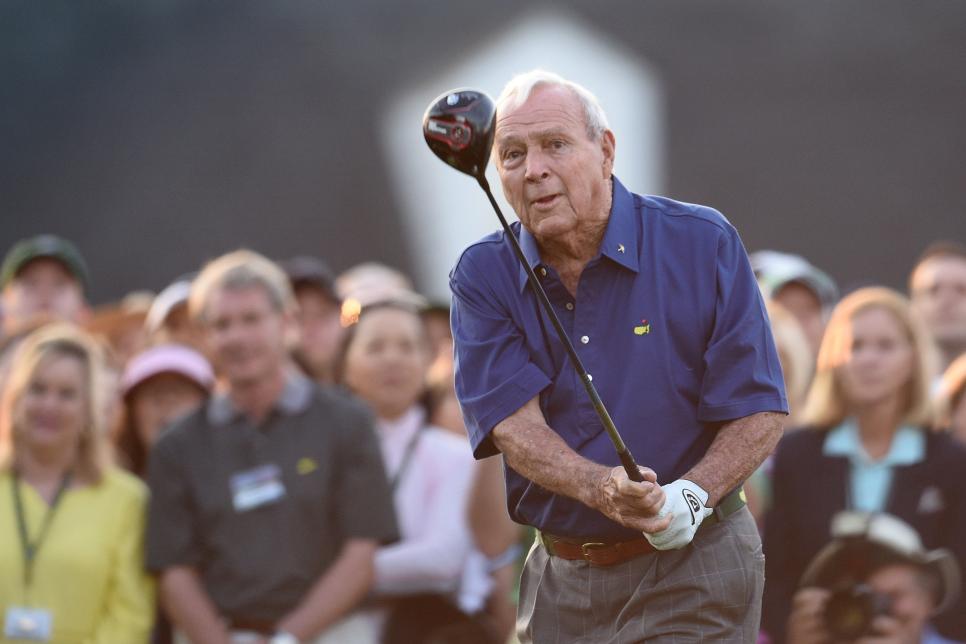

It was the 1980s and Palmer was a decade removed from the last of his 62 wins on the PGA Tour, though he would add another 10 on the Senior Tour and continue to be a presence in the game for decades. The father, 18 years younger than Palmer, had always been a fan even before taking up golf himself. Hell, everyone of that generation liked Palmer, who was always the coolest, toughest, nicest and most beloved guy in every room.

But the truth is the father liked Jack Nicklaus more. They were closer in age. The Golden Bear was more prominent (see: the Masters, 1986). He was the best of all-time at that point, something the father could appreciate given his competitive streak that stretched to long before his days as a college tennis player at a small Division III college in Alabama.

And perhaps because the father was also shortish (5-foot-10), stocky (read: fat) and had blonde hair (albeit a bit darker) and blue eyes, the old man could somehow dream the dream. Even some of his golf attire resembled that of Nicklaus’.

Getty Images

Then one day early in 2001 one of the sons bought the father a copy of Palmer’s first autobiography, A Golfer’s Life, for his birthday, getting Palmer to sign it during a trip to Bay Hill before wrapping it up.

Reading it, the father was reminded of Palmer’s blue-collar background, the same kind he had originated from, and Palmer’s relationship with his own dad, Deacon. It also touched on Palmer’s battle with cancer and recovery from it.

The two boys’ mother was the voracious reader of the family, churning through one novel after another when she wasn’t shuttling them around for kid things, but the father was a softie and a sucker for a story like Palmer’s. Just like that, Arnie was No. 1 and Jack No. 2 in the big guy’s eyes.

A little over a year later, the father was diagnosed with cancer, too. Only it was malignant melanoma, the most dangerous type of skin cancer, and it had already progressed to stage 4, metastasizing beyond the lymph nodes into other parts of the body.

Surgery wasn’t an option, chemo and radiation could only do so much and experimental trials were a miracle at best. Soon, the occasional swelling in his left leg became permanent and tumors bubbled to the surface. He needed a cane and care and all the things that go with fighting a horrible disease, including something that could cheer him up, even if he rarely complained.

Knowing there would be no more foursomes in their father’s future, the two sons wanted to do something special for him in the time that he had left, so one of them reached out to Palmer through his representative and right-hand man, Doc Giffin. Explaining the situation, they hoped the King could maybe send an autographed picture. Anything really. It was a long shot, they figured.

On Sunday night in Pittsburgh, Palmer passed away at the age of 87. An outpouring of tributes followed as he was remembered for his life, legacy and the impact he had on millions of people, including those he never even met.

Getty Images

Thirteen years and one day earlier, a manila envelope arrived at a house in a small Connecticut town around 10 a.m. On the outside, was a return address label that featured a multi-colored umbrella. Inside, there was a signed photograph with a letter that opened with the following words:

“Jim, I understand that you’re not feeling well…”

On it went for a full page. There was detail and grace and kindness throughout, a real connection, even though the author and its recipient had never met or spoken to one another.

It was signed Arnold Palmer, and it was addressed to Jim Wacker. Our dad never got to see the letter that day. He passed away a few hours earlier.

Eventually, I got a chance to thank Palmer. Though it was the kind of thing he had done countless times before there was no form-letter feel to his message. It was personal.

It’s also why he will live on forever, even for those who never met him or got the chance to read his letters. For them I say thank you, Arnold. Thank you.