The Year of Living Dangerously

Tiger Woods was getting better.

Sure, he was only fulfilling a corporate obligation with 24 people who had won a day of golf with him through an equipment-company promotion. But as he stood on the practice tee at a Florida resort before his small audience, perfectionism overpowered perfunctory.

He took the participants through his precise thought pattern in a step-by-step talk-through of his pre-shot routine. He demonstrated in detail his unifying principle of the last four years: Hank Haney's theory of parallel swing planes. He displayed his trademark twirl on shots he particularly liked, along with the lost-in-flow expression. "I want you to actually get something out of this, OK?" he implored at one point. He didn't have to add, "Like I am."

Later, in the banquet room for a closing 45-minute question-and-answer period, Woods chose to use some intimate details from his guarded life as an example of how every experience is an opportunity. When asked to identify the most important thing he had learned about golf in 2007, Woods paused for several seconds, murmured, "Great question," and, in an even voice, opened up.

"Not necessarily golf-wise, but life-wise, I think I've grown quite a bit this year," he said. "After my dad passed last year [Earl Woods died at age 74, after a long battle with cancer, on May 3, 2006], I played well, but I was still not really feeling all that great about life in general."

As the audience leaned in, Woods didn't pull back.

"I felt like I hadn't really appreciated having Dad around. I didn't talk to him as much as I should have. I didn't call him, didn't see him, wasn't there enough. It was kind of in my mind through the entire last year and even the beginning of this year. That I didn't do enough."

As the words filled the big room, there was only stillness.

"But when I had [daughter] Sam this year, I wanted to take in every moment and appreciate everything. And I think that's where my life has changed off the course. And no doubt I played better as a result. But it's sad. One thing I regret is that it took the fact of my dad's passing for me to appreciate how good my life was with him. I wish I had been able to realize how good it was when he was there."

Growth.

The candor, the realness, for a moment, turned Woods into every son who ever lost a father and wrestled with the complicated aftermath. It was an intimate mea culpa one could barely see Woods delivering to close friends on his yacht, "Privacy," let alone in a generic setting with people he might never meet again. But the person who at 20 proclaimed, "I am Tiger Woods" so confidently had clearly, at 31, been giving a lot of thought to just exactly who he wants that to be. And the answers he came up with put him on the most assuredly self-determining path of his life.

When Woods began the year, it seemed that any inner turmoil from his father's death had been left on the 18th green at Hoylake. After all, he'd followed his emotional victory at that British Open with another at the PGA Championship, closing 2006 with six straight official PGA Tour victories.

When Woods made it seven in a row at Torrey Pines last January, questions about missing Earl Woods stopped, replaced by inquiries about Byron Nelson's record winning streak and the impending birth of Woods' first child.

But those in the inner circle knew the impact of Earl's death lingered. They found Tiger distant and less patient. It turned out the tears of Hoylake were much more a beginning than an end.

"There was a sense of loneliness about Tiger that didn't go away for a long time," says Steve Williams, the caddie and friend Woods embraced at Hoylake. "He had more mood swings. I'm a pretty hard-nosed person who doesn't take anything off anybody, and I consider it my professional obligation to bring anything I think will help Tiger to his attention. But for a while after Earl's death, I didn't speak up as loudly as I normally would. There are times in people's lives when you have to be more understanding."

"Tiger is human," says Haney. "He's so good, there's an illusion that he can be fixed like a machine. Just adjust his golf swing, and everything will be all right. Competitive golf is more than the golf swing. It's a million things."

As Woods' focus eroded, his golf lost its sharpness. The loose play became particularly conspicuous at the Masters. Starting one stroke back on Sunday, a start-and-stop 72 wasn't enough against Zach Johnson's 69, as Woods lost by two.

Though Tiger takes pride in hiding "tells" from everyone -- competitors and family -- even he couldn't completely hide his emotions. After playing the Wachovia Championship pro-am in May with close friend Michael Jordan, who has said his father's death in 1993 led to his first retirement from basketball, Woods told The Charlotte Observer's Ron Green Jr. that he spent the wee hours of the following morning staring at the hotel-room clock as he marked to the minute the one-year anniversary of Earl's death. "It was a tough time," he said, later adding: "I just wish I could talk to him, hear his voice and ask him for advice on certain things. Basically he was my best friend."

Though Woods won the tournament, his struggle down the stretch is what prompted Rory Sabbatini to call Woods "more beatable than ever" and add, "I like the new Tiger." After indifferent golf at the Players and the Memorial, Woods produced often-brilliant ballstriking at the U.S. Open, but he came up lacking again. Another closing 72 -- on Father's Day, and the day before his wife, Elin, gave birth after a difficult pregnancy -- was only good enough for second.

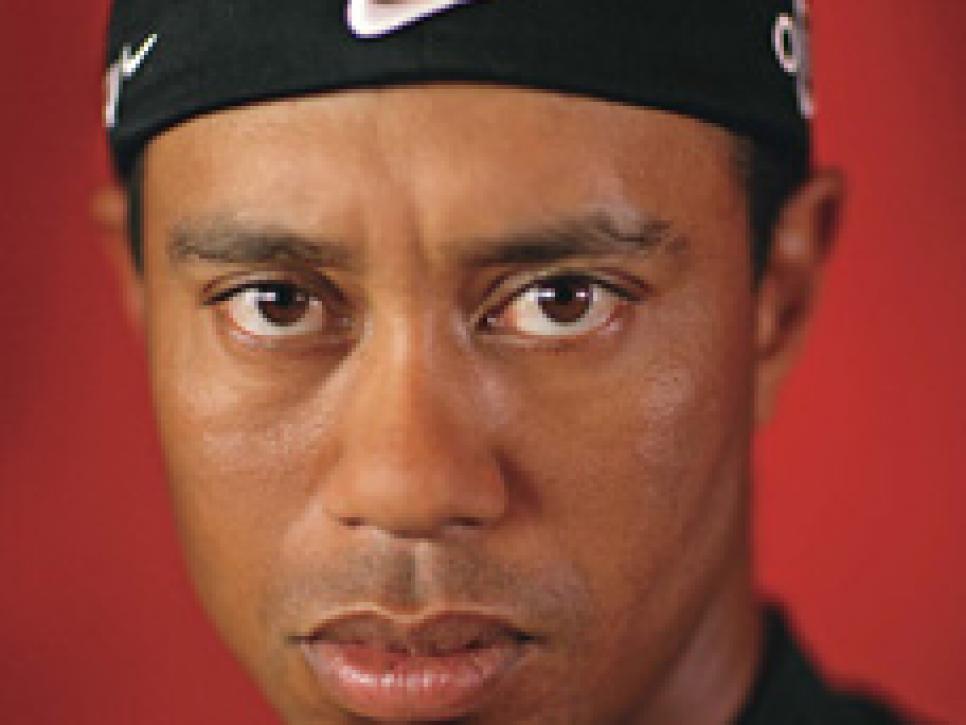

Photo By Walter Iooss Jr.

After the British Open, where Woods tied for 12th at Carnoustie in a week in which his mood was particularly dark, it appeared the year that had begun with so much promise would be a washout in the category that matters most: the majors.

As always with Woods, theories abounded. Some wondered if his obligations as a course designer were a burden. Lackluster play at the Memorial was blamed on a Wednesday arrival caused by attending the press conference announcing that he would be the host of the newly created AT&T National.

Many observers believed that Woods had grown wearier than ever of the constant scrutiny and criticism that accompanies his station. "I get no fulfillment from fame," he says. "I'd much rather have anonymity but still go out and kick everybody's butt. That would be fun. As long as everyone I competed against knew I beat them, and for me to know as well -- that would be enough."

And most intriguing, the new demands of fatherhood. Though eyebrows were raised when Woods didn't travel to Sweden in October to be with his wife and in-laws for Sam's christening (instead, he attended a fund-raiser for his foundation in California), Woods often spoke of his new duties with warmth and humor. "When she wakes up at 2 a.m., I get on the leg-press machine and put her on my lap," he says. "Six hundred reps later, she's out."

But all roads led back to Earl. Haney and others noticed that with increasing frequency Woods cited lessons learned from his father, sometimes adding, "The older I get, the smarter Dad has gotten."

At his Florida outing, when asked who would make up his ideal foursome, Woods' answer was all about longing. "Very simple: It would be a twosome. Just me and my dad," he said. "I wish I could go back and play like we used to play." Woods then told how, to circumvent the Navy Golf Course's minimum-age limit, at age 8 he would carry his clubs through a ditch that bordered the first two holes and meet his father on the third tee. "After nine holes it would be almost dark, and my dad would say, 'If you lose your golf ball, you've got to quit.' So now I've got to call my shot. So I'd call draw, but I'd feel it was a pull/cut. We'd drive down there, and there it would be. We'd play like that until I lost my ball. It really taught you how your swing felt, how to correct it, what impact felt like.

"We used to really compete, and he never let up on me, and I never let up on him. My dad served in the special forces, where if you don't have competitive desire, you die."

EMULATING THE MILITARY MAN

That was just one of many military references Woods made in 2007. More than once, the man whose namesake, Col. (Tiger) Phong, was a battlefield cohort of Earl's, mused that if he hadn't become a golfer, he would have been a soldier. What made his connection to the AT&T National appealing is that it's played in the nation's capital the week of the Fourth of July with active military personnel able to attend for free.

"For as long as I've known him, Tiger's had a huge interest in the military," says Williams. "He always read a lot of military books and watched war documentaries on The History Channel and liked military movies. And when Earl passed away, maybe Tiger thought it was a good thing to indulge in a bit more of what Earl went through."

Woods' initial foray into the soldier's life came in 2004 at a four-day session of skydiving and other combat drills at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where Earl Woods had undergone training before and after tours in Vietnam. This year, more than ever, Woods incorporated hardcore Navy SEAL-style training exercises, like running with a weighted vest, as a regular part of his two-a-days at home. It exceeded the regimen devised by longtime trainer Keith Kleven, who has endeavored to allow Woods the increased intensity while adapting his program to safeguard against injury.

"He checks in with me every week," says Kleven. "He always wants to keep pushing himself, but he's also been listening to my advice."

"We all have our sports activities outside of golf," adds Williams, whose passion is racing stock cars. "I don't think Tiger would do something to hinder his performance in golf."

Emulating a late father is often a powerful force, according to Neil Chethik, author of FatherLoss: How Sons of All Ages Come to Terms with the Deaths of Their Dads. Chethik surveyed more than 300 sons and cited famous examples such as Jordan, who was drawn to a baseball career in part because his father loved the sport and had a wish that Michael play the game professionally.

"Men, especially those who had close relationships, tend to do things that connect them to the memory of their fathers," says Chethik. "They wear their father's old clothes, use their old tools, read their favorite books, listen to their music. It's the natural coping process. A son used to have this man to lean on. Part of the grieving is integrating his father inside himself, so he can still be with him. What Tiger appears to be going through is a healthy process that usually begins to wane in intensity after about 18 months."

Woods seemed to reach resolution in the two weeks after Carnoustie. In that period he spoke with several friends, with an emphasis on listening. "Tiger absorbs and applies better than anyone I've ever met," says his agent, Mark Steinberg. By the time Woods arrived at Firestone for the WGC Bridgestone Invitational, something was different. After an eight-stroke victory, he offered a cryptic explanation: "Yeah, I got more organized."

Completing the healing was the circle of life. When he won the PGA Championship at Southern Hills, it was his 13th major victory in 44 professional starts. But most important to Woods was the fact that his wife and 2-month-old daughter -- dressed in victory red -- were waiting for him on the 72nd green.

"It's a feeling I've never had before," he says. "It used to be my mom and dad. The British Open last year was different, but this one was certainly so special and so right to have Elin and Sam there." It gave further resonance to the generational echo in his daughter's name: Sam was Earl's code name for Tiger when he wanted to get his son's attention without alerting a crowd.

As Woods' life was enlightened, so was his golf. And unlike previous years when he experienced swing epiphanies by pounding balls, this breakthrough came more through quiet contemplation.

"I'll tell you 100 percent what happened," says Williams. "Tiger came back from Carnoustie, and instead of spending hours on the practice field, he just tried to picture how he wanted to swing the club. He used what Hank was telling him to do -- which he had been having quite a bit of difficulty putting into practice -- and went about getting swing thoughts organized and the right mental picture. He came to Firestone having done little actual practice, but from that point on, he had a mental image of himself that he was able to relate to the movement of his body.

"And each week he played, he got a little bit better right up to the Tour Championship. His rhythm and balance with every club were exceptional, and never changed. In the 10 years I've been with him, it was the best stretch I've ever seen Tiger play." That process was how Woods came closer than he has ever been to "owning" his swing, to borrow the phrase that has been his goal since he began working with Haney in early 2004.

"Hank has been invaluable to Tiger, no question," Williams says. "In the last three years he's picked Hank's brain and totally trusted him with his golf swing. But in the maturity process that a golfer goes through, he doesn't want to get too reliant on a coach, because it can cause a loss of feel, and golf is a game of feel. Hank remained his guide, but ultimately it was important for Tiger to find his own way."

It's instructive that after Carnoustie, Woods never visited the range for a post-round practice session the rest of the year. In those final five tournaments, he won four and was second in the other. For his part, Woods said he began to find a groove after discovering that playing in the Scottish wind had led him into an old bad habit: leaning back and squatting too much at address. When he started standing taller and more on the balls of his feet, he stopped fighting his release, and his swing began to flow, helping him lose the high-right-shoulder follow-through that sent the ball wide right. Arron Oberholser labeled the onslaught -- which reached its climax when Woods shot 28 on East Lake's front nine during the second round of the Tour Championship -- "horrifying precision."

Asked for an accounting, Woods described a suddenly unencumbered access to an intuitive genius.

"Just understanding how to play the game," he says. "It's not so much the physical part. It's about playing the golf ball. I was lucky that my dad always stressed to me that golf is not about how far you hit it, but where you want the ball to go. How are you going to get it there? If you don't get it there, what went wrong, so you can apply it to the next one? That's how I play the game of golf. I pick apart a golf course from the green back, factoring pin location, trouble, iron play, then ultimately the drive, and chart my way back from the green.

"It's weird that it happens so quickly now. If we went through the whole process on one hole, it would sound really complicated. But now, I just understand how to deal with it."

OVERCOMING FEAR OF CHANGE

To reach such a pure state, Woods had to transcend the difficulty of taking extensive swing changes into competition, the painstaking process he committed to under Haney even more ambitiously than he once did with Butch Harmon. Perhaps the greatest tribute to Woods' talent is that he has won five majors the past three seasons with a swing that remained a work in progress.

"Tiger is so good that he can find a way to win even when he's uncomfortable with his swing," says Haney. "But he kept getting more and more comfortable with each new move we added and gained more command, which led to the confidence to trust without worrying about the bad shot. He's been at that point in practice rounds for a while now, but it's a whole other mental challenge under the gun."

According to Haney, the biggest hurdle that Woods has had to overcome is "the fear of left." Here's why. The biggest technical change that Woods has made under Haney is altering his takeaway and his downswing so that the club goes back and comes down more in front, rather than more behind his body.

When Woods swung the club more from the inside, he squared the club through the impact area with a last-second rotation of his hands, a "flip" that Woods abhorred for its relative inconsistency. But from the more down-the-line delivery position that Haney taught him, Woods could feel that the flip he was so accustomed to executing would produce a huge pull hook, the last shot he wants to hit. In reaction to this "fear of left," Woods resisted squaring the club, especially the driver, through a combination of leaving the clubface open and lowering his upper body into the hitting area to keep from rotating toward the target. The result was often the block to the right off the tee that has become so familiar in the last few years, along with an angry Woods spitting variations of "Tiger Woods! Trust your swing!"

"What made it so hard for Tiger to change is that he knew he could get away with that shot most of the time," says Haney, describing a style that Jack Nicklaus used to call "playing badly well."

"Tiger knew he could use his management and strength from the rough and his recovery and short-game skills to get the ball around, birdie some par 5s and make a score," says Haney. "What he knew he couldn't do is hit the ball out of play where he could make a big number, which felt more possible by committing to the same swings he could pull off with no pressure in practice. In other words, if he knew he had wiggle room, he would wiggle. Invariably he would hit his best drives on holes where there was no bailout, and he was forced to make his 'good' swing. Gradually, he's had enough success with good swings that the fear is gone. As hard as he works, it still just takes time."

That the time came at precisely the moment Haney had to stop traveling to tournaments was a blurring coincidence. Haney returned to his home in Dallas to attend to his wife's health issues after the first round at Firestone and never attended another event, including the PGA, the first major championship he missed since he began coaching Woods. Naturally, Woods' subsequent success and Haney's absence spurred speculation that the duo had broken up.

It wasn't until November that Woods posted on his website a definitive statement that the partnership remained solid. But the underlying point was that Woods had achieved a self-sufficiency that is the ultimate goal of both student and teacher. "You always have to be able to figure it out," says Woods. "That's something that all my instructors I've ever worked with believed. They can teach you whatever you want, but ultimately you have to pull the trigger. No one can tell you inside the ropes what you're doing wrong; you have to figure it out. And then figure it out on the fly and adjust, and make the change and trust the change, that's the ultimate."

Though Haney has grown weary of criticism of his role -- BBC commentator and former player Jay Townsend, for one, says, "As a huge fan of Tiger, I feel cheated. I just don't think he's done the right thing with his swing under Hank" -- Haney is happy with the new arrangement. Drastically reducing the 120 days a year he was spending on the road with Woods will allow him to devote time to his junior golf academy in Hilton Head Island, as well as spend more time at home. "It's all worked out," he says. "Going forward, the ideal model for me would be the relationship Jack Grout had with Nicklaus. Tiger doesn't need me to watch him hit every ball anymore."

In broad terms, the arc of the Haney/Woods relationship is similar to Tiger's with his father, who once said, "I raised Tiger to leave me."

Of course, in a very real sense, Earl Woods is still around. According to Chethik, men who were close to their fathers often achieve their greatest accomplishments after grieving because of a "liberating peace of mind that adds clarity and resolve." Nicklaus is the best example, reacting to his father's death in 1970 with seven majors in the next six years.

Though Woods has won three majors since Earl's death, it has been the way he played since getting in a better place emotionally that is most intriguing and has fellow players anticipating that, at age 32, he will jump to yet another level in 2008. And as Woods closes in on Nicklaus' record, needing six pro majors to pass Jack's 18, he doesn't see the task becoming more difficult psychologically.

"I don't really think so," he says. "Every time I'm in a situation now down the stretch of a major on a Sunday afternoon, I can always say,* I've done this.* Other guys might not be able to say that. That allows you to play more at ease. Understanding how to win allows you to win more." And as the majors become the only events that truly make a difference in Woods' career, his biggest challenge might be challenge itself.

"Rory popping off was good for him," says Haney. "Phil and Butch working together is good for him."

Most important to his longevity, Woods continues to have fun with a game he has never stopped loving. He seeks practice rounds with Bubba Watson, who entertains Woods with his freakish power and loose-jointed grace. Woods hits a bevy of persimmon-head drivers and fairway woods on the range at Isleworth, saying he loves the sound and feel and the smaller margin for error. "If I ruled golf? We'd be playing persimmon and balata," he says.

The attitude is most evident in his mentoring of 20-year-old aspiring pro Corey Carroll. After being impressed with Carroll's penchant for eight-hour days on the range at Isleworth, Woods introduced himself to Carroll in a practice bunker three years ago, breaking the ice by saying, "What are you trying to do with this bunker shot?" Carroll says, "When I showed him, he said, 'That's interesting. Some guys have had success that way. Here's how I do it.' And for the next two hours we hit bunker shots and talked.

"The context of our friendship is a mutual admiration of work ethic," says Carroll, a self-described "alpha nerd" who attends Rollins College, enjoys building computers and recently missed advancing in the first stage of the tour's qualifying school. "About a year ago Tiger suggested I begin working with Hank, and since then Tiger and I get into a lot of discussions about the mechanical aspects of the game. We practice together and work out together, talk about the methods of different players, just anything golf.

"Usually the first thing he says when he sees me is, 'What are you working on? Let's see a swing.' He knows where I am in my progress, and I know where he is. You might say he's a little farther down the road.

"But as gifted as he is, I know that every piece of swing that works the way he wants it to work, he's had to fight for. He basically tells me, 'You know how to work hard, so you've got the toughest part down. Keep learning and keep grinding. And see how far it will take you.' "

By mentoring to such a degree, Woods might be consciously or unconsciously finding another way to emulate his father. It's all about learning new stuff and seeing how far it will take him.

"I view my life in a way ... I'll explain it to you, OK?" he told his small audience in Florida. "The greatest thing about tomorrow is, I will be better than I am today. And that's how I look at my life. I will be better as a golfer, I will be better as a person, I will be better as a father, I will be a better husband, I will be better as a friend. That's the beauty of tomorrow. There is no such thing as a setback. The lessons I learn today I will apply tomorrow, and I will be better."

In 2007, in more ways than ever, Tiger Woods got better. And few doubt the best is to come.