News

The 1986 Masters: A Father-Son Moment

"Hey, who is that guy?" asks Jackie Nicklaus, pointing to the TV and the image of a middle-age golfer in a yellow shirt holing a curling 22-foot putt for birdie on the 11th hole at Augusta National.

Jackie gives his dad, who is plopped on the living-room sofa next to him, a playful nudge with an elbow. Jack Nicklaus doesn't budge. He is watching the big screen, rapt. The Nicklaus men have a rare weekday afternoon to kill, and they're viewing, for the first time together, the complete CBS Sunday broadcast of the back nine of the 1986 Masters.

For two sports junkies, this is as good as it gets. Snacks are scattered about Jack's comfortable North Palm Beach home. Barbara Nicklaus is wandering in and out, asking the guys periodically if they need anything. The family dog, Bunker, a chocolate Labradoodle, is slumbering nearby, head on his paws. A few friends are over and are quiet, eager to hear what the video can pry loose from Jack's considerable memory.

"Stop the tape," Jack says. "I just noticed something." What follows is a litany of recollections and insights on probably the best nine holes of major-championship golf ever played, which ended with Nicklaus winning a record sixth Masters and the last of his 18 major championships as a professional.

Jack has recounted the essentials of the back nine before—the famous eagle at No. 15, the near hole-in-one on No. 16, the killer birdie at No. 17, the embrace with Jackie, then 24, as they strode off the 18th green. But Jack, always a good interview, has tended to talk about that Masters in a clinical, matter-of-fact way that emphasizes the method more than the magic. Posterity begs a fuller remembrance, because an entire generation wasn't yet born when Nicklaus won that Masters. The generation before is acquainted in only a highlight-reel kind of way: Tiger Woods, for example, was 10 years old. As for the generation before that, well, time erodes recollections of everything.

After a friend hits "pause" on the remote, Jack nods toward the screen. "See the yellow shirt? Many years ago, the 13-year-old son of Barbara's church minister died of cancer. The boy's name was Craig Smith, and before he passed away he told me he loved watching me play on Sundays, and how he liked it when I wore a yellow shirt because it always seemed to bring me luck. I remember Barbara telling me to wear yellow that Sunday morning, that it would bring me good luck because of Craig."

The tape resumes for only a few seconds before Jack asks that it be paused again.

"See how narrow my stance is on that putt at 11? Through the years, I usually placed my feet about 10 inches apart.

That week, I began placing my feet much closer together, very narrow. It helped me swing the putter more freely, move the handle better."

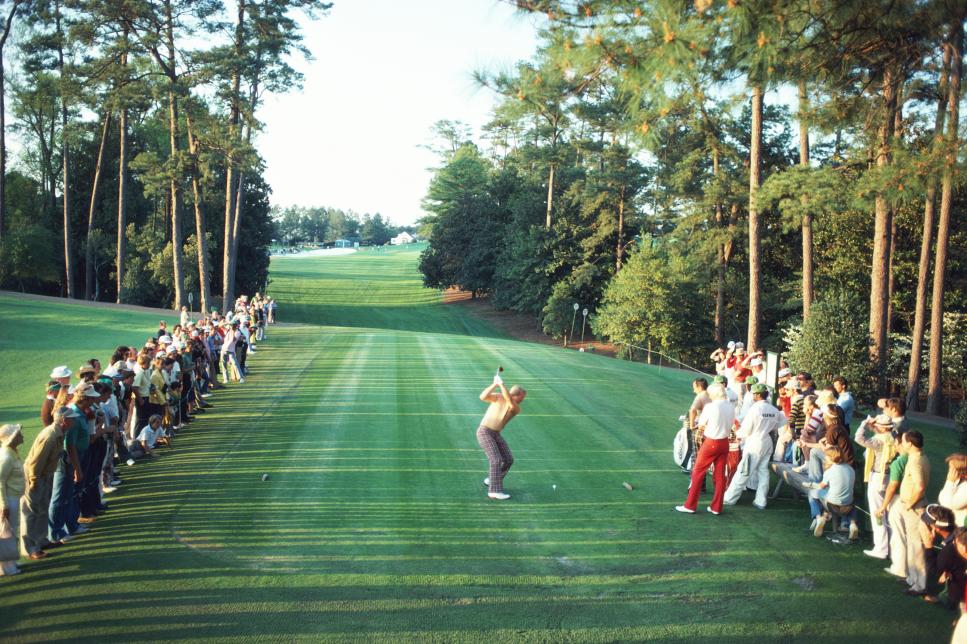

Brian Morgan

Nicklaus was 46 when he came to Augusta that year. He hadn't won a major in six years or a tournament of any kind in two. He had missed three cuts earlier that year. "I was between things in my life," he says. "Senior golf was still pretty new and was down the road. My business was fine, but it didn't take up all my time. I'd play some golf, 12 to 14 tournaments a year, not enough to keep me sharp, but enough to be somewhat competitive. I was neither fish nor fowl. I wasn't really a golfer."

He opened that Masters with rounds of 74, 71 and 69, hitting the ball well but not making putts with his Response ZT, which had an enormous head and looked out of character in the hands of Nicklaus, a traditionalist. When the final round began he was tied for ninth, four shots out of the lead and barely lurking. He was even for the round after eight holes, the number of players ahead of him surging to a dozen. But after Jack birdied Nos. 9, 10 and 11, he suddenly was only two strokes behind the leader, Seve Ballesteros. Greg Norman was one of the men still leading Nicklaus. So were Tom Watson, Tom Kite and Nick Price.

GETTING EMOTIONAL

The tape is running again, and Nicklaus is approaching the tee at the par-3 12th. "Here I'm thanking the people, who always were so fantastic there," Jack says.

The applause is sustained, and a friend points out an observation Jack once made about his getting emotional midway through the back nine, and how it threatened to distract him. Jack always said the tears began surfacing somewhere around the 15th hole, and he repeats it now. But Jackie corrects his father, softly. "Actually I saw it as you walked up to the tee on 12," he says. "You had to collect yourself there, Dad."

"Well, it wasn't the first tournament where I became emotional," Jack says. "The first time I had a gallery that made me cry was on the 11th hole at Muirfield at the British Open in 1972. I had won the first two legs of the Grand Slam, and on the last day I shot 32 going out. After birdieing the 10th, I hit an approach shot stiff at the 11th. As I walked up the fariway, the gallery exploded. The next thing I know, I've got tears streaming down my face. It wasn't for Jack Nicklaus the golfer, it was for me. That's what was so nice about it."

Now Jack is seen staring at the 12th green at Augusta, pensive, hands on his hips.

"I turn around from that applause, and now I'm facing the 12th hole at Augusta National. You can see a look of concern on my face. I'm concerned about what I have to do, the shot I have to play, my strategy. I've put myself back in the tournament; now what am I going to do that's not stupid? I can't go right, and I don't want to be in the back bunker. I need to calm my nervousness, because I've just made three birdies. All I want to do is put the ball in play."

Augusta National

Jack pulled the ball long and left at the 12th and made a bogey, a spike mark deflecting a six-foot putt. He fell three shots behind. The Nicklaus' close friends, Pandel and Janice Savic, thought Jack was out of the tournament and left for the airport. "That bogey was probably the best thing that happened to me during that round," he says. "I didn't feel good about it at the time; in fact I felt terrible about it. But it was a wake-up call, a kick in the rear end.

"If I had parred 12, I might have played a more conservative tee shot on 13 and ended up hitting my second in the water," he says. "You just never know. As it was, I took a 3-wood and turned my ball around the corner on 13 and set myself up for a birdie that kept the round going."

As the Nicklauses walk up the 13th fairway toward the tee shot, they chat freely. As Jackie points out, they had a history as player and caddie.

"I'd caddied for my dad many times before," Jackie says. "The first time was at the 1976 British Open at Birkdale [Jackie was 14 at the time], when Dad's regular caddie, Jimmy Dickinson, tore an Achilles tendon during a practice round. I stepped in and picked up his bag. Dad tied for second that year. I caddied for him quite a few times after that."

Jack points out that Jackie wasn't the only son to caddie for his father. Steve Nicklaus was the first to be on Jack's bag when he won, at Colonial in 1982. Gary caddied at the International at Castle Pines, where on the ninth hole one year, he got a nose bleed because of the altitude. Jack's daughter, Nan, didn't caddie, but she traveled with her father to more than one British Open, a daddy-daughter excursion of the highest order.

A joke is made about the sparkling-white caddie uniform Jackie is wearing. "Yeah, it made me feel like a Good Humor man," he says. "It looked funny, it was hot, and the pollen from the trees would cling to it. I had allergies, and when I'd bring my arm up to scratch my nose or to cough, the uniform made it worse."

"It wasn't the worst year for pollen, though," Jack interjects. "There were years where you were just covered with it. My contacts, some years I couldn't understand why my eyes hurt so badly."

Nicklaus reached the par-5 13th in two easily, and a two-putt birdie brought him back to within two of the lead. He parred the 14th, but Ballesteros eagled the 13th—his second eagle of the day—to take a two-stroke lead over Kite, with Nicklaus four behind.

A brief interlude involving Ballesteros and his caddie and brother, Vicente, gets Jack's attention. After Seve hits his second shot on No. 13 to eight feet, Ballesteros, grinning broadly, shakes hands with Vicente, then doffs his visor.

"It's like Seve was saying, This is my tournament, guys. All I need to do is finish it," Jack says. "Little did he know. Me, I wasn't thinking about what Seve was doing. I had my own problems. When was the last time I could control what somebody else did, other than through intimidation?"

Says Jackie, "Watching Seve shake his brother's hand like that reminds me of how wary I was of getting too excited myself. At the 1982 U.S. Open at Pebble Beach, Dad bogeyed the first hole, parred the second and then made five birdies in a row. I remember walking off the seventh green and saying, 'Way to go, Dad, this is great!' He then bogeyed the eighth hole. In my mind, as a caddie, I thought maybe I had something to do with that."

"Yeah, shame on you," replies Jack.

"You would have won more majors without me," laughs Jackie. "But at that Masters, though I was very excited and emotional, I kept my feelings in check. I would say, 'Let's make another birdie,' 'Let's hit another good shot,' 'Keep your head still,' things like that."

CBS didn't show Jack's tee shot at the par-5 15th, underscoring the fact that he still was not seen as a serious threat. The telecast picks up with Jack addressing his ball fastidiously. "I had 212 yards to the hole," Jack says. "I remember saying to Jackie, 'How far do you think a 3 [eagle] will go here? And I don't mean a 3-iron.'"

"I told Dad, 'Let's see it,' " replies Jackie.

"I just loved the way that shot set up, because I could go right at the pin," Jack says. "At Augusta you always have to protect against one side of the green. Trouble always seems to be on one side or the other, depending on where the hole is. On 15 that day there was room on the left and right, and I could go right at it. I had a lot of confidence standing over the ball. I chose a 4-iron and hit the ball solid, very high, the ball stopping just a shade past the hole and to the left, about 12 feet away."

On the TV, Jack gives an exclamation with his fists.

"I got a little excited there," he says. "Got a little charged up. At this point I didn't know how far behind I was, and I didn't care. I've always been a leader-board watcher, especially coming down to the end. But in this case I only knew I was behind and the leader board didn't make any difference. Seve could have gone from nine under to two under, and it wouldn't have made any difference to me. I was five under par, and all I cared about was getting to seven under."

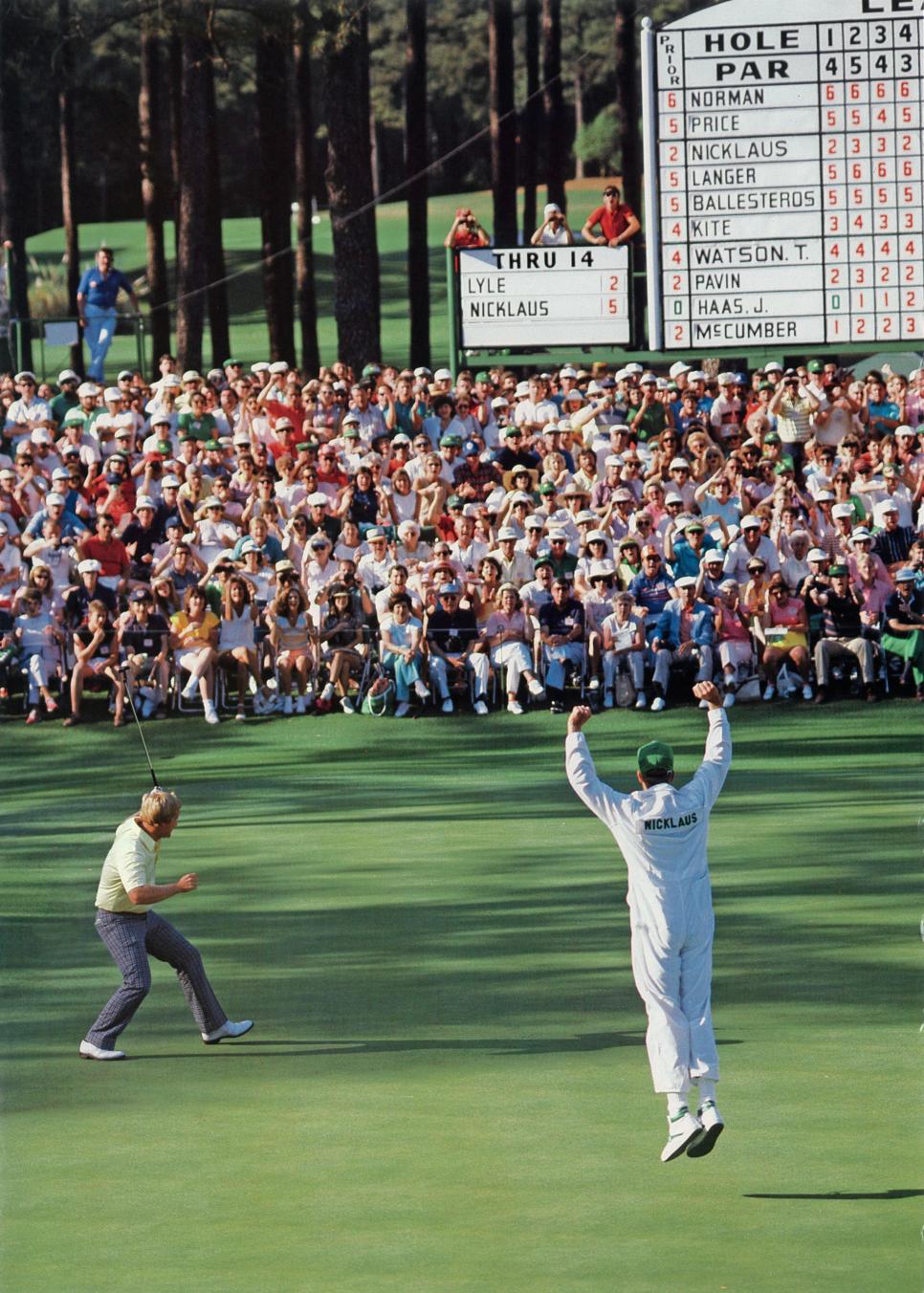

The putt for eagle on No. 15 was slightly uphill and broke two to three inches to the right. Jack notes he had faced a similar putt during the 1975 Masters. Such is the acuity of Nicklaus' memory, with the video there to prompt him. As the ball nears the hole, Jackie bends at the knees, and when it drops he leaps and claps his hands.

"When that putt went in, I was watching Jackie more than anything else," Jack says. "I told him, 'If you could jump that high at North Carolina, you'd be playing basketball.' That was the first time I realized I could win the tournament."

THE DRAMA OF A NEAR ACE

Jack and jackie are leaning forward on the sofa now, the finish looming like the last minute of a championship football game. The final act begins with Jack's birdie at the 16th hole, which might be the most replayed episode in the history of televised golf. It's a monolithic moment, the sequence of events a confluence of perfect TV announcing from 26-year-old Jim Nantz (working his first Masters) and Tom Weiskopf (runner-up four times at Augusta). Jack and Jackie are wide-eyed watching it.

"I had 175 yards to the pin," says Jack, noting the traditional Sunday hole location. "I could hit either a hard 6-iron or put a 5-iron up in the air. I could even have faded a 4-iron, but it didn't set up for that. It by far is the easiest hole location on that green, because a ball hit to the right will feed to the hole. Even a few feet long is OK. But the key is, you've got to get it to the hole. If I don't hit the 6-iron quite perfectly, it's not going to get there. Short is no good."

Augusta National

Weiskopf, asked by Nantz what is going through Jack's mind, says, "If I knew the way he thought, I would have won this tournament." Part of the ensuing comments gets Jack's attention.

"It's interesting what Weiskopf said while I was preparing to play," Jack says. "Tom says, 'Stay down, accelerate through the ball, make the swing you're capable of making.' That was Tom's thought pattern, but my thought pattern was not that. Mine was, I've got 175 yards, I've got to hit the ball high in the air, I need to hit it softly. Make that swing. Some people think about what they're mechanically doing through the ball. I think about what I want the clubhead to do through the ball to make the ball do what I want. People look at things differently. There's nothing wrong with what Tom said; it's fine, and he was a very good player. But I didn't play by swing mechanics, I played by feeling things that would make the mechanics happen."

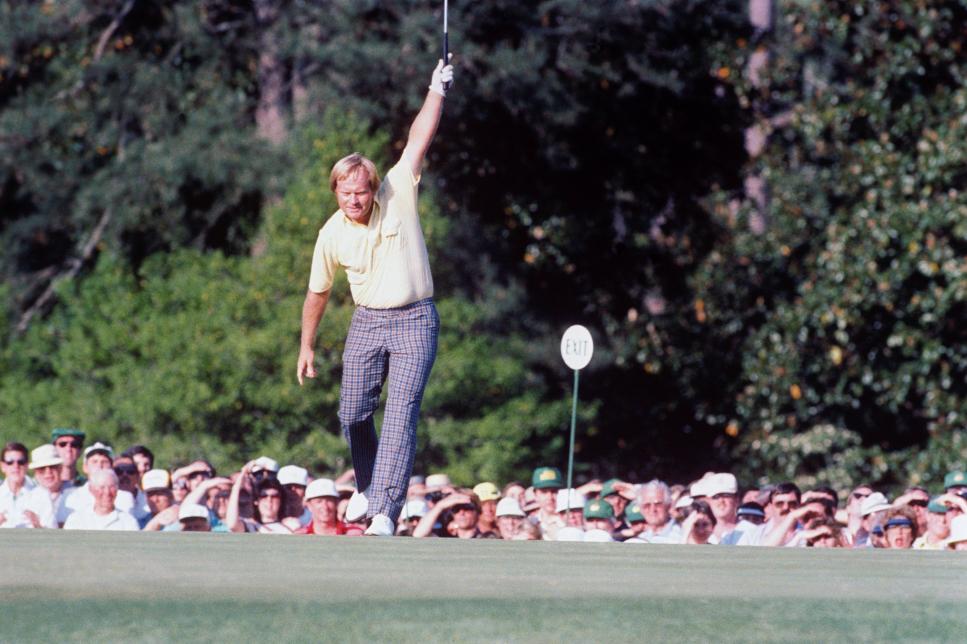

The ball lands and checks, then spins to the left, narrowly missing the hole, and stops 3½ feet away. Of his reaction to the shot, Jack says, "The remark I made was probably the cockiest I've ever made in the game of golf. While the ball was in the air, Jackie said, 'Be right!' And I just picked my tee up and said, 'It is.' " Jackie interjects: "He said it quietly."

The gallery, on the other hand, was not quiet. There was bedlam in the amphitheater surrounding the hole, that roar only increasing as Jack approached the green. The spectators quieted as he surveyed the putt, hardly a kick-in. "It was no gimme," he says. "It was a 3½-footer with a left-to-right break. If I hadn't hit it firmly, it would have broken off." But in it went, dead-center, and the roars were even louder and more sustained.

"I've been to a lot of concerts and a lot of sporting events, and I've never heard anything that loud," Jackie says. "The noise left my ears ringing. It was especially loud walking from the 16th green to the 17th tee. The cheers were coming down on top of us. I remember putting my arms around Dad's clubs as we walked between the people, to protect them, and the people were leaning over and shouting.

It was overwhelming, really."

"I can't imagine why they were going crazy," says Jack, wearing a look of mock surprise. "But seriously, the 16th is at the bottom of a valley. You have the sounds coming off the hillsides, the trees, the lake. It's a loud, loud place."

ANTICIPATING SEVE'S DISASTER

The roars emanated back to the 15th fairway, where the tape shows Ballesteros, his lead down to one stroke, facing what appears to be a routine 4-iron second shot to the green. In fact, the lie was awkward. Kite, Ballesteros' playing partner, later noted that Seve's ball was on the downhill side of a mound in the fairway. Ballesteros proceeds to make an awful swing, the ball immediately fluttering to the left and landing in the middle of the pond fronting the green.

"I was talking to Seve at the Champions Dinner early in the week," Jack says. "He told me he hadn't been playing a lot of golf, period, and not much tournament golf, and wasn't as sharp as he needed to be. Now, every time I wasn't sharp and I got in a tough situation, I would never take more club and hit it easy. You're much better off taking less club and hitting the ball harder. At 15, he picked an easy 4-iron rather than a hard 5-iron, and you can just see that he quit on it. It didn't get halfway across the water. It was not a good shot. Frankly, I expected that somewhere during the week from Seve, but it didn't happen until 15."

But what about the roar Jack provoked at 16, and his comment earlier about his ability to intimidate other players?

"When I heard the noise [after Ballesteros' shot], it was a blend of loud roar with a deep-sounding groan underneath it," he says. "It was not a nice sound. I've never wished anyone bad, but I knew exactly what had happened. People were yelling at me, "It's in the water! It's in the water!" and I'm thinking, I know that."

Walking toward the drop area, Seve is far from shaking hands with brother Vicente. In fact, they are walking 10 feet apart and are not speaking. "At that point, Seve knew he was out of the tournament," Jack says. It's pointed out that even with the eventual bogey, Seve still is tied for the lead with Nicklaus and Kite. How could Ballesteros possibly be out of the tournament?

"In his mind, he's gone," Jack repeats. Nicklaus pulled his tee shot on No. 17 down the left side, just into the gallery but with an ideal angle to the flagstick on the right. "I think I had 112 yards to the hole, which meant I could hit a pitching wedge and not be long. I hit it 12 feet from the hole." The putt was devilish; Jackie saw it breaking to the right but was overruled by Jack. "No, Rae's Creek will pull it back to the left or straighten it out," Jack replied. (See "The Red-Dot Rule," page 134.) The ball did just that, and there's no Masters photo more ubiquitous than the one of Jack following the ball into the hole with a large step and thrust of his putter. Incredibly, Nicklaus led the Masters.

"In the years after that, Dad and I stuck tees in the ground at the spot where the hole was, trying to 'make' that putt again," Jackie says. "We haven't made it, not once." Adds Jack: "It always breaks to the right now. They've resodded the greens many times since 1986, and it's a slightly different putt. But the point is, I haven't made it."

Jack is intrigued by the technical challenges of the par-4 18th hole as he sees himself preparing to hit his tee shot. The 18th is not the most difficult hole in championship golf, but many Masters have been lost there, and Nicklaus wasn't about to take a big risk. "I chose the 3-wood," he says. "There are two fairway bunkers, and I knew the 3-wood wouldn't reach the second, although it could reach the first. My line was in between the two, and you can see me swinging beneath the ball to make sure the ball didn't go left. I hit a nice little fade. I left myself 175 yards to the hole."

It takes a long time for him to hit that final approach shot. "I was between a 5-iron and 4-iron," Jack says. "Eventually I took the 5-iron, knowing I needed to get all of it to get the ball on the top level, where the hole was. I hit the ball really well, but just as it left the clubface I felt a little breeze in my face. The hole was all the way in the back of the green, and when the ball stopped on the lower tier I thought, Great, now I've got this darned putt." He faced a 40-footer, up the tier that dissects the green. Fortunately for Nicklaus, his design company had overseen the rebuilding of several greens at Augusta, including the 18th. "Some were too severe from back to front," he says. "They had been at about an 11-degree pitch, and we modified them to 8 degrees. I knew that putt on 18. I'd practiced it many times."

Jack's lag stopped six inches short of the hole, dead on line, a feat which, under the circumstances, awed his son.

"I'm not exaggerating when I say that was one of the best shots he played all day," Jackie says. "It was an incredibly hard putt. For some reason, the six inches he had left looked like five feet to me. After he marked his ball so Sandy Lyle [Jack's playing partner] could putt out, I reminded him one last time, 'Keep your head still.' Dad smiled and said, 'I think I can handle this one.' And he rapped it in."

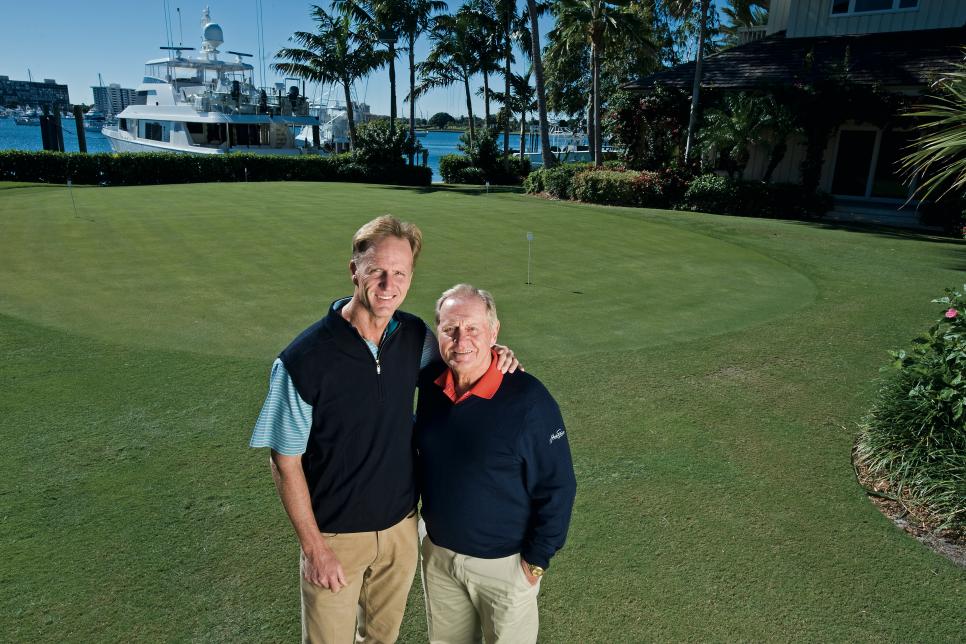

Dom Furore

What happened next made it impossible for CBS announcer Pat Summerall to speak, and colleague Ken Venturi was able to exclaim only, "Ah, beautiful" before choking up. Jack and Jackie embraced and then walked off the green, arms draped over each other. "I'm not a big huggy person, but I am with my kids," says Jack, his eyes misting as he watches the scene on TV. The scene does not elicit poetry; it is not the Nicklaus way. But there is power and emotion when he says, simply, "Jackie and I were both elated at what happened. He's my son. He was with me. That alone was more exciting than the tournament."

THE AGONY OF WAITING

The Nicklauses made their way to the Jones Cabin—Jackie bringing the bag with him—to watch the final four groups. The wait was not easy. First they watched Ballesteros fade when he three-putted the 17th to fall two shots behind. Kite, only one back, hit a fine 6-iron shot to within 10 feet at the 18th but missed. The only player left with a chance was Norman, who had made four consecutive birdies to tie Nicklaus at nine under par. After Norman creased the fairway with a big drive at the 18th, Nicklaus took what action he could.

"I was sitting on a couch, watching Norman make birdies, and I thought, This isn't working very well," Jack says.

"So I stood up. I'm superstitious."

Norman is seen flaring his approach far right, deep into the gallery. It's not the first time Jack has seen it; he caught a replay of the shot soon after that Masters ended. "A few months later Greg led the British Open at Turnberry after three rounds. I found him that Saturday night. I said, 'Remember the swing you made at the last hole at Augusta, and the position you put yourself in? When you come down the stretch tomorrow, don't put the club in that position again.' Greg won the next day. I don't know if my advice helped him, but I did want to pass it along."

Norman followed with a mediocre chip to 10 feet. He missed the putt, and Nicklaus officially had won his sixth Masters. "It was kind of a blur after that," Jack says. "By the time I finished with the press it was dark, and then I had dinner at the club. It was very late when I got back to the house."

The TV broadcast segues to the green-jacket ceremony. Augusta National chairman Hord Hardin congratulates Sam Randolph as low amateur before soliciting comments from Nicklaus. Then Bernhard Langer, the defending champion, helps Jack into his green jacket. The tape ends, and the Nicklaus living room falls silent. There is only one last question for Jack and Jackie Nicklaus, an obvious one: What did winning that Masters mean to them? Says Jackie, "As it relates to Dad on the golf course, that Masters was No. 1.

I'm asked about it frequently, and all I say is, it was awfully special. And I had the best seat in the house."

And Jack? "Several things about that Masters were unique," he says. "My mother had not been to the Masters since my first one in 1959, and she'd said, 'I want to go to the Masters one more time.' So she was there, and so was my sister, Marilyn, who had never been to the Masters. Other family members were there, and a bunch of my friends. At that point in my career, I wasn't having much success. I didn't expect to win, the press didn't expect me to win, the players didn't expect me to win. But my talents were still there, my skills. It was a question of whether I could corral them, keep them in my head, keep myself organized and under control. That was the issue. As I got closer and closer as the round went on, it became more difficult. I did it, and that's what I'm most proud of. And having Jackie there to support me, that was just neat."