News

Counting On Mr. Clutch

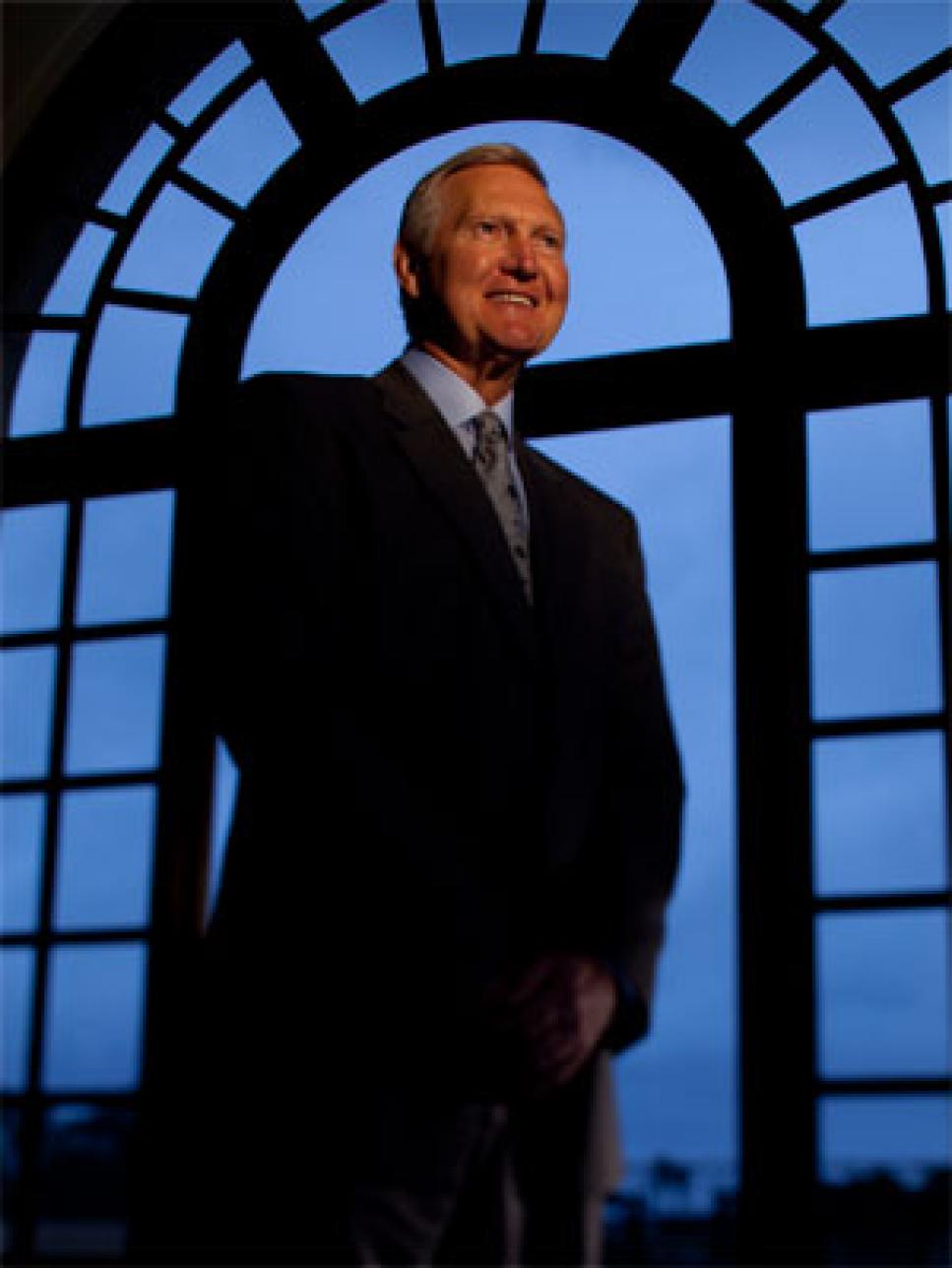

NBA Hall-of-Famer Jerry West is hoping to reinvigorate the Northern Trust Open

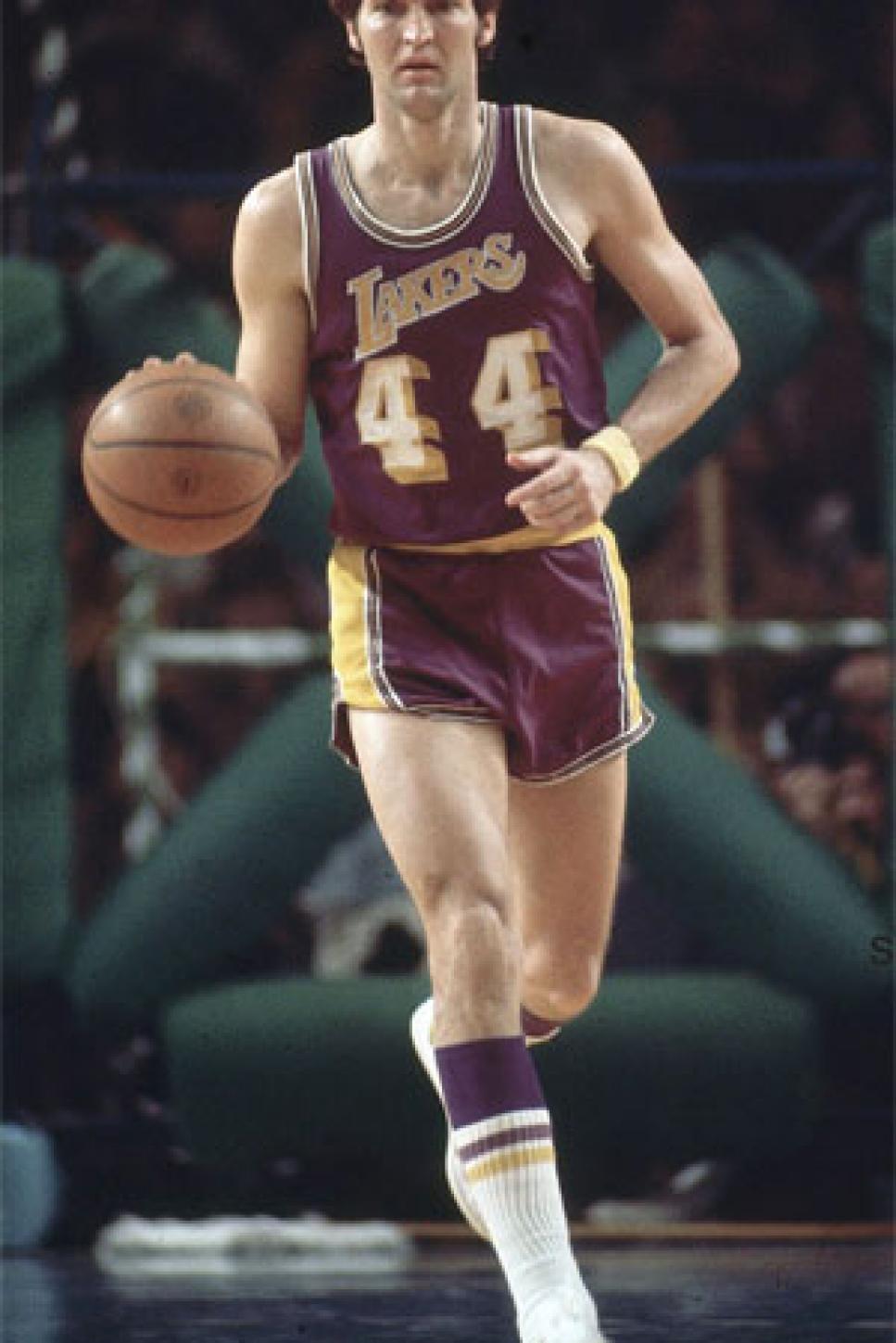

Jerry West is driving to the Conga Room, an aspiring-to-be-hip downtown Los Angeles nightclub where a meeting with Chevron's Glenn Weckerlin awaits. The Conga Room overlooks the new "L.A. Live" development across the street from Staples Center, home of the Lakers, where West's No. 44 jersey hangs in the rafters next to the eight NBA championship banners he helped the team win as both Hall-of-Fame guard and general manager. It's a typical early November day, with comfortable temperatures and a soft sky, perfect for West to play golf or enjoy his Bel-Air home and his passion for reading, perhaps the new Gay Talese book personally inscribed to him.

Since West was named executive director of the Northern Trust Open nine months ago, though, his calendar has been filled with speaking engagements and face-to-face sponsor visits such as this one. Weckerlin is Chevron's affable representative charged with handling sports hospitality. He is hosting media and dignitaries to launch December's Chevron World Challenge, and West is merely stopping in to remind Weckerlin of the mission to rejuvenate February's Northern Trust Open. Because Chevron pours millions into the nearby Sherwood CC-hosted event, it's a longshot bid to sign the oil-and-gas behemoth for even a hospitality package. But West is determined to upgrade the oldest continuously running PGA Tour event's annual charitable donations from about $1 million into something more closely resembling the multi-million dollar contributions tour stops in Phoenix, Dallas and San Antonio have made.

Sporting a meticulously tailored gray suit and unusually erect posture for an ex-athlete, the 71-year-old West Virginia native seems taller than his listed playing-day height of 6-feet-3. After shaking hands with anyone who nods or smiles his way, West pulls Weckerlin aside to better understand Chevron's needs. A few weeks later Weckerlin is asked how the meeting went.

"He's a damned bulldog," Weckerlin says, laughing. "What a first-class guy though. He's on a mission, and he's trying to do something really special."

And West's take?

"I'm not good at asking people to give things, it's hard for me to do," he says, reflecting on his whirlwind schedule of local events designed to expand awareness of the tournament, sign up new sponsors and build the charity-driven fundraising mechanisms modeled after other successful tour events: Tickets FORE Charity and the L.A. Legends Club.

The initiatives are mentioned in West's next downtown stop: a speech to the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. It's the ultimate rubber-chicken lunch, featuring a broad mix of well-dressed business elite who hand out business cards to anyone they don't know. After West is introduced, a few in the audience appear to have little interest in what he has to say, spying looks at their BlackBerrys. But most in the room are transfixed by the man who led West Virginia to its first Final Four, played on the 1960 Olympic gold-medal winning U.S. basketball team, appeared in 14 NBA All-Star games and in 1972 guided the Lakers to their epic 33-game win streak and, ultimately, a world title. Later, as an executive, West crafted the greatest one-two acquisition punch in sports-management history: trading Vlade Divac to Charlotte for the draft pick that was Kobe Bryant and luring free agent Shaquille O'Neal away from the Orlando Magic.

Even the BlackBerry readers take notice as West reflects on growing up poor in rural Cabin Creek, W.Va. That's where, at age 13, he learned of his older brother David's death in the Korean War.

"If ever I could do something for someone like him" said an emotional West, his voice trailing off before collecting himself. "He deserved to live. I was the dumb one in the family."

He asks the 60 or so Chamber members if they have seen the film "October Sky," Jake Gyllenhaal's break-out role based on Homer Hickam's true story of a young West Virginia rocket-builder who dreams of a life beyond the brutal coal country thanks to a teacher encouraging his unique talent for science. "I was a Rocket Boy with a basketball in my hand," West said.

Though West has donated more than $1 million to his alma mater and makes appearances for it during annual three-month summer sojourns home, he also wants to give back to his adopted hometown.

"L.A. has embraced me so much," says West. "It's almost embarrassing how good people are to me."

But a reinvigorated Northern Trust Open is about more than just community. "I tell people that they don't owe anything to this area, but I ask them to consider whether they owe appreciation for having a better life than a lot of people have in other circumstances. That, to me, is important. I go back to my childhood, and I know what it's like to feel sorry for yourself when you see other kids getting to do things and experience things you wish you could have. In L.A. there are so many needy kids, and all they need is the right mentor or the right person to have an interest. We can raise money to help them enjoy opportunities they've never enjoyed."

West lives with his wife, Karen, in a Tudor-style home in Bel-Air. The gated community sits in a sycamore-dotted canyon near the Getty Center and is a 10-minute drive east of Riviera CC. Wearing a white Air Jordan warm-up suit and tennis shoes, West greets a visitor and when he sits down and crosses his legs, reveals NBA-logoed white socks featuring the silhouette of himself dribbling. On his kitchen table are various documents related to the tournament as well as the three books he is currently reading: The Gay Talese Reader, a Chuck Yeager biography and The Last Man On The Moon, astronaut Eugene Cernan's recollections of the Apollo 17 mission.

It was in the same kitchen last May that PGA Tour championship management head David Pillsbury pitched West on the Northern Trust job. Pillsbury explained that he was looking for a way to "activate" a run-down tournament resting on the laurels of its historic host venue -- player-favorite Riviera -- along with a traditional date the week ahead of the WGC-Accenture Match Play. West reiterated that he was enjoying retirement by quenching his "voracious" thirst for books. But he eventually accepted the position after realizing the potential to give back. The Los Angeles Junior Chamber of Commerce remains the primary charitable beneficiary of the Northern Trust Open, but the group no longer has a say in operations. In year one, championship management is already making major upgrades: a bold valet-parking program, a new fan-friendly "Grove" featuring California-accented cuisine, an"outpost" for active and retired military to enjoy complimentary hospitality and West's pet project of more on-course grandstands. Hospitality tents will also be improved, and tournament general manager Mike Bone reports a respectable up-tick in corporate sales thanks in large part to West's hands-on approach with several sponsors. (Chevron is still contemplating a purchase.)

West also dreams of some day livening up early-week tournament festivities, including a possible Tuesday practice-round event and an evening concert arranged by tournament committeeman Irving Azoff (the Eagles manager and Ticketmaster CEO). However, Northern Trust and the PGA Tour want a lower profile this year after Congressional criticism over 2009's hospitality excess, even though Northern Trust never requested TARP funds and specializes in wealth management (including handling of Barack Obama's mortgage and investments). In an effort to ward off critics, Northern Trust even issued a late 2009 press release saying it was reducing its "entertainment budget drastically" at the 2010 event.

amphitheater have framed victories such as Phil Mickelson's last year.

The first year of the new operation faces other hurdles, including a date change and a Super Bowl Sunday finish. With CBS broadcasting the Super Bowl, NBC takes over for 2010. But because of the network's Vancouver Winter Olympics coverage, the Northern Trust flipped dates with the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am. The task to draw new fans has been further complicated by championship management's decision to raise at-the-gate ticket prices by $20 (now $50) in a town notorious for sports fans who make last-minute decisions.

Much of West's desire to see charitable dollars go to after-school programs was motivated by a visit to the Tiger Woods' Learning Center in Anaheim ("One of the most impressive things I've seen in my life," says West). He first met Woods through Bel-Air pro emeritus Eddie Merrins when Tiger was preparing to head for Stanford. And though West will never say it because of his deep admiration for Woods, the world No. 1's sabbatical eliminates inevitable questions about luring the native Californian back to the event that gave him his first sponsor's exemption but which has been left off his schedule since 2006.

West has lobbied other star players. At the Chevron World Challenge he breakfasted with Stewart Cink and Lucas Glover ("really nice, bright guys"), and the reigning British Open champion has entered the event for the first time in three years. West also came away swooning over his visit with Y.E. Yang, who told West he's a huge basketball fan. If Yang enters, West has promised to take the charismatic PGA champion to one of the two Lakers home games during tournament week. Much-hyped rookie Rickie Fowler has received a sponsor's exemption.

The pros he is trying to woo have his utmost respect. "Internally, I think it's the toughest game emotionally," West says. "To be at the very top in other sports, you have to do something very well, but in golf it has to be a little bit of everything: how you approach the game, your ball-striking ability, your short game and the mental aspect -- particularly when you aren't playing well but know you still have to salvage a round."

As for his own golf, West was known for his prodigious length despite typically teeing off with a trusted 2-wood. He received his initial set of clubs -- Wilson Staff irons -- at his first NBA All-Star game. They came with a tour bag featuring his name printed in embarrassingly large type. The bag and clubs sat in his garage "for a year" before teammate Frank Selvy dragged him to a local driving range. West was soon hooked, shooting a 99 his first time around the Chester Washington course on Western Avenue.

Besides working with legendary instructors Jimmy Ballard and Hillcrest CC's Eric Monti, West spent countless hours with Sam Snead, and when the L.A. Open came to town, West camped out on the range, reveling in the technique of all the players, but in particular Snead, Jack Nicklaus, Lee Trevino and Tom Weiskopf.

As his game improved, West's expectations soared. After retiring from the Lakers at 35, he would go to Bel-Air for breakfast, practice for a few hours and then tee it up in a regular game. "A good round just encouraged me to practice more. I was a pretty good copier in terms of watching other people play basketball, yet I couldn't translate that to golf," West says. "And I didn't have the temperament to deal with that."

Ballard concurs, saying West was "as good a putter as I've ever seen" but that a desire to understand his technique ultimately appealed to West more than competitive aspirations. "The golf swing is all about angles, and he's always been fascinated by that and the comparisons to basketball," Ballard says. "One time after a clinic I gave we got into a long discussion about angles. He was even drawing lines in the dirt to show me how little differences in the angles of your defensive position or technique could totally alter the game."

Despite largely giving up golf during his years as a general manager for the Lakers and Memphis Grizzlies, West can get around in the high 70s despite a now-balky putter. He still plays an occasional Wednesday game at Bel-Air CC, where he used to be a scratch golfer and once shot 63. Yet he remains haunted by a sense he'll never be able to play as well as he once did. "It doesn't feel the same, and I certainly don't have the same enthusiasm for it because I know those days are gone," he says.

West is asked if those perfectionist tendencies will so wrap him up in Northern Trust Open duties that he'll be unable to watch, as was the case in 2001 when the Lakers were on the verge of winning an NBA title and he drove his car north toward Santa Barbara with the radio off. A friend finally called to share the news of another championship.

"This is way different," West says. "I don't care who wins. There's another goal, and that goal is to raise money for charity. This is a storied event, and I would hate to see a great golf course like Riviera and great title sponsor look at this and say it's not the success we wanted. Hopefully, I can be part of changing that. If my involvement helps, so be it. If I can't help, I won't be there."