Instruction

The Grit Factor: What It Takes To Succeed + Improve In Golf

I knew Bill Shean at the University of Michigan, where we were caddie-scholars. Bill was the best golfer in the house, mostly self-taught. Blue-eyed and with a big, toothy smile, he reminded me of a Kennedy. He had Kennedy cockiness, too, with the guts to think he could walk on to the Michigan golf team (plus the talent to do it). After school I lost track of Bill. I'd hear once in a while that he'd qualified for the national amateur or mid-amateur, but he never did much in those events. When he describes that period now, he sounds like a finalist in the fourth flight who blew his big chance: "I didn't feel comfortable. I'd get to match play and just choke out of it."

In 1995, at age 52, when most of us are struggling not to lose ground, Shean decided to find out how good he could get. He gave up alcohol.

He gave up caffeine. He took up jogging. And he reconnected with Dr. Bob Rotella, the sport psychologist he'd briefly worked with a decade earlier. Shean was not out to change his swing; he wanted to face up to his collapses under pressure.

This time he completely adopted Rotella's rules: a game plan, written down, stuck to. A pre-shot routine, mental and physical, on every shot. At least 60 percent of all practice sessions devoted to shots of 8-iron or less. No shot, in practice or on the course, ever struck without a goal—target, process or otherwise. In every round, Bill kept a dual scorecard. One number was his score on a hole, and the other was "the number of times I was in the present tense when I hit a shot—I'd write that down," he says.

Beginning in 1998, three years after making this commitment, Bill Shean won three major tournaments: the U.S. Senior Amateur in 1998 and 2000 and the 1999 British Senior Amateur. Several years later, at age 66, he became the oldest club champion in memory at Chicago Golf Club, 11 years older than that year's senior club champion.

Shean should have been an inspiration, but to be honest, I felt mostly envy, because I had the sinking feeling that he had a gear I would never have. He seemed to have not only the ability to define and adhere to an improvement plan, but the capacity to call upon that improvement when it mattered most. A sturdiness of character, revealed both in the improving and the proving.

Educators these days spend a lot of time on this character trait, particularly as it relates to personality development in children. They call it grit.

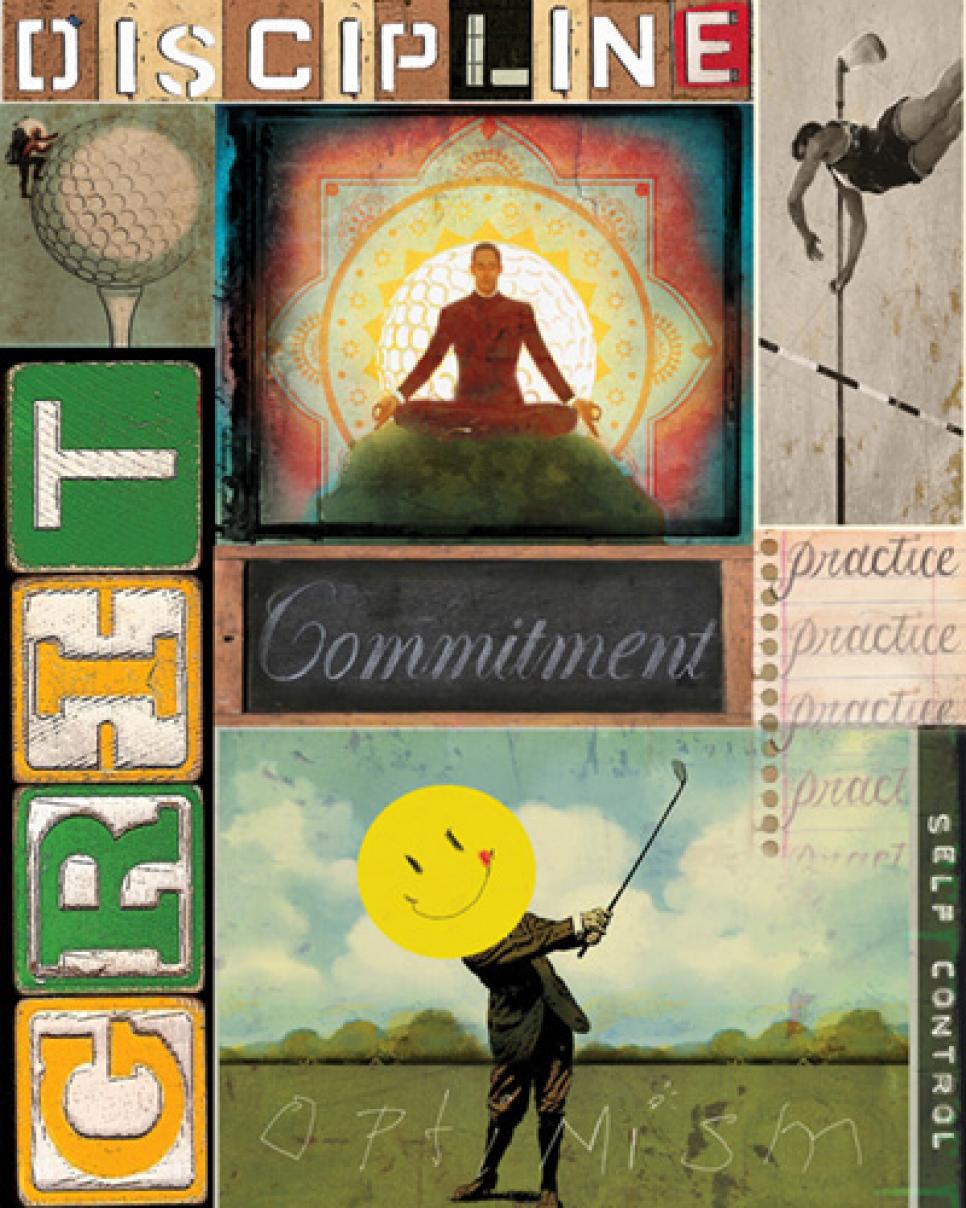

COMMITMENT TO A LONG-TERM GOAL

In an April 2013 TED Talk (Technology, Entertainment and Design) viewed to date 4.8 million times, a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania named Angela Duckworth discussed the foremost predictor of success among Chicago public schoolchildren she'd studied, some in dreadful financial and social situations. "It wasn't talent or brains," she said. "It wasn't social intelligence. It wasn't good looks. It wasn't physical health. It wasn't IQ. It was grit." Duckworth defined grit as "a passion and perseverance for very long-term goals." She explained: "Grit is having stamina. It's living life as a marathon, not a sprint." It includes the kind of commitment Bill Shean showed, seasoned with other traits, like deep-seated optimism, a willingness to delay gratification and, most important, an attitude that sees obstacles as part of learning. Duckworth found the same in teachers and salespeople. I asked her if she thought amateur golfers could develop grit. "If there's motivation, it's never too late," she said. Unlike intelligence, grit is a trait you can acquire. You can learn it.

Before you say, "Duh, everybody knows that," consider your approach to improvement, especially in golf. You want to play better and maybe even dare to think you will. At times you set goals, make a bit of progress but then get distracted. Soon you resign yourself to your place in golf's universe—again. There are guys you can beat, and guys you can't. You have a buddy who'll always contend in the club championship, even if his bad wrist is bothering him, because that's who he is. And you have another buddy, with broad shoulders and a Freddie Couples swing, who'll self-destruct in the first round.

Kids tend to see things that way, too, according to Duckworth and others who are working to identify traits that produce success. Some kids, used to mediocrity and failure, pack it in—at good schools and not-so-good ones. Duckworth and an increasing number of educators now think they can alter that trajectory. There are stunning examples of how schools and dedicated teachers have done it.

This spring PBS aired the Ken Burns documentary "The Address" about the Greenwood School in Vermont. Greenwood is a school for boys with learning disabilities, ADHD being the tip of the iceberg. As the film begins, you meet a class. You learn that in addition to regular schoolwork, each boy has one yearlong assignment: He will study, understand and memorize the Gettysburg Address, then recite it—first to his classmates and then at the formal year-end dinner.

Having been introduced to these kids, it's not possible, you think, not in a million tries.

You're sure this will be the story of how close they came, not of how anyone actually did it. But sure enough, as you follow a handful of them over a period of months, they fight the assignment, push back against teachers and counselors, whine about why they can't do it, why they don't want to do it, why it's hopeless. And then, one by one, they break through. In jackets and ties, they walk to the podium at the year-end assembly and to a room of tearful parents, recite the speech. Perfectly. You think, these are kids climbing Everest. You're watching a miracle.

There are dramatic stories like this in Paul Tough's best-seller How Children Succeed, in which he reports on the movement to teach character—and the science behind it—in New York City's KIPP charter schools (Knowledge Is Power Program)and in inner-city Chicago and elsewhere. Surprisingly, affluent children may be at a disadvantage when it comes to such character-building. Because many parents won't let their kids fail.

"There was always this idea in America that if you worked hard and you showed real grit, you could be successful," says Dominic Randolph, headmaster of a private school that Tough profiled. "Strangely, we've now forgotten that. I worry that these kids get feedback that everything they're doing is great. I think as a result, we're actually setting them up for long-term failure."

"What matters most in a child's development," says Tough, who consulted on this article, "is not how much information we can stuff into her brain in the first few years. It's whether we're able to help her develop a very different set of qualities, including persistence, self-control, curiosity, conscientiousness, grit and self-confidence." The application to golf is so obvious that the editors of Golf Digest worked with Tough over the past year to develop a grit-based golf program.

DISCIPLINE IS THE MASTER INGREDIENT

You can trace the beginning of the teaching-character movement to some marshmallows consumed about 50 years ago. A Stanford psychology professor named Walter Mischel, trying to identify strategies kids used to delay gratification, created the Marshmallow Test, in which he offered 4-year-olds the option of taking one marshmallow as soon as they wanted it after a tester left the room, or two when the tester returned at an undetermined time. Almost accidentally, when Mischel checked back on these kids years later, he discovered that those who had waited at least 15 minutes scored 210 points higher on the SAT than those who took the first marshmallow. The ability to delay self-gratification, Mischel concluded, was a key to academic success.

Mischel's finding was the first ingredient in Duckworth's grit recipe, and it clearly applies to sports. Shean's foregoing alcohol and caffeine, for example, and his commitment to routines at first uncomfortable, set the stage for his improvement. Most golfers want the spoils but don't think about how to become the victor. We're passionate about the game and truly desire to improve, but that's where it ends. When we asked golf instructors and coaches if most golfers are able to make a straightforward initial commitment, the answer came back a resounding "No."

Teacher David Leadbetter says it starts when we're young. "When I first came to this country, I was asked, 'Can you handle the junior program?' Sure, I had done it in South Africa, where the kids rode their bikes for miles to get there. Here, it was like a bloody baby-sitting service. Rich kids moaning about everything." Now, with 20 more years of experience behind him, Leadbetter says, "When a golfer tells me, 'I want to get better,' I say, 'Why don't you define what you want to do? What are you prepared to do to get there?'"

Our willingness, once we set a goal, to practice and work toward it also gets dismal reviews. "It's even true with tour players," says sport psychologist Dick Coop. "Their practice habits when their teacher is not there are nonexistent. Once you leave, they might hit three balls all day with full focus. Hitting balls isn't necessarily practice. Practice should be purposeful. Getting a tan is not practice." Coop calls out one well-known example: "Remember that shot out of the water by Bill Haas at the Tour Championship? [On his way to winning the 2011 FedEx Cup, Haas got up and down from a hazard on the second playoff hole.] I did a little survey of players to see who'd practiced that shot. Gary Player had. Tom Kite had. Most hadn't."

This is all the more discouraging given how tough it is to master even the basic golf shots. Duckworth, a nongolfer, suggested I talk to Florida psychologist Anders Ericsson, who was cited in Malcolm Gladwell's book Outliers for Ericsson's proposition that it takes at least 10,000 hours of practice to master anything. (Gladwell has said he doesn't think the 10,000-hour rule applies to sports but that golf might be an exception.) But Ericsson has studied golf and believes that thousands of hours might not be enough; they must be the right kind of hours.

Practice has to be measured, monitored, evaluated—much like the hours put in by musicians.

Ericsson calls this deliberate practice. Even then, he seems awed by golf's challenge. "One of the most important insights about the game for me is how difficult it is to hit correct shots in a reproducible manner," he wrote. "Even the best mechanical devices, designed for the sole purpose of driving or putting balls, cannot produce completely consistent shots. And neither can the best players!" And that, he says, "makes the search for quick fixes or sudden insights in golf seem unrealistic."

Ericsson's work suggests, and many golf coaches agree, that it's far easier to define and stick to a plan if you're working with a mentor—something few of us do, certainly not long-term. "The fact is, there's too much free information out there now," says instructor Nick Bradley, who has coached Justin Rose and other tour players. "People think they can do it themselves." Even with a teacher, Bradley says, sticking to a plan is challenging. "I was working with one young player—great talent. We devise a plan and begin to work on his putting. He starts rolling it beautifully. First day of competition comes, and he switches to a claw grip and croquet-style putting. He says, 'I thought I'd give this a go today.' "

Among the central characters of Tough's book, Brooklyn intermediate schoolteacher Elizabeth Spiegel stands out. In a world where IQ was thought to be the foremost determinant of chess potential, she has helped Intermediate 318 produce a string of chess champions. But perhaps her bigger contribution has been her tough-love, methodical approach to critiquing their performances. Her coaching has transformed the way these students, many under the poverty level, handle challenges in other parts of their lives. (A documentary called "Brooklyn Castle" tells the moving story of Spiegel's chess champs.)

"With my new students, I try to be as positive as possible, recognize what they did well, and limit the 'areas to work on' to two or three," Spiegel says. "Once someone is an expert—however you define that—they already have confidence, so praise becomes boring. What they need is high-level, insightful criticism. They want someone to look objectively at their performances and tell them what they themselves can't see about how to improve."

Of all the educators in Tough's book, Spiegel is one who has consulted, at least indirectly, in golf. Englishman Nick Hastings, a performance coach with whom 2005 U.S. Open champion Michael Campbell has worked, is a family friend. Spiegel and Hastings have discussed how this kind of training might apply to golf. "It's possible to help performers self-evaluate in more internal ways," Spiegel says. "Instead of judging a performance on just if you won or lost or how many strokes you needed, to rate yourself on intangible qualities like how focused or limber you were in golf, or how creative or thorough or careful you were in chess." It's Bill Shean's scorecard for staying in the present tense.

I was struck by how many good golfers I've met who show that kind of discipline on the course: methodical, repetitive, unhurried, taking care while not being too careful. It also occurred to me, though, that there are lots of bad golfers who seem to operate the same way, displaying conscientiousness but not much else, such as the ability to adjust and adapt, to learn along the way. "Many golfers have learned to look like they're composed," Rotella says, "but inside they're a mess."

Which is why Angela Duckworth added two more traits to her grit recipe, perhaps the most important but least intuitive of the lot: optimism and what educators call a growth mind-set.

OPTIMISM PROVIDES A VISION OF SUCCESS

Martin Seligman, Ph.D., was Duckworth's mentor at Penn. He's famous for determining that optimistic people—teachers, baseball managers, West Point cadets, students, insurance salespeople—are more successful than pessimistic ones. This is true, Seligman found, despite the fact that pessimists are often more accurate than optimists. Being practical can be a serious disadvantage in life. "Success requires persistence, the ability to not give up in the face of failure," Seligman writes in Learned Optimism.

For me, this was the hardest piece of the grit puzzle to grasp. Don't we all know optimistic people who fail over and over? In a time when we rely increasingly on data and can predict so much, how does one dare dream beyond what that data says? What does believing things will turn out right have to do with making them turn out right?

Everything, it seems.

"When we fail at something, we become helpless and depressed, at least momentarily," Seligman says. "Optimists recover from their helplessness immediately. Very soon after failing, they pick themselves up, shrug and start trying again. For them, defeat is a challenge, a mere setback on the road to inevitable victory. They see defeat as temporary and specific, not pervasive. Pessimists wallow in defeat, which they see as permanent and pervasive."

On the 72nd hole of last year's Northwestern Mutual World Challenge, Zach Johnson hit his approach shot into the water fronting the green, seemingly handing the tournament to Tiger Woods. "I got caught up in the moment," Johnson said later. But he gathered himself, miraculously holed his fourth shot from 58 yards, and then won in a playoff. It was something Woods himself might have served up to an opponent.

Six years earlier, in the final round at the 2007 PGA Championship, Woods three-putted the 14th hole for bogey while his nearest pursuer, Woody Austin, was making his third consecutive birdie. Woods' lead, once five, was down to one. What was going through his mind, reporters asked later: "I said to myself, You got yourself into this mess, now earn your way out of it." He did, birdieing the next hole and eventually winning by two strokes.

Ask yourself: Where do you fall on the optimism spectrum? When you fail, do you see it as a personal defeat? (It's me, doing it again.) Do you see it as permanent? (This always happens, always will.) Do you think it's evidence of failure in other parts of your life? Or do you consider it something that happens to everyone at times—and not a pattern for you—and that for the most part, you're successful?

Seligman says this kind of positive self-talk is crucial to success. "I believe that an optimistic explanatory style [the way we explain things] is the key to persistence." He also believes that while an optimistic outlook is innate, we can learn to adopt the habits of optimists. For example, if our natural response to a triple bogey is, Here I go, ruining another round, we can begin to distract ourselves from the adversity and quickly move on: Hey, it's one hole. I'm playing well. Or, like Arnold Palmer famously did, you might blame it on the club you used to hit the disastrous shot and replace it before your next round. It's about building up your defenses and not letting yourself take the fall.

Rotella likes to tell about a Jack Nicklaus appearance at a fundraiser for the Georgia Tech golf program. At one point in his talk, Nicklaus said, "I've never three-putted the last hole of a tournament or missed from inside five feet on the last hole of a tournament." A man in the audience challenged Nicklaus, pointing out that he'd missed a three-footer at the end of a recent senior event. "Sir, you're wrong," Nicklaus said. The man said he had it on tape. He'd send it to Jack. "There's no need to send me anything, sir," Nicklaus said. "I was there. I have never three-putted the last green of a tournament or missed from inside five feet on the last hole." Nick Hastings says this isn't an example of simply being positive. "It's about relevancy." In other words, what's the point of remembering something negative that won't help you going forward? Optimists don't. "It's about your ability to focus and move toward what you want to achieve as opposed to moving away from what you see as failure," Hastings says.

Based on his book, Seligman created a questionnaire to measure an individual's capacity to be optimistic. With the help of New Zealand-based Foresight Learning Systems, Golf Digest had 50 golfers of varying skill levels take Seligman's test. Included in the group were amateurs competing in events of the Long Island (New York) Golf Association and Metropolitan (New York) Golf Association, as well as members of the World Golf Hall of Fame. The major finding of this project was that higher performing players showed superior optimism. The Hall of Fame members tested 17 percent higher than the lowest scorers. More research is needed to conclusively connect optimism to golf performance, but this study clearly indicates that an optimistic style is a predictor of success in golf.

A GROWTH MIND-SET IS THE HIDDEN KEY

Talking to Carol Dweck, a psychology professor at Stanford, is a heartening experience. She conveys the enthusiasm of one who knows she has made a difference. Duckworth, in her work on grit, and Seligman, in his work on optimism, cite Dweck's research. It's at the core of the movement to teach character—and grit.

Dweck found that successful people approach problems as a learning process. While invested in the result, they see it as an opportunity to learn and grow and, therefore, are not afraid of an imperfect result. They view their skills as capable of change. Individuals with a fixed mind-set, on the other hand, see their talent or ability as finite. You're artistic, or you're not. You're good in math, or you're not. You're a great putter, or you're not. If you see yourself this way, Dweck says, any mistake or failure is dreadful.

Dweck's work has had major implications for parenting and teaching. The way we talk to children, she says, tends to foster one mind-set or the other. "You're good in math," is praise from someone with a fixed mind-set and might make students fear future tests that could suggest they aren't so good. "You must have worked very hard to score so well," is more effective praise, leaving room for more risk-taking and discovery. Dweck says the same goes for adults and athletes in the way they talk to themselves and evaluate their talents. A recent article in The New York Times reported on a trend to encourage students to take advanced-placement courses even if they risk failing. The premise was, it's the struggle that teaches, not the grade.

Does this apply to golf? "Absolutely!" Dweck says. "I think a lot of people say there are some who are born natural putters, for example, and some who are not. But many people who look like natural putters have worked very hard to look like that."

People with a fixed mind-set are constantly judging their underlying talent, Dweck says, and think others are judging them, too. "The growth mind-set is not about universal judgment. It says, Here's what I am now, and here's where I'd like to be." Dweck sees it as self-acceptance. "You can be bitterly honest about the decisions you've made, but you're not evaluating your self-worth. You're talking about your performance—big difference."

This is where a lot of golfers get it wrong, according to sport psychologist Gio Valiante, who advises several PGA Tour players. "People get too caught up in their self-concept," he says. "We all have patterns, good and bad. The question is, to what degree are we willing to look at them and potentially alter them."

Dweck tells a story of an aspiring minor-league pitcher who had one very good pitch. "That wasn't going to work in the majors," she said, "but he couldn't bear losing a game and so, never developed the pitches that might have gotten him to the majors."

She agrees that golfers could possess this kind of fragility, given their obsession with score. "Can't they just play with their friends, and take a few risks? If you're defined by score, you can't experiment." Dweck adds: "Do you think you can't improve? Or do you see your weaknesses and feel willing to address them?"

Which reminded me of a story about LPGA Tour player Suzann Pettersen that her former teachers, Lynn Marriott and Pia Nilsson, told me. In April 2007, at the Kraft Nabisco Championship, Pettersen, who had led after 54 holes, was still in front by four strokes with four holes to play. She then double-bogeyed the 15th and 16th holes, bogeyed the 17th, and made par at the birdieable 18th to lose by one stroke. In a conversation with Nilsson and Marriott afterward, Pettersen was frustrated and upset. She had, for all the world to see, choked down the stretch in what could have been her first LPGA major win. "I don't get it," she said. "I didn't do a thing differently, and it just fell apart."

Nilsson begged to differ. "We pointed out that she'd done about 10 things differently on those final holes," Nilsson says, ticking them off: number of practice swings, number of seconds from setup to shot, swing tempo, and so on. "It all changed," Nilsson says. She and Marriott convinced Pettersen that to win under pressure she'd have to consistently do the things she does when she's playing well.

Two months later, she won the McDonald's LPGA Championship, outlasting Hall of Famer Karrie Webb. Though pleased, Pettersen told her teachers that she was far from satisfied. "You guys don't get it. Down the stretch I hit the ball terribly."

Marriott laughed. "No, you don't get it," she told Pettersen. "You just won a major!"

Grit is not about being hard on yourself. And it's less about what you accomplish than what you become on the way. Grit is who you are before it reveals itself in what you do. Psychologist Debbie Crews, who works with the golf teams at Arizona State, puts it perfectly: "Be precedes do. Always. Always. Always."

7 KEYS TO BECOMING A GRITTY GOLFER

Developing grit goes hand in hand with improving your golf game. And just like improving, it's a process. The more you stick to the process, the grittier you get. Follow these tips:

1. Relish every shot. Grit is not about concentrating on "important" shots; it's about staying present for every shot. Consider each an opportunity to learn. Score yourself on whether you were really there, fully focused. This score is more telling than your actual score.

2. Control the talk. It might seem gritty to berate yourself for poor play, but it's anything but. Be realistic, but not critical. Note what went well, acknowledge mistakes, but don't wallow in praise or blame. Move on, and review highlights after the round.

3. Find a mentor. Improving your swing as well as your character on the course is easier when you have a mentor. He or she will help you organize your plan and review progress.

4. Set a major goal. Talk it through with your coach. Break 90? Win the club championship? Be more consistent?

5. Break your goal into smaller ones. Do at least one thing you know you have time for. If shooting better scores means avoiding three-putts, start there. Pick drills for lag putting and making three-footers, and use that learning on the course.

6. Develop a plan. When will you practice? Alone or with your coach? Set a goal for every session, and record results. Challenge yourself. For example, keep going until you've chipped three in a row to within three feet. If creating a pre-shot routine on the course is a goal, what does it include? Did you do it for every shot?

7. Assess your habits. In practice or on the course, what stops you? Frustration? Boredom? Switching goals in the middle? Do you practice only what you're good at? Remember, it's not about blame. It's about re-programming your brain.