News

Ryder Cup 2018: Spain is the best country in Ryder Cup history, and Europe needs them more than ever

Before we can talk about Spanish dominance at the Ryder Cup, we have to talk about America. If you’ve only been following golf’s foremost biannual exhibition for the last 30 years or so, you might assume that the U.S. has a pretty poor lifetime record. After all, the Euros have been eating our lunch with very few exceptions since 1985. Yet the history of this event stretches back to the early days of the 20th century, when Team Europe was just Team Great Britain, and Team Great Britain was frankly awful. Ireland was added to the mix in 1973, but that made no difference (more on Irish futility in a moment). In the 50 years between 1927 to 1977, Team USA posted an astounding 19-3 record. Even with the recent European surge, the all-time American record is still extremely good at 27-14. Put another way: for Europe to draw even, their team would have to go undefeated from now until 2044.

Let’s draw it out a bit more. In the history of the Ryder Cup, American players have a record of 695 wins, 547 losses and 200 draws. That’s good for a 55.13 percent winning rate, and based on the years and decades of endless victory, you’d have to assume no other country could come close to matching them.

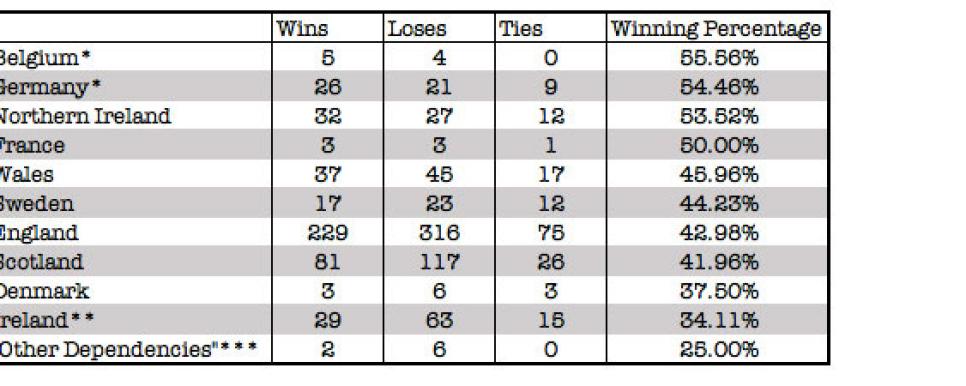

You’d almost be right. Here’s how all but one of the contenders stack up, listed from best to worst with records and winning percentages:

*Both Belgium and Germany have featured only two players each in Ryder Cup history.

**Ireland is extremely bad at the Ryder Cup. The country has put 11 golfers onto the team, and not a single one has a winning record.

***Guernsey, Jersey. These are basically England.

(One more note on the numbers: In the Ryder Cup, matches overlap. If two players are partners in foursomes, for instance, they’ll each get credited with a win, though it only contributes one point to the team. Because these partnerships are not neatly divided by country, though, the best way to measure national success is still the accumulation of individual records.)

As you see, Belgium, which has been lucky with a very small sample size, is the only country that could squeak by the U.S. That list omits just one country, and that country stands above the pack.

Hold on to your peinetas:

SPAIN: 77-54-26 (57.32 percent)

Analysis: That’s really, really, really good.

Ten Spanish golfers have played in Ryder Cup matches (one other, Miguel Angel Martin, made the team in 1997 but was controversially removed by Seve Ballesteros), and those 10 have posted almost as many points as Scotland’s 22 historical players, and more than doubled the output of Ireland’s 11. They are the only country in the world besides Belgium (again, huge asterisk there) with a better collective individual record than America. And when you consider that all of their players have played in the post-1979 European era, it’s no stretch to say that their success has been the most critical factor in curtailing U.S. dominance. When it comes the changing of the guard that took place beginning in 1985, the rest of the continent owes an enormous debt of gratitude to the Spanish. They are American killers.

Tim Matthews

The anecdotal evidence backs up this conclusion. When the Europeans finally won in 1985, three of the top five performers, including the top two, were Spanish. In 1987’s 15-13 win, Ballesteros led the way with four points, and Jose Maria Olazabal was not far behind with three. And when Europe retained the Cup in a dramatic 14-14 result in 1989, it was Olazabal pulling down 4½ points to lead Europe, with Ballesteros in second at 3½.

Let’s put a very fine point on it, shall we? Without the Spanish, Europe would not have won a Ryder Cup until the 1990s.

And now we have to address the fundamental question: Why are the Spanish so good?

Someone with a mystic bent might theorize that there’s something special about the Spanish competitive spirit and pride of place that gives them a psychological edge in the Ryder Cup. There’s no way to substantiate this idea, and it might veer uncomfortably close to stereotyping, but we can look at other sports to see if the success carries over.

Spain has been quite successful in men’s tennis, accumulating the third-most grand slam titles in the Open era (after the U.S. and Sweden), but though there were a string of good clay-court players preceding Rafa Nadal, the king of clay accounts for most of that hardware. (The women have not been quite as spectacular.) In soccer, the Spanish were actually one of the biggest underachievers in Europe before their breakthrough from 2008 to 2012 in two Euro Cups and one World Cup, so there is no longstanding tradition of team success on the international stage. And going back to golf, Ballesteros has been the only Spanish golfer with a truly spectacular career in the majors. He won five times, while Olazabal won twice and Sergio Garcia corrected a lifetime of near-misses in the 2017 Masters. None of this provides much insight for their Ryder Cup strength.

If you take the simplistic view, you might conclude that Spain has just been lucky to field three extremely successful Ryder Cup golfers, from Seve (20-12-5) to Jose (18-8-5) to Sergio (19-11-7). That trio accounts for the vast majority of Spain’s wins, but neat as this narrative might be, it doesn’t tell the whole story. It doesn’t tell how Manuel Pinero posted a 6-3 record in three Ryder Cups and led off the Sunday singles in 1985 with a tone-setting 3-and-1 win over Lanny Wadkins, or how Jose Maria Canizares finished with a winning record in the neck-and-neck ‘80s and won the final critical point for Europe in the 1989 draw, or how Rafa Cabrera-Bello was the only European to descend into the hell that was Hazeltine National in 2016 and emerge without a loss. (By the way, add this to the reasons why Thomas Bjorn was a fool not to pick him for this year’s team.) It doesn’t tell how even beyond the big three, a Spaniard has been close to the beating heart of Team Europe in every Ryder Cup since 1979.

Whatever the reason, Spain has produced an unending string of Ryder Cup heroes and distinguished itself as the event’s most successful country. And even if we don’t know the magic formula behind the glory, we do know that for Europe to have a chance in Paris next weekend, the Spanish must deliver again. This time, the nation arguably has its weakest representation yet in an off-form Garcia and the untested rookie Jon Rahm, he of the questionable temperament and spotty record in majors. But don’t let the appearance of weakness fool you—the Spanish lion is dangerous even when wounded, and there is no prey it likes better than the lonely American.

.jpg)