News

Tailing Tiger at Augusta

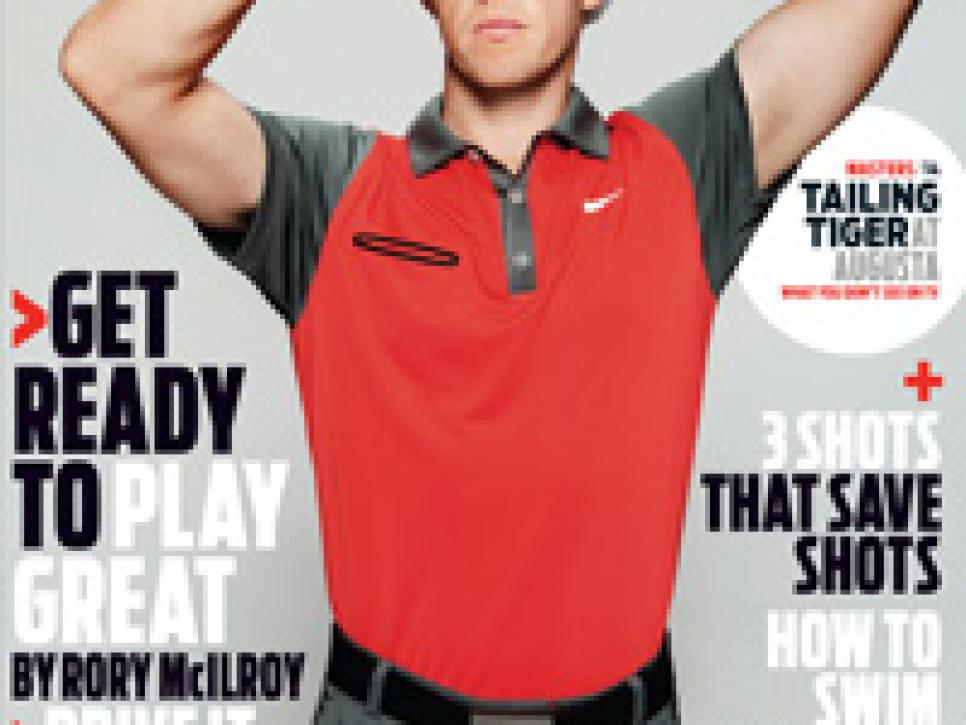

This is about stalking Tiger Woods at the Masters. Assuming little new would be learned from sitting in on the man's 19th year of press conferences at Augusta National, I used my media credential to launch a low-level surveillance operation. For seven days, from the moment Tiger Woods arrived on the clubhouse grounds until the moment he left, I tailed him. Call this questionable, if not creepy, behavior. But I'll bet you're curious to know how it went.

The first problem of any stakeout is finding the right spot. Not wanting to risk lifetime banishment, I don't ask if Augusta National prefers fixed or self-climbing tree stands. The second-best post for hunting Tiger, I find, is a wooden bench beneath a hanging flowerpot on the front veranda of the clubhouse.

The front of the clubhouse is very much the back of the tournament. The hubbub is on the other side, with outside dining and golf masters being interviewed under the big oak as they come off the 18th. It's also under this oak that masters of a different kind—of companies, networks and markets—engage in the initial chitchat that ultimately leads to how the universe is run. This isn't where you catch Tiger. "Hot-foots" scarcely describes how he navigates this part of the property.

The champions' parking lot is the place for Tiger's unguarded moments. It's a pitch shot from the wooden bench, where I sit with the Augusta Chronicle on my lap as if peace and quiet are all I require at a world sporting event. And because it's Georgia, passersby, mostly members and their guests dressed as if for church, offer warm smiles instead of dirty looks even though they know I'm loitering.

One by one, Mercedes GL450 4Matics emerge from the shaded driveway known as Magnolia Lane, noiseless and identical, like giant silver beetles. The curved shell and sleek antennae of these SUVs, too, suggest something like evolutionary perfection. That every contestant at the Masters is given the same vehicle is one of many details that make this tournament unique. A small numbered decal on the rear window supplies the only means of differentiation other than the license plate. At a regular tour event, a sponsor might extend courtesy cars to players in a variety of colors, models and makes, with qualifiers and players of lower status perhaps having to obtain their own wheels. It's hard enough for a player to find his car at Augusta; how am I ever going to find Tiger's?

Despite the anonymity of the tinted windows, you learn to sense the operator. Halting and uncertain, rookies overdo the brakes. Veterans whip through the champions' lot, not as a shortcut, but to taste what's possible before continuing on to the lot behind the range. Before they make the roundabout—where patrons endlessly queue to snap photos of themselves tending the flagstick propped in the flower bed shaped like the United States—you can often guess a past champion just by the steady, even speed.

But then... a black one! A Mercedes GL550 with thin tires, badass rims and a layer of dust along the underbelly, claiming its spot in a sea of silver. The driver is bang on two hours before his tee time, just as he'll be all week. The only exception will be Saturday, when he rolls up hot and bothered really early, keeps it idling as a security guard hops in, then returns before speeding off. Some meeting with the tournament committee about a drop and a possible rules violation.

AP Photo/Gregg Forwerck

BRINGING A PIECE OF HOME ON THE ROAD

Tiger Woods flew in on his jet from Jupiter, Fla., but he had his car driven the 534 miles to Augusta. "It's not a normal week, but he tries his best to make it a normal week," says Glenn Greenspan, Tiger's publicist. Tiger's mother, Tida, will drive the silver loaner. I tell Greenspan this will make my job easier, and he laughs nervously, uncertain about my mission for the week, of which I've just briefed him.

Caddie Joe LaCava gets out of the passenger side. Tiger, dressed impeccably with his golf shoes already on, pops the remote, and there in the trunk lies his bag, alone on its belly. Instead of four guards in the lot, one at each corner, there are now eight. Mark Steinberg, Tiger's agent, and Chris Hubman, Tiger's CFO, materialize. Both are physically fit, goateed men in Nike shirts with dark crew cuts, and so almost indistinguishable.

Tiger dillydallies. The zippers of his golf bag, the car door, his iPhone. But then, before you know it, everything is in place, and he's moving fast. In tight formation, three guards, Greenspan and Steinberg tail him to the clubhouse. Oddly, these five men are jogging as Woods walks, but they gain no ground. Once inside, Tiger ascends the narrow spiral stairway to the Champions Locker Room solo, taking the steps three at a time. Amazingly, there's no sense of hurriedness. With stealth and familiarity of the terrain, he moves like, well, a tiger.

THE SANCTUARY

The Champions Locker Room is a modest space with three card tables, three walls of shared mahogany lockers, and a display case devoted to the defending champion. Tiger's locker is on the left, which his locker mate, Jackie Burke Jr., presumably hasn't used much since last competing 40 years ago. Tiger often eats lunch here. It's his sanctuary.

Twenty minutes later, Tiger descends, taking the steps singly. You think about the surgeries to that left knee, how the slabs of surrounding muscle undoubtedly protect some motions and not others, and you venture Tiger is thinking the same thing.

The shuttle to the range is, of course, a highly coordinated event. Tiger rides shotgun in a four-seat cart operated by a mop-haired teenager who proceeds like it's his driving test. The burly guard on the rear seat, Tyrone Croske, has been with Tiger for every Masters he has played. Croske used to blend in with street clothes, but three years ago he switched to the black-and-white uniform of Securitas, the firm that runs security at the Masters. On a trailing four-seat cart, an equally timorous teenage girl escorts LaCava, the clubs and two more guards. For comparison's sake, minutes earlier Luke Donald was shuttled four strong—chauffeur, caddie, clubs, his own person—on a two-seat cart, unguarded.

The difference with Tiger? "He's a magnet for attention, so if something weird is going to happen, it's probably going to happen to him," says another guard on Tiger detail.

AP Photo/David J. Phillip

As fast as the fairway crosswalk ropes open and close, word has spread over club grounds: "He's on the driving range!" The number of spectators in the practice area triples. Children are ushered to the rope, shorter spouses step in front of taller ones, roast-beef-faced old men squint, and bachelors with full beers flex onto their tiptoes. The merchandise center actually structures its restocking and employee-break schedules around Tiger. "When Tiger's on the course, it's dead, but when he makes the turn or leaves for the day, it gets real busy," says one employee who has worked at the merchandise center for more than a decade.

As the gallery compresses and bodies jostle, much muttering begins. Each comment is anonymous, because to scan for the source is to risk toppling over.

"There he is."

"Man, is he ripped."

"He didn't even look at my kid."

"What's the big deal? Not like he's going to turn water into wine."

The last only underscores what this really is: a communal religious experience. There he is.

ALONE IN A CROWD

One thing you get from tracking Tiger for seven days, as opposed to one or two, is his unwavering warm-up routine (see story).

To close today's putting session, a feat that incites a fervid reaction: Cradling a ball in his putter well, Tiger suddenly and violently windmills the club over his head like a cricket bowler. In a miracle of centripetal force, the ball stays in the well instead of rocketing out and striking someone in the face. Tiger casually picks the ball out without so much as a smirk, then walks to the chipping area.

At the range, players pause to watch him. A few notable souls, like former coach Butch Harmon and former caddie Steve Williams, get not the slightest recognition from Tiger as they walk by. "I talked to him only once today, to make sure we weren't going to wear the same shirt," says Tiger's teacher, Sean Foley (yesterday had been a gaffe in Nike peach), whose absence from the practice tee is conspicuous. But Foley knows when not to mettle. Today, he loves Tiger's "slight pause at the top and how the downswing starts from a turn of the hips rather than a lunge of the shoulders." Foley's too cerebral a cat to ever be described as giddy, but his student is thumping the club into the earth like a Formula 1 piston, and Foley's talkative.

Foley is interested in parasympathetic states, or the complementary conditions of the nervous system that signal a body to either digest and rest, or feed and breed. The effects of these rhythms on our golf performance can be huge, but Foley believes through technical breathing and stretching they can be harnessed. After I shamelessly pitch some bad chat about my struggling game, Foley leaves me with a quote from Deepak Chopra.

"Every single one of us is doing the absolute best we can given our state of consciousness."

FIVE MINUTES OF SOLITUDE

Is it punkish the way Tiger waits, palm open, not even looking at LaCava, to be tossed each range ball? As it is, the way he's striping his driver justifies any parasympathetic state, or lack thereof. Every shot is a climbing bullet, curving into and surfing the breeze just as intended. Tiger smiles. An hour and a half on club grounds, and he finally smiles.

Leaving the range, he signs autographs for 47 seconds, which is 47 more than will occur after "DropGate." The security convoy reassembles, and plays in reverse back to the Champions Locker Room. Tiger never misses this five-minute dose of solitude before facing the throng at the big oak and the first tee.

Note: The most poignant autograph Tiger signs all week is for a fellow-competitor. After their practice round together, Guan Tianlang needs to shower and quickly dress for the Amateurs' Dinner. The 14-year-old looks on shyly as Tiger putts, but the four-time champion gives no indication he'll be anything other than the last man practicing as dusk settles. It takes Tianlang 10 minutes to gather the courage to approach, clutching his hat and magic marker.

"Yeah, sure, bud," Tiger says, then signs the boy's hat to a full round of applause.

Photos (from left): Dom Furore, Donald Miralle

Tiger avoids eye contact as if he fears interacting with other humans might drain his focus. The rigidness only breaks around his older pals Mark O'Meara and Fred Couples, and young golfers. When Tiger makes room in chipping areas during a practice round with T.J. Vogel, the 2012 U.S. Amateur Public Links champ, the impression is of a cub being taught. Vogel describes the experience as "like playing in a video game."

Tiger's competitive rounds are the record of TV. When the infamous wedge shot strikes the flag at the 15th and ricochets into the water, my memory is of Steinberg turning and doubling over like he'd been kicked below the belt. No one in the gallery could miss the entourage on Sunday, all dressed in red and black, which includes Lindsey Vonn hobbling in a knee brace and short shorts, and Tida being escorted by Phil Knight, chairman of Nike. No, the enlightening moment of the week comes after Tiger is through playing golf.

As Adam Scott lines up a birdie putt on the 72nd green with Angel Cabrera watching from the fairway, I'm not among the patrons clutching umbrellas. Nor am I among the members and players pressing around various TV screens in the clubhouse. For the playoff under that thunderous sky, I'm at my wooden bench. I see Tiger Woods, carrying two plastic bags and a box, descend the exterior side stairs alone. The death stare has been supplanted by a faint, placid smile. Warmly, he says goodbye to a group of security guards and drives off in his car, 15 minutes before the tournament ends. He wasn't going to win, and that was all he needed to know.

I don't think he noticed me.

Photo: J.D. Cuban

.jpg)