News

Buried Treasure

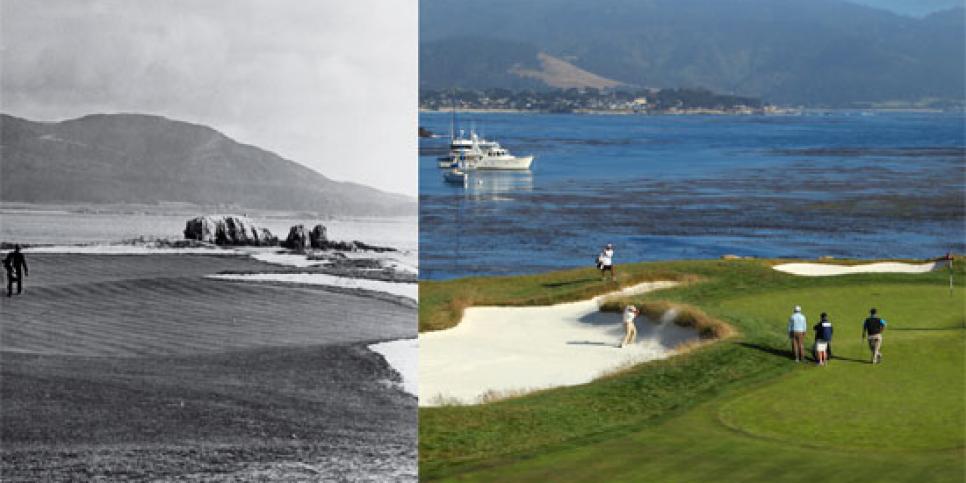

Target Practices: Several of Pebble Beach GL's greens have been upgraded over the years, but some say a more planned, aggressive approach is needed.

The Mona Lisa of American golf might not have a mustache, but she has several whiskers in need of waxing.

Pebble Beach's 2010 U.S. Open exposed a few too many architectural quirks that adversely affected the 91-year-old course's ability to produce a satisfying conclusion: swollen bunker faces encroaching on putting surfaces, shifting mowing lines that have shrunken already tiny greens to untenable sizes and a well-intended but clunky overreaction to technology via strategy-squashing new fairway bunkers.

The resulting design transmogrification introduced too much chance and defensiveness into the U.S. Open rotation's centerpiece course, yet fixing the issues is far from a simple matter.

At a typical classic course, solving similar green complex issues would be straightforward: break out the historic photographs, analyze what would best restore the primary shot values and rebuild the greens. With a masterpiece of Pebble Beach's importance, high-tech mapping could retain the primary contours and allow for the installation of subsurface goodies to help out the superintendent. But Pebble Beach is no typical classic course.

With 70,000 rounds annually since the late 1970s, the combination of explosion shots and wind-blown sand has dilated bunker faces as much as five feet above some greens. Such gradual build-up pushes these wave-like artifices toward the putting surfaces, creates abrupt downslopes and eliminates hole locations that best highlight the design's strategic charm. Furthermore, as with any golf facility, daily mowing quietly changes green boundaries by rounding out the surfaces and stripping away even more design intricacy. This one-two combination has simplified several once-nuanced Pebble Beach holes and turned the formerly grand 14th and 17th into veritable freak shows.

Throw in modern green speeds that eliminate certain sloped areas from the hole-location equation, and the pinnable square footage is as small as 1,400 square feet on the diabolical 14th green. That now-infamous par 5 played as the third toughest hole. Last week, its 5.437 scoring average included 50 scores of double bogey or higher.

"It became more of a story than we would have preferred," said Mike Davis, the USGA's senior director of rules and competitions, who conceded after the final round that he erred in surrounding the diabolical green with tight-mown turf instead of rough. "I don't think anyone on our side enjoyed watching [the golfers] play ping-pong."

Even more telling was player disdain for the green at the 208-yard 17th, which played as the toughest hole all week and averaged 3.487. The hourglass-shaped surface has become harder to hit with each U.S. Open, even though contestants have shifted from 1- and 2-irons in 1972, to 4- and 5-irons this year. Just 18.6 percent of 2010 U.S. Open tee shots hit the green in regulation, with a measly seven GIRs (8 percent of the field) during Sunday's final round. No player in the final four groups hit the green, and to put the 17th's average of 18.6 percent in perspective, the next hardest green to hit was the 202-yard par-3 12th, at 35.8 percent.

"It's a tiny, tiny little bowl thing," Tom Watson said after making the cut and declaring 17 "much smaller" than the teensy Postage Stamp at Royal Troon. "You land it short, you hit it on the downslope, and it goes right on over the bowl. It's as tough a shot as you want. Just to get it on the surface there is a major achievement."

Even the man setting up the course was unable to defend the 17th. "It's a hard argument when you go left with the hole [location] there, and it's firm," said Davis. "It's almost ridiculous."

Virtually every putting surface has seen significant loss of the more nuanced hole locations as envisioned by Chandler Egan in his 1928 redesign. (The eighth and 13th greens were Alister MacKenzie visions retained by Egan.) Such concentrated targets expose the turf to an unusually high amount of traffic, posing agronomic and strategic constraints that no doubt contributed to the bumpiness complained about by Tiger Woods after round one, and more cryptically by Phil Mickelson after Sunday play.

"I wish the greens were bigger," said Davis, who savors setting up Pebble Beach. "It's such a hard test of golf and given 70,000 rounds of golf, you'd like to think of ways to get more square footage. It's not just a U.S. Open problem, but also a day-to-day issue. That said, it's one thing to tell course [owners] to put in a new tee or to change some fairway contours. We would never tell them to rebuild their greens."

So why doesn't the Pebble Beach Company review its extensive collection of historic photographs, rebuild the greens to USGA specs, throw in a little technology to help control subsurface temperatures and reopen the course after nine months?

Because an entire local economy relies on Pebble Beach's 18 greens, not to mention the ownership group attempting to service debts by sharing an iconic course with as many paying golfers as possible. When your course charges nearly $500 for a round, supports several hotels and fuels an economy wrapped around golf trips at nearby Spyglass Hill and Spanish Bay, the $4 million-to-$5 million expense of greens reconstruction is a fraction of the potential financial impact.

According to Paul Spengler, Pebble Beach's executive vice president, the resort has been on an as-needed green-rebuilding program during the past two decades. Seven greens now enjoy the benefits of a subsurface drainage system and in the case of four, a SubAir soil profile assistance system. However, undertaking a more practical one-time restoration would ensure consistent materials, grassing and architectural intent -- but also require the course's shutdown.

There is also the delicate issue of who supervises the work. Pebble Beach investor Arnold Palmer has been overseeing changes to the course since 2000. Palmer makes occasional visits and details his thoughts to the Arnold Palmer Design Company staff in Florida, who then draw up plans for new bunkers that are sent to Pebble Beach for execution.

The remote process, not surprisingly, resulted in several poorly scaled bunkers and has done little to enhance what Jack Nicklaus once called the most strategic course in the world. Palmer repeatedly uses the word "force" to describe how he hopes to make players drive into certain spots, nearly always to put a longer iron in their hands to compensate for modern distance gains. The ensuing loss of freedom, in vivid form at the 2010 Open where defensive golf ultimately won out, is incongruous with the essence of Pebble Beach.

Restoring functionality to the greens and brushing up the strategic highlights will require a detailed study of photos and a forensic approach to construction, something that can't be achieved by an office on the other side of the country. As grand a place as Pebble Beach remains, it's time for the Mona Lisa to be primped, preened and rejuvenated. In the spirit of the world renowned Spa at Pebble Beach, that's the golf architectural equivalent of a "silk peel," an "eminence organic facial" and a wax job all in one. Whatever it takes to protect the investment.

Chandler Egan's work ahead of the 1929 U.S. Amateur offered a generous target on 17 (left, Los Angeles Public Library). Heavy traffic and years of maintenance have combined to reshape the hourglass 17th into a penal puzzle (right, Stephen Szurlej).