News

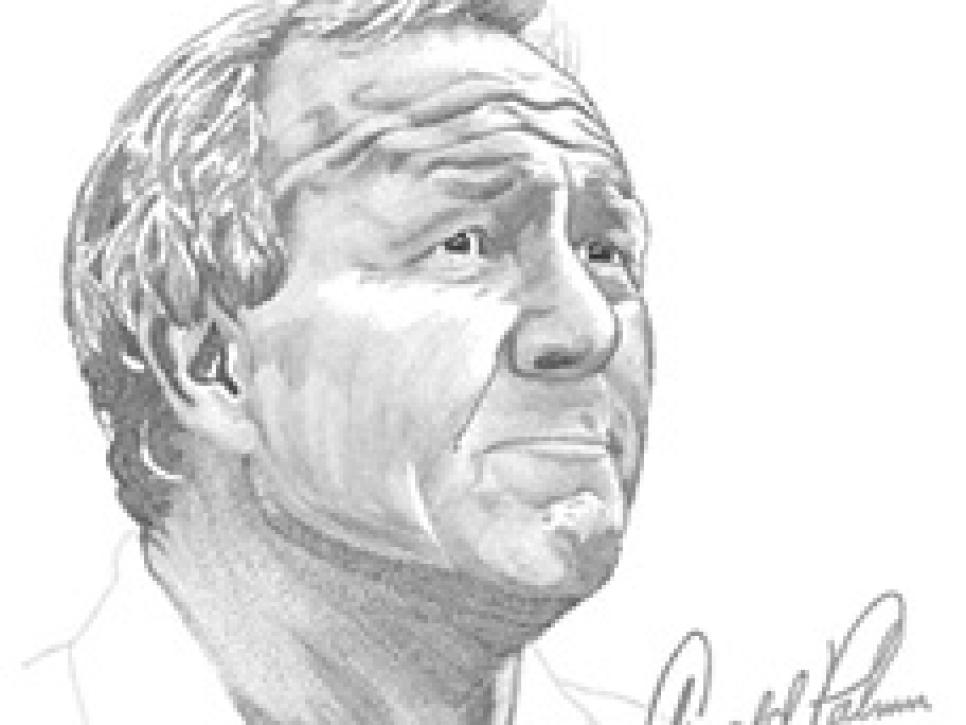

A portrait worthy of a King

Chase's 30-by-40-inch portrait consists of 22,719 tiny words and numbers.

The idea came to Jim Chase in his sleep.

He remembers waking his wife, Barbara, and saying, "I have a cool idea."

The idea, a portrait of Arnold Palmer.

The cool part, it would not be a traditional painting. He would do it in microscopic words and numbers. Every line in Palmer's handsome face, every furrow in his brow, every strand of hair, every shadow -- everything -- would be a name, quotation, description or golf score.

From two feet away the portrait would seem to be a conventional pen-on-paper stipple of Palmer circa 1970.

But up close the tiny words and numbers would be seen for what the artist wanted them to be: a story of Arnold Palmer's life.

"Honey, that sounds nice," the artist's wife said, turning back to sleep.

That night, late in 1988, with no way of knowing, James David Chase had announced an artist's obsession. In the end, he would create the Palmer portrait using 22,719 words and numbers. At eight words an hour, that's 2,840 hours. In work demanding control of fine muscles drawing lines as thin as one-tenth of an inch, Chase learned to make strokes between heartbeats. His estimate: 500,000 pen strokes.

He calls the portrait "Gratitude," symbolic of the sentiment that has flowed for decades between golf fans and Palmer. From wake-up to finish, Chase worked 15 years.

From first dynamiting to final polishing, Mount Rushmore took 14 years.

Chase was just another dogged victim of golf. His home course is thick with weeping willows, and "my game fits the 'weeping' part." As a professor of communications at Pacific Union College in Northern California, he paid little attention to Palmer's twilight years on the PGA Tour.

Still, for good reason, the idea was in his mind, waiting.

He became an artist as a child when he won a bicycle in a coloring contest sponsored by Cheerios. Fascinated by the improbable in the comic-book series, Ripley's Believe It or Not!, Chase admired heroes writ large: his grandfather the world-champion rifle shooter, astronauts on the moon, "men who did the impossible."

Among them, Arnold Daniel Palmer.

"On television every week," says Chase, a teenager in Palmer's best years, the late '50s and early '60s, "there was Arnie harvesting golf balls out of knee-high rough, leaning forward, pleading with the ball to do his bidding. On the greens, bringing his body into the form of a question mark, knocking in putts from everywhere. And such a wonderful smile and manner."

So, one night at home, Chase woke up knowing what he must do. He would combine pieces of his life that he loved: art, research, golf and a hero. On June 12, 1989, after six months of planning, he did the portrait's first sentence: "Marries Winnie Walzer in Dec. 20, 1954; he is a devoted family man." It's just above Arnie's right eye.

He worked in secret. He hid the 30-by-40-inch drawing board in his studio. He talked about it to no one but his wife, to whom he talked forever and to whom the portrait is dedicated.

"Only God and Barbara know the hundreds of hours I worked," says Chase, 61. "And I loved every minute."

On June 3, at its museum in Far Hills, N.J., the USGA will open the Arnold Palmer Center for Golf History. The centerpiece will be Chase's portrait. However grand that guarantee of immortality, for Chase it will rank second to an earlier moment.

On Nov. 25, 2003, the artist met the hero.

Chase knelt in front of Palmer's office desk to explain the portrait's genesis and intricacies.

On the portrait's chin are 143 names, including a woman of the club who paid the 8-year-old Arnold a nickel to hit her ball over Latrobe's sixth-hole ditch. Near his ears are words Palmer heard -- some from his mother. Near the lips, words he said -- some about his father. Near the eyes, things he saw -- the eyes themselves are one word repeated 40 times in the right, 46 in the left. The word is "Winnie." He loved her at first sight.

The artist spoke of all this, and the hero rose to look at the portrait, and in a whisper, slow, halting, Arnold Palmer said to Jim Chase, "That is the most amazing thing . . . I have ever seen . . . in my entire life."