The Loop

What are Tiger Woods' "vulnerabilities," and can he fix them?

Getty Images

Almost since the day he turned pro, Tiger Woods has played and lived in a self-imposed information vacuum. He's famous for how little of substance he says -- and how tightly leashed he keeps those around him.

That vacuum is why revelations about his game (and his personal life) explode with such energy. Nobody knows the details, so everybody guesses, using scraps of information like Jesper Parnevik's "flushing everything" scouting report as a jumping off point.

When Woods announced Monday he was backing out of his entry into this week's Safeway Open, he said it was because of non-specific "vulnerabilities" in his game. If he was "flushing everything," as Parnevik said, what does that mean? Woods insider Notah Begay pegged the withdrawal to vague issues with "in-between shots," which could mean anything from finesse irons to delicate shots around the green -- the ones he struggled to hit after his last comeback.

Since Tiger probably won't say anything else until December, when he's scheduled to play in his own Hero World Challenge, it's all a guess what those vulnerabilities really are -- and everybody from Brandel Chamblee on the Golf Channel to Joe Average on Twitter has one.

He's not ready to play so many consecutive days yet.

He's still very rusty.

He's nervous about putting his game on display.

The chipping issues he had during his last return are back.

He lost prep time to the Ryder Cup and Hurricane Matthew.

The real answer is probably a combination of some or all of those reasons.

Conditioning and rust are the most obvious. Woods hasn't played tournament golf in more than a year after three serious back surgeries. Nobody but Woods and his team knows how traumatic the surgeries were, or what they even entailed. And only he knows when he's physically ready for the grind of a regular practice and playing schedule. Woods' game wasn't in good shape even before he got hurt, which means he had plenty of construction work to do with swing consultant Chris Como after finally getting back on his feet.

The other "vulnerabilities" come with healthy doses of amateur psychoanalysis -- and armchair swing analysis. How does one of the greatest players of all time put a game back on display that certainly won't compare to what he showed during the peak of his powers? What kind of progress -- and results -- will satisfy him? And what setback would be too much of an embarrassment to continue to fight through?

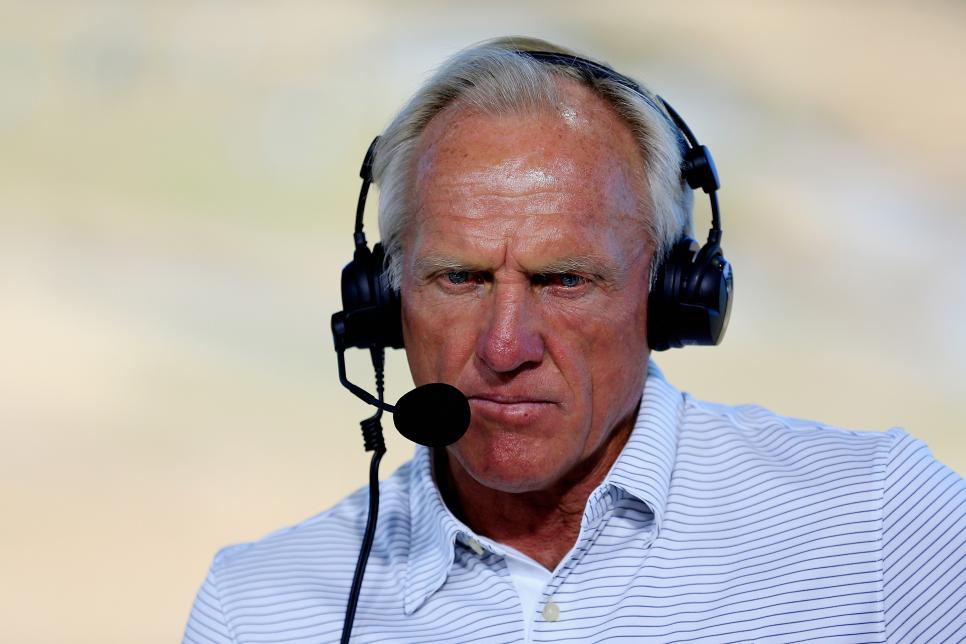

Getty Images

Greg Norman knows about the stresses that come with re-emerging on the tournament scene. He hadn't played in a major for three years before the 2008 British Open, where he would hold the lead after the third round and end up tying for third. After that tournament, he essentially stopped playing tournament golf because he saw that he couldn't compete at the highest level. He says that Woods' up-close experience at Hazeltine could have at least temporarily discouraged him about his readiness for a comeback.

"When you're someone like Tiger at Hazeltine, you watch Sergio and Phil battling it out and you start asking yourself, 'Would I be able to match a 63 with a 63?'" says Norman. "You start talking to yourself."

Short-game guru and former American captain Dave Stockton saw Woods at Hazeltine and said he looked lean and fit, and ready to play. The quick withdrawal after committing to the tournament just a few days before was a surprise, Stockton says, especially given the vague references to discomfort with "off-speed" shots.

"He looked really good to me at the Ryder Cup, but he wasn't getting any reps in there," Stockton says. "If he had some kind of problem, I would have guessed it would be with the long game."

In a "standard" comeback from an injury, a player is usually able to chip and putt first, before graduating to full-speed swings, Stockton says. By that logic, short game and finesse shots should be the first things to get sharp.

"If you can go out and play soccer with your kids, you can practice short game. So it would be confusing to me if it was some basic issue with his short game," Stockton says. "If he did have some kind of problem, a good teacher would go down the list of what it could be in five minutes. It isn't complicated. Tiger is like Nicklaus in that he has everything worked out in his head ahead of time. He knows what he's doing or not doing, and he knows what to work on. The teacher's job is to make him feel comfortable."

Getty Images

But many people don't think Woods' comeback is exactly "standard." One look at the video from Woods' first few tournaments after his first back surgery shows some gruesome short-game shots -- ones Woods described as an isolated mechanical problem, or being "stuck between patterns." But experienced players and teachers say they recognized those shots as ones coming from a player who has the chipping yips, a potentially career-ending problem for a player who at his peak was the game's ultimate short-game wizard.

Golf Digest 50 Best Teacher Randy Smith has worked with dozens of PGA Tour players, including Justin Leonard, Harrison Frazar and Martin Flores, but his experience with the yips starts first-hand. He's had them in his own chipping game since 1976.

"When I heard Tiger say he wasn't ready after committing, the first thing I thought was that it has to be the chipping thing," says Smith, who is based at Royal Oaks Country Club in Dallas. "I've admired Tiger's short game up close ever since he was a junior player. And if he had his short game, he could go out in Napa and shoot 72-73 and say it was valuable to get out there and see what he needed to work on. But the one thing he can't handle is the physical embarrassment of double-chipping it or stabbing at it. He could take the embarrassment of hitting a snap hook out of bounds, or hitting a fat wedge and making a double bogey. The yip thing embarrasses you to your core as a tour player, because it makes you feel like you don't have control."

Bill Harmon has known Woods since the days Harmon's brother Butch was his coach. Harmon works with PGA Tour Champions player Jay Haas and has caddied for Haas at events like the Ryder Cup, where Woods was a fellow team member. Harmon has had his own struggles with pitching yips and says Woods probably knows that he can't compete with his short game the way it is.

"He had to have seen it at Hazeltine," says Harmon, who is based at Toscana Country Club in Indian Wells, Calif. "They were nipping pitch shots off that turf and bombing tee shots long and straight. They were playing golf the way he used to play it. It was probably a wake-up call that he wasn't close. I just wish he'd be honest about it. Have a press conference and spend 30 minutest telling people what's going on with your game. Some of this stuff that makes him so mad -- all the speculation -- he brings on himself by being so secretive."

2016 Getty Images

Whether it's the long-term issues with his driving or the potential flare up of the short game problems, Harmon says Woods has to rebuild his game from scratch -- a big ask for a 40-year-old with a long medical history and a giant competitive legacy to try to recapture.

"He's going to have to change gears, and that's something he hasn't been able to do. He's still talking about being explosive and all that," Harmon says. "This is the greatest player who ever lived. Somebody who won the British Open just hitting irons off the tee. What he's going through, you can't cure with the same old stuff. You have to change the system. The things that should be A-B-C are now a Rubik's Cube for him. Will he have the patience to do it? To put one block on top of the other? He's still Tiger Woods, but he has a long way to go."

The first step toward finding out just how long is actually playing an event.

"Until you get in the arena, you're not going to know what those vulnerabilities really are," Smith says."You need to get out there and try it, and give yourself something to take to the next tournament. Say he does have this yip issue. It'd be a shock to people and an embarrassment to him, but people would also see him as a human being. They'd see him as a guy having the same problem a lot of people have. They're going to identify with his struggle to get it back. And if he can develop a method that lets him work around it, he could give a lot of players hope that they can get back into the game they love. I'm rooting hard for him."

But the longer Woods' layoff goes, Norman says, the more likely it becomes that he won't come back at all.

"Your confidence can get down to a level where it's hard to get it back up," Norman says. "People expect you to hit it 300 yards as if nothing has changed, but your mind has changed."