Courses

Is This The Time To Join A Private Club?

As golf hotbeds go, Kutztown, Pa., is a long way from, say, Carmel, Calif. In 2008, however, the Pennsylvania borough finds itself at the core of a phenomenon that's sweeping through American golf: the changing face of the private club.

The numbers are startling. According to the National Golf Foundation, in 1970 there were 10,188 golf facilities in the United States. Private clubs accounted for 45 percent of the total. By 1990 the share of private clubs had slipped to 37 percent, and today such clubs represent only 28 percent of all American golf facilities.

It's not only the percentage of private clubs that's dropping. The raw number of private golf clubs in the United States actually decreased by 395 between 1990 and 2007, to 4,415. This while the number of daily-fee and municipal courses rose by 3,519 facilities, to 11,555. Project these statistics against a background of softening participation in the sport--the number of golfers playing eight or more rounds per year fell 13 percent between 2000 and 2007--and you have a game in transition.

"We're facing a new concept of the private golf club," says Mike Hughes, CEO of the National Golf Course Owners Association. "With the exception of the old-line private clubs--and I would say that's a very small slice, maybe one-tenth of all private clubs--everybody else is in the new reality."

Golf in America, though overwhelmingly a public enterprise (only 9 percent of all U.S. golfers are private-club members), has long been perceived as exclusionary. The truth is, it's easier now than at any time in the past 20 years to join your local private club (assuming you don't live in Pine Valley, N.J., or Augusta, Ga.). Likewise, if you prefer your golf public, the selection and affordability has never been more tempting.

The underlying reasons for golf's equivalent of the summer clearance sale span the American cultural spectrum from the graying of the baby boomer to the prevalence of the two-income family; from lousy club governance to emerging parental trends and from some place called Chambers Bay to the preferences of Generations X and Y. But industry insiders agree on four inextricably linked forces: the economy, heightened competition, the baby boomer and club governance.

Take Kutztown. If there is a place that represents the pressures facing the private golf club in America, it's Kutztown's Berkleigh Country Club. "The Berkleigh" was founded in 1925. In that era, Jews, much like the Irish and Italians in the region between Allentown and Reading, weren't welcome at the more established clubs. Berkleigh became an idyllic refuge.

The club was at its best in the 1970s, just as Adam Leifer (who would win eight club championships) and his pals, including future Golf Channel personality Rich Lerner (a two-time Berkleigh club champ), headed off to college. Better jobs awaited their generation in places like New York, Boston and Chicago, and the unraveling of Berkleigh began.

Because of the club's location, about 20 miles outside Reading, the lunch crowd started to dwindle, and the membership began to migrate to Berkshire Country Club, which is only five minutes from town. Soon, the time pressures felt by the remaining dual-income baby boomers and their resulting socialization patterns began to affect club life. Soccer practice and T-ball called; gone were the days when guys would stick around after 18 holes and have a few beers. Even on weekends, members began to forgo lunch. "They'd finish 18, get in the car and go home," says Leifer.

As if the attack from within wasn't enough, outside competition arose from half a dozen nearby public courses like the semiprivate Golden Oaks Golf Club in Fleetwood and Reading Country Club, a noted old-line club (where Byron Nelson once served as the golf professional) that is now open to the public.

As the social and economic hurdles to membership at more prestigious clubs, such as nearby Saucon Valley Country Club, began to recede, Jewish clubs such as Berkleigh found less purpose and fewer members. The club's days were numbered.

Lerner, who lives in the Orlando area, visited the club in July 2007. "We jokingly billed our get-together as The Finale," he says. "In your mind you say it, but you don't believe it's going to happen. You hold out hope."

Three months later, Berkleigh was shuttered and sold to a local cement company. Everything in the clubhouse, from sofas to deep fryers, was auctioned off. The club-championship plaque, with the gilded names of proud victors past, now hangs not in a chatter-filled grillroom or a grand dining room, but in Adam Leifer's cellar. In April, Berkleigh Golf Club reopened as a public course with a $60 green fee that includes a cart.

Regardless of location, virtually all golf facilities--private and public--are confronting a common economic problem: too many golf courses. Some point a finger at the National Golf Foundation, the clearinghouse for golf-industry research and consulting services. The NGF got developers' attention in the late 1980s and early '90s by suggesting that, based upon participation rates that were climbing 3 to 4 percent a year and assumptions that aging baby boomers would soon retire--or at the very least work fewer hours--the golf-course market could absorb roughly one new course a day from 1988-'98. Partly as a result of that projection and partly as a result of anemic due diligence by developers and lenders, the American golf market went from 104 golf-course openings (public and private) in 1983 to 358 openings in 1993.

Today, NGF chief executive Joe Beditz acknowledges the golf-course glut but says that course developers heard from the NGF only what they wanted to hear.

"We said in 1988, that given the growth rates and participation rates we were seeing, golf could support it," Beditz says of the course-a-day plan. "We also said that the building should be across all categories, ranging from the low end to the high end. Of course, everybody not only built high-end, but they built in the same markets."

By 1999, the golf-course market began to turtle. As it turned out, golfers entering their mid-50s were working more hours and working later into their lives than originally expected. The supply of golf courses was outpacing demand, creating what amounts to a national golf bazaar. Jim Cook, chairman of the past-presidents committee of the Rochester (N.Y.) District Golf Association, sums up the situation succinctly: "There are too many golf courses and not enough players. We have so many really good golf courses that are virtually giving away their golf."

If you can forget for a moment the financial troubles this has caused countless facilities, and the fact that the course where you play might not be there in two or three years, the facilities' pain is the shopping golfer's gain. In New Hampshire, private clubs have taken to the state golf association's website (nhgolf.com) to troll for private-club members. In the East Bay region of San Francisco, a 40-year-old golfer who has been club shopping says eight private clubs within a 25-mile radius are aggressively dealing for his business.

Emerald Dunes Golf Club in West Palm Beach is competing in one of the most cutthroat geographic markets in the game. With an initiation fee of $150,000 and 150 members short of its goal, the club has established a "junior membership" that requires an initial payment of $35,000 and the signing of a five-year note at 5 percent for the balance. Recognizing the pressures on the club market is Frank Chirkinian, the former CBS Sports executive who led a purchase of the club in 2005. "You've got to be creative," says Chirkinian. "You can't just say, 'This is the price.' That's not going to work anymore."

Some of the most prestigious clubs in the country have come up with ways to keep the rolls full and the revenue flowing. Inverness Club in Toledo, Ohio, has been the site of six USGA championships and two PGA Championships. "I have friends and colleagues all across the country involved in private clubs, and to a person they're struggling with the same issues," says Inverness president Jim Schwarzkopf.

Inverness now offers one of the best nonresident deals in all of golf. Historically, Inverness has offered a handful of nonresident memberships. In recent years, however, the club has found opportunity in what it refers to as "regional" and "national" memberships. The initiation fee for a regional member (who must live 45 to 100 miles from the club) is $9,000. Annual dues are $4,200, and there is no food minimum. National members (100-plus miles from the club) pay an initiation fee of $6,500 and annual dues of $3,480. Each classification has full use of the club and the ability to entertain seven guests daily.

In golf-crazed Rochester, N.Y., the Country Club of Rochester, Monroe Golf Club and even vaunted Oak Hill Country Club now allow Monday outings. One longtime Oak Hill member confides that admission to the club has also become less selective. "Few would ever articulate it," he says, "but Oak Hill has lowered its standards to maintain its membership roster. Years ago it took one or two members to say no to an applicant. Today, that's no longer the case. People are getting in because they can write the check."

If the front door is open, the back door is busy as well. As private-club golfers compare their costs per round (including initiation fees, dues, monthly minimums, etc.) to the cost per round at the nearby upscale daily-fee, many are opting out of the hallowed halls. One of the departed is Ed Tills, 50, who dropped his Oak Hill membership in 2003 to join a local start-up club, The Belfrey International. The new venture folded in 2005, and though Tills might have rejoined Oak Hill, he found numerous advantages to remaining a free agent, cost and variety among them.

If the temperature ticks above 40 degrees, you'll find many of Rochester's private-club refugees teeing it up at Ravenwood Golf Club, where green fees range from $35 on a spring weekday to $72 on a summer weekend. The upscale daily-fee, which has a highly praised Robin Nelson design, completed its first full season in 2003. According to general manager Mike Roeder, the facility offers a seasonal membership, which numbered about 80 people last season. Just about every one of those players, says Roeder, migrated from a private club. "They play here once or twice a week and tell us, 'I don't know what I was thinking paying a $25,000 initiation and $350-a-month dues.' " Adds Roeder, "Rochester is a player's paradise right now."

The Baby Boomers

The oldest of the 77 million baby boomers (people born from 1946-'64) are now in their early 60s, and with annual buying power estimated at $1 trillion to $2 trillion they are the dominant force in today's private-club economy. One increasingly influential component of the boomer generation is its empowered women. "Women's earning capacity has risen over the years," says Susanne Wegryzn, the president and chief executive of the National Club Association, "and when you combine that with life-expectancy rates, in which women typically outlive men, we're going to see the women--through both income and inheritance--wielding a lot of influence in the marketplace. That's going to be a big factor."

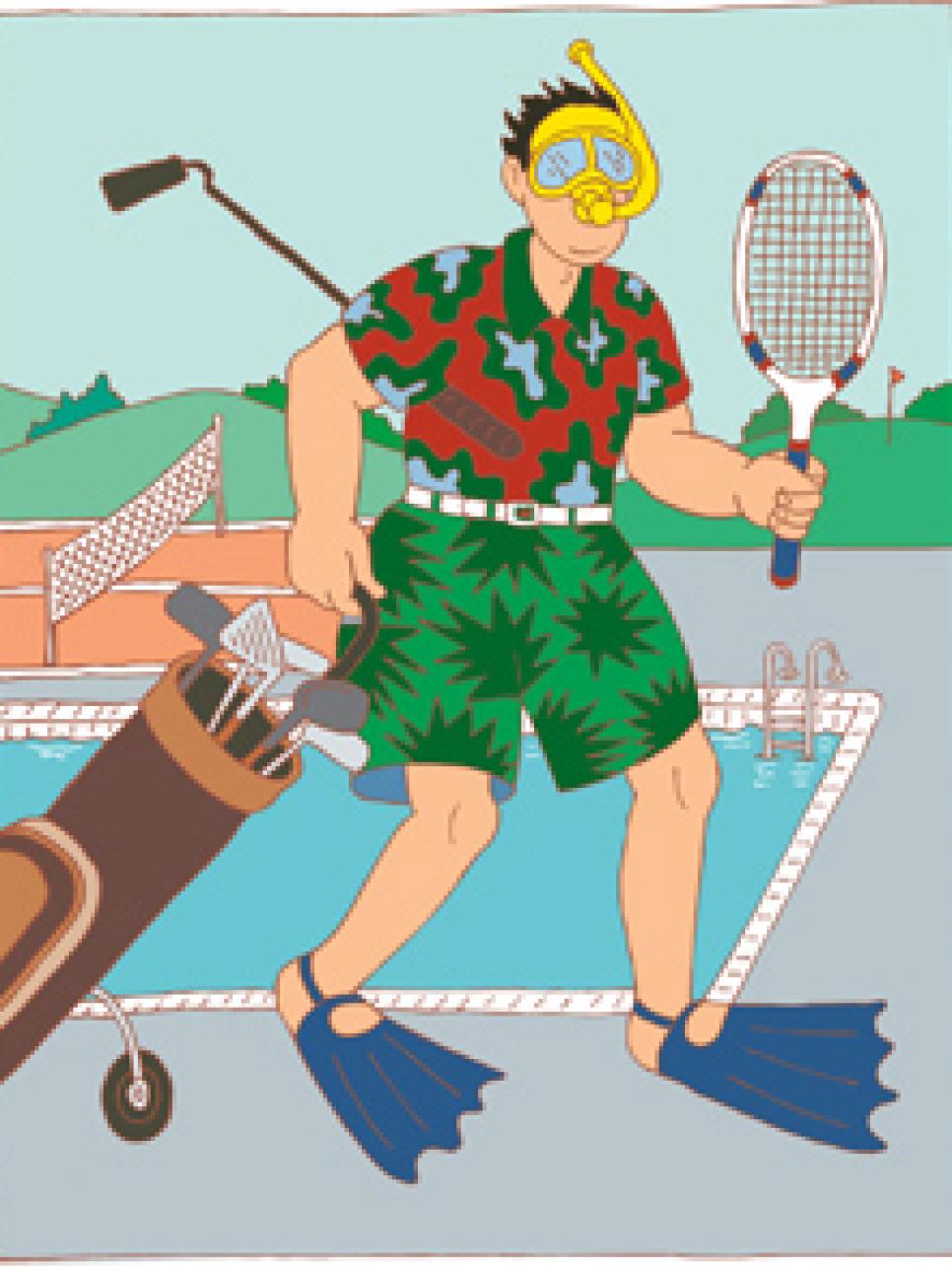

Boomers' impact on private clubs is already visible in the renewed emphasis on fitness programs and spa facilities. Wegryzn, fresh from the 2008 Golf Industry Show in Orlando, says, "Everybody we talked to is either expanding or adding one." The craze, she says, which has spawned the installation of everything from simple weight rooms to all-out spas, is fueled as much by performance as by vanity. "It's not just because boomers want to look good or age more gracefully," she says. "Boomers are looking for programs that will help them not only with their overall health but with their golf or tennis or squash game." Boomers are also focusing heavily on family. Private clubs report exploding demand from boomer-age members and prospective members for family-friendly activities. There was a time when the private golf club was the domain of the golf-loving male, but just as members are now under pressure to justify the costs of membership, so are clubs under pressure to become integral to the lives of the entire family.

Troon Golf is the largest golf-club management company in the United States. The Scottsdale firm manages approximately 200 facilities, 50 of which are private clubs. Founder and CEO Dana Garmany has been tracking these trends for years. "The private-club business has been 95 percent family in the last three years," says Garmany. "The guy might want to play golf, but he's asking, 'What can my kids do? How do they benefit? What about my wife?' The clubs have no choice but to adapt."

Olympia Fields Country Club outside Chicago has adapted. The club had just been the host of its fifth major championship, the 2003 U.S. Open, when the board decided to take a hard look at its future. The ensuing long-term study dictated that "family" would be the focal point of the club's planning. Not long afterward, says general manager Russell Ruscigno, 80 percent of the membership approved a $5-million dual-pool facility with a cabana, snack bar and a new tennis facility with Har-Tru courts; this in addition to the recently completed Steve Smyers renovation of the club's South Course.

The families that are driving these decisions include the children and grandchildren of boomers, Generations X and Y, yet it is among these young people that the challenges for private clubs have become particularly acute. In fact, Garmany and others in the industry believe that boomers and their families represent more than a programming or economic challenge. There's a sociological rub as well. Graying hippies--people who came of age in an era of establishment-bashing--and their progeny are showing more than a little apprehension at the prospect of being identified with a private club. Garmany tells of one private club where several newly admitted members age 45 and younger have requested that their names not be published in the membership directory. "They want to use the club," he says, "but they don't want to be listed."

With so much money at stake, and a tenuous grip on the coming generations, private clubs are realizing that they are no longer the only game in town. "It's very likely there is a better public course nearby. There are better restaurants on every corner. Poor governance and non-deductibility [of dues] have hurt," says Garmany. "There's a whole new way of thinking from the baby boomer, and there's also an element of political correctness that has caused people to rethink private-club membership. All these together have combined to create the perfect storm."

__ Club Governance__

Dr. Jeff Ausen confronted these challenges in 2006, when he was serving as president of Merrill Hills Country Club in Waukesha, Wis. The schizophrenic Wisconsin golf market, notable for its short season and avid-player base, had seen an influx of high-end public courses throughout the preceding 15 years. The competition had depleted private-club enrollments. Combine those trends with the aging of Merrill Hills' membership and the evolving lifestyles of its prospective boomer-age members, and Ausen came to a Catch-22 realization.

"On weekends our members' kids are playing soccer and baseball and football. On Thursday afternoons we used to have 60 or 70 guys playing golf; now we had 20. In our weekend events we'd have 120 people for a scramble or a best-ball, and now we were lucky to have 60."

Ausen, a longtime scratch player, hailed from the old school, approaching club life with a golf-first bias. "I always thought all we needed was a golf course," says the man who paid $1,500 to join the club 30 years ago and found himself asking new members to pay $20,000 and up. But after examining the financial and recruitment issues, Ausen did a philosophical 180. The guy who could barely recall dipping as much as his big toe in the Merrill Hills pool backed a new pool and tennis courts, amenities that would be paid for by an assessment. Members were stunned. Some were outraged, but Ausen was unfazed. "It put us in line with what people wanted," he said. "The days when there were a lot of golfers and a few courses and people would pay for only golf are over."

Though many clubs are confronting similar challenges, few have presidents or boards with Ausen's vision. Even if they do, club-governor turnover is frequent. In the biennial churn, clubs--their members, their facilities, their employees, vendors, budgets and strategies--get jerked around. Incoming governors, many of whom have no management experience, typically repeat the errors of their inexperienced predecessors.

This governance gap has created a market for contractors and vendors who have built entire businesses on exploiting it. Mike Young, a golf-course architect in Athens, Ga., has observed the spendthrift ways of boards for years.

"If I'm designing for an independent developer or owner," says Young, "he knows going in exactly what the work he wants done is going to cost, whether it's $5 million to build a golf course or $30,000 to re-do a green. Boards, on the other hand, have their own in-house 'expert' who is determined to spend more than the club down the street did. I've actually lost out on private-club projects in which I added a 30 percent markup. I lost because I was too cheap."

Fred Laughlin, who has long consulted with nonprofit groups on management issues, has recently begun working with the Club Managers Association of America on governance modeling for private clubs. His initial impressions of American private-club management and governance were not good. "Just awful," he says. "Mired barely in the 20th century." (See accompanying story by Davis Sezna.) How did we get here? Many of these clubs started because founders wanted to get together with friends. After a while the founders turned over management to boards, which in turn appointed presidents, who eventually hired GMs. "This happened over decades," says Laughlin. "Now we've got to a point where people are asking, 'Who's in charge?' "

It doesn't take a CFO to realize that there's something unsustainable about a 90,000-square-foot clubhouse in an age of dwindling enrollments. "A club needs to be run like a business," says Laughlin, adding that the top private clubs would rank among the top-10 percent of all businesses in the United States. Business-like thinking should extend, he says, to governance. "Who in their right mind would invest $50,000 in an organization that changes its CEO every year? Yet that's exactly what these members are doing and what these clubs are asking them to do."

As for Merrill Hills, in 2006 the club had one new member and normal attrition of 13 or 14 members. In 2007, as expected, about 35 members left the club because of Ausen's assessments. Even with that exodus, the enrollment is down only about 10 spots or so. Usage patterns and revenue will be the ultimate judges, but, says Ausen, "At least we have a plan. We now have something to offer in addition to a beautiful golf course."