News

Mayor Of San Francisco, Lord Of Pebble Beach

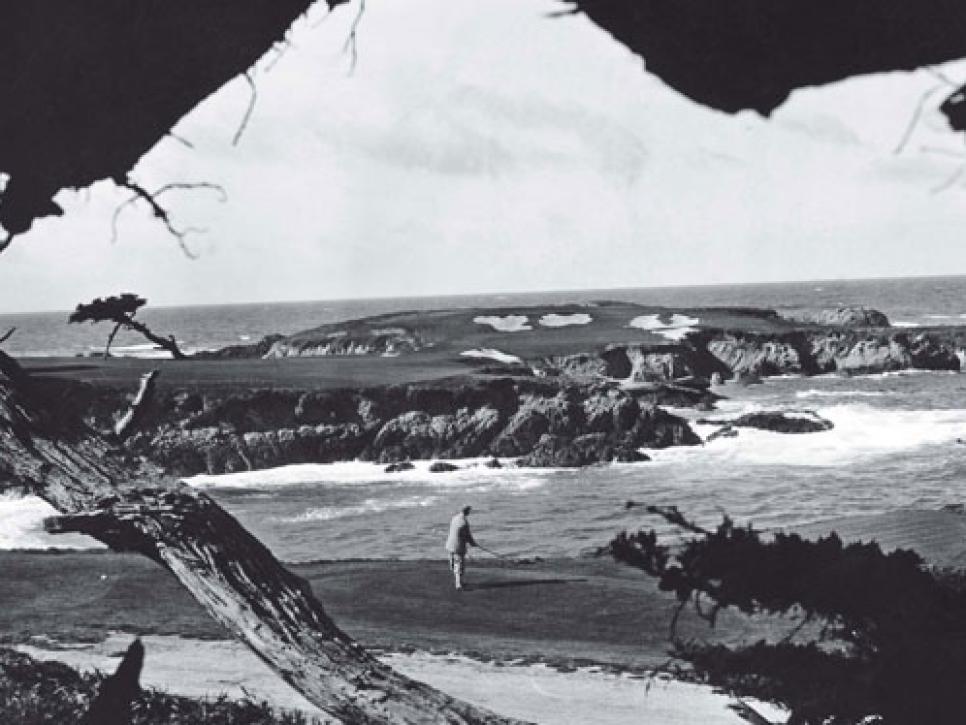

As between the garden of eden and the golf courses on the Monterey Peninsula my father and grandfather didn't make meaningful distinctions, and as a boy growing up in San Francisco in the 1940s I was given to understand that one day I would know why: One day when the war was over, and I was old enough to retain a swing thought and drive the ball to a distance of 200 yards. In the meantime the Japanese Navy was still at large in the South Pacific, my knowledge of the wonders held in escrow at Cypress Point and Pebble Beach limited to the hearsay that my forebears were happy to supply -- deer browsing in the forest, whales basking in the sea, movie stars preserved in alcohol, the lie of the land shaped as if by the hand of Providence.

My grandfather, Roger D. Lapham (1883-1966), had been a founder of the club at Cypress Point in 1927, its president and most devoted member throughout the 1930s. During even the worst years of the Great Depression no two weeks went by without his hopeful presence on the first tee, a vivid and exuberant figure usually dressed in at least four colors of the rainbow, the owner of a still-surviving fleet of steamships willing to play for whatever sum anybody cared to name. The attack on Pearl Harbor remanded the ships to government service, and in 1944 Grandfather, then in his early 60s, his round, red face and shock of snow-white hair known to every bartender in Chinatown, became mayor of San Francisco. Often to be seen wearing a hand-painted orange or purple tie, he delighted in the expression of vivid opinions suitable for framing as a morning headline.

away in 1930 as his grandfather watches.

My father, Lewis A. Lapham (1909-'95), a man of markedly different temperament and character, also had been present at the creation of Cypress Point, enlisted at the age of 18 in 1927 by Dr. Alister Mackenzie, the designer of the course, to drive golf balls into various undifferentiated wastes of grass and sand to mark the points at which to begin a fairway, extend a bunker, route the approach to a not yet fully imagined green. As accomplished a golfer as my grandfather, my father's playing of the course likewise had been interdicted by the war. A reporter and columnist for the San Francisco Examiner in the early '30s, afterward inducted into the family shipping business, he was recruited by the U.S. Army in 1942 to manage the transport of munitions to the hazards all too clearly marked on the beaches at Guadalcanal.

THE WAGER

It wasn't until the spring of 1946 that both gentlemen were at liberty to arrange a rite of passage to the Monterey Peninsula, and on the drive south, as was to be expected from the mayor, he proposed "some sort of wager" to add an element of drama to the proceedings. Gambling was his passion, on a golf course and at the bridge table, where he deemed it unsporting to look at his cards before announcing a bid. The approach to the game sometimes presented the difficulty of finding a partner on the premises of the Pacific Union Club but ensured its being played for what he regarded as a properly courageous stake. Within 20 minutes of leaving the city he suggested odds of 10-to-1: $50 if I broke 100 against $5 (a month's allowance) if I did not; strict USGA rules, no putts conceded, the scorecard to be attested by Frank Archdeacon, the caddie better known as "Turk" in whom my grandfather reposed the trust that other men assigned to J.P. Morgan or the pope. My father advised against the proposition. A sucker bet, he said, and one that I was sure to lose before I reached the last three ocean holes and the sardonic barking of the sea lions on the rocks at No. 17. Yes, in San Francisco once or twice I had posted scores in the high 80s, but not at Cypress Point, not as a boy of 11 uninitiated into the mysteries of ice plant. My grandfather waved away the word of caution as if striking at a fly. How else was I supposed to learn the game if not as moral allegory, a pilgrim's progress meant to try the spirit and search the soul.

Allowing me the time it would take to reach Gilroy to accept or refuse the bet, the ancestors turned to the formalities of a history lesson. The courses at Cypress Point and Pebble Beach owed their existence to Samuel F.B. Morse, descendant of the inventor of Morse Code who in 1919 had obtained the whole of the 7,000-acre Del Monte Forest between Carmel and Pacific Grove, a liquidated asset of the Southern Pacific Railroad. The sale price of $1.3 million brought with it an additional 11,000 acres in the Carmel Valley and the railroad's plans for subdividing the land along the bluffs on Stillwater Cove into narrow residential lots, 50 feet by 100 feet, available to the building of seaside tenements.

Morse burned the plans. He looked upon his new property as the "circle of enchantment" in which he proposed to sell substantial houses to prominent people for important money. Betting that a better class of customer would prefer bigger homes farther up the hillside overlooking both an ocean and a golf course, he engaged two amateur golfers, Jack Neville and Douglas Grant, to compose the national monument at Pebble Beach. The lots on the bluffs were replaced by the incomparable series of holes from No. 6 through No. 10, Neville saying, years later, "It was all there in plain sight."

Morse's designating the result as a public course prompted him to add to his domain the further advantage of a private course, and by 1927 he had persuaded my grandfather, a friend and frequent golf companion, to set up the syndicate that had paid $150,000 for the 170 acres at the southwest tip of Monterey Bay. They undertook to construct 18 holes and a clubhouse for an additional $350,000, the cost to be offset by the offering of 250 memberships at $2,000 each. Dr. Mackenzie, a once-upon-a-time physician who as a major in the British Army during World War I served as a camouflagist hiding gun emplacements on the Western Front, held to the belief that golf architecture was "largely a question of the spirit in which the problem is approached. Does the player look upon it from the 'card and pencil' point of view and condemn anything that has disturbed his steady series of 3s and 4s, or does he approach the question in the 'spirit of adventure' of the true sportsman?"

known as "Turk."

My father was situated at or near the tees eventually to be found at Cypress Point's Nos. 2, 8, 12, 16 and 17, and over a period of four days two caddies measured the distance of the longer drives, Mackenzie shifting the angle 10, 15 yards right, left, forward or back, refining his estimates of a "heroic carry."

Roger Lapham found in Mackenzie's design the imprint of a kindred soul. The presence of the Pacific Ocean between tee and green at the 16th he regarded as the chance to play a noble shot, exposed, as at the bridge table in San Francisco, to a properly courageous loss. Which was the attitude with which Morse and Lapham, men of the same speculative disposition, faced the hazard of the Great Depression. Houses that had cost $1 million to build in 1928 were selling, in 1932, for $50,000, the membership at Cypress Point dwindling to a roster of 33 names, most of them impoverished, but neither Morse nor Lapham gave up their gamble on the dream of paradise regained. Lapham lowered the dues to $10 a month, and Morse forgave the $150,000 debt on the purchase of the property, reserved half the land in his forest as a sanctuary for animals and birds, and saw to it that during the long prayer meeting of Prohibition the Lodge at Pebble Beach never lacked for ample supplies of bonded liquor and Hollywood celebrity. On cold days Grandfather played his round with two bottles of whiskey in the bag: the scotch to drink, the bourbon for warming his hands at the 12th hole, where the course turned back into the wind. Morse refused to sell property, even at double the asking price in 1933, to people whom he judged to be the wrong sort.

My grandfather's remembrances of time past favored the theatrical -- Walter Hagen playing Pebble Beach accompanied by a feminine admirer and a caddie bearing bootleg gin, Bing Crosby at Cypress Point taking 11 strokes to cross a sand dune while humming Christmas carols in a grim and minor key -- and his telling of fantastic tales set up the sting. So apparent was his contempt for caution that I took the wager before reaching Palo Alto, thus rendering unplayable my father's further commentaries on the topic of pride going before a fall.

By nature introspective, his turn of mind formed by his reading of Melville's Moby Dick in contrast to Grandfather's frequent recitations of Kipling's "Gunga Din," my father was disposed to remark on the vanity of human wishes, often with particular reference to a lesson learned from Bobby Jones in the autumn of 1929. Jones had lost his first-round match in that year's U.S. Amateur at Pebble Beach, and when he expressed an interest in playing Cypress Point, a game was arranged with my grandfather, father and Francis Ouimet, who at the age of 20 had won the 1913 U.S. Open at Brookline in a playoff against the British Open champions Harry Vardon and Ted Ray. Word of the match attracted a large gallery, and the sight of it on the first tee reduced my father to a trembling state of nerves. On the fourth hole Jones restored his confidence with a gesture remembered fondly by my father for its saving grace. He had managed to hit his approach shot onto the green, and Jones, his ball lying at about the same distance away, walked across the fairway to ask, loudly enough to carry the question into the gallery, what club my father had chosen to hit. Jones then asked his caddie for the same club. For the next three holes, always in a voice meant to be heard as that of a player sorely in need of advice, Jones made a point of asking my father to select a club or read the line of a putt. The courteous gesture encouraged my father to recover the timing and balance of his swing, Jones meanwhile becoming so taken with Mackenzie's design of the course that in 1931 he employed the doctor's providential hand to shape the lie of the land of Augusta National.

LISTENING TO THE CADDIE

My memory plays tricks with the playing of that first round in April 1946, and I cannot now remember whether the sky was blue or gray, the fog thick upon the ground or lifted by the sun into a thin and silver mist. Wearing a bright red sweater, white flannel plus fours and checkered socks, my grandfather was so eager to swing at the ball that he sometimes turned through a circle of nearly 360 degrees. My father was the more subtle figure in gray corduroy and a tweed cap, taller than the mayor and more graceful in his movements, so deft in his touch around the greens that from any distance under 70 yards he was usually down in two.

On the first tee Turk Archdeacon removed the driver from my hand before I had a chance to swing it. "Not a club that we'll be needing," he said, "not if we mean to win the mayor's money." Attentive to his slightest word, I played for even 5s, hitting a 3-wood off the tees, aiming the shorter iron shots at the front of the greens, recovering from the heavy rough with no club other than a sand wedge. At the par-5 fifth the ball that I'd played into a stand of pine trees bounced mercifully back onto the fairway; at the par-4 ninth I was lucky to sink a long downhill putt that otherwise would have disappeared into a tuft of elephant grass; at the 13th a mis-hit bunker shot stopped a foot short of the ice plant behind the green, and at the short 15th I chipped in for a birdie.

My father and Grandfather refrained from the passing of comment or the making of extraneous remarks. The game was to be approached with reverence, its traditions royal and ancient somehow joining the philosophy of the Greek and Roman stoics with the triumphs of the 19th-century British empire. Golf was unjust; so was death and shipwreck, the game deaf to special pleadings, as indifferent as the sky at noon to the joy of sparrows or the misery of crows. Play the shot and accept the consequences, play the shot and know thyself for a bragging scoundrel or a Christian gentleman. Together with two triple bogeys I managed four pars, but I lost only one ball, and the score of 97 was good enough to win the $50. My grandfather chided me for going the long way around to the 16th green, but when he insisted that the club steward pour a double scotch for "my grandson, the artful dodger," I understood that I had been found deserving of the family name.

REVISTING MEMORIES Sixty-four years have passed, my recollection of that April afternoon overseeded with other memories of further tryings of the spirit on the pilgrim roads at Cypress Point and Pebble Beach. The more famous course I haven't had occasion to play as often, in part because the tee times have become harder to arrange but also because it presents fewer chances to play a heroic shot. The lie of the land, however, is lovelier than it is at Cypress Point, and when I play the holes strung along the shore of Carmel Bay I think of them as the proceeds of Morse's winning bet on the circle of enchantment. He died at the age of 83 in 1969, four years after I last saw him with a drink in his hand in the vicinity of the 18th green, high-handed and autocratic, looking west at the Pacific Ocean with the air of its benevolent proprietor.

Morse never tired of saying that his preservations of nature would move property values nowhere but up, and so it has come to pass. The forest that he acquired for $1.3 million in 1919 was sold after his death -- to Twentieth Century Fox in 1978, to a syndicate of Japanese banks in 1992, most recently for $820 million in 1999 to a consortium of investors assembled by Arnold Palmer and Clint Eastwood -- but the setting remains as it was in 1919, "all there in plain sight," deer browsing in the forest, movie stars preserved in alcohol, whales basking in the sea.

By 1965 I was a visitor from the East. The Second World War put an end to the family shipping business, all but two of its 50 ships sunk by German U-boats in the North Atlantic. In 1948 my father moved his family to New York City, where he soon became a banker and a chairman of the Tournament Policy Board that set up the founding precepts of the PGA Tour. But at least once a year for the better part of half a century he staged some sort of return to Cypress Point, joined whenever possible by his two sons, my younger brother, Anthony, becoming familiar with the name of every bird to be seen by land or sea. We played rounds in the morning and the afternoon, sometimes with my Uncle Roger, sometimes with cousins both near and distant, but in all the years since Turk Archdeacon removed the driver from my hand I never failed to see the course as he first showed it to me, as moral allegory and illuminated manuscript, the lessons drawn in grass and wind and sand.

My final round with the mayor I played in the same year that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and I can still see him smiling at his ball buried in the deep bunker in front of the eighth green, offering to bet that he could hit it to within 10 feet of the flagstick. His opponent, a card-and-pencil sort of man already counting himself a certain winner of the hole, refused the bet because he had watched the mayor make too many heroic recoveries from the sloughs of despond, and he didn't wish to tempt fate to the performance of a miracle.

Fate had already been bargained with, Roger Lapham in the early 1950s having placed the wager against a genuinely irreparable loss with the building of a house 100 yards to the right of the first fairway. It had occurred to him that when no more miracles were left in his bag, his cremated ashes could be interred at the distance of a short pitch shot from the opening hole in Heaven. He died in 1966 at the age of 82, and there his mortal remains remain, entrusted to a cocktail shaker instead of an urn.

Lewis H. Lapham,* formerly the editor* of Harper's magazine, *is the founder and editor of *Lapham's Quarterly.