News

Price Of Success?

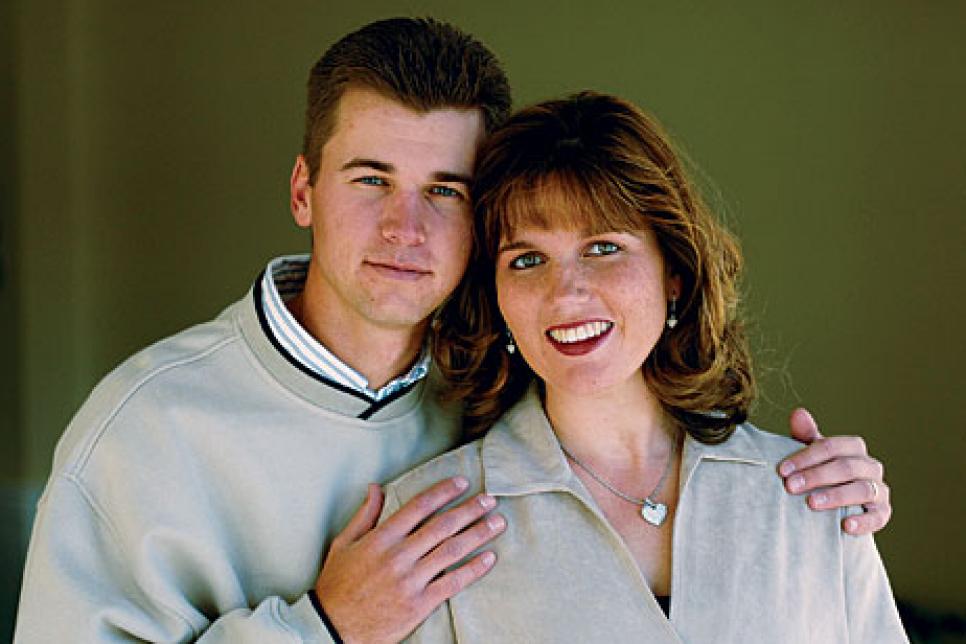

O'Hair, who turned pro at 17, made the cut last week in his first PGA Tour event.

Many pros take some detours to get to the PGA Tour, but 22-year-old Sean O'Hair, who made his rookie debut last week at the Sony Open, describes his journey as downright "twisted."He is not talking about traveling curvy highways, either, although in a grow-up-fast adolescence directed by a domineering dad intent to see his son on tour, he did plenty of that, too.

O'Hair finished in a tie for fourth at qualifying school finals last month to earn his card and stands as the second-youngest player on tour in 2005. Yet the numbers on his birth certificate are belied by those on his internal odometer, given that O'Hair has logged more than 200,000 miles traveling around golf's minor leagues since turning pro after his junior year of high school. Then again, that distance pales compared to the chasm between O'Hair and his father, Marc, whose relationship with his only son is characterized as dysfunctional by some and alarming by others.

Sure, O'Hair made it to the big leagues at an age when top college stars are just getting their spikes dirty as professionals, but at what price? "It's not the happiest of stories, but it's a good ending," Sean says of his six years as a struggling pro. "Somehow, some way, I pulled it off." His PGA Tour career got off to a respectable start as O'Hair made the cut and finished T-72 at the Sony.

Peeling away the layers of the O'Hair saga is golf's equivalent to skinning an onion: It makes some folks tear up, and the smell lingers. "The reality of it is, it's going to haunt him for a while," says O'Hair's attorney and agent, Michael Troiani, "sort of like Vijay Singh has had to deal with the scorecard issue and John Daly has had to deal with his problems."

O'Hair was one of the nation's top junior players, a star in the American Junior Golf Association, when he turned pro at 17, one calendar year before fellow teens and future PGA Tour card-holders Ty Tryon and Kevin Na. With little, if any, fanfare on Sept. 9, 1999, O'Hair became the first prominent American male in years to turn pro as a high-school student.

As much for his turbulent background as his talent, Sean is no longer under the radar. Marc O'Hair, 52, signed management contracts with his son, says he invested $2 million in his boy's professional future and subjected Sean to a physical and psychological regimen that would make most drill sergeants blush. Sean broke free in 2002 and has not spoken to his father since a perfunctory greeting at Sean's wedding more than two years ago.

For the father who drove his son so hard, the acrimony burns like a knife in the back. "I'm an iron-asshole bastard who made all of his money the hard way, through my own sweat," says Marc, who lives with his wife, Brenda, and 15-year-old daughter, K.D., in Lakeland, Fla. "I invested everything I had in his golf game. I was floored when my flesh and blood, my own son, told me to shove it."

Few others, though, were surprised that push came to shove. The roots of the rancorous tale began when Marc O'Hair sold his stake in the family shutter business in Lubbock, Texas, for $2.75 million and ultimately moved to Florida and enrolled Sean, then 15, at the David Leadbetter Golf Academy in Bradenton, Fla. The father and son quickly distinguished themselves among the school's many prodigies and prospects—not necessarily for the right reasons, however.

"Behind every great kid, there's usually a domineering senior citizen," says Gary Gilchrist, an instructor at the Leadbetter Academy during Sean's tenure. "Good or bad, they always seem to be there. But somewhere, somebody has to draw the line."

Marc O'Hair, a large man who wore dark sunglasses, subjected Sean to a rigorous routine that stood out. He was sometimes brusque to tournament, rules and school officials, event organizers and other parents. His son, by design, was treated as a commodity.

Sean signed his first contract with his dad when he was 17, requiring him to pay his father 10 percent of his professional earnings for life. He signed another when he was 20, Marc says.

"I told him, 'I can't blow this kind of money without a return,' " Marc says. " 'When you make it, there has to be payback someday.' "

Taking a tough-love approach, Marc drove his son hard. While the results speak for themselves, those who watched the duo believe there was madness in the method. As a junior player, Sean was forced to run a mile for making bogeys or finishing over par at tournaments. Marc once claimed he made Sean run eight miles in 93-degree heat after shooting an 80. At a 1998 AJGA tournament in California, Sean shot 79, then spent part of the night logging seven miles on a treadmill, a friend, Christo Greyling, says.

"The next day, he could hardly walk," remembers Greyling, a former AJGA player and a senior at University of Georgia. "We could hardly believe he [Marc] went through with it."

Chan Song, a Georgia Tech senior and former Leadbetter Academy student, used to receive rides from the O'Hairs to junior tournaments. "I remember them being really nice to me," Song says. "Around his dad, Sean was just a little quieter, that's all."

Other players, though, say Marc would berate his son in the presence of others. Dad admits slapping his son, but he says he never injured him. Sean declines to discuss the specifics of his father's behavior, but he missed numerous social activities because he was on the driving range, working out or watching tapes of his swing. "We'd go to the beach, have an outing at Disney, do something social, and he'd be out in the parking lot with his dad doing some crazy crap [drill]," says Erik Compton, who competed in AJGA events with Sean and roomed with him at the 1998 Canon Cup team matches.

In addition to the golf work, Marc awakened his son at 5 a.m., had him run a mile and lift weights. After Sean turned pro, Marc cooked meals on a portable stove in their hotel room so that Sean ate the right foods. Every day was like boot camp, and the military comparisons aren't by accident.

"What am I supposed to do, say, 'Oh, Seany boy, you don't have to get up early today,' " Marc says sarcastically. "The military, they know how to build a champion. Somebody who slacks off, that's a loser. The typical high-school kid is hanging out at the mall—that's a loser. You have to have a goal or you are just wasting time. I busted my [butt] on this thing. I thought I was doing him a favor. You would not believe what I did for him."

Or what Sean did without. "From age 16 to 22, that's your childhood, your memories, when you grow the most," Greyling says. "It was unfair."

On the last hole of the second round of a three-day AJGA event in 1999, AJGA officials recall, O'Hair faced a four-foot putt to finish even for the day. Marc, standing nearby, warned in a voice loud enough to be overheard, "If you shoot over par, we're going home." O'Hair missed the putt, and he did not play in another AJGA event. Sean was on the short list of dozens of Division I schools, but interest waned as coaches became familiar with his family saga.

For the first three years after Sean turned pro, the O'Hairs toured the country in a Ford sedan, with Sean finishing his senior-year requirements in the front seat via correspondence. They put roughly 90,000 miles on the car in a year. On the course, Sean was amassing failures and miles in equal proportion as he attempted to Monday qualify on the Nationwide Tour, where he had no status.

Before long, the pair began drawing attention. CBS's "60 Minutes II" prominently featured the O'Hairs in a 2002 segment entitled "The Tiger Formula," which examined how some decidedly hands-on parents were preparing their kids for a future in the game. Marc O'Hair's opening statement prompted jaws to drop and provided the perfect sound-bite summation to his master plan: "I was in business 20-plus years and I know how to make a profit," he told CBS. "You've got the same old thing—it's material, labor and overhead. He's pretty good labor." It was laborious for Sean, to be sure. "The thing about my dad is that, in his own twisted way, he did the best he could for me," says Sean, who is softspoken and wiry at 6-foot-2, 165 pounds. "But anyone who has the right perspective thinks he's crazy."

On the road from 2000-02, they were essentially inseparable. Dad served as chauffeur, cook and caddie. Sean rarely was able to discuss the mounting tension and sense of isolation. "We have never had a father-son relationship," Sean says. "It has always been the investor and the investment. That's a tough deal when it comes to family. I basically felt like I was thrown to the wolves. Being so close to each other for such a long time, with the stresses we were having, I wasn't making any money at all, and we were putting lots of money into it."

Both initially believed Sean was too talented to play the mini-tour circuit, but the Nationwide route was an unmitigated disaster. Sean earned a paltry $5,844 over parts of four years on the developmental circuit, sometimes getting schooled by players nearly twice his age. The scar tissue was far thicker than the earnings in his wallet.

"Whenever you do something different, and there was no book to go by, you learn some things the hard way," Sean says. "It's not like, well, we screwed up and we will be OK. It's the real world. I wasn't used to struggling, my dad wasn't used to struggling and that's a tough situation. Basically, the welfare of my family was on a 17-year-old's shoulders."

Three years ago Sean was very much down on himself and living with his parents in South Florida. While practicing at a course near his home, he met Jackie Lucas, who played golf for Florida Atlantic University. He'd never been on a date and was painfully shy, according to Jackie. "He was like a robot, sort of," she says." Nonetheless, they immediately hit it off. At the end of a dismal 2002 season, Sean left the O'Hair household. Few were surprised by Sean's emancipation. "If it was a healthy relationship, they wouldn't have had the breakup," Gilchrist says. "If something's healthy, you don't fall sick."

Coincidentally or not, whatever was ailing him on the course was cured soon enough. Though he had earlier tried and rejected the Hooters Tour circuit, Sean reasoned that establishing roots and playing weeklong events on a mini-tour made more sense than trying to play his way into the Nationwide fields, where dozens of more experienced players battle for a handful of available spots. With his personal life more stable, his professional life soon followed.

"As a 17-year-old, having the pressures that he had on him to provide for the family and succeed, and being reminded of it if he didn't was very difficult," says Jackie, who is a year older than Sean. "If you look at what he's done since he started doing what he felt was best for his game, he has taken off from there."

Sean and Jackie got married in late 2002, and with his wife serving as caddie, he blossomed on the New England-based Cleveland Tour, where he had one victory and six other top-three finishes in 10 starts, and the Southwest-based Gateway Tour, where he finished second in the tour championship. He earned $115,860 on the two circuits in 2004, but his pedigree was never far behind. After recording his victory last summer on the Cleveland Tour, he went home and learned that "60 Minutes II" was re-airing his segment. "It's embarrassing that people who I don't see for a long time, that's how they remember me," Sean says. "They know me for what my dad did, and he didn't do a lot of positive things, to say the least."

The cash flow became positive after Sean and Jackie decided to strike out on their own, which was good, since striking out financially was a possibility. Without Marc O'Hair's bankroll, the couple used money they had been given as wedding presents as a stake. They borrowed money from Sean's grand- father to buy a motor home, often sleeping in it to save money while on the Cleveland Tour.

"That was probably the most pressure and the scariest moment for both of us," says Sean, who now lives in Boothwyn, Pa., a Philadelphia suburb. "We had no money in our account, we put everything into the mini-tour and we had no idea how I was going to play, because I had not played very well for a long time."

His odd career template notwithstanding, he managed to secure a PGA Tour card well before most players can fathom such a thing. He's been to Q school six times, advancing through all three stages in 2004, including a birdie-birdie-birdie finish at second stage to earn his first trip to the finals.

"As tough as I had it, and it was a pretty damned tough childhood, I think I have learned a lot from the decision I made," Sean says. "I have learned how to persevere in tough times, I have learned how to be mentally tough. In college, I might have learned some of those things. The route I went, I learned how to be a professional golfer. Was it the right decision? I have no idea. All I know is that I'm 22 years old and I have a PGA Tour card, and I've just started my career."

So, from that standpoint, the O'Hair-raising project has been a success. "If that's all that matters, yes, he's on the tour at age 22," says Steve Dahlby, Sean's swing coach for much of the past 10 years. "But most people would say that's not all that matters."

How the family dynamic develops from here is anybody's guess. No question, dad feels a broiling sense of festering betrayal. In fact, Sean is worried that Marc will someday sue him for repayment of the money spent fostering his career. "I hope I don't have to go through that," he says of a legal battle, "because that's been a bit of a concern." Truth be told, dad has other ideas. Marc says he has placed 25 photocopies of their contracts and a cover letter into envelopes he plans to mail to media outlets when his son makes a splash on tour.

"As soon as he gets famous, I am going to lower the boom," Marc says. "I am going to show everybody what he did to me. I have no intention of suing him. I intend to crucify him in the media, because what he did to me is not right."

Marc is living in a home at Grasslands GCC in Lakeland, which he says "isn't paid for." His wife works for a dermatologist, and Marc says he has less than $500,000 left in his bank account.

"I feel like a damn fool," Marc says. "I thought I would get every penny back."

Troiani, a longtime friend of Jackie's family from the Philadelphia area, is serving as Sean's agent. Jackie's father, Steve, an insurance broker, is caddieing for him. In addition to being embraced by his in-laws, since he parted with his dad Sean has visited uncles and cousins he hadn't seen in years. "Even if Marc never reconciles with the rest of the family, I hope he does with Sean," says Marc's brother, Brant, 49, who runs the family shutter business and says he hasn't spoken with his brother since 1995. "Nobody wants it to end like this."

Despite their history, Sean has avoided taking any public cheap shots and prefers to take the high road. Sean still feels protective of his dad. "This story, and everything I have told you, is not going to be anything positive for him," Sean says. "With everything that has gone on, to be quite honest with you, he feels betrayed in some ways."

In fact, when Sean describes how their relationship soured, his voice is rife with sadness and regret. If he feels any bitterness, it's well-concealed under a veneer of naivete. In many ways, given what he missed, he remains a kid. "He seems old well beyond his years in some ways, but in others, he's not," says Dahlby. "Right now, I'm trying to teach him how to properly tip the waitresses."

He could be flush with folding money soon enough. Marc believes his son is better toughened for the tour rigors than the best NCAA standouts. He all but guarantees that Sean will crack the top 125. "Right now, I will take his experience over the past six years versus the résumé of Bill Haas," the elder O'Hair says, referring to the NCAA's top player last year. "Sean's a seasoned veteran disguised as a rookie."

Mike Moses, head pro at Concord CC in suburban Philadelphia, Sean's home course, believes O'Hair has the game to succeed. "He just hits lasers," Moses says. "You can hear a difference when he hits the ball—there is this distinct 'crack.' "

Over time, dozens of people have told Marc O'Hair he was misguided in how he was trying to create a tour pro, advised him to throttle down the intensity and urged him to give Sean more breathing room. Marc can't resist thumbing his nose a bit, since, after all, it worked. "They'd ask, 'Do you know the odds of Sean making the PGA Tour?' " Marc says. "They would all just laugh at me."

Sean soon will have the chance to be a parent himself. Jackie is due to deliver their first child in February, and Sean hopes someday to have a large boisterous family. "I'd like to have four kids or somewhere thereabouts," he says. "But we're still negotiating on that front."

Meanwhile, as Sean begins his PGATour career, 15-year-old K.D. O'Hair is back in Lakeland with an eye on a future in the theatrical arts. The performance of Sean's little sister in a Christmas play staged last month in her hometown was described as "luminous" in a newspaper review, and she belted out the national anthem at an Orlando Magic basketball game a few weeks ago. Both the U.S. and Canadian anthems, in fact.

"We think she has a chance to be something special," Marc says.