The Loop

Music was Glenn Frey's profession, but golf was his passion

The Eagles’ Don Henley made it a habit of asking manager Irving Azoff why the band always stayed at hotels and resorts near golf courses. Azoff knew Henley knew the answer, as did everyone in the roadshow: Glenn Frey’s infatuation with the game.

“When the band got back together in ’94,” Azoff told me last week, “it kind of became booking our tours around where Glenn wanted to play golf.”

Frey’s death on Jan. 18 at age 67 meant more than just the passing of a legendary musician, singer and songwriter. From the 1990s into the 21st century, Frey was active in golf fundraisers nationwide and a regular in the two pro-ams that are mainstays of the PGA Tour’s West Coast swing. PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem noted Frey’s passing, and a flag hung at half-mast at Sunningdale Golf Club in England in Frey’s honor.

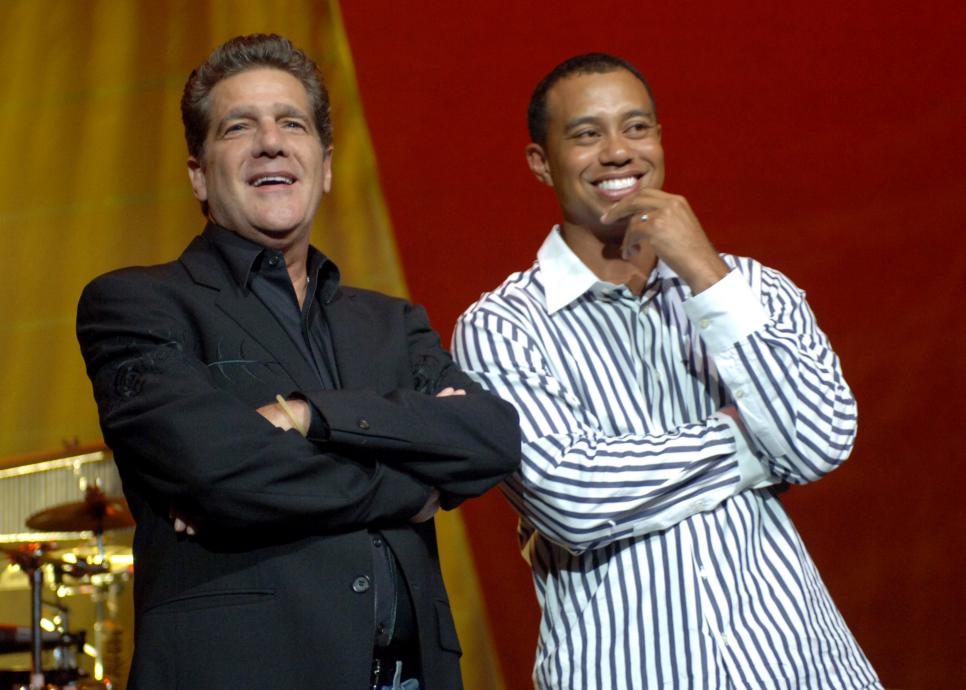

On Twitter, testimonials were posted by Cristie Kerr, Jason Gore, Rocco Mediate, Dottie Pepper (hash-tagging hers #Takeiteasy), John Daly and Pat Perez. Arnold Palmer talked about Frey from his office at Bay Hill, where a photo of the two of them hangs in the grillroom. Tiger Woods has memories of Frey performing in his “Tiger Jam” and “Block Party” concerts (below).

The timing of last week’s CareerBuilder Challenge was another reminder of Frey’s roots in golf. Frey had a home at PGA West, a membership at The Madison Club and played the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic six out of seven years from 1998 to 2004. He was even more of a fixture at the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am, playing with Craig Stadler for 12 years starting in 1996. Twice the pair finished second in the pro-am competition.

Long-time friend Peter Jacobsen, who for years partnered with Jack Lemmon at Pebble Beach, talked to me about the importance of elite celebrities playing in tour events—and Frey’s role in that. “We’re in a time when we don’t see that as much as we used to,” Jacobsen said. “Glenn was always in the forefront. Like Huey Lewis, he was always a willing participant.”

Brad Faxon and Billy Andrade befriended Frey by playing in the singer’s pro-am in Aspen, Colo. As a return favor, Frey provided entertainment at their charity event every summer in Rhode Island. “Glenn would always say, ‘Ever see me at the piano, I’ve had too much to drink,’ ” Faxon said. “Inevitably he’d be at the piano singing with Joe Pesci.”

Above the desk in Faxon’s office is a photograph of Frey as his caddie in overalls at the Masters Par-3 Contest. Faxon remembers asking Frey why he didn’t start playing golf until the 1990s. “I had to wait,” Frey joked, “until the clothes got better.”

Frey putted and played guitar right-handed, but was a lefty on the course. His handicap at Bel-Air Country Club in Los Angeles was 17, the byproduct of what Faxon described as “a slapper sort of slice” accentuated in later years by his chronic rheumatoid arthritis. Faxon called Frey’s short game “gritty.”

The best example was in 2002 at Pebble Beach, where Frey cut Stadler 31 shots over 72 holes to earn him the inaugural Jack Lemmon Award as the amateur who helped his pro the most.

For Frey, all the Grammys and sold-out stadiums didn’t compare to the rush of standing on the 18th tee at Pebble tied for the lead. As he told the Monterey Herald: “What could be better than that?”

Editor's Note: This story originally appeared in the Jan. 25 issue of Golf World.